Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Final Issue: Asia, Traveled through a Window

07 Jul 2021

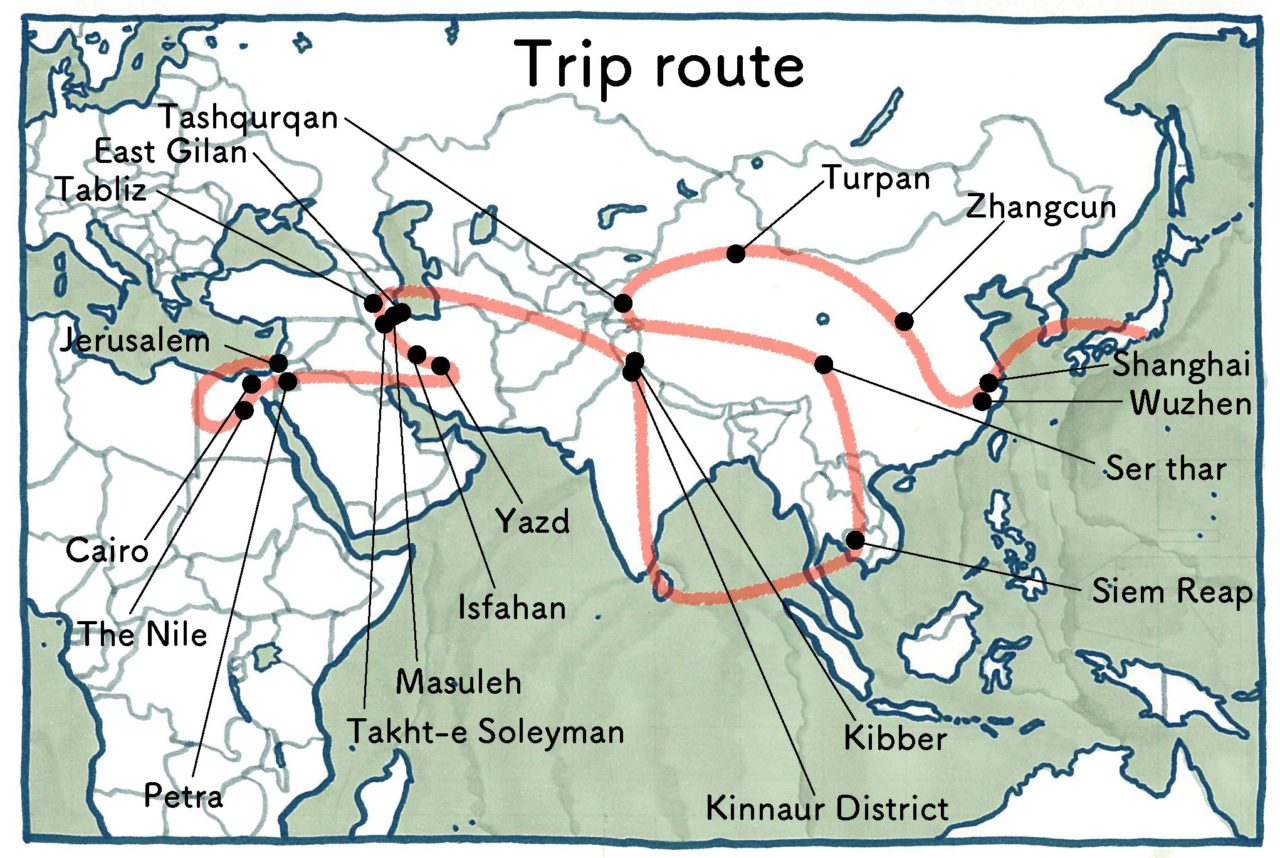

This will be the final installment of my four-year-long serialization documenting my eight-month-long trip. While I had decided where to go ahead of time to some degree, there was still some freedom to my journey. I would change my plans if I discovered somewhere that looked interesting, and I decided where I would stay once I arrived in a city, for example. I visited ruins and tourist destinations, but I also made efforts to go see homes belonging to regular people. With little information about rural villages, I found and visited locations that intuitively interested me using maps and aerial photographs, and that is why so many of the structures I introduced in this series were ones I discovered by chance. When I first began on these essays, my plan was to write about each separate location and its windows. As I continued writing, though, I found windows that resembled others I’d seen in distant lands and noticed the way that various architectural components manifested themselves based on similar principles, leading to new articles containing links tied to past entries.

For example, the homes in Turpan, located in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, use bricks stacked at the top parts of their walls to create openings, and their roofs are built from there out to a yard. This method that I called a “lifted roof” could also be described as one architectural method of protecting bodies from harsh natural conditions and allowing for “breathing,” like what I saw in the openings in towers connected to underground water channels, courtyards, and cisterns located in Iran’s Yazd, another city in the desert. It could also be described as a convention of Islamic city planning born from the consideration given to privacy, as I saw in Isfahan, also in Iran. Then, when I went to Cairo, Egypt, I encountered the roofs of Turpan’s homes expanded to a city-sized scale in a bazaar there. These were all similarities I noticed after the fact as I wrote my essays.

-

Turpan’s “lifted roofs”

-

Yazd’s “breathing” openings

-

The roof of Cairo’s al-Ghuri Complex, a mixed-use facility.

A “lifted roof” on a city-sized scale.

In the “overhanging village” in India’s Kinnaur district, I was struck by the contrast between the small windows located in heavy walls made of alternating layers of rock and Himalayan cedar and the free, large windows in the wooden sections overhanging them. It seemed that the knowledge of how to simultaneously have a dark and warm space alongside a bright and open one is important in one’s life.

For example, the homes “placed” on top of the ground in Iran’s East Gilan were created to have rooms with few windows to deal with cold winters that are then surrounded by semi-outdoor areas. This also reminded me of Japanese architecture. Thinking about it now, the way the people of Turpan would stay in their brick homes during the winter but sleep in their large courtyard beds in the summer made it as if the two spaces acted as independent homes, one for the summer and one for the winter. The difference in temperature throughout a year had split their homes in two.

Furthermore, while likely created due to recent standards of hygiene and changes in public safety, the old stone houses of Jerusalem’s Old City with verandas attached to them could also be called structures with “dark and warm spaces” alongside “bright and open spaces.” It’s very interesting to know that similar sights had come into existence in a holy city and a rural Indian village.

-

The small wall windows and large overhanging windows of Bhimakali Temple in Kinnaur district

-

A home in East Gilan. A bright veranda area surrounds a core with few windows.

-

A courtyard surrounded by sturdy bricks is used as a summer home (Turpan)

On the other hand, there were many times when I realized that windows existed independent of a structure as I looked at them. In Masuleh, Iran, the age of the village and its structures resulted in windows and buildings being renewed at “shifted” points in time. Windows from various timelines co-existed there, creating a rich and full sight. One could say that the age of the village had manifested itself in the diversity of its windows.

In villages with little lumber in the area, windows themselves are a singularity that allow outside cultures in. Larung Gar in eastern Tibet is a modern example. The countless aluminum sash windows glimmering inside the monks’ self-built log cabins was a striking sight. On the other hand, there was the first home in Wuzhen, China I was allowed into near the beginning of my journey, a small and newly developed house created outside of a scenic district during its development as a tourist destination. An old wooden door had been brought inside of it, something that could be called “shifted” in a similar manner to what I saw in Masuleh. Architectural structures may change, but old customs and moods remain in the areas around their windows.

-

The sight of many windows from “shifted” timelines coexisting (Masuleh)

-

Aluminum sash windows lined up in the homes of monks (Larung Gar)

-

An old wooden door brought into a newly developed house (Wuzhen)

I think there was meaning in my writing these essays on windows as I traveled Asia because doing so allowed me to connect locations that are physically separated. The people of these lands, thousands of kilometers apart, would never have seen each other’s faces. It seems to me that the fact these strangers in separate places still create similar structures is not only because they are responding to specific climate conditions, but also because of certain “habits” shared by people when we approach land and culture. There must have been certain ways of doing things that were first shared with neighbors before slowly but steadily spreading to other villages and countries. It’s these kinds of methods invented by many people that are whittled down into universal “habits” that remain with us.

Though I began writing these essays with the intention of introducing the diversity of windows, when I looked at Asia through windows, I found that while it is not a monolith, it isn’t as disparate as one might think.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.