Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 5: The Matsu Islands: Small Windows on the Frontier (Part 2)

20 Jul 2022

The first morning of the new year arrived as I stayed in my room on the frontier, and I decided to survey the quiet guesthouse before my friends woke up.

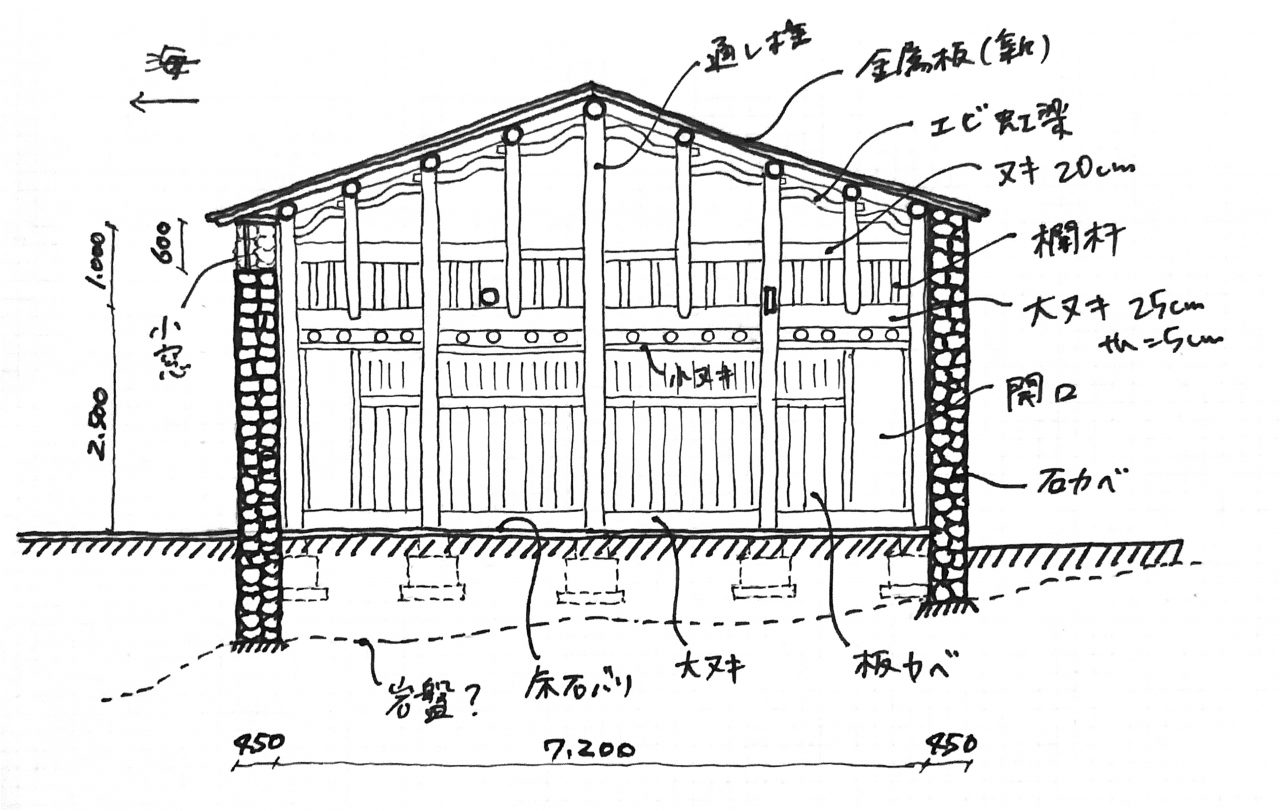

While the stonework building appeared to only be one story from the outside, an attic had been built inside of it, which is where we all slept. It contained a square window with sides about 60 centimeters long, and from it I could see the sea glittering in the morning sun. Located just under the building’s eaves, the window was made in order to provide light to the room. Creating a window just under a roof must have removed any need to use a large lintel stone. Also, because its height had been shortened in order to minimize the effects of the sea breeze, the lowest portion of the attic was only one meter tall, making it impossible for people to stand straight there.

-

The attic room and its window

-

The morning sea seen from the window

While this structure’s outer walls are made from durable stones, the floors and ceiling on the inside of them are made using its wooden post and beam framing. I’d seen this nested style of house before in East Tibet. It’s a building method often used in China. Though construction can be broadly divided into the two categories of masonry and post and beam framing, there are many structures around the world that can be called a midway point between the two. These are soundly built houses that are earthquake resistant yet changeable, incorporating the best defensive elements by taking a wooden post and beam structure and essentially fitting it with thick stone “pants” (also often brick in China, or even rammed earth walls).

People decide on a course of action after a negotiation between rationality, beauty, customs, coincidences, and other choices made over long periods of time. What’s interesting about looking at houses could be the moment that you come across this state. This is how houses sometimes acquire a complexity that can be hard to understand at first glance.

-

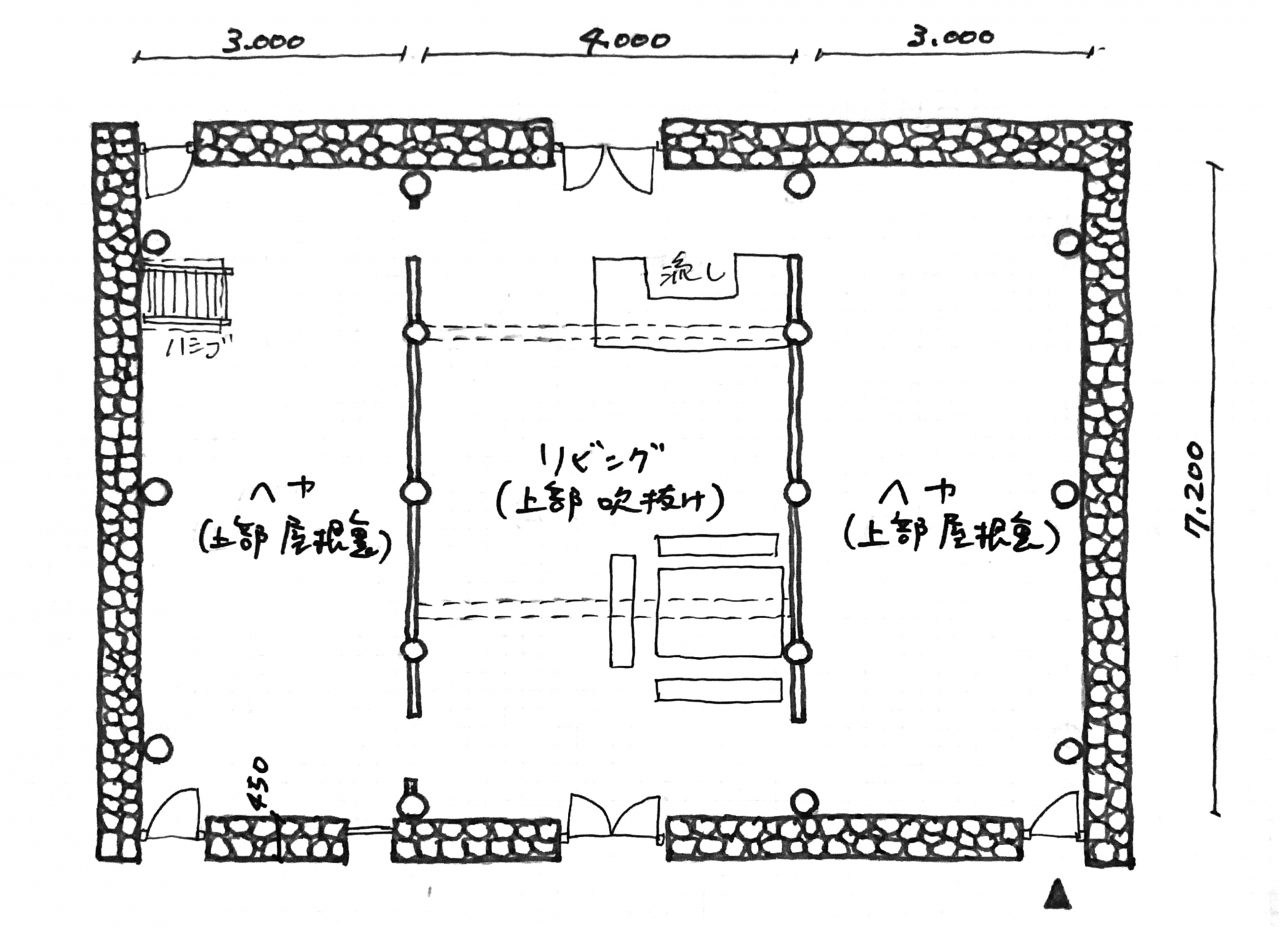

Floor plan of a house in Nangan. Wood posts stand on the inside of stone walls.

All of its deep amber posts were round columns, and the two rows of five pillars each standing in the center of the structure were connected by curved beams. Shrine and temple construction in Japan also used such ebikouryou beams as early as the middle ages as components to connect posts of different heights. Though a rough form of construction, it seems that this technique was even used in regular houses on the island until about a century ago.

Taking an even closer look at the floor plan, you’ll see that there are only three posts along the walls on each side, and that they are offset. These posts aren’t used to fix the four corners of the structure. This could be related to the fact that the house isn’t entirely a wood building. It seemed that the weight of the ceiling is given to the pant-like masonry on both sides, with the posts playing a supporting role at best. This structure that mixes wood and stone construction is the result of the island’s accumulated ingenuity.

I then headed from Nangan by boat to another large island, Beigan. The island contains the village of Qinbi, which is full of stone houses. It seems to be well known for its landscape, called “the Greece of the East” by some. Though not as white as Greece, and while its sea is murky, it was indeed a photogenic village. Its stone houses were buried inside of cliffs also made of stone. The terrace spaces in front of its houses were tied to one another, causing its streets and yards to mix together. Walking around the village was a complicated task, as I couldn’t figure out how to get to locations despite them being within sight. Messages from the military such as 解救大陸同胞 (rescue our brothers on the continent!) hung here and there, and the island even contained a place where a loudspeaker is installed in order to appeal to those on the continent that “life is good here.”

-

芹壁村全景

Here I stayed in one of the village’s oldest houses, the Wanghailou guesthouse built 150 years ago. Its talkative host told me about the house while treating me to some alcohol brewed using red yeast rice. Despite it being my first time trying a sip, something about the flavor felt nostalgic.

The man snorted as he explained to me, “While a lot of the buildings on the island might look like stone, they’ve actually been replaced with concrete. My house is a genuine, traditionally constructed one, though.” Indeed, many of the homes did appear to be made of concrete with stones plastered on top.

While the village is now popular with tourists, it originally grew as a fishing village. Apparently the terraces in front of its houses were once used as spaces to dry nets. Today, many of them are used for café terrace seating instead.

-

The exterior of Wanghailou

-

Qinbi at dusk

The interior of this guesthouse was also a nested wooden structure. Unlike my previous day’s lodging, though, it was three stories high, and felt incredibly warm on the inside thanks to its inner wooden walls. Its window fittings were inward-opening wooden doors that could be fixed in place with latches resembling two small birds.

These windows on both sides of the stone walls narrowed as they went deeper, truly reminding me of gun ports. Such gun port windows were used in European strongholds and Japanese castles, minimizing their openings so as to defend from the outside while opening up on the inside to make them more convenient for attacking. The houses on Matsu really are reminiscent of military facilities. Of course, this window I saw was likely the result of a search for a way to maximize brightness with the smallest possible window.

-

A gun port-like window

The color and shape of Wanghailou’s stones seemed to be in better shape than the more handmade feel found in my previous day’s house, as though they were extracted in an intentional manner. It was as if I could smell the scent of mass production even within its vernacular style.

When I asked my host about this, he said that its stones came from Fujian, across the sea. The village fishermen would load up with fish and head out to trade, then reload their empty boats with lots of stones on the return voyage to prevent from capsizing.

Of course. What an utterly logical reason. Hearing this also made me think that the way houses are created is even more influenced by something like coincidence than I thought. Hearing these words also made me imagine the time when this remote Taiwanese island had deep ties with the continent. These walls built by the people of that age had looked out at the ocean for over a century.

I squinted and looked across the ocean to find multiple black ships floating there. Behind them was land. When I zoomed my camera in as far as it could go and took a look, I found a sprawling city lined with tall buildings.

-

The city on the continent

(Continued in issue 6)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window“). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024