Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 6: Beckoning Qilous

27 Oct 2022

Just about everyone in Taiwan eats similar food from the countless semi-outdoor dining halls there. The students all line up for newly opened chicken stores, and the old men dully slurp their wonton noodle soup. The young ladies working at department store reception desks scarf down garlic-filled dumplings during their breaks, and married couples head to sweets stores after finishing dinner. Living in this country will give you a strong sense of a kind of shared feeling created between people by food.

-

Night in Yilan, where everyone shows up on motorbike.

It’s most common in regional cities like Yilan, where I live, for everyone to come into the center of the city on motorbike when it’s time to eat. It’s the rhythm of the town, repeated every breakfast, lunch, and dinner the way one might come down from their second-story room to a first-floor living room. There are an incredible number of people in Taiwan who eat out for all three meals of the day, which has led to a great amount of diversity in individually-owned restaurants there. I also personally think that this culture of eating out acts on an infrastructural level to help make Taiwanese society one of Asia’s best for women’s social advancement.

When you’re here in the center, the “living room of the people,” you feel an odd sense of security even if you aren’t talking to anyone in particular. It could be because you know that everyone has the same goal of eating food. It feels like it’s rare to find a bad person who’s about to eat a meal. In any case, you get the strong feeling that one of the values one holds when living in Taiwan is that to eat is to live, a simple fact of human life.

It may be the smells that fill the city that give you this felling. The aroma of all kinds of foods, drinks, and desserts create a space that one can only experience there in the flesh. It also relates to how its buildings are made and used. One notable feature shared among Taiwan’s streets that gets brought up is that its lined-up restaurants’ openings are as wide as their entire building, with kitchens placed in the front. Preparation is not something to be hidden, but meant to be shown, while their smells of course drift into the street. These stores are built in a way to entice people through both sight and smell, and every day I find myself agonizing over where to eat.

-

A typical restaurant with the kitchen placed in front. (“Cow-Mama Beef Noodle Soup”)

The center of Yilan is packed with two- and three-story shophouses. The store portions on their first floors have open pilotis at the front, almost without exception. These sections are known as “qilous,” and they are mandated under Taiwanese law for any building above a certain width facing a street (8 meters in Yilan). These spaces suit Taiwan, with its harsh rain and sunshine, and they must be maintained there for the sake of pedestrians. It is generally prohibited to use doors and screens to partition these three-to-four-meter-deep spaces, as well as to fix any structures in place there.

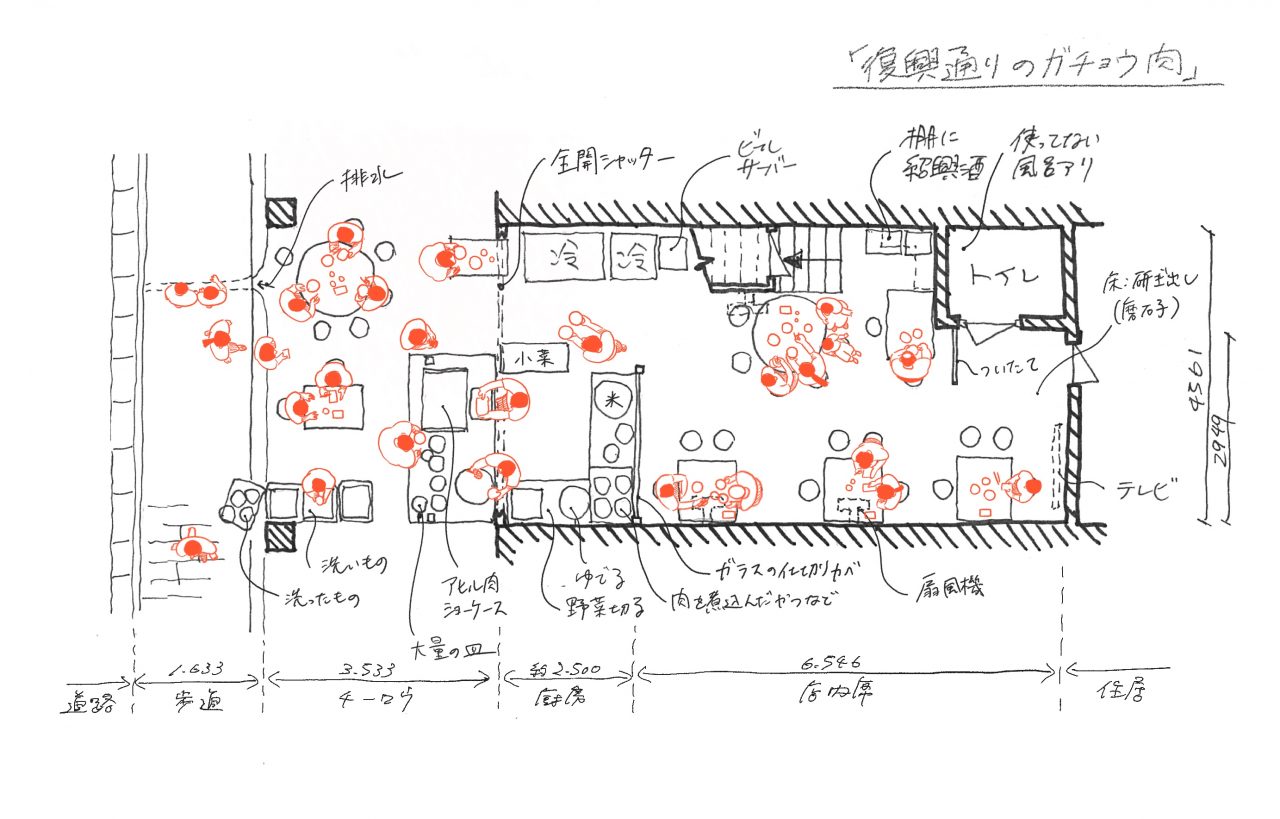

In order to maximize the use of these qilous, many store openings are built with shutters so that they can be fully opened up. As these go in up to three meters from the street, there’s no concern about sunshine or rain getting in.

I decided to try observing a dining hall I often go to, “Restoration Street Goose Meat,” from morning to night.

Morning in the city. The shutters for most stores are closed, and qilous can be seen serving their original purpose as pedestrian spaces. Excess kitchen equipment sits there in the qilou of the yet-to-open food hall. While extending a kitchen into these spaces is a legal grey area, a close examination shows that this equipment has wheels, as if to say it can be moved at any time.

2 PM. An older lady who works part-time at the store, which opens in the evening, has arrived. The store’s shutter is raised and the lady is busy cutting vegetables at a sink in the qilou.

Nighttime. Light shines from the rear of the store with its now fully opened shutter, while chairs and tables have been spread across the qilou. People are now gathering there, drawn in by the smell and the light. People spill out from inside the store while employees make and carry food by the entrance. The hectic scene makes it hard to imagine that things there were so still just this morning.

-

A floor plan sketch of “Restoration Street Goose Meat.”

Seeing lines of stores like these reminds me of the bazaar in Tabriz, Iran. The bazaars of the Middle East and Taiwan’s qilous. While they have completely different atmospheres, they both have the same sense of scale. While Tabriz was an arcade space featuring a series of domes, Taiwan actually once had a similar space in an oceanside town. Lukang, in west Taiwan, had a wooden arcade used to handle the weather that existed from the time of the Qing dynasty, but due to modern urban planning it has now changed to having qilous on both sides of the road like the sight I’m seeing on this day. Many Taiwanese people, including those in Lukang, came over from Fujian’s Quanzhou, where it’s known that many Arabs also lived during the middle ages. The roots of the Taiwanese people are truly diverse, so this mental association of mine may not be as off as it first seems.

Qilous are used in a variety of ways. In the mornings, when there are few people, they may be used as small temporary markets where meat is sold by weight, or they may be used as waiting rooms for clinics, as merchandise shelves, and as part of living rooms. So many different scenes of people’s lives spill out into qilous from opened shutters. Weaving through them while staying dry or unburned by the sun is part of the charm of Taiwan’s cities.

These qilou spaces were actually put into Taiwanese law as a part of “regional alterations” during the period of Japanese rule. It may be that qilous were already there in Taiwan and were simply brought to light by the law, but this law has remained even after the war, having a constant effect on the lives of the Taiwanese and the people living in Taiwan like myself, perhaps leading them to agonize each day over what to eat.

(Continued in isseu 7)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024