Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 9: The Windy County Office—Yilan County Hall (Atelier Zo)

31 Oct 2023

While this column has primarily introduced the windows of unnamed buildings in Taiwan, there are a number of works of modern and contemporary architecture that I would like to discuss. One such structure is Yilan County Hall, built in 1997 by Atelier Zo. Though I’d seen pictures of this building in books as a student, I learned about its true condition after coming to Yilan. As I’m involved in many public projects in Yilan County through my firm, I naturally have many opportunities to have meetings and give presentations inside of it. Having “used” it in this way for about six years, I’ve come to believe it to be a masterful work of architecture.

Atelier Zo first came to Taiwan, and specifically the small county of Yilan, for the Dongshan River Water Park (1994). It seems that Zo was able to design this water park, the first in Taiwan, thanks to an introduction from landscape architect Kuo Chang-dwan, who studied at the office of Takamasa Yoshizaka. Their work and their approach to design must have been appreciated by many, as they were then asked to oversee the new county office in Yilan, which was then still a rural area. Many people come and go here from morning to night, even after twenty-six years have passed. What’s most important, though, is that it is an incredibly pleasant building, matched perfectly to the styles of work and life in present-day Taiwan.

-

The greened roof. People are free to climb up and visit. Visible in the rear is the city council, also built by Zo.

-

An older woman napping on a hall bench.

This building doesn’t have one standout external view, making it difficult to grasp. It’s so large that one can only photograph it in portions, with each and every surface having its own expression. It’s built in a way that only one small part can be taken in at any one time, which must be why it feels more like a place than a single structure.

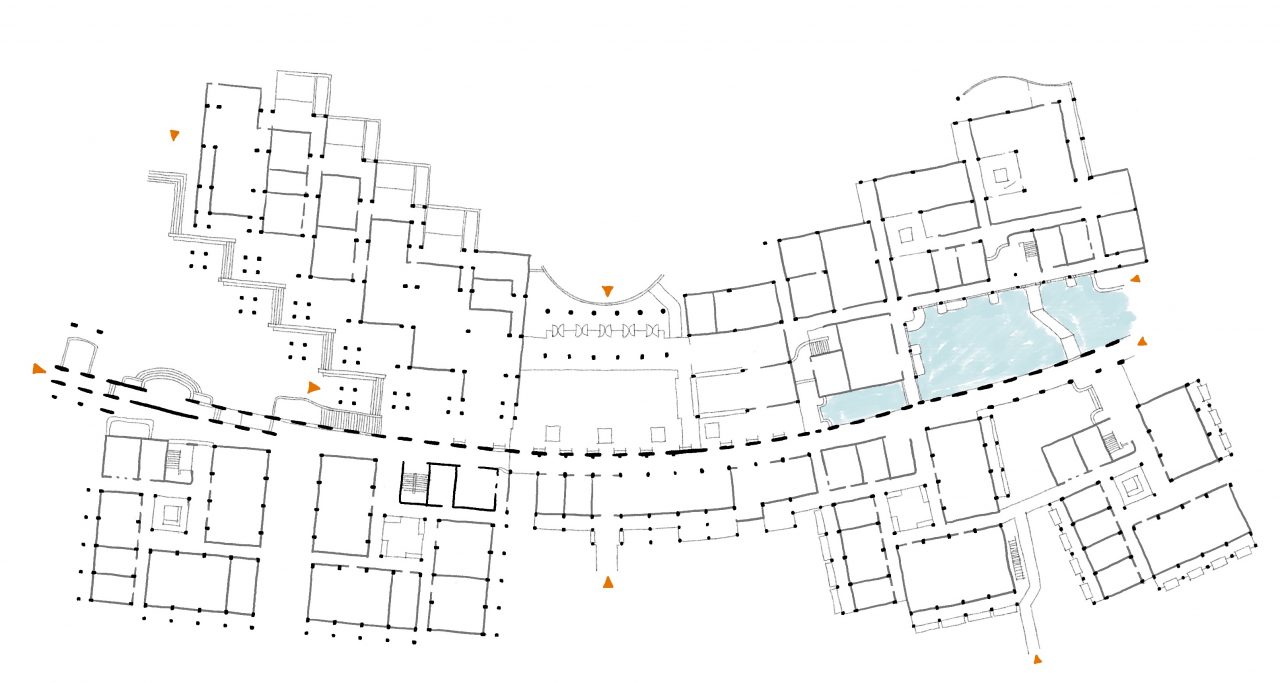

A floor plan greets you as you enter inside. Its long, curving hallway (its center acting as a courtyard for the entire hall) also gives it a sense of depth, as you’re unable to look across its entire length. What’s surprising is that almost every path in this structure, its hallway included, is half-exposed to the outside. Furthermore, both officials and citizens can enter and exit this hallway from its many entrances at all hours of the day. There is a proper roof to block out the sun, and both people along with the wind sweep through the dark (at times even too dark) space it creates. There are barely any bright white spaces here lit by fluorescent bulbs. You can generally tell what time of day it is when you use this building, to give a more intimate illustration.

There’s a large lake at one end of the hallway that chills the passing wind. This seems to be a piece of wisdom from Islamic architecture, and it is indeed quite cooling. I was impressed that they were able to make a hallway that feels pleasant even during the height of summer. It reminds one of the breezy shade commonly seen under Taiwan’s banyan trees, or its qilou.

-

The floor plan. The building has many entrances. The curving hallway can be seen here. The hall is at its center, and the blue portion is a lake.

It’s not just the lake, either. For whatever reason, the architecture of this building uses many motifs from Islamic architecture. There are lines of various arches along the hallway, while the windows cut out from its pink lattices create deep shadows from the powerful light of the sun as though they were Taiwanese mashrabiya. The mashrabiya is a technique used in Islamic architecture that has the effect of softening sunlight while also providing privacy, but it can in fact be found all over the world, including in Greater China (Japan’s lattice windows may be connected to them as well). While many wood-carved latticed doors can be found in Taiwan’s traditional architecture, a careful inspection of these shows that they have a polished pink finish (also known as Terrazzo [mó shí zǐ] in Taiwan). No discussion of Taiwanese architecture is complete without this beautiful plaster work technique particularly seen in Taoist temples. I would like to write about these too one day.

There are also swastika-patterned lattice windows, and they all are able to play with light and wind because this is a half-outdoor space. Zo used many concrete blocks to create shadows at Nago City Hall in Okinawa, and this structure appears to be a great step forward from that, even in its shaping.

Meanwhile, skylights are used to bring light in to segments of the building not facing its hall or the outside. One space under a skylight is painted completely blue, coloring the entire world contained in this corner. A sign hanging there that reads “labor administration department” is the only reminder that one is inside a government building. These skylights are glassless openings, allowing hot air to leave and rain to enter. This too is a different kind of space, chilly in part because of the color.

You can see many different kinds of people in this place. Government officials, county residents, people visiting the post office, people coming to the café, people who seem only to be there to cool off, and people napping (incidentally, it seems that naps are compulsory for the Taiwanese as early as elementary school, and that they’re a vital part of the day even for adults). The sight of this county hall, where people come and go from its entrances too numerous to count, almost seems to embody the close relationship between Taiwan’s administration and its people. You can see inside many of its rooms through wooden glass doors, making the meetings there truly transparent and open-air. One could even walk right up to the county magistrate’s office if they felt like it. Former county magistrate Chen Ding-nan’s concept of “creating parks through architecture / putting the people first through architecture / indigenization through architecture” at the time of its construction is shockingly clear in its embodiment.

Personally, this building is right by where I live, and so I sometimes bring my dog to its café before work and eat breakfast there. This county hall isn’t just open to humans, it’s even open to animals. I love the feeling of sitting on the terrace under its deep eaves and enjoying my morning as I watch government officials heading to work early in the morning. The young women working at the café bustle around, speaking to each other in loud, cheerful voices. A few people in suits talk about work from their corner seats. Just as windows can take on many different shapes, people here can all coexist simultaneously on an even field. It’s this way of life that I believe accurately represents Taiwan today.

(Continued in issue 10)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024