Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 10: The Billowing School—Chen Ren-He, Wave Building, San Sin High School of Commerce and Home Economics (Kaohsiung)

10 Jan 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Taiwan

When talking about the first generation of post-war Taiwanese architects, there are famous individuals such as Wang Da-Hong, who studied under Walter Gropius and were involved in many state projects such as Taipei’s Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall. However, it may be the case that not many modern Taiwanese architects are known at all in Japan.

Today I’d like to introduce works by a likely even less-known architect in this “first generation,” Chen Ren-He. In Taiwan, his materials have been archived in recent years and many people have come to learn about him. I first developed an interest in him when I learned that he graduated from Waseda University’s Department of Architecture in 1945, making him my distant senior. What’s more, while many members of this first generation were born in mainland China, Chen came from a rural part of southern Taiwan. The fact that he quietly created work after work in southern cities like Kaohsiung and Pingtung rather than Taipei also interested me. Wanting to see his work, I hopped on the high speed rail to go out and around the south.

In Kaohsiung stands Kaohsiung Buddhist Temple, which first brought Chen to the attention of the Taiwanese architectural world after he designed it in 1955. There beside a street highly trafficked by cars stood a strange structure of uncertain nationality, as though it lived in a world separate from its surroundings.

Looking inside, I found few signs of it being a Buddhist temple. It felt like a Western church if anything. Windows sit high on the second floor like a church’s clerestory, while passages surround it on all sides. Inspecting its Baroque-style oval arches, I could spot the kinds of lighting often seen in Taiwan’s Taoist temples, and architectural language from various regions mixed freely throughout the space. However, each one of these languages also felt like its own independent adornment. The windows were mostly cheap aluminum sashes, but the relationship between the light pouring in from unseen stairwell windows, its protruding spiral staircase, and its colorful polished walls was striking.

-

Light pouring in from a stairwell, as well as a protruding spiral staircase

I next visited the Donggang Catholic Church in Pingtung, notable for its large triangular roof and completed in 1960 in collaboration with a West German architect. As it is still in use as a church, many parts of it have been modified. Still, its intense shape made it stand out in the city.

Its spacious interior is warmed by the green and orange light that enters from the tall vertical windows behind the altar. It is simply made, with no extravagant materials in particular. The square windows placed alongside the sloping roof are plain as well, but they emphasize the structure’s feeling of ascent. Its overall shape and window placement seemed to have a more direct relationship compared to the Buddhist temple I saw earlier.

Of course, post-war Taiwan was under martial law until 1987. Considering its economic situation at the time, an architect with no institutional affiliation like Chen would be involved in many works with small budgets. Even when I look at a single window, I feel that he opted to make smart use of its placement rather than spend a large amount of money on its construction. Its floors are also made of terrazzo, as is commonly seen in Taiwan, while the simple benches lining the church are made of steel pipe and wood boards. This approachability must be the reason why Chen Ren-He is called “Taiwan’s first regionalist architect.” The neighboring building where its European priest lives is built of breeze blocks, as is commonly seen in the city, tempering the beams of the powerful south Taiwan sun.

The most striking of all the works by Chen Ren-He, however, was Kaohsiung’s Wave Building, San Sin High School of Commerce and Home Economics. As a technical high school, it was nearly empty when I visited on a day off. Many of Taiwan’s schools are generally open to the public, and fortunately I was able to enter onto the grounds of this one as well. I managed to find the building I was after from the courtyard, and its sight was quite moving.

Behind a line of tall palm trees stands a four-story school with all of its outside corridors billowing like waves. While outside corridors are a necessary space for schools in Taiwan’s subtropical climate (incidentally, Taiwanese films about adolescence make effective use of these outside corridors, perhaps making them into a necessary space for Taiwanese youths as well), here those corridors have been thoroughly shaken. Its entirely flat grass field only serves to emphasize this shape.

-

The courtyard-facing façade of the Wave Building, San Sin High School of Commerce and Home Economics

The undulating slabs, protruding by 2.7 meters in order to protect from the afternoon sun, are notably thin when seen up close (8 centimeters thick according to the blueprint), causing the beams that support them to pop out that much more. Like Kenzo Tange’s Kagawa Prefectural Government Office (1958), it brings to mind wooden construction despite being made of reinforced concrete, and one feels a sense of contemporaneity with post-war Japanese architecture when considering the building’s completion date of 1963. However, in this case there is less of a sense of proper wooden construction and more of the tasteful elegance of a wooden Chinese building that has grown warped over centuries.

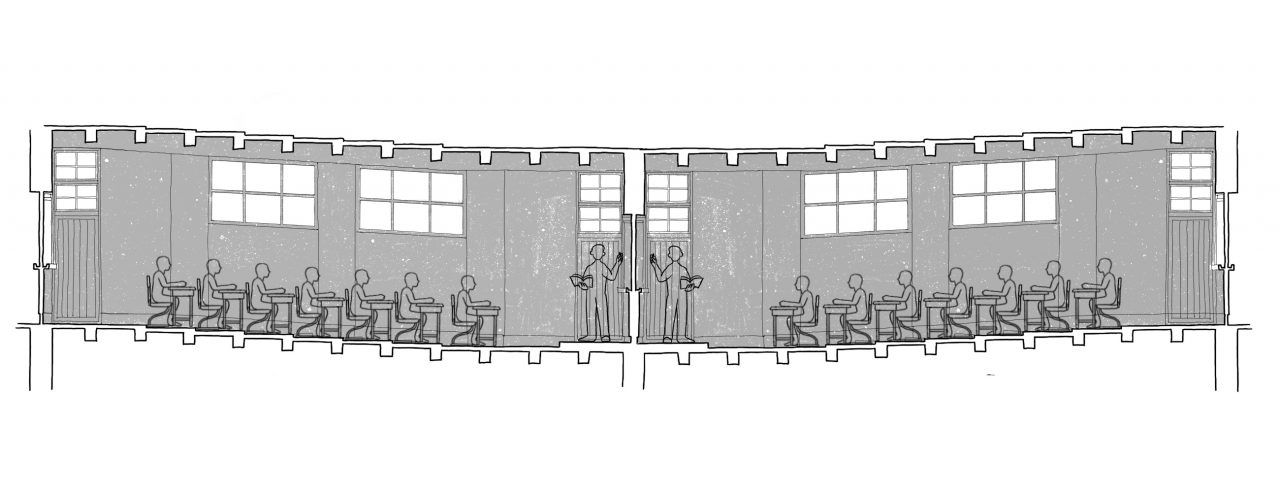

What’s shocking is that the building’s billowing extends beyond its façade into its interior spaces as well. While I regrettably could not enter inside, the interior of the school has tiered classrooms with 7 steps that are 5 centimeters tall and 90 centimeters deep, according to the blueprint. This resolves issues with students in the back being unable to see, and neighboring classrooms are thus back-to-back with one another. It could be that the school’s students remember their classrooms not by number, but in a physical manner, such as “just past the second wave from the edge.”

-

Light reflecting off the pond water and onto the slabs

What I thought to be handrails turned out to be concrete benches that also take part in the wave-like motion. I wish I could have seen crowds of students sitting on them. The shadows cast on the corridors rise and fall as well, creating an all-encompassing sense of undulation. This applies to its windows as well. Made of square aluminum sashes, they only have to rise and fall together with the building’s slabs to give not only its façade but even the inside of its classrooms a sense of rhythm. One must feel like they’re located inside a kind of large movement when taking classes here.

When you actually look at Chen Ren-He’s blueprint or post-construction photographs, though, you can tell that these were originally parallel square windows that follow the movements of the slabs, and that these openings were only located on the top 120 centimeters or so of each floor (see blueprint). He surely meant to use the overhanging outside corridors together with the high openings to block out the afternoon sun. But modifications are inevitable after sixty years, and these have now become large windows unlike those in the original design. It seems that for disciplinary reasons, classrooms must be visible from corridors in Taiwanese schools, and this kind of national educational environment may have had something to do with this change as well. While the windows have become square ones in this modification, they can still be said to maintain their relationship to the building’s overall waves.

-

An undulating slab façade and the originally designed windows

While I once considered how the timelines of a structure and its windows could diverge after once seeing an old settlement in Iran (Traveling Asia through a Window: Masuleh), perhaps the same could be said even about modern architecture that is kept alive through preservation. The divergences in a building’s windows quietly tell us about the times and societies that it has seen.

This structure is so clearly one of Chen Ren-He’s end points because of the strength of its architecture. Whether overall structure or function, everything about it, including its windows and more, comes together as a wave, even after modifications. Perhaps that is why it is considered his most famous work.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024