Part 2: Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

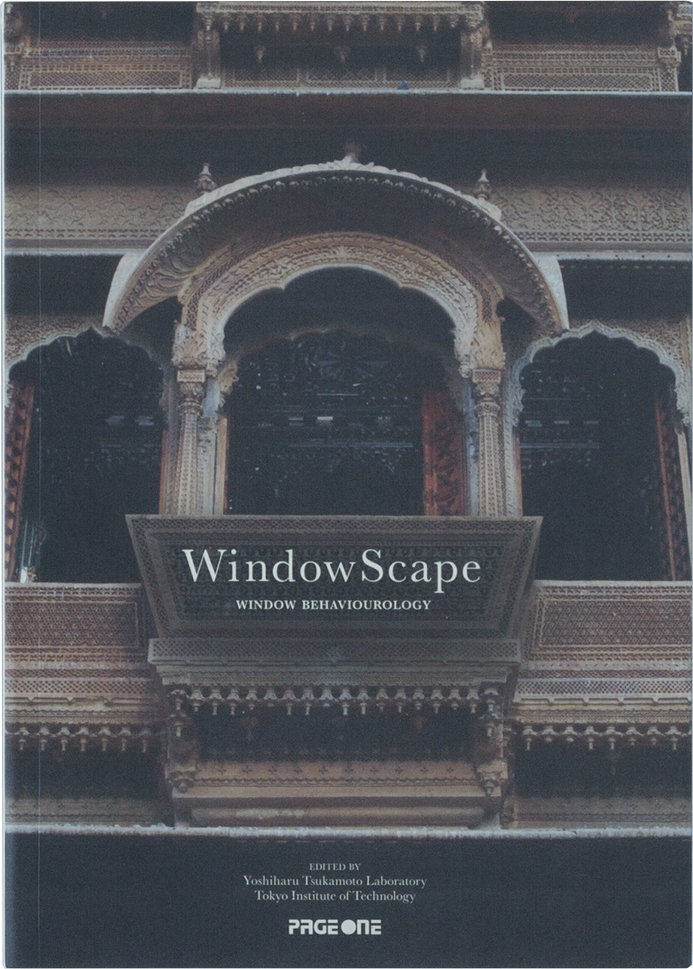

“Window Behaviorology”

13 Nov 2018

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

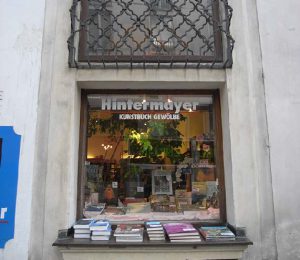

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (Architect, Atelier Bow-Wow) has conducted “Window Behaviorology”, an extensive field work on windows around the world, since he joined Windowology in 2007. In the second part of the interview, Tsukamoto explains how he has incorporated findings from the field work continuing over 10 years in his architectural practice by showing two recent projects by Atelier Bow-Wow, a student housing in Munich, Germany and a research library in Muharraq, Bahrain.

Student apartments Munich

In Part 1, you talked about how you think about architecture from a viewpoint of “human behavior” and the trajectory of your research up to the point when you began “Window Behaviorology.” In Student aprtments Munich, What kind of windows are installed on the building?

One can observe repetitions of bay windows on apartment facades along the streets in Munich. Bay window spaces are the best “rooms” in the apartments. They are like salons equipped with chairs and a desk where one can enjoy views of the city below. Window spaces are considered as small additional rooms within rooms. We incorporated these window spaces in the student housing and proposed new generation bay windows. Single room units with a window are repeated along the facade. Windows influence the way they live and also the overall impression of the building. A bay windows adds a small space to a room that is big enough to accommodate a bed or a desk. At the same time, the project allowed us to reinterpret townscapes and street-side architectures in Munich. It was like bridging the past and present.

-

Student apartments Munich (2017), Atelier Bow-Wow and Hannes Rössler

In Europe, they usually hire an architect called “City Architect” in a city council’s building department. In order to obtain a building permit in a city in Europe, one needs to obtain an approval from the City Architect, which means that the City Architect is practically in a position to control the direction of architectural design in the city. In our case, the City Architect liked our proposal very much. Basically, young people who come from somewhere outside of Munich live in this student housing. He thought it would be a great experience for them to live in a building designed with reference to streetscapes in Munich.

Unfortunately, this project was sold to another developer halfway through the project. The new developer decided to reduce the number of bay windows and change public spaces on the first floor to single room units to increase profits, and resubmitted updated documents for building permit. But the City Architect told them to scrap all changes and return to the original plan because our design was excellent, and the building was completed according to the original concept. I think our design was approved because we put our priority on designing windows with an aim to connect the building to the city. The City Architect probably wouldn’t have supported our proposal if we hadn’t done that.

Streetscapes are treated in completely different ways, comparing Japan and Europe.

Some of the streetscapes in Europe are turning into something like museums, which is a matter of concern. When traditional streetscapes become tourist spots, outside investors come in and rents rise, and people who had been renting apartments can no longer there. Building owners often live in the suburbs and their original homes are rented to foreigners who use them as second houses.

In Tokyo, city residents are not subject to pressure from the tourism industry, because the existing streetscapes generally have no touristic values. If we look at it from a different angle, we can effectively use the pressure from the tourism industry to increase values of the city. We are currently discussing how to utilize the power of tourism to activate community development planning in Japan, but many architects are concerned that tourism causes damage to subject areas and promotes commercialization. But we can use the energy of tourism to renew and reinforce communities that provide basic conditions of people’s daily life. We incorporated this viewpoint in the student housing in Munich.

Repetition of windows and streetscapes

In “Windowscape”, we observed behaviors gathered around each window. We expanded the scope of observation to streetscapes composed of repetitions of windows in “Windowscape 2: Window and Streetscape Genealogy.” If we look at streetscapes as repetitions of windows, we could say that preservation of streetscapes is about preserving repetitions of windows. We incorporated findings from this research very effectively in the design of student apartments Munich completed in 2017.

-

Streetscape facing Grote Markt in Antwerp, Belgium. Windows take up a larger part of the facades than walls, and middle floors are composed of repetitions of three to five vertical windows (Research “Window and Streetscape Genealogy”)

-

Streetscape in Furukawa-cho, Hida-shi, Gifu Prefecture. Machiya or townhouses in a special style (a townhouse into which a kura or storehouse is inserted perpendicularly) line up along the street. Aluminum window frames on houses and ventilation windows on storehouses alternately appear (Research “Window and Streetscape Genealogy”)

While most people may associate the word “behavior” with humans, heat, light, and wind also “behave” in certain ways. Even architecture, considered immobile, “behave” in certain ways when observed on a long time-scale. A behavior repeats itself. That is why a behavior tends to be affected by qualities of ordinary things.

In addition, its repetition is based on a certain rhythm. For instance, a behavior of light changes quickly but a behavior of heat takes a longer time to change. A person’s behavior ── for example, waking up in the morning, working or studying during the day, and going to sleep at night── maybe based on a day-long rhythm, while his/her other behaviors may be based on weekly or annual cycles. On the other hand, behaviors of architecture are often based on 50 to 1000 year-long rhythms.

In Japan, houses are demolished and reconstructed every 30 years in average according to statistics, and this fact also indicates a certain rhythm of a specific behavior. Many things can be understood by observing how rhythms of different behaviors overlap.

Research library in Muharraq

Would you tell us about your recently completed project in Bahrain?

We started designing this building as a research library specializing in art and architecture, but it became a place to introduce research conducted by an organization called CERN in the end. It is a library not exclusive for researchers but open for public use.

The building is located in a fishing village called Muharraq that once thrived on pearl cultivation. Its traditional streetscapes are registered as a world heritage site. Since the building was located within the heritage site, we had to adjust the building volume to match the surroundings. We reinterpreted and recomposed a vernacular architectural style of the region to accommodate a contemporary architectural program.

-

Research Library in Muharraq ⒸAtelier Bow-Wow

-

Research Library in Muharraq ⒸAtelier Bow-Wow

Positions of windows on buildings in this region are quite interesting. In Islamic cities, windows are basically located above eye level so that interiors of houses are not visible from the streets. The latticed bay window in the photo, looking like an alcove projecting outwards, is called “mashrabiya.” Just like the way Islamic women cover their faces for religious reasons, mashrabiya prevents women inside a house from being seen from outside. Mashrabiya can be observed in many places in Islamic cities and there are mashrabiya made of stone in India.

-

Windows of a house in Safranbolu, Turkey. Women who are not allowed to show their figures in public for religious reasons can have a view outside from latticed windows (Research “Window Behaviorology”)

In this building, we made mashrabiya slightly larger than usual and turned them into reading spaces. We designed very gently sloping stairs and provided several landings respectively equipped with mashrabiya along the way. Seen from outside, mashrabiya repeat at different heights, creating rhythms on the facade, and silhouettes of people reading beside mashrabiya can be seen from outside. These are new generation mashrabiya based on reinterpretation of traditional ones.

They are traditional yet new, and familiar yet innovative. They were well received by local residents. The east facade along the street, on the other hand, is shady during the day and kids play soccer there. So, we made the wall windowless and sturdy enough so that kids can hit the wall with soccer balls as they wish.

-

Research Library in Muharraq ⒸAtelier Bow-Wow

-

Research Library in Muharraq ⒸAtelier Bow-Wow

When you develop a design based on a viewpoint of “behavior”, I suppose you need to do a lot of research. How do you start a research?

The best thing is to go visit somewhere. Go somewhere, find whatever interests you and dig further. Basically, we learn from a town what is considered important there while we develop a design. That’s why we don’t do a lot of research at the beginning. It is impossible to start doing something after we have learned everything. That’s what is interesting about architectural design. There are naturally some things we hadn’t noticed previously, and we incorporate what we found in the next project from the beginning. Although we may sound as if we knew everything from the beginning when we present our design….

In terms of window production, do you collaborate with local craftsmen and manufacturers in overseas projects?

This time we were introduced to several wood workshops and worked with local architects and people in their network. We had a few discussions regarding how to make lattices. The thing is, we don’t ask them to do something they have no knowledge of, because our design is based on things already existing in the area––such as mashrabiya. So, things usually work out well wherever we go. That’s a good thing.

Windows made by Northern European architects

You are currently conducting research in Northern Europe as an extension of Window Behaviorology.

Three or four of my favorite architects who were active in the early 20th century are from Scandinavia. Gunnar Asplund from Sweden, Alva Aalto from Finland, Arne Jacobsen from Denmark…. and Jorn Utzon also from Denmark, who belonged to a younger generation. We are visiting and conducting research on windows these architects had made throughout their careers until next year.

-

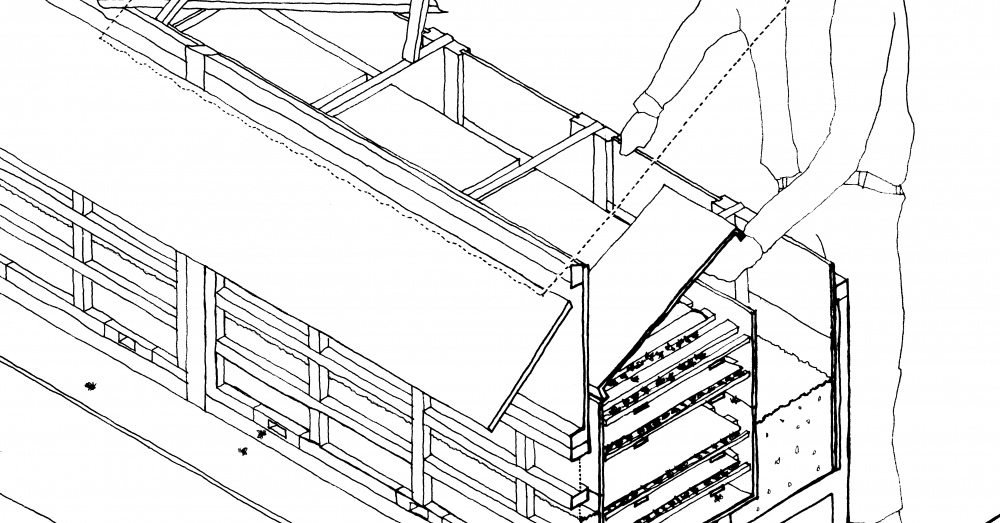

Windows at the reading room in Paimio Sanatorium designed by Alva Aalto(1928-33). Two windows can be opened simultaneously by pulling the chain to make gears rotate (Research “Windows Straddling the Ethnographical and Insdustrial Networks”)

In this research entitled “Windows Straddling the Ethnographical and Insdustrial Networks”, windows in the pre-industrialization era are referred to as “Ethnographical windows.” Ethnographical windows and industrialized windows deeply intersected each other in the early 20th century. Today, information industry is taking over machinery industry and expanding the market. The same kind of changes were occurring during that time. In this sense, it is important to examine changes that occurred from the late 19th century to the 20th century when thinking about changes in our era.

We are going to look into how architects of the time viewed new technologies, incorporated them in their practice, and adjusted them to suit common sense of the era they grew up in.

These Northern European architects are different types of Modern architects compared with Le Corbusier in France or Mies van der Rohe in the United States. They were reluctant to let go of Ethnographical things, or perhaps unable to escape from them, but they respected the continued lineage. That’s what I like about them. I would like to reexamine the significance of the windows they had created through the research of “Windowology.”

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1965. Graduated from Department of Architecture, Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT) in 1987. Studied at Ecole Nationale Suprieure dʼArchitecture de Paris-Belleville (U.P.8) in 1987–88. Co-founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Momoyo Kaijima in 1992. Completed Doctoral Degree Program (Ph.D. in Engineering), Graduate School of Architecture and Building Engineering, TIT in 1994. Appointed Adjunct Professor, Graduate School of Architecture and Building Engineering, TIT in 2000 and currently serving as Professor at the school since 2015. Visiting Professor at Graduate School of Design, Harvard University in 2003, 2007, and 2016. Visiting Associate Professor at UCLA in 2007 and 2008. Visiting Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2011–12. Visiting Professor at Polytechnic University of Barcelona in 2011. Visiting Critic at Cornel University in 2012. Visiting Professor at TU Delft in 2015.