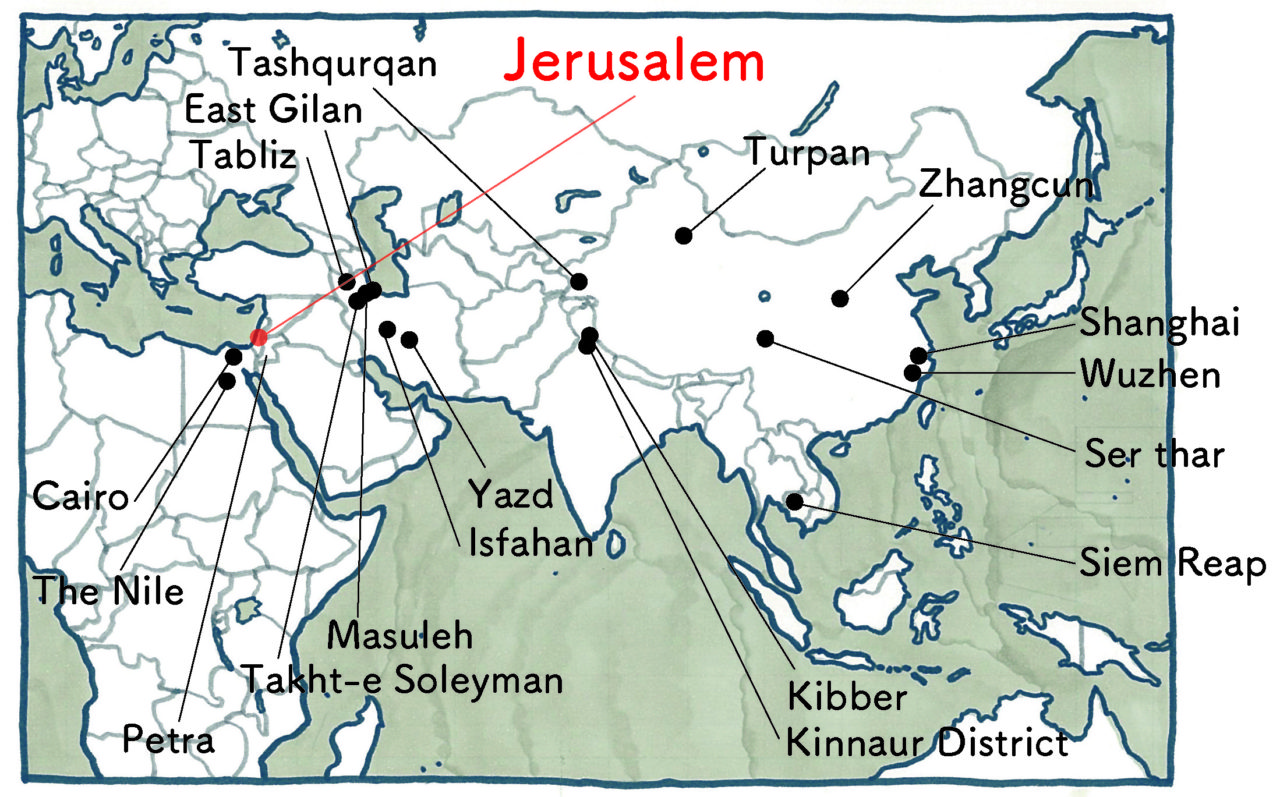

Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Life in the Holy Land: Jerusalem, Israel

22 Mar 2021

I could see land the color of milk out of the airplane window. My journey had started in China, moving ever westward from there, and I was now on a short flight from Egypt headed to my final destination, Israel.

Nearly the moment I landed at the airport, I underwent a three-hour-long background check. Perhaps my appearance roused their suspicions? I hadn’t experienced an episode like this at immigration in any other country, and it spoke volumes about the tension in Israel’s air. This tension, of course, is due to the existence of Jerusalem, a holy land. The sole reason I had come to this country was to see this city that could be called the center of faith in the Western world.

I went from the Mediterranean Sea-facing capital of Tel Aviv, lined by skyscrapers sitting on alluvium, and headed about an hour eastward. As I traveled from the airport, before me past the car window was that same vast white expanse of land I saw from the sky. These hills were all limestone, and atop them was Jerusalem.

-

Israel as seen from the airplane

Within this modern metropolis where trams run is a region surrounded by heavy stone ramparts. This is Jerusalem’s Old City. Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Armenians continue to live here in divided districts, while pilgrims from abroad are found everywhere you look. Markets, souvenir shops, holy sites, and temple ruins bustle within the walls. Most of its structures, its walls included, seem to be made from the same limestone the city is built upon. The center of the world was the color of milk.

-

A path in the Old City

For example, the Jewish holy site of the Wailing Wall is a wall from the Temple in Jerusalem originally built in 20 BCE, and it consists of limestone that has been piled up over the course of around 2,000 years. As I approached it, I noticed Jewish believers in black clothes sticking pieces of paper with words written on them between the stones, then putting their hands to the wall and praying. Their prayers felt to me like something I could spend a lifetime trying and failing to understand.

-

The Wailing Wall

There are other spaces that have been created by digging into limestone, such as the underground shrine at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre that is said to be the tomb of Jesus.

The Dome of the Rock, an Islamic holy site, is said to be the place where Muhammad ascended to heaven. Its exterior, consisting of blue tiles and colorful pillars, may appear at first to have nothing to do with limestone, but in fact this is a structure built to protect the sacred rock found inside the dome. Unfortunately, I have to rely on photographs to see the details as only those of the faith may enter inside, but it seems that at the top of the hill is an enshrined segment of limestone jutting strangely out from the ground. In other words, this holy site has its roots in the discovery of a special rock.

-

The Dome of the Rock from afar

It is in this way that Jerusalem’s holy sites are all formed by limestone. Perhaps at the foundation of this was something like the rock-based faith I saw in the ruins of Petra that existed before any modern religion. It almost seemed as though this milk-colored hill itself was something of an Old Testament that these three religions were built upon.

This is of course a thought from someone who holds no faith at all, but living beside those of faiths different from one’s own cannot be too peaceful of a thing. Most of the structures in the city had barred openings, and strict crime prevention measures were in place. This was strange to see as a Japanese person, but perhaps this is the regular state of a metropolis. I even saw a barred window in the Jewish Quarter that took as a motif a Menorah, an icon of Judaism, built to match a stone arch.

-

A window designed like a Menorah, an icon of Judaism

As for the people of the Old City, they live in stone structures that seem to have stood there for centuries, much like its holy sites. Stones may be sturdy, but that also makes them difficult to move. Given that the people of the Old City live lives every bit as modern as our own, they must experience many inconveniences there.

Looking down from a high location, I could see some poignant elements of life in this city in the various additions located on the rear of its stone buildings.

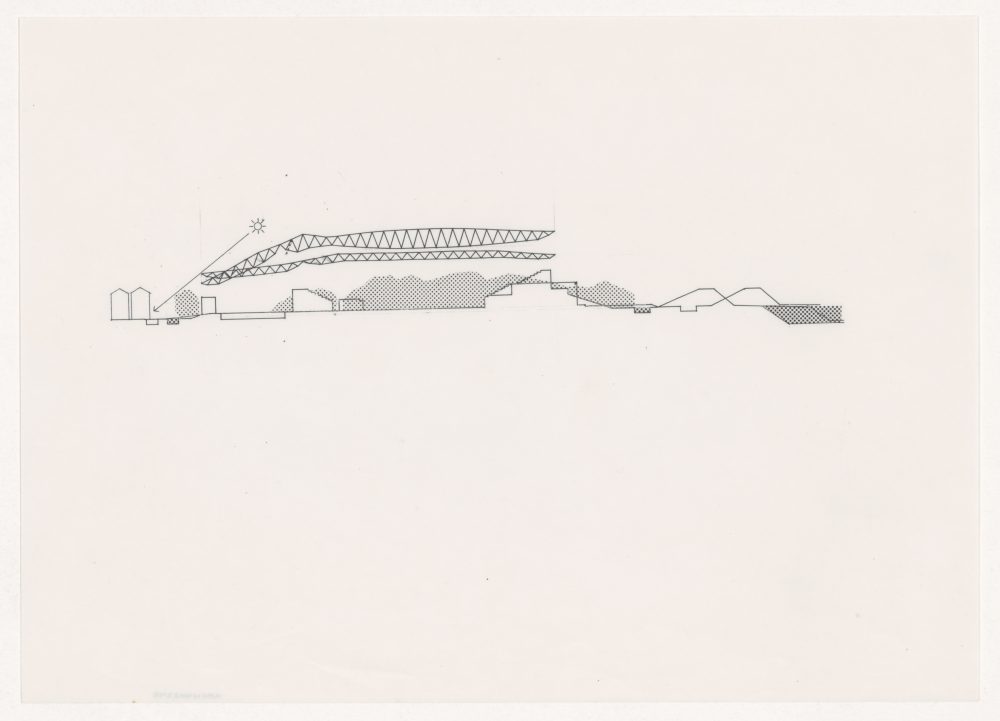

Verandas jutting out from buildings are one such example. There must have not been enough space to hang laundry in these old structures, but even those living on holy ground would at least want to dry their clothes outside or have a place to drink tea. As bright, semi-outdoor spaces made necessary by their main structure’s gravity and lack of windows, they share something in common with the homes of Iran’s East Gilan or India’s overhanging homes.

Examining these windows even further, I saw many former arch-shaped openings that had been filled in and replaced by square windows. The simplicity of ready-made windows changed the expression of these buildings.

-

Looking down at the backs of buildings in the Old City

I could see a mix of both pitched and flat roofs, with strange protrusions popping out all over the flat ones. I could never figure out what exactly they were, but it could be that their interiors are either dome-shaped, or that the shapes are used for drainage. Next to these protrusions were many antennas and solar energy water heaters. Modern infrastructure relentlessly demanded space even in this Old City that consists of historic structures.

-

An addition that seems to be a bathroom jutting out from the building

When I walked around the city, I couldn’t believe how many additions I found jutting out of stone structures. I think that these internalized protruding spaces dotted with small windows are meant for wet areas such as toilets and baths. Ready-made windows were fitted firmly into these additions, creating an interesting contrast with the first-floor window frames built in openings from the outside. It was another sight to see in Jerusalem, a city that grapples with the inconveniences of historical buildings.

-

Homes with jutting additions seen past the walls of the Old City

At the core of this milk-colored world are its rocks, and their immovability is what has protected it until the present day. It also seems that their immovability creates hardship for its residents.

However, in the way that this land’s people have created protrusions to do whatever they can to improve their lives in these hard-to-move stone structures, we can see their lives in a shape that transcends religion. It was in this worldliness I found in Jerusalem that I felt I could see the city trying to survive, just as its people have for millennia.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.