Chapter 1: The studio – exploring the mind of the artist from Caspar David Friedrich to Spencer Finch

26 Apr 2019

An artist contemplates a blank canvas or a white piece of paper in the studio or at a table, perhaps waiting for a memory or some inspiration to stimulate that first mark. What follows is an insight into either their viewpoint of the world or the inner workings of the artist’s mind at that moment. Either way or whatever the impetus behind that initial gesture, the pristine surface and the bounds of the blank support are there to be broken through, in order to begin creating a window to another reality.

The rectilinear frame of a painting mimics that of a window, waiting to be filled in or opened up. The two-dimensional panel can be seen as an aperture to escape from or to burrow into and hide, while the lack of transparent panes of glass means both artist and viewer are required to insert or intuit their own vision of what lies on or behind the picture plane.

While the myth of the artist as a lonesome author struggling to express desires, knowledge or experience while trapped within the confines of the studio was long ago dispelled by the complication of assistants, patrons, mentors, judgments or all manners of other external pressures, the act of reaching beyond the consciousness or immediate purview of the artist is surely an attempt to unlock the transcendental nature of art. A window then is not only of a similar shape to the canvas but is a metaphor for how the act of making art is also one of leaving behind the immediacy of what is at hand in the studio and pushing through to an understanding of what else might be possible.

The studio was traditionally the site of production and the base camp of inspiration, but rarely were the insides of a painter’s garret or study of enduring interest to anyone but the poor soul cast adrift therein. Instead, the depictions of studios in art history are themselves glimpses through personal windows that similarly mirror the unboxing of the self and the need to break out of the familiar. Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study (circa 1745, National Gallery, London) recognises this dichotomy – between the interior life of this scholarly, monkish figure, keenly lost in his philosophical books, and the joys and dangers of the real world outside, represented by the views of mountains, rivers and white towers through the chapel windows on the left and by the shadowy figure of a lion, encroaching on Jerome’s meditative space to his right (the story goes that the saint attended to the limping creature by removing a thorn from its paw).

-

Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study, circa 1745, National Gallery, London

If this environment seems staged and structured, then the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich tend towards the wild and untamed, showing solitary human figures, seen from behind, as they stare out into the abyss of various epic landscapes in awe at the majesty of nature and their insignificant place within this panorama. Although the central figure of one of his more reserved paintings, Woman at a Window (1822, AlteNationalgalerie, Berlin), strikes the same pensive pose, she is visually hemmed in by the rigid architecture of the studio’s shutters. We see Friedrich’s wife, Caroline leaning out of the studio window to stare at the river Elbe in Dresden below, although we cannot see her view or quite gauge her mood.

-

Caspar David Friedrich, Woman at a Window, 1822, Altenationalgalerie, Berlin

Instead, we indulge in a fantasy of empathy with this figure, much as we do when people watching from our own vantage point through a train window or from the safe distance of a café interior. Her relative lack of perspective through this narrow enclosure suggests that, like us, this lonely figure yearns for a closer look at the vista she surveys and a modicum of the freedom required to travel beyond those walls.

-

Caspar David Friedrich, View from the Artist’s Studio, Window on the Right, 1805, Belvedere, Vienna

-

Caspar David Friedrich, View from the Artist’s Studio, Window on the Left, 1805, Belvedere, Vienna

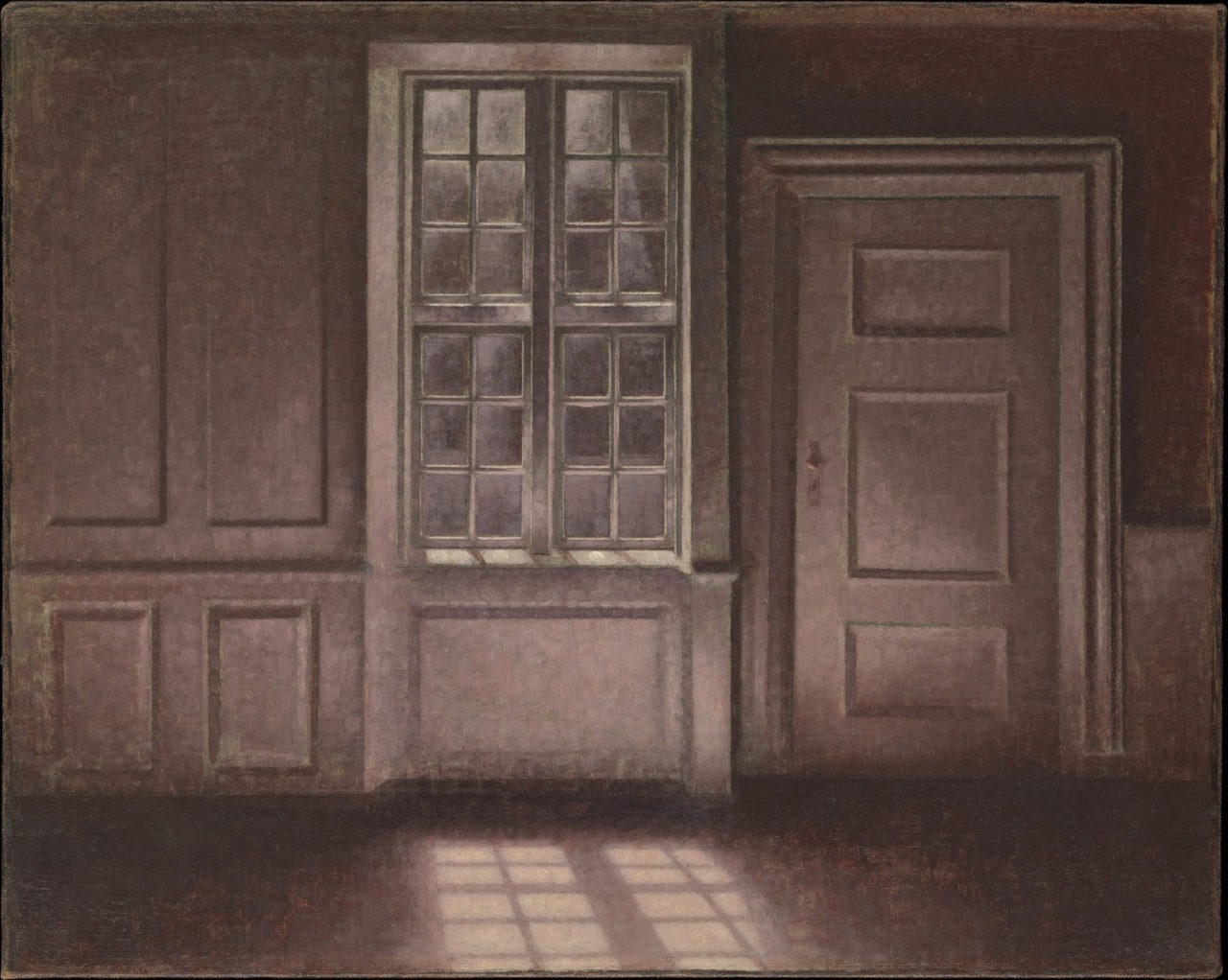

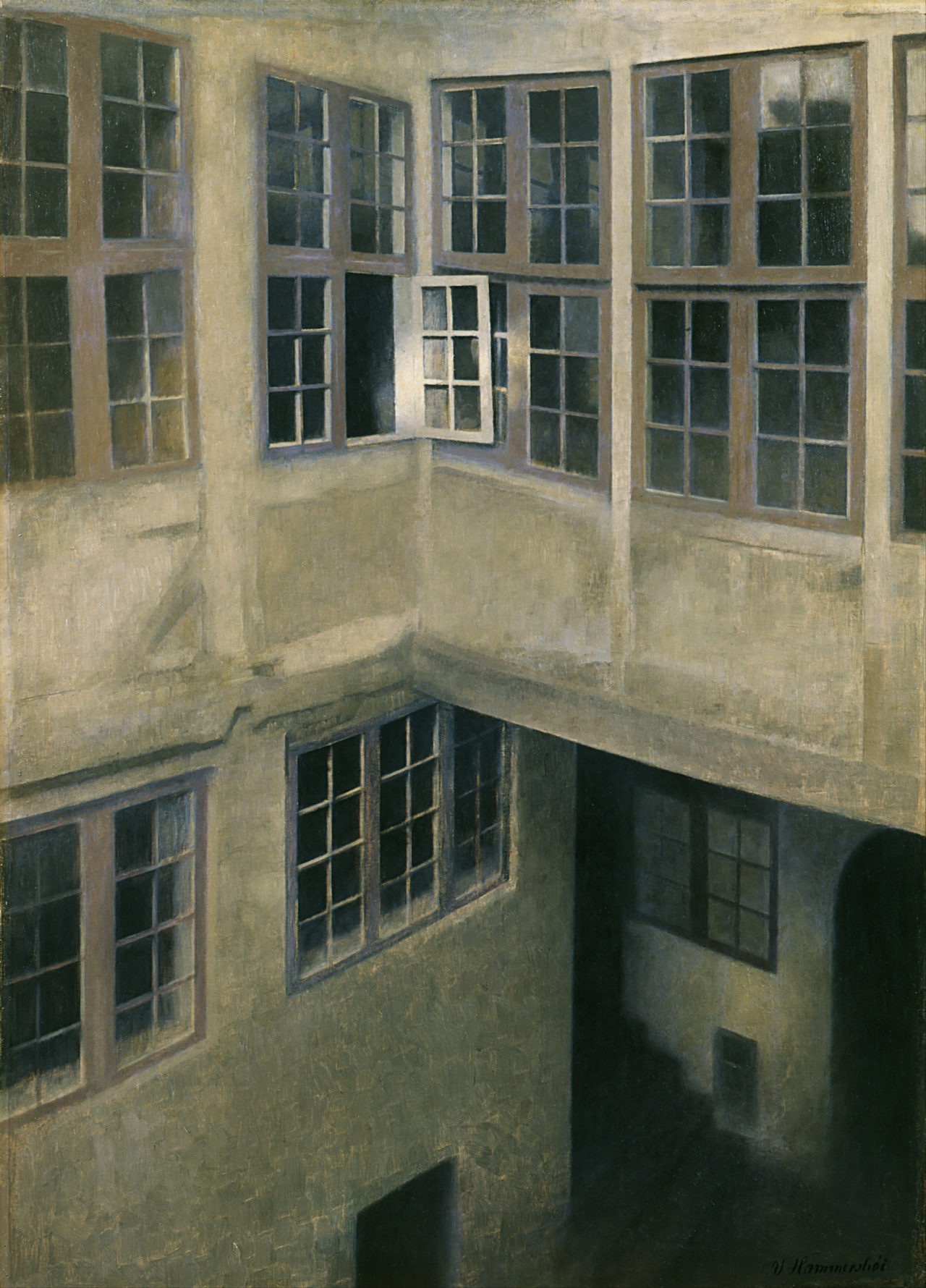

An even more claustrophobic image comes from one of many paintings by Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi of the apartment and studio where he lived with his wife from 1898 to 1909 in Christianshavn. His Interior of Courtyard, Strandgarde 30 (1899, Toledo Museum of Art) multiplies the windows seen in his other depictions of his spartan surroundings, to an extreme of lines and grids with seemingly nothing but empty space inhabiting each glass square. As in Friedrich’s image of buttoned-up domesticity, the chink of light here comes through the only open window, offering a release from the oppressive interiority suggested by the almost monochrome palette of colours and the relentless crisscrossing concealment of the window panes.

-

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Moonlight, Strandgade 30, 1900–1906, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior of Courtyard, Strandgarde 30, 1899, Toledo Museum of Art

A brighter, green and ochre colour scheme, redolent of the south of France, infuses Vincent van Gogh’s hazy Window in the Studio (1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), yet the windows themselves are barred shut, revealing the artist’s period of voluntary confinement within the insane asylum at Saint-Paul-De-Mausole. This picture of his studio-cum-cell was painted barely a year after Van Gogh’s brutal self-mutilation in 1888, when he cut much of his left ear off after an argument with the visiting Paul Gauguin. His time incarcerated and in convalescence was surprisingly productive, however, both in terms of paintings produced within the grounds of the institution and time spent planning future works he would produce when back home at the Yellow House in Arles. While his bedroom’s location in the east wing of the men’s block was isolating, his studio was in the north block with views and access to the pretty garden that became the subject of many works of this period. Still, the prison-like bars block out the most vivid colours of the outside world, also rendering everything inside in more muted tones and indeterminate form, with see-through bottles and brush pots seemingly hovering on the edge of existence, painted in oil paint watered down to near vanishing point.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Window in the Studio, 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

A century or so on and we are said to be in a ʻpost-studio’ era of art making, in which increasingly hands-off artists use only laptops and phones to control their vision, needing neither a dedicated studio nor a physical outcome to help realise their final expressions of interior thought. In this post-medium, post-modern and post-everything age, the deconstruction of the work of art means that the studio has also become a diffuse, less certain component in an artist’s set of tools. The traditional studios of artists such as Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi, Alberto Giacometti, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore are now preserved in aspic for visitors to gawp into, rather than for anyone to look outwards from.

Whether it was Francis Bacon’s claustrophobic, windowless, detritus-filled room at 7 Reece Mews in South Kensington; Lucian Freud’s shuttered, private space; Howard Hodgkin’s top light atelier or Jackson Pollock’s vast upstate barn, it seems as if artists of the 20th century increasingly had no need for windows to the outside world – there was no need to look outwardly for inspiration, no need for figuration, for experiencing the atmosphere or to observe delicate shifts in light or the scudding passage of a cloud.

Except, this is what the American artist Spencer Finch specialises in – the documentation of passing phenomena such as weather conditions, seasons, temperatures, the positions of the stars or times of the day. If he is an artist who can often be found staring out of a window, this is because he has also created vast and numerous works dedicated to this most wistful way of whiling away the hours of boredom, contemplation and inactivity spent in between the moments of actually making work.

For example, Finch has installed a giant glazed canopy entitled A Cloud Index (2013-19) above Paddington Station in London, which is made up of 200 transparent panels on which are etched his accurate drawings of every kind of cloud visible in the British Isles. Similarly for The River That Flows Both Ways (2009), Finch transformed an existing series of windows on The High Line in New York with 700 individual panes of glass, each coloured according to the water conditions as measured on the Hudson River over a period of 700 minutes in a single day. The work, like the river, is experienced differently depending on the light levels and atmospheric conditions of the day and time.

-

Spencer Finch, A Cloud Index, 2013-19, artist’s impression of canopy over Paddington Station

-

Spencer Finch, A Cloud Index, 2016 (pastel detail), Lisson Gallery, London

-

Spencer Finch, The River That Flows Both Ways, 2009, The High Line, New York

Finch’s more domestically scaled Light in an Empty Room (Studio at Night) (2015), is an installation that meticulously re-creates the subtle play of light and shadow projected through the windows of the artist’s studio onto the walls at night. A series of motorised components, suspended LED lights, and tracking lamps simulate the traffic lights, amber streetlights and car headlamps that traversed his Brooklyn studio on a given evening. Some 35 different lights are employed at the same angles and heights perceived through the windows of the studio, facsimiles of which have also been reproduced. The public are able to walk into the studio space and perceive the six-minute loop of light effects, but can also walk ʻback stage’ to see the whirring motors and miniature lights standing in for the street furniture and the real cars circling the block.

-

Spencer Finch, Light in an Empty Room (Studio at Night), 2015, Lisson Gallery, London

-

Spencer Finch, Light in an Empty Room (Studio at Night), 2015, Lisson Gallery, London

Finch, like Friedrich or Van Gogh, has created an intimate, atmospheric window into the artist’s studio practice while inviting viewers to become active participants of the memory of that moment, rather than mere passive admirers.

Ossian Ward

Content Director at Lisson Gallery (London/New York/Shanghai) and a writer on contemporary art. As well as leading the gallery’s communications and publishing teams he was co-curator of the major off-site exhibition, ‘Everything at Once’ and editor of the gallery’s 50th anniversary book, ‘ARTIST | WORK | LISSON’ (both 2017). Until 2013, he was the chief art critic and Visual Arts Editor at Time Out London for over six years and has contributed to magazines such as Art in America, Art + Auction, World of Interiors, Esquire, The News Statesman and Wallpaper, as well as newspapers including the Evening Standard, The Guardian, the Observer, The Times and The Independent on Sunday. Formerly editor of ArtReview and the V&A Magazine, he has also worked at The Art Newspaper and edited a biennial publication, The Artists’ Yearbook, for Thames & Hudson from 2005-2010. His book, titled Ways of Looking: How to Experience Contemporary Art was published by Laurence King in 2014. A sequel, Look Again: How to Experience the Old Masters will be published by Thames & Hudson in 2019.