Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 7: The Slate Village Down the Mountains: Pingtung

09 Mar 2023

There are now around 580,000 native Taiwanese (the term used in Chinese. In Japan, it seems the term “indigenous” is often used), representing 2.5% of the Taiwanese population. The government currently recognizes sixteen tribes, and while they may be more concentrated in some residential areas than others, they are considered part of the Taiwanese people alongside the Han Chinese that make up most of the population. There are native staff working at my office, and there are even native legislators. There’s nothing unusual about them if you live in Taiwan.

It seems that if you were to linguistically classify the native Taiwanese, they would be Austronesian language speakers. This language family stretches to Easter Island to the east, Madagascar to the west, and New Zealand to the south. The northernmost speakers are the native Taiwanese, and recent research claims that Austronesian languages originated with them.

Many of these natives once lived in the mountains, but their way of life was forced to change in many ways with the full-scale crossing of the Han Chinese from the continent beginning around the 17th century, the Japanese rule of Taiwan beginning in 1895, the post-war Kuomintang government, and more. While I do feel a bit taken aback as a Japanese person when learning about all of the history that has transpired here, I realize that as someone who lives in Taiwan, I must face this part of its past.

Many of the old native villages have fallen into disrepair, and barely any of the homes once recorded by Japanese academic Suketaro Chijiiwa in his Taiwan Takasago-zoku no sumika (The Housing of the Taiwanese People) still remain. It’s nothing like Japan, where you can find homes built fifty, or even a hundred years ago by going to slightly rural areas. I wrote about Orchid Island for the second and third installments of this series, and there I found concrete “cement houses” lining the streets just next to the few remaining half-underground homes of the Tao people.

The facility known as the Formosan Aboriginal Culture Village, located in the mountains of Taiwan’s central Nantou County, has restored many native homes based on Suketaro Chijiiwa’s research materials. With few old homes remaining in Taiwan, these documents are quite valuable. While these houses are generally simple ones made of stones or trees, the homes of the Paiwan people (the second largest native group) caught my eye in particular.

-

A restored Paiwan stone-slab house

-

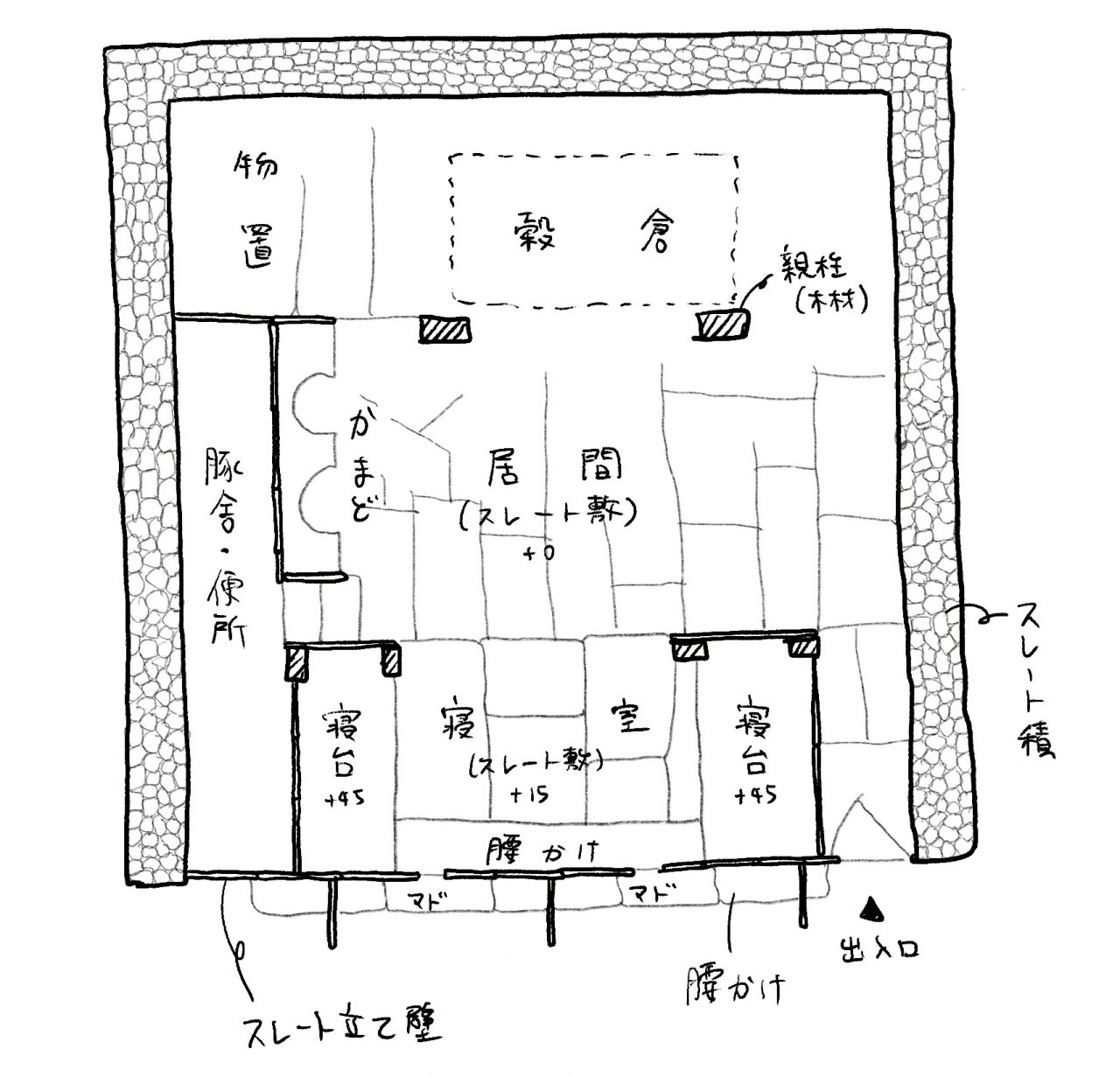

Floor plan of a Paiwan stone-slab house (Created by the author based off of Suketaro Chijiiwa’s Taiwan Takasago-zoku no juuka)

The home, known as a “shi ban wu” or “stone slab house,” is first surrounded on both sides and the rear with walls of thick stacked slate (many are thought to also have acted as retaining walls). The main structure and beams that support its typhoon-ready low slate gabled roof are supported themselves by the walls on both sides and internal pillars. Unlike the other three walls, the front wall is made of large slate slabs stuck into the ground that are a little over a meter across and 2-5 centimeters thick, acting both as walls and pillars. At the top, they’re inserted into large and ornamented pole plate grooves and held in place, while these pole plates are supported by pieces of slate resting diagonally at the front of the structure, a type of construction I’ve rarely seen before. While rather odd as a standard home for an ethnic group, slate must have been just that plentiful here.

-

The interior is entirely slate as well (dolls are used to recreate life inside)

-

A window with a sill attached due to an internal sliding door

I went inside to find that the internal floors and walls were also nearly all made of slate, making the place feel chilly. The Paiwan people once had a custom of burying family members who have passed away under the slate of the living room, but it’s said it vanished before the war due to “guidance from the authorities.”

The dark and cavernous house is lit by its entrance and two small windows. However, these windows are simple openings created by not stacking sections of the slate wall up to the pole plate. While wooden doors had been attached to the windows in this home, those in the more primitive ones simply consist of these openings, with no apparent way to open and shut them. Perhaps these are something like the origin of the window.

-

A primitive window with no fittings. The upper section is a pole plate groove where slate can be inserted.

-

Looking outside from an opening

The reason one hesitates to call these “windows” is likely because a window to us actually includes a frame and fittings as part of a set, such as a casement window or a double sliding window. This feeling of something being off may also be due to the way it is cut out from the wall using thin slate, unlike thick masonry walls. It also brings to mind the openings in the steel sheets seen in KazuyoSejima’s “House in a Plum Grove.” Indeed, the scenery seen from it was something special.

Hearing that there were still a small number of remains of a Paiwan village there, I headed to Kapayuwanan, located in the mountains of southern Taiwan’s Pingtung. It was recognized as a traditional settlement by the government in 2020 and has now become a place for learning where visitors can be guided by the Paiwanese.

I arrived to find a rugged, dark gray mountain. It seemed like you could take as much slate as you wanted from its slope that followed the mountain road.

-

The mountain bedrock used to build houses

-

A former village’s slate paths and stacked slate walls

Walking around the village, I found a few homes that have managed to survive. Most, however, have collapsed, leaving behind slate-paved roads and stacked slate walls as remains. I found a group of men repairing a home and decided to talk to them.

“This village was resettled as a group by the government around 1970. Everyone took parts of their houses with them, which is why the walls are basically the only thing remaining.”

I could imagine people descending the mountain while carrying beams and pillars. It was in this way that native Taiwanese villages were forced to move, resulting in barely anything being left behind.

-

One of the few remaining homes in good condition (thought to have been repaired). Wooden doors had been put on its windows.

According to this man, there seemed to be a town a little further down the mountain where people from a village like this one moved. Of course, this relocation must have resulted in more convenient transportation, medical care, education, employment, and more. I descended the mountain a bit to go to this town I’d been told about.

There, among the many “normal” concrete houses oftenseen in Taiwan, were the occasional houses that showed traces of traditional gabled homes. While some were built entirely out of concrete, others had only stacked slate on both sides. Some even had stone slabs located at the front. It seems that even if they come down a mountain and have different materials at their disposal, people will still build the same kinds of homes as before.

All the windows of these homes were noticeably larger, but I knew that their roots were in simple openings. I viewed the town while feeling like I knew just a little bit about the secrets behind its homes.

-

A home that still uses stacked slate. Its windows are larger.

-

A home that still has a slate façade. Its slightly old windows are made of wood.

A stout woman called out to me from one of the houses on the outskirts of the village, telling me I should have some coffee. This woman, who likely had native roots, smoked home-grown tobacco out of a pipe. She was a strange figure, wearing what resembled a witch’s hat. As we chatted, I glanced around her house. A large piece of slate rested against its tiled concrete façade, as if to hold something in.

-

A slate slab resting against a concrete house

(Continued in issue 8)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024