Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Taiwan

The campus of Taiwan’s first private university, Tunghai University, stretches across the suburbs of Taichung, a city in the center-west of Taiwan. It is Taiwan’s first Christian school founded by the United Board for Christian Colleges in China, headquartered in New York, after the Chinese Civil War between China and Taiwan.

The team of Takamasa Yoshizaka from Japan and Ching-Fong Lin from Taiwan won the 1952 competition to plan the school’s campus. While it’s unclear what happened next, I.M. Pei, a judge for this contest, ended up actually taking over the campus plan. Pei’s Luce Memorial Chapel (1963) is especially famous within this plan and is a shining masterpiece within the history of modern Taiwanese architecture. Architects from China, Chen Chi-Kwan and Chang Chao-Kang, were selected upon Gropius’s recommendation to assist with the working design for the campus (it’s thought that they in fact designed the majority of it), and the original campus was completed in 1960. It uses the elevated slopes in this area located a bit distant from the center of town as-is, and was planned as an asymmetrical campus even though it is centered around Wenli Boulevard, a tree-lined avenue. While I have visited a number of famous Taiwanese universities, this one stands out in particular. Each time I go, I imagine a life I could have had as a student, walking down this Boulevard with my classmates.

-

Wenli Boulevard, the center of campus

-

A courtyard surrounded by low buildings and dogs that sleep in the shade

The campus has been expanded again and again, with many new structures being built, but the original buildings continue to be used while also acting as cultural assets. The buildings are primarily simple structures made of reinforced concrete, and while they are modestly decorated, they weave together Chinese and Taiwanese elements such as wooden roofs, brick walls, raised floors, and inner courtyards with modern architecture. Its halls are almost entirely semi-exposed, and the students who walk along them are so full of energy. There are even dogs there freely sprawled out.

-

Exposed hallways and a courtyard. The area past the hallway is open.

-

A wood roof placed on simple reinforced concrete beams and pole plates

The campus is an incredibly open one, allowing anyone to come and go. When I arrived as an outsider, I wandered its halls from the law department to the literature department and could see the classes taking place there through the windows. While it’s built in a siheyuan style, with the departments surrounding a single courtyard, pilotis are used for their entrances. The corners of the four buildings that surround the courtyard are cut off, allowing the hallways to connect to the outside. Even if walls are present, they’re filled with holes made with embedded bisque pipes. This sense of being able to pass through from one place to the next gives this heavy style a sense of lightness and fluidity.

When discussing the architecture of Tunghai University, it’s standard to praise its design that combines elements of Chinese, Taiwanese, and modern architecture. But when I actually went there and walked around, this feeling of endless connection from one place to the next was even stronger, an element also made very important by Taiwan’s hot and humid climate. This ease of use must be the reason why its buildings continue to be used, despite multiple repairs.

-

A wall with embedded bisque pipes. They allow air to pass through while restricting movement.

-

Bisque pipes are also used for ventilation at the top of buildings.

Next, I’d like to introduce the building where I stayed at night, the Methodist Hall. It was completed in 1962, a little after the campus’s main buildings, based on a design by Chen Chi-Kwan. While it was apparently used as housing for female staff members at first, it is now used to accommodate guests. Chen Chi-Kwan would go on to head Tunghai University’s architecture department and design many buildings in Taiwan, but it seems he was best known for being an artist later in his life. This structure is entirely white, making it appear more modernist than the others on campus, but its design that incorporates Chinese motifs while also allowing air and light through makes it a small yet densely packed building, which drew my attention.

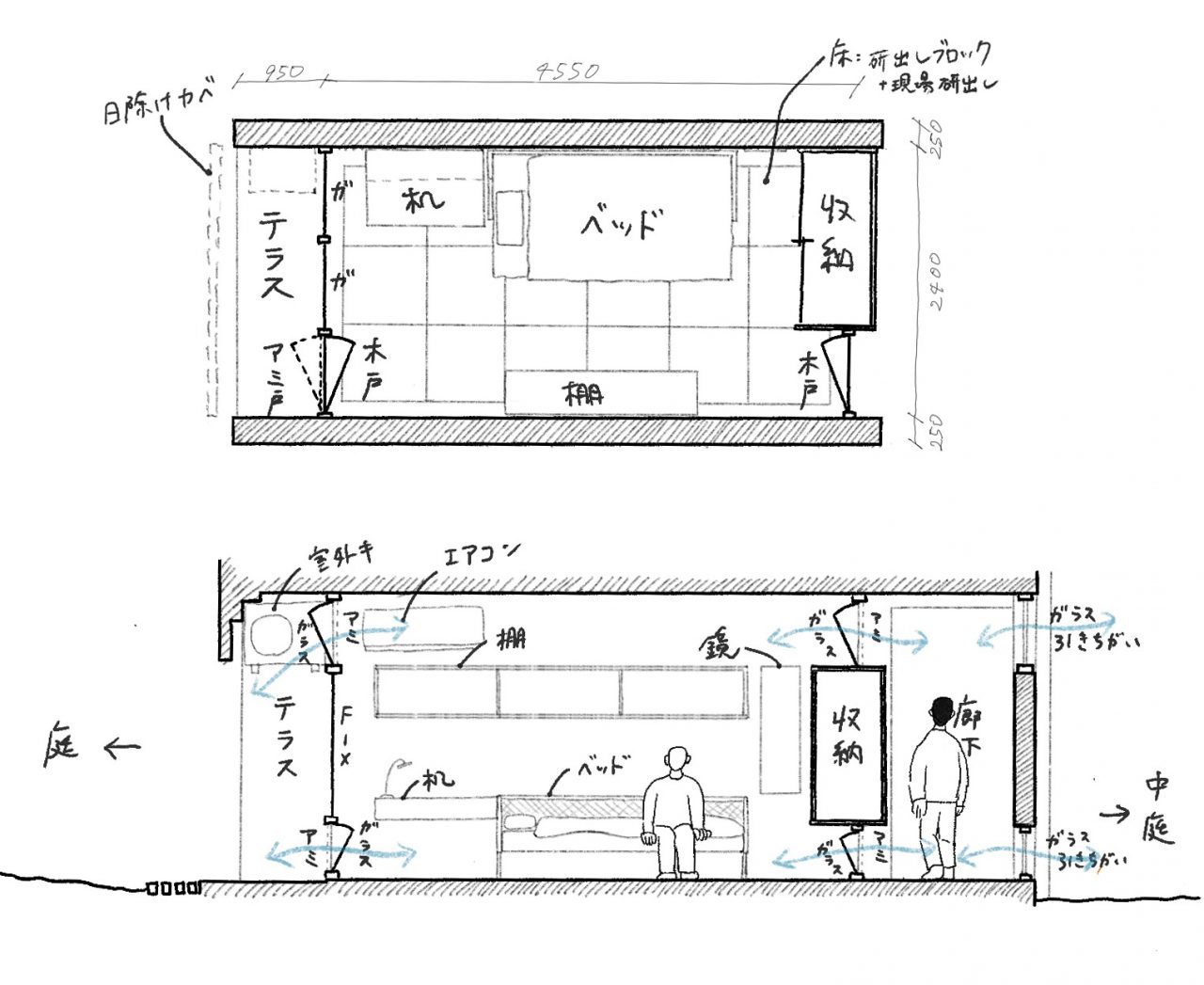

I stayed in one of the small private rooms that face the yard, and the yard-facing floor-to-ceiling windows were broadly split into three sections. The bottom sections opened inward, while the top sections opened outward. The large fixed windows in the center provided a view of the yard in microrelief. Looking back toward the hall, where the entrance is located, I could see this same three-section rule being used. The area that corresponds to the fixed windows acts as a storage shelf, while the top and bottom are also windows. This acts as a way to ensure enough airflow by using the top and bottom windows in each room. Furthermore, the built-in wood and rattan bed is lifted off the floor by four legs, while the cantilever desk juts out from the wall, allowing air to flow freely. When I went out to the hallways, I saw that the windows on the other side facing the courtyard were also open, making it clear that the building had a consistent plan for its windows. I would open and close the windows at night, and it was pleasant being able to adjust how much ventilation there was.

As for the common areas of the Methodist Hall, there is an open living room just after the entrance. When looking at the openable parts of its windows, we find louver windows that block out sunlight farthest to the outside, then two additional layers of windows in the form of screens and glass sliding doors. The louver windows can open outward and be fixed at a 90 degree angle, making them an important element of the building’s façade. The shelves below the windows are placed off the ground, and below them are ventilated, hit-and-miss windows that allow air to come in (a type also seen in Taiwanese homes). The U-shaped sofa in the center of the living room is also cantilever, lifted off the ground by jutting from the concrete walls. Like the bedrooms, it too seems to have a consistent desire to allow air by your feet to pass through freely, giving the building an extremely light and clean feeling.

There is a dining hall a half-floor down in the back of the living room, with a large round window reminiscent of Chinese architecture providing a view of the trees on campus. Getting closer, I saw the glass was divided into top and bottom, with screens running horizontally in small openings on both sides, allowing it to provide constant ventilation. This window may only be possible in a place like Tunghai, where even the winters aren’t cold.

-

The round dining hall window that provides an outside view

-

Screens used for ventilation in the center of the round window

The Methodist Hall did indeed have an interesting combination of Chinese elements and modernism. But at the same time, it is a structure full of details that take airflow and open lines of sight into consideration. Every space is joined somewhere to another, connected throughout from one place to the next. It seemed like a work that boiled down the entirety of this fluid campus, crystalizing it on an architectural level.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 10: The Billowing School—Chen Ren-He, Wave Building, San Sin High School of Commerce and Home Economics (Kaohsiung)

10 Jan 2024