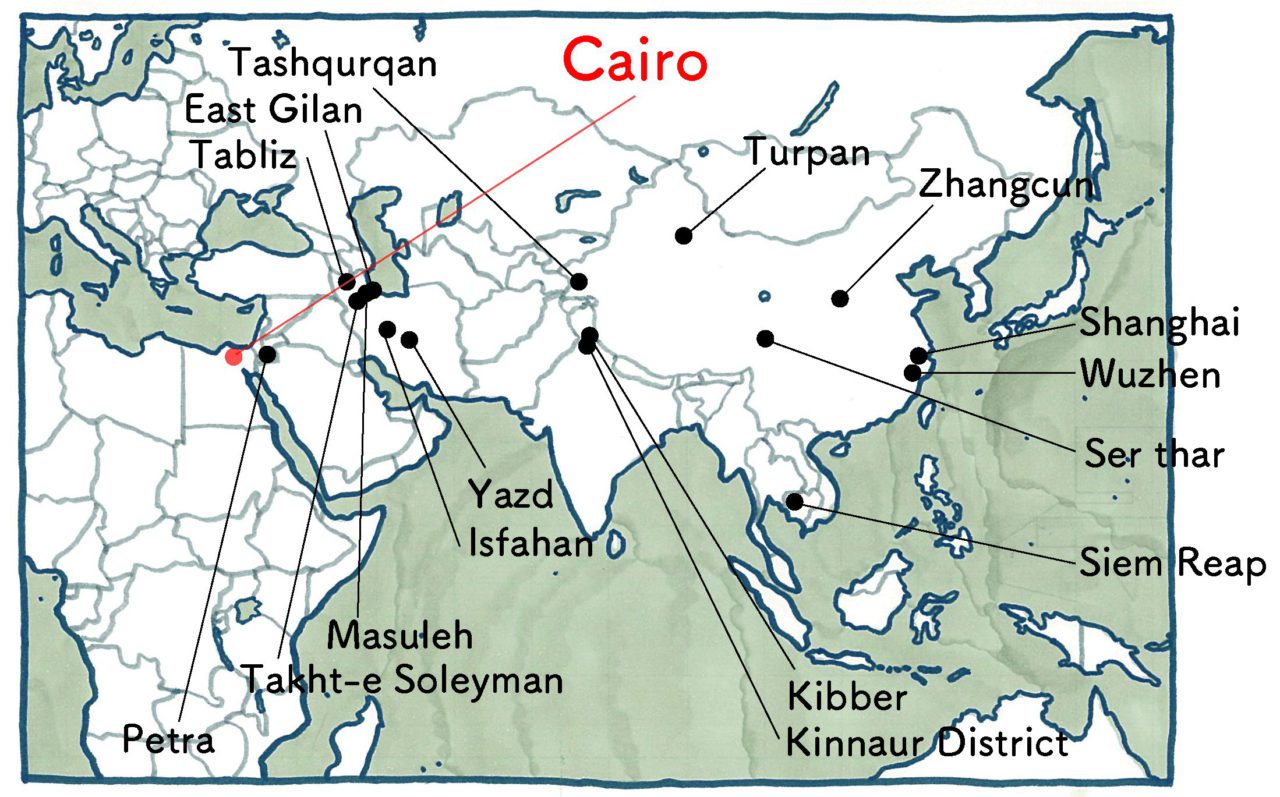

Series Traveling Asia through a Window

A Combining City: Cairo

15 Jul 2020

I got on a plane in Jordan and flew to Cairo, Egypt. It was my first time on the African continent. Though most capitals are busy, Cairo seemed especially so. Just walking from my hotel out into the street was a struggle. The endless number of cars never stopped blaring their horns, and I was nearly run over multiple times. What incredible energy.

Cairo is a major metropolis with a population of 20 million located at the base of the Nile Delta, where the river begins to flow into the Mediterranean sea. Modern-day Cairo was originally the city of al-Qāhirah, built by the 10th century Fatimid Caliphate, and it exists to this day as “Islamic Cairo,” an area with a concentration of historic Islamic architecture that is also a tourist destination.

Islamic Cairo, where people have lived and left their mark for over a thousand years, has many homes, markets, and mosques, and it continues to be in full use to this day.

-

The streets of Islamic Cairo

When I climbed Bab Zuwayla, one of the gates in the region that still stands to this day, to look down on its streets, I saw before me a number of mosques’ minarets (towers) as well as thin, sprawling streets. Many of the buildings were about three or four stories tall, and for whatever reason, there was a mess on top of each of their roofs. Could it have been abandoned garbage from when they were expanded? Car traffic seemed to be prohibited on the streets, and the police rode on horses rather than in cars.

I continued wandering around aimlessly and ate a cheap and delicious lunch. Then, as I walked through the city, occasionally peeking into buildings such as hookah establishments, I found what looked to be an old stone building on a block corner.

-

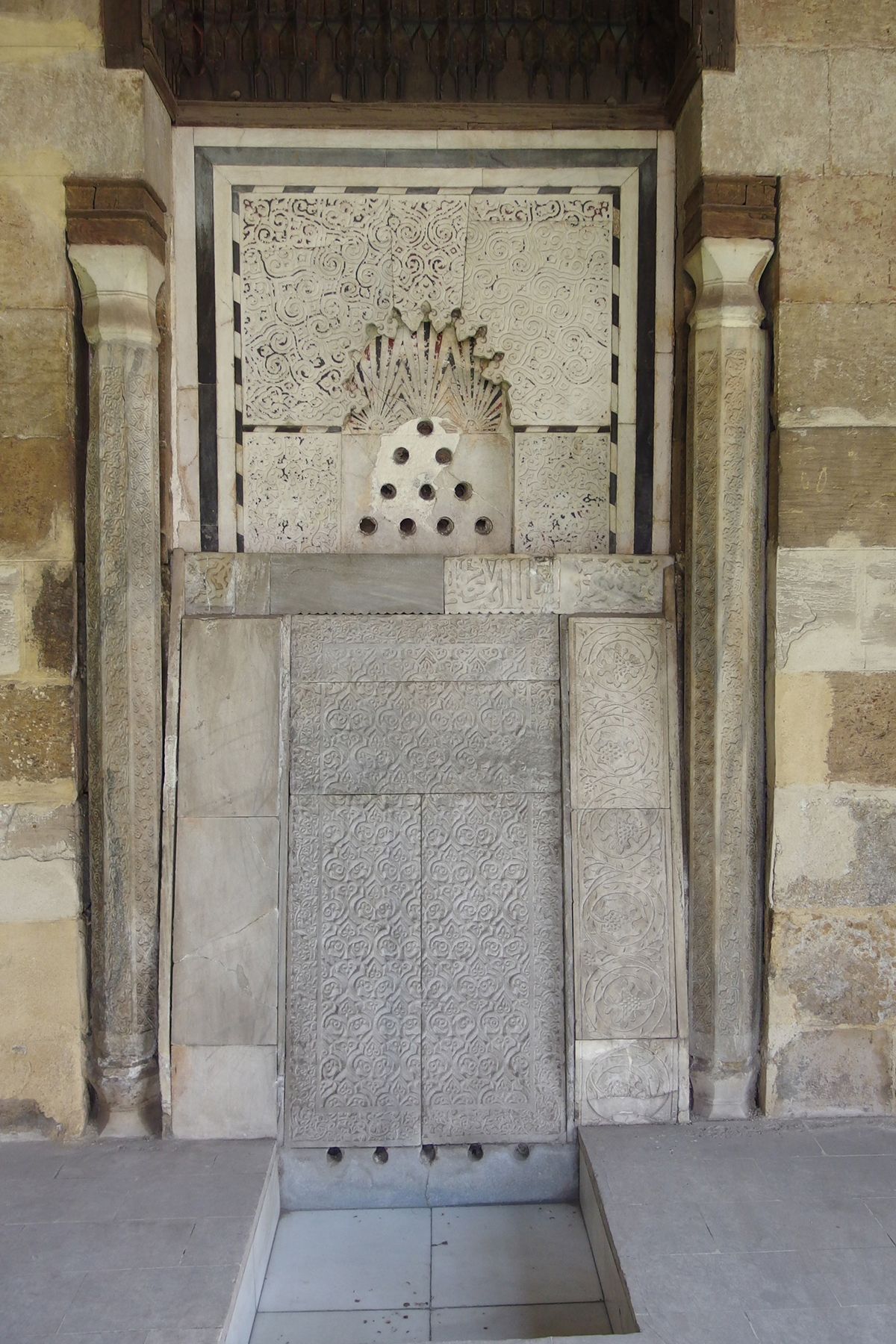

The sabil-kuttab on the block corner

The structure had a large jail-like latticed entrance on its first floor, while a delicately made wooden terrace and roof had been added to its second floor. Looking into it, the building was a public structure known as a sabil-kuttab, a combination of a first-floor water fountain (sabil) and a second-floor religious school (kuttab). This combination of functions struck me as odd, but indeed, both water and education are necessities. These were apparently quite widespread public spaces in Cairo, with as many as 300 existing in the 19th century.

The water fountain on the first floor apparently distributed water for free to residents through its bars. There were apparently water dispensing men there to make sure that no one walked off with the valuable water carried there from the Nile. Given that it was made to protect water, you could say that it was like the opposite of a prison.

-

The circular water fountain (sabil). Its eaves are unique.

One sabil-kuttab was open, so I went inside. It was designed so that the water pulled up from its underground reservoir would then fall from a stone slab with ornamental carvings. From here, the aerated water (a method of water purification) was scooped up and distributed. It was a highly advanced and beautiful piece of infrastructure. In every function, I could see the Islamic sensibility that attempts to impart beauty.

-

Water flows through the stone slab below the spout

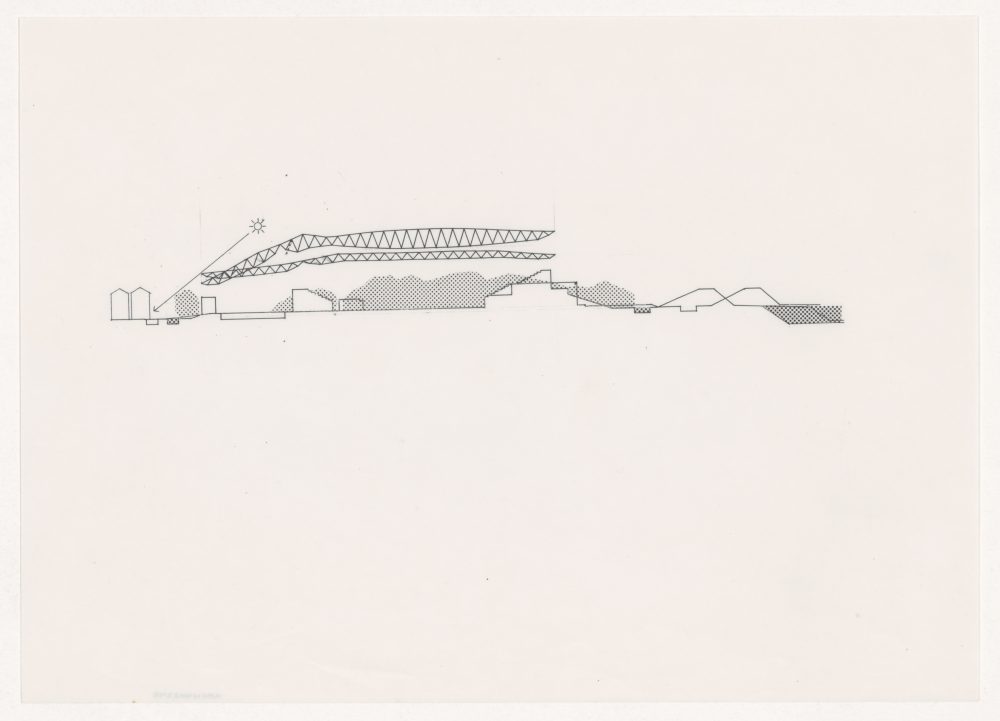

I then walked through the main drag and into its principal street, only to encounter a massive wooden roof covering the path.

This horizontal wood roof supported by wooden (diagonal) braces sticking out from the buildings blocks out sunlight, and there is also a large square hole in its center. Street vendors gather around its shade while shoppers are spread about everywhere. Upon closer inspection, I could see small spaces between the roof and the buildings, reminding me of the “lifted roofs” of homes in Turpan, China.

-

The al-Ghuri Complex, packed with shoppers, as seen from below.

-

A roof lifted off a building. The windows feature intricate designs.

This facility consisting of two buildings that face each other on opposite sides of the street is known as the al-Ghuri Complex. It is a mixed-use facility that combines a mosque, a mausoleum, a previously mentioned sabil-kuttab, and more, and it was built in the early 16th century.

The buildings consist of alternating red and white stones piled atop one another, appearing to be not structures designed as monuments but rather ones that came about in an ad-hoc way, following along with the street. Their windows have various designs, and your eyes are drawn to the glass windows set in wood just inside their double arches as well as their intricacy that contrasts with the massive, powerful roof.

These detailed designs continue even inside the buildings. After passing first through the courtyard that light pours into, then the massive, impressive arch inscribed with Arabic characters, you arrive at a small, dimly lit prayer room. On the upper part of the wall is colorful stained glass, as well as mashrabiyas and latticed windows, each with their own purpose but still brought together in a way that does not make them seem too separate from one another.

-

The al-Ghuri Complex’s small prayer room

As worshipping idols is prohibited in Islam, the religion has never had the concept of building mausoleums to enshrine saints. Part of the history of this mixed-use building in Islamic Cairo is that it combined other facilities together with a mausoleum, a structure that does not fit with traditional Islamic teachings, in hopes of making it more accepted by residents as a public facility. This tradition of combination, as seen the Sabil-kuttab and the al-Ghuri Complex, may have come about in the process of Islamic architecture being opened to the people. As they did not take authoritarian forms, they continue to be used as a natural part of life there, and even if by chance, this must connect to the preservation of the diversity of windows found there.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.