Chapter 3: The viewfinder—transparency and voyeurism from Albrecht Dürer to Ai Weiwei

08 Oct 2020

- Keywords

- Art

- Arts and Culture

- Essays

Every representational image ever made is necessarily a finite framing of the outside world, a viewfinder presenting only what the creator wants us to see. This finite point of view is configured inside of the boundary or the limits of the frame, suggesting a specific spectator-object relationship in front and behind the picture place, as well as the possibility of a partially or entirely fictional construct within this restricted gaze. Leon Battista Alberti’s early treatise on painting and perspective, De Pictura (or Della Pittura) of 1435 described how artists of the 15th century were attempting to go beyond their mediaeval forebears to better model and render visible objects as if in three dimensions, rather than employing flat and symbolic stand-ins: “First of all, on the surface which I am going to paint, I draw a rectangle of whatever size I want, which I regard as an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen” (Alberti, 1435/1972, pp.54-55). These passages describing the means to achieve perspectival accuracy in turn led to various technical instruments to aid in this new era of realistic drawing, one of which was dubbed ‘Alberti’s Frame’.

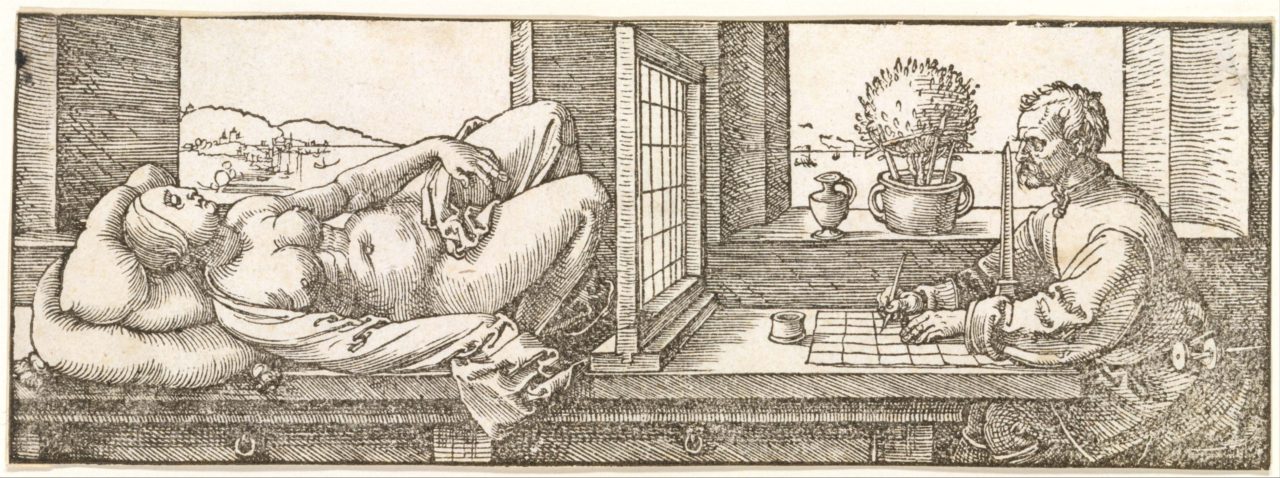

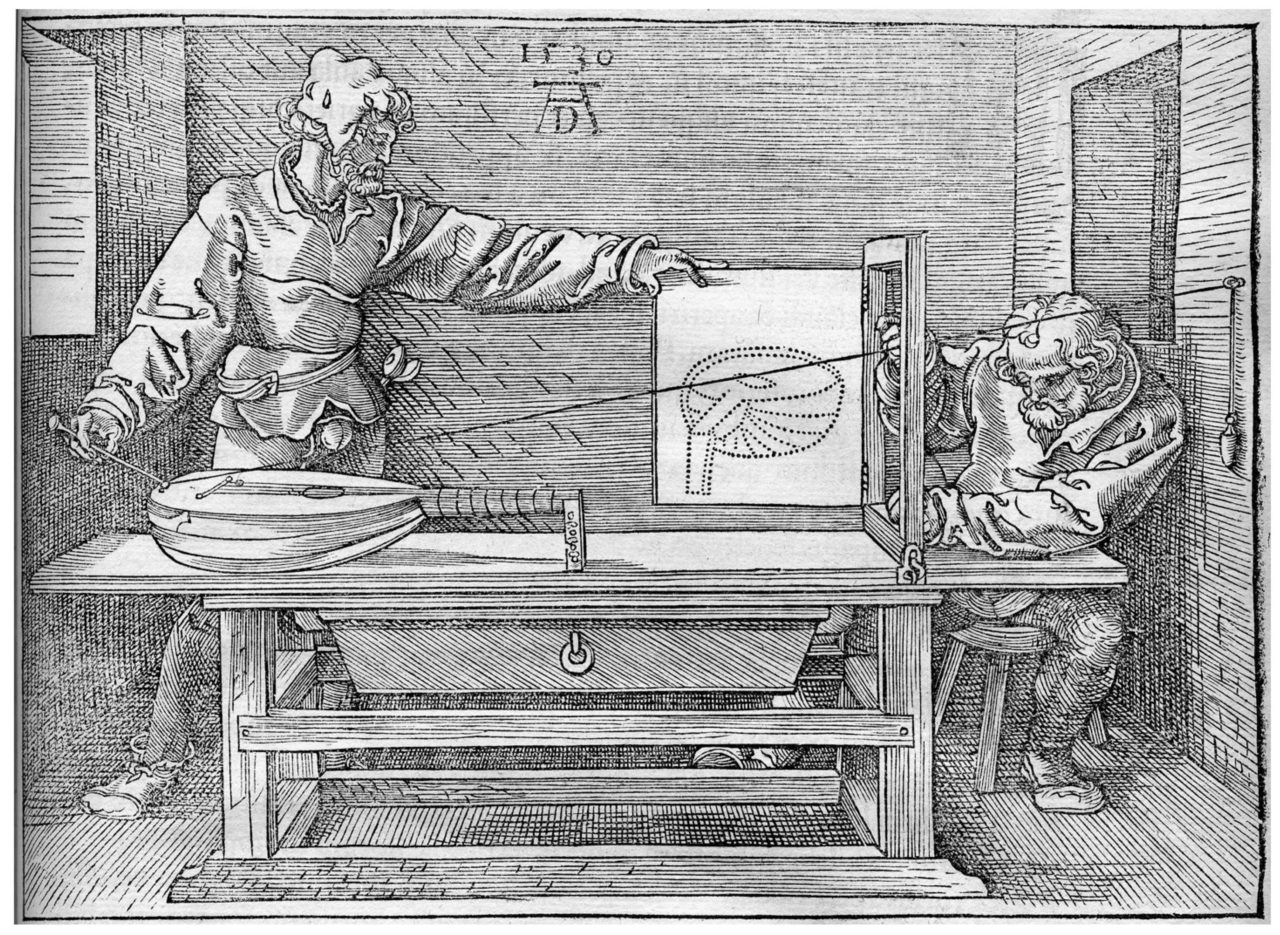

Consisting of a square wooden frame with a stringed or threaded, crisscross net—rather like a square-paned or leaded window—acting as a viewing grid for the artist, the perspective machine allows the artist to map out the scene before him onto a similarly gridded sheet of paper, aiding the measurement and comparative scale of objects in the distance. Albrecht Dürer draws similar set-ups in his woodcuts, Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman and Draughtsman Drawing a Lute (The Manual of Measurement), both 1525. These geometric devices gave visual artists of the Renaissance a claim to scientific precision, a precursor to the camera obscura and the photographic lens. Beyond ‘correct’ or convincing perspective, however, the power to section off portions of the visible world through mathematical means onto a picture plane gave rise to the notion of the painted image as illusionistic purveyor of truth.

-

Albrecht Dürer, Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, 1525

-

Albrecht Dürer, Draughtsman Drawing a Lute (The Manual of Measurement), both 1525

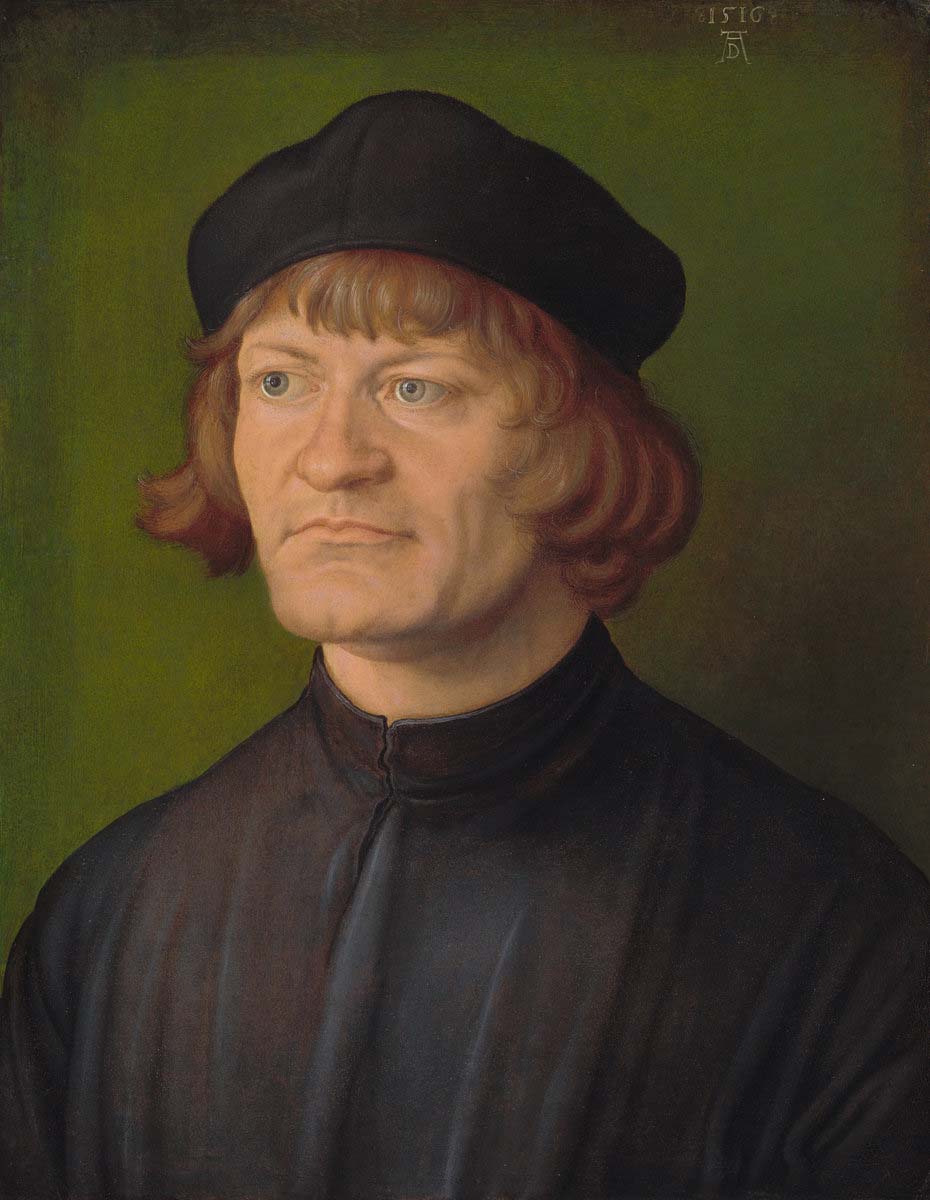

Dürer was one of the first artists to employ such hyper-realistic techniques, as he did in both his famed Self-Portrait of 1500 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich) and his Portrait of a Clergyman (1516, National Gallery of Art, Washington), which feature the tiniest renderings of a day-lit window reflected in the eyeballs of both sitters. This not only demonstrates Dürer’s intense commitment to detail and figurative faithfulness, but his attempt to go beyond mere likeness towards an interior light, or a depiction of the phrase that the ‘eyes are the windows of the soul’. Dürer later admitted in a Latin inscription on one of his other portraits to include the reflected windows in the irises that, “Dürer could paint the features of the living, but the learned hand could not paint his mind.” This conjunction of the mysterious and marvellous in the everyday (what William Blake called seeing “a world in a grain of sand”) elevates portraiture beyond the empirical to a philosophical or psychological pursuit.

-

Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a Clergyman, 1516, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alberti credited the invention of painting to the myth of Narcissus, who was so captivated by his own reflection in the water and his inability to possess the image therein that he killed himself: “What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of a pool?” (Alberti, 1435/1972, pp.62-63). In Caravaggio’s melancholic depiction (Narcissus, 1597, Rome Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica) the artist seems to admit that even he cannot recreate the mirrored likeness of the sculptural, gazing creature above, attempting only a blurry, murky clone in the depths of the water, one into which the central figure is almost melting and merging.

-

Caravaggio, Narcissus, 1597, Rome Galleria Nazionale dʼArte Antica

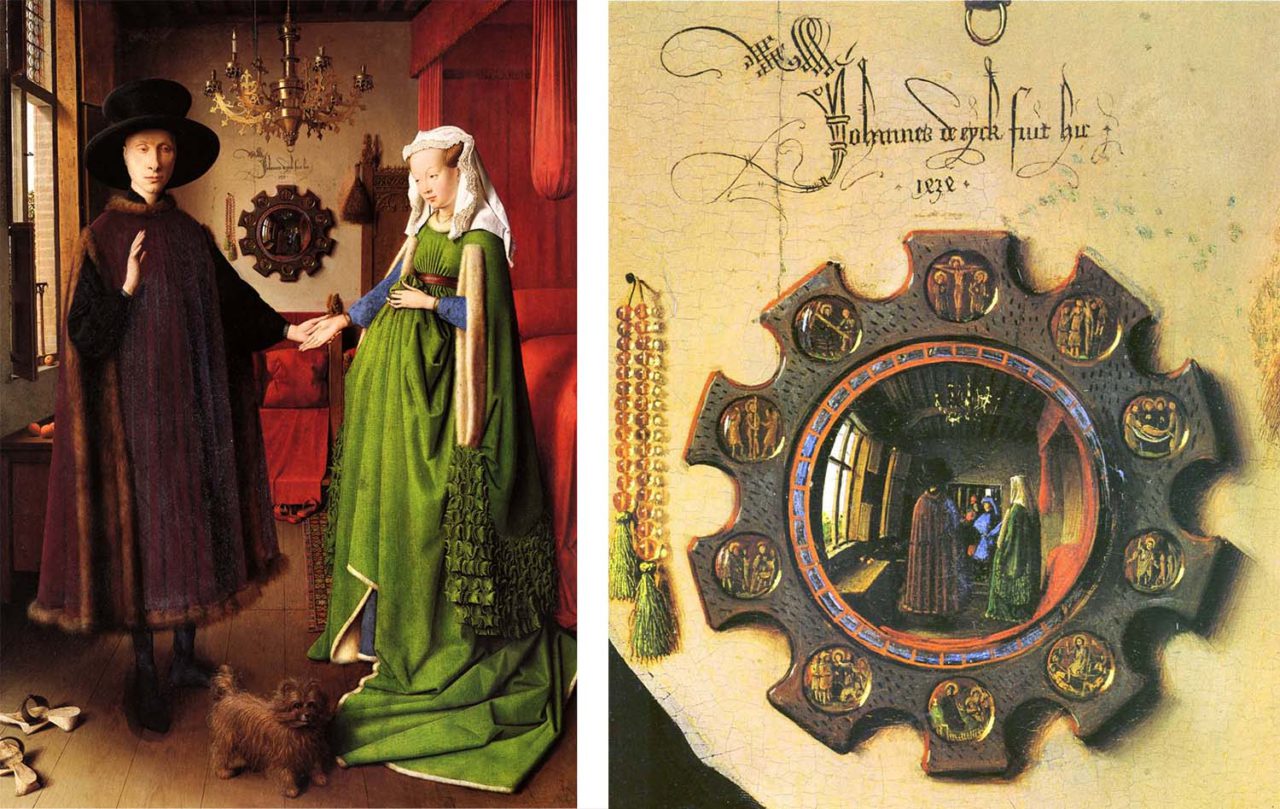

If the artist is only a conduit to nature and not its equal, then other uses of the mirror in the history of art suggest its reflective qualities as translators or channellers of a world beyond capture. Even though Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434, National Gallery London) includes a striking open window on the left, it is through the small central mirror at the heart of the composition that the true nature and wider context of this wedding day is depicted. Through this miniature convex mirror, the viewers become invited guests at this marriage between Giovanna Cenami and Giovanni Arnolfini. The painter was certainly a witness because his elaborate signature or sigil above the mirror is proof not only of his authorship but his presence, as he states ‘Jan van Eyck was here 1434’. And yet it appears that there might be another figure next to the artist in the doorway, effectively doubling this double portrait and its single, fixed point of view.

-

(From Left) Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, National Gallery London; Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait (detail)

An early example of an artist combining multiple vistas into one panoramic image comes in the Interior of the Church of St Bavo in Haarlem by Pieter Jansz Saenredam (1628, Getty Museum), in which a view towards the left of the Gothic building is spliced with a head-on study. These austere architectural interiors are like dazzling, idealised versions of reality—after all, the Dutch daylight rarely reaches such brilliant brightness and the building’s details are amalgamated from various visits and drawings from different vantage points. Every arch, doorway, window or architectonic feature leads the eyes beyond the flat surface into the depths of the picture, moving across, through and upwards to the heavens, guided by the tiny human figures and the vast soaring pillars and vaulted ceilings—ultimately to an appreciation of a higher power, beyond mere human creation.

-

Pieter Jansz Saenredam, Interior of the Church of St Bavo in Haarlem, 1628, Getty Museum, Los Angels

Rather than gazing from the inside out, the quintessential painter of Modern American life, Edward Hopper, looked in from his roving position on the outside of New York’s apartment blocks, coffee shops and offices. He haunted these locations on foot or even while he rode the Elevated or ‘El’ train, from where he could look down and into the habitats of regular New Yorkers, as in the voyeuristic Night Windows (1928, Museum of Modern Art New York). Although there is an erotic charge to watching a woman getting changed out of her clothes, the solitude of the spectator is made clear by the darkness of the exterior and in the cropped glimpse that he strains to capture in passing. Here the windows act both as Hopper’s eyes and our limited perspective on that most unattainable subject—other people’s interior lives.

-

Edward Hopper, Night Windows, 1928, Museum of Modern Art New York (c) 2020 Edward Hopper/VAGA at ARS, NY/JASPER, Tokyo G2269

Another artist born in the same neighbourhood of Nyack, New York where Hopper grew up was Joseph Cornell, a self-trained artist who lived on Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Queens—barely leaving the city limits his whole life (1903-1972). It was from his basement—crowded with thrift-store purchases and all manner of collected trinkets including maps, toys, shells and feathers—that he created his incredible and unique ‘object-boxes’, carefully composed windows into a private universe preserved beneath glass. As well as featuring his favourite singers and ballet dancers, Cornell also paid homage to Renaissance painters in his series of Medici Slot Machines of the 1940s, reproducing portraits by Caravaggio and Bronzino surrounded by marbles, springs and pages from books. He likened these works to slot machines because of his love of the penny arcades, shooting galleries and pinball machines in Times Square, perhaps even taking inspiration from the cheap local restaurants where he would gaze at sandwiches or cakes in their individual glass compartments. Cornell’s ‘shadow boxes’ may have mimicked an amateur, non-art pastime, favoured by the Victorians, but he elevated their status and that of his ephemeral collages and assemblages within to something approaching the spirit and consideration of the Old Masters whom he so revered.

-

Joseph Cornell, Medici Slot Machine: Object, 1942 (c) The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY/JASPAR, Tokyo 2020 G2269

As artists of the Modern era began to employ glass in works both as medium and as means to view their alternative visions, the architectural function of the window comes into play, both as viewfinder and reflective surface to experience our own bodies as protagonists alongside those beyond the dividing screen. Indeed, in the work of Dan Graham we become both the voyeurs and the actors or dancers on stage. His use of two-way mirrored glass as well as porous steel membranes also allows the spectators moments of privacy and anonymity, before then becoming the observed once more. According to Graham, “My pavilions derive their meaning from the people who look at themselves and others, and who are being looked at themselves.” The pavilions, which he began to construct in the 1980s, continued his psychological and spatial experimentation with video art from the previous decade, but entered the public sphere, challenging us to interact anew with our urban landscapes and those of the towers and office blocks we generally inhabit.

-

Dan Graham, Play Pen for Play Pals, 2018, courtesy Lisson Gallery

-

Dan Graham, Play Pen for Play Pals, 2018, courtesy Lisson Gallery

-

Dan Graham, Two V’s Entrance-Way, 2016, courtesy Lisson Gallery

Another use for the window or viewfinder in art is to take the intensely private into the public domain, as Cornell did in his very modest way, but more so in the last 20 years on a political level, especially in the work of artist and activist Ai Weiwei. After being released from 81 days of brutal detention by Chinese secret services in 2011, Ai began working on an epic series of life-like dioramas, entitled S.A.C.R.E.D (2013), set within six oxidised steel boxes, each themed according to a scenario of his incarceration: (i) Supper, (ii) Accusers, (iii) Cleansing, (iv) Ritual, (v) Entropy and (vi) Doubt.

-

Ai Weiwei, S.A.C.R.E.D, 2013, courtesy Lisson Gallery

Viewers approach each squat, tomb-like structure from one of two tiny viewing portals, behind which the dramas take place in hyper-realistic fibreglass, with every painful detail recorded from memory, rendered in half-human scale and uncanny likeness. Through these harrowing portrayals, Ai manages to both exorcise some of his own demons and accuse the authoritarian states that attempt to deny artists their freedom of expression, as well as their basic liberties. The work of art can be just such a metaphysical portal through which to discover another reality, whether that is one of truth, beauty or horror.

-

Ai Weiwei, S.A.C.R.E.D, 2013, courtesy Lisson Gallery

-

Ai Weiwei, S.A.C.R.E.D, 2013, courtesy Lisson Gallery

Works Cited

Leon Battista Alberti. On Painting (Cecil Grayson, Trans.) Phaidon. 1972. (Original work published 1435)

Ossian Ward

Content Director at Lisson Gallery (London/New York/Shanghai) and a writer on contemporary art. As well as leading the gallery’s communications and publishing teams he was co-curator of the major off-site exhibition, ‘Everything at Once’ and editor of the gallery’s 50th anniversary book, ‘ARTIST | WORK | LISSON’ (both 2017). Until 2013, he was the chief art critic and Visual Arts Editor at Time Out London for over six years and has contributed to magazines such as Art in America, Art + Auction, World of Interiors, Esquire, The News Statesman and Wallpaper, as well as newspapers including the Evening Standard, The Guardian, the Observer, The Times and The Independent on Sunday. Formerly editor of ArtReview and the V&A Magazine, he has also worked at The Art Newspaper and edited a biennial publication, The Artists’ Yearbook, for Thames & Hudson from 2005-2010. His book, titled Ways of Looking: How to Experience Contemporary Art was published by Laurence King in 2014. A sequel, Look Again: How to Experience the Old Masters will be published by Thames & Hudson in 2019.