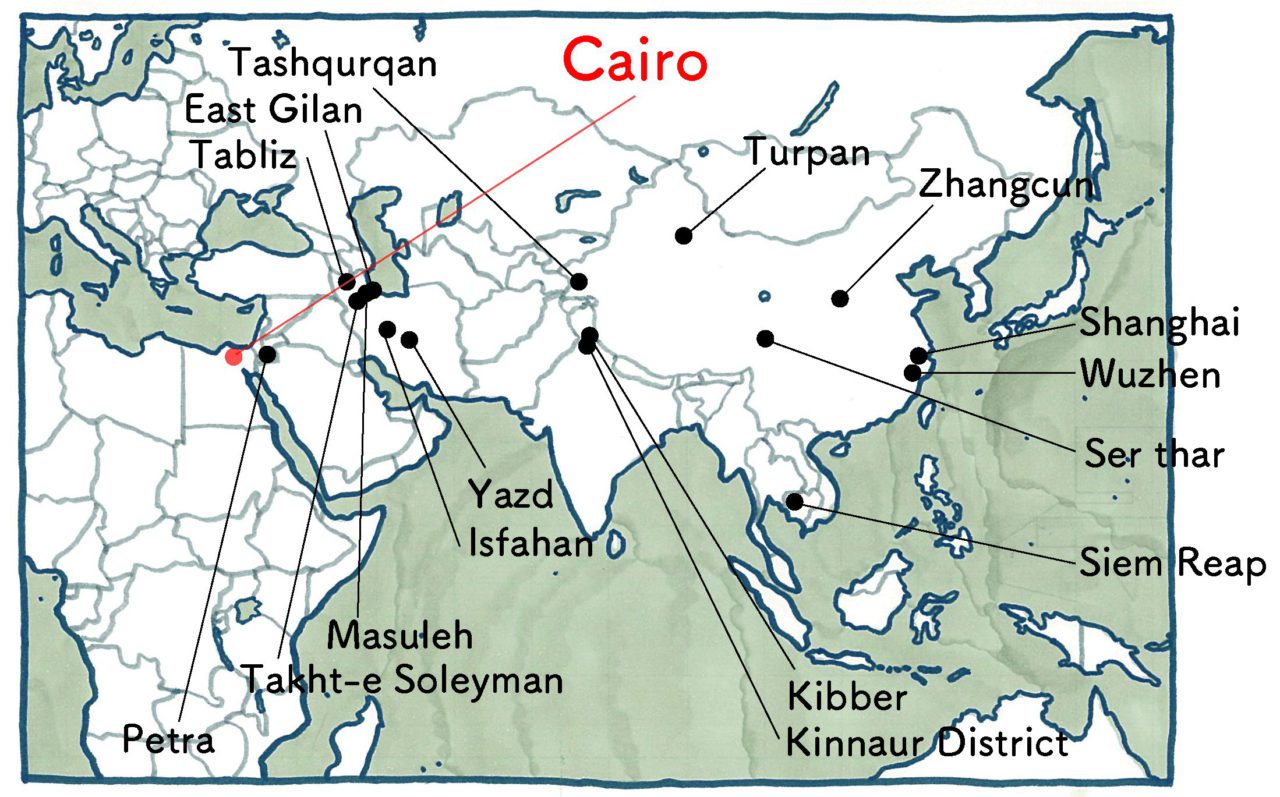

Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Facing the Arches: Cairo, Egypt (part 2)

15 Sep 2020

Before Al-Qahirah, the city that would become Cairo, was created in the 10th century, the city of Fustat stood slightly to the south. In this region now known as Old Cairo is the oldest mosque on the continent of Africa, the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As. This mosque has its origins in the 7th century, a time when Islam first began to spread throughout the world. This article is a record of what I saw of this mosque that has undergone countless extensions and reconstructions during the course of over 1,300 years.

That said, the mosque is fortunately open to just about anyone. There had been mosques in all the Islamic cities I had visited so far, and I could hear the adhan (call to prayer) from anywhere within them. There were many times when I took a peek inside mosques having been drawn in by such voices. Though many Japanese people feel few to no ties to mosques, I personally find them far more inviting than Christian churches.

When entering a mosque, you first wash your feet. You also wash from your hands to your upper arms, as well as your face, neck, and ears carefully. It is a basic principle that you pray with a cleansed body. As this is done multiple times a day, some think that Muslims are quite fastidious people (and when I think about it, all of the Muslim homes I entered were clean as well). Once tidy, you take off your shoes in the carpeted worship area and enter inside. This must be one of the reasons that I find mosques so pleasant as a Japanese person.

-

The exterior of the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As

The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As is a massive 120-by-110-meter mosque surrounded by thick, rampart-like, milk-colored walls. Inside is a forest-like space with about 150 regularly spaced white stone pillars surrounding a courtyard. This layout is sometimes called an Arabic type mosque and is similar to the Prophet’s Mosque, the archetype for future mosques that was built by Muhammad himself (said to be a simple space consisting of a colonnade of trees and a courtyard).

As Islam was a religion that spread quickly in its early days along with an army, mosques were more often built making good use of past sites in various locations rather than according to any one architectural style. It’s said that the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As grew as stone pillars taken from Roman and other classical architecture were combined together until it reached its current form in the 9th century.

We often see such materials from classical architecture used in Egypt. One could say that what makes early Islamic architecture so interesting is these signs of use of a bricolage of materials and techniques to secure enough space to accommodate the rapidly growing number of Muslims. For example, in Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque, we see signs of mismatched stone columns lined up next to one another whose heights were later adjusted. It is this kind of Islamic sensibility that led to the use of massive stone pillars from the age of the Pharaohs with sections cut out of them to create mihrabs (niches indicating the direction for prayer.)

-

Mismatched columns from antiquity whose heights have been adjusted (Al-Azhar Mosque)

-

Using stone pillars from the time of the pharaohs as a mihrab (A mosque in Luxor)

The sun was still high when I arrived at the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, and afternoon prayers had yet to begin. Inside the mosque were people up against pillars reading books, elderly individuals laid out on the carpet napping, and children simply running around. No one seemed to pay any particular mind to this traveler from another country as they all spent their afternoon in this open area. I couldn’t help but feel jealous of this open time they had in their lives. There is nothing in the way in the courtyard and the prayer hall, only endless lines of pillars.

-

Early afternoon in a space that is neither inside nor outside

Arches are built across the top sections of the pillars, with thin wooden roof beams found above their capitals keeping them from expanding. Above the arches is a level wooden roof. This pillar-filled space is the leading element of the mosque’s structure, but it can all also be called a type of window or aperture. As these so-called “windows” stretch in every direction, they overlap in many different ways depending on the angle they are seen from, and level planes that should look orderly can appear discontinuous and separated.

The top sections of the tall and closed-off outer walls are open windows with detailed mashrabiyas. These must exist so that hot air can exit from them, leaving only a pleasant breeze in the courtyard.

-

Men sitting against pillars as they read the Quran

As the adhan reverberated throughout the mosque, the old men laying on the ground rose up to join the line of men who entered one after another. As it wasn’t as if I could join them in prayer, I watched from the back, slightly nervous. When I faced the arches as they did, the prayer hall filled with such tension that it seemed as though the early afternoon scene from moments earlier had vanished into thin air.

-

Individuals lined up to worship as they face the arches

The sight of these grown men in a line was a slightly odd one to me. In my own experience, I had only ever lined up in such a way during gym class or to take group photos. Yet the practice of all of these men lining up in a mosque formed a space that was long yet shallow completely unlike what one experiences in a church (where arches draw you inward in order to emphasize depths, in contrast).

Though it’s said this originates in the way that desert nomads traveled in a side-to-side line, there is also a sense of commonality with others created when everyone faces the same direction. The attraction I felt toward Mosques that even seemed like a kind of admiration can be summed up by this sense of sharing something with others. The sideways succession of arches (windows) here must have instinctively indicated to people the direction for prayer ever since the 7th century.

-

An elderly man sleeping on a carpet among the many arches

When I happened to look at their feet, I saw a succession of small arches even there on the carpet. It was as if they each had a personal prayer space. These arches that came forth as a result of a need to connect pillars together had at some point become icons that indicated the direction for prayer, to the point that they had even been sewn into the carpet.

There was no way that the old man who continued to sleep through prayers could have considered this as I had. I decided to leave the mosque quietly, so as not to bother his rest.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.