Does light stop within window panes? – Yuriko Kurimoto’s Window

11 May 2023

Since Kunié Sugiura wrote about windows in New York last time, let’s start this article on the topic of the American windows that were once in Nagoya.

Yamato Seimei Building (originally the Nagoya Japan Conscription Hall , it was built in 1939 by Yokogawa Construction and modeled after modern American office buildings, with seven floors above ground and two below, air-conditioning and heating, electric shutters, and an elevator) was located at the intersection of Hirokoji-dori and Honmachi-dori in Nagoya, and had a curved, minimally-decorated exterior, a large southward-facing entrance, and spacious corridors that reflected its scale. “It was America,” said one of the building’s former tenants. Since it was one of the only buildings left standing after most of central Nagoya was burned down during World War 2, after the war it was occupied by the US Army who had just seized the territory to the south, and they set up their headquarters there. The building that was a copy of an American office became a real American office, so to speak. When the requisition was lifted in 1956, the Japan Conscription Insurance , who had changed their name to Yamato Life Insurance Company at this point (a fateful name, given the history of the building), used the building for a long time until its demolition in 2004, its imposing dignity casting an unignorable shadow over the streets of Nagoya.

-

The building at the time of the US military occupation, 1946-47 (Photo by Robert V. Mosier).

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/10756455/1/166

The building no longer exists. But its windows remain.

From the late 1980s, there was a space on the sixth floor of this building called Stegosaurus Studio. The photographer Hiromu Narita used it as his workplace. The stark office space, with its un-Japanese high ceilings and large walls, was sometimes used as a venue for presenting contemporary art, with its north-facing and corridor-facing windows left as is. Unlike the so-called white cube, it was used almost exclusively for the presentation of new works, and the brusque personality of the space seemed to have a certain synergy with the artworks (I say “seemed” because by the time I became involved in art, the building no longer existed and there is no way of knowing what it looked like at the time aside from whatever photographs have survived). A place for the young and innovative, it showed artists such as Eiji Watanabe, Hiroshi Sugito, and Arika Someya, who even to this day remain associated with the area; and although apparently no matter when you went no one was ever there, it was quietly in operation until it disappeared in the early 1990s. And, as I scavenged through the space’s exhibition archives, I discovered that there was one artist who persistently drew upon the windows of this building in her works.

Yuriko Kurimoto was born in 1950 in Nishi-ku, Nagoya. She, like the building, is no longer in this world.

In the early 1970s, Kurimoto studied painting at the Nagoya Zokei Junior College of Art & Design (the predecessor of today’s Nagoya Zokei University), but at the time when she was studying painting, the minimalist period and its emphasis on rectangles and repetition was ending, and people began to turn their expectations to the sculptures from the Mono-ha school that were attempting to overcome this, and painting was having a tough time of it. She gave up on painting as soon as she left university and began creating works that could only be described as a subgenre of post-Mono-ha, and she was largely unable to move on from there (although her installations using glass and rope in the early 1980s did lead to later interest). One thing worth mentioning about this experimental period from our contemporary perspective is that the growing interest in feminism at that time sparked a movement for solidarity between Kurimoto and other women artists around her age, but I would like to speak on that at a different time.

-

Installation view of ʻWOMEN’S ART NOW – 14 to ∞’, Sakae Central Park Event Court, Nagoya City Museum, 1983. Photo by Hiromu Narita (Kurimoto’s work is the work on the floor in the center).

Let’s return to talking about windows. From her second solo exhibition ‘the windows’ (1988) at Stegosaurus Studio in Yamato Seimei Building, Kurimoto began to incorporate the somewhat unusual space into her works. A sort of “honeymoon relationship” between the artist and the building, or perhaps more accurately between the artist and the room, continued for more than ten years, right up until the building was demolished. The starting point of this relationship, and the motif that would remain a constant until the end, was the window. She was on a honeymoon with those windows. If we take a look at her university graduation work, we see, behind a combination of symbolist figures, a depiction of windows, so perhaps her old approach to painting was already foreshadowing her future works. In ʻthe windows’, she used the view visible from the window of the Stegosaurus Studio on the sixth floor of the Yamato Seimei Building to paint the wall and windows of the opposite building, picking up on the joints in the tiles to create a painting of parallels and perpendiculars somewhat reminiscent of a repetitive minimalist grid. At the same time, she would go from the ground floor to the upper floors of the same building, find the same window on each floor, and depict the scene from each floor’s window in black and white. The restrained and sparse honesty touches the heart. Through her simple and frank depictions of the outside world through a window frame, she was able to re-invent her own work and at the same time be reborn as an artist.

-

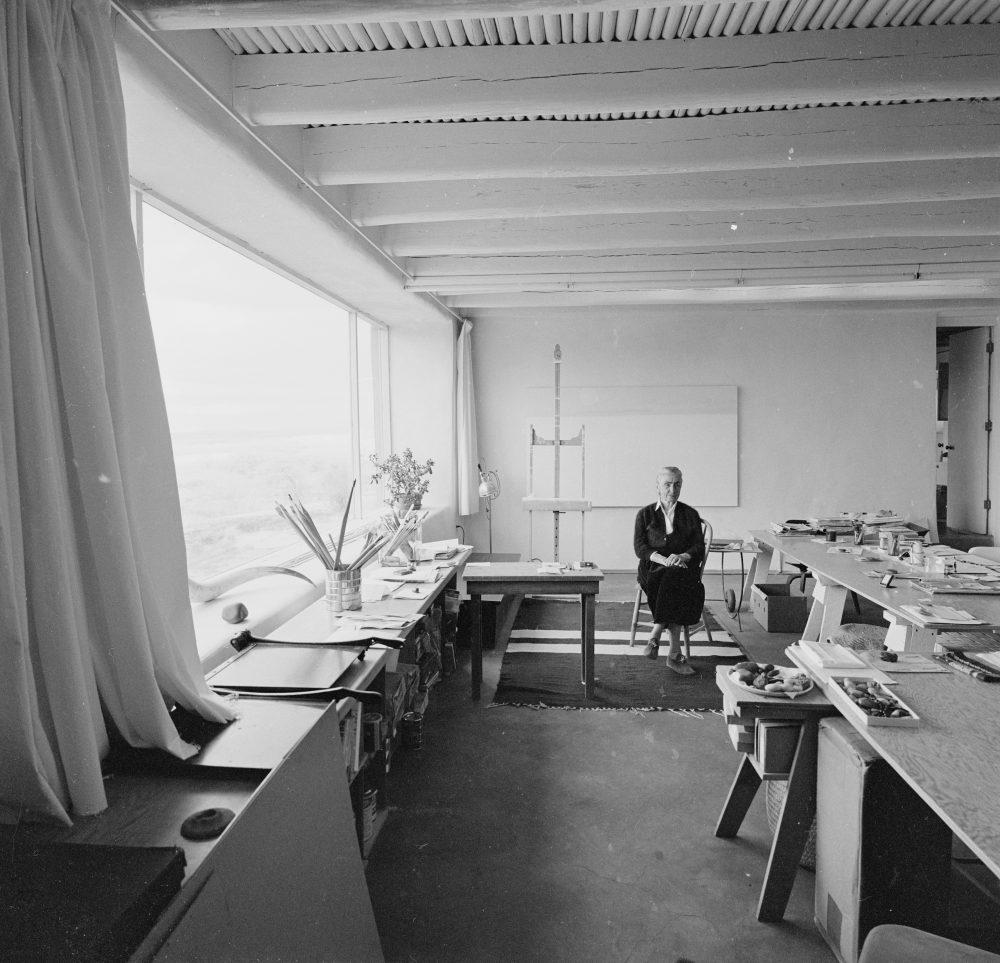

ʻthe windows’, Stegosaurus Studio, 1988. Photo by Hiromu Narita.

-

ʻthe windows’, Stegosaurus Studio, 1988. Photo by Hiromu Narita.

After that, she began to move back and forth between painting and sculpture, incorporating the Stegosaurus Studio space itself into her works. In ʻthe ceiling’ (1989), she reflected the ceiling beams onto the floor, and in ʻthe wall’ the following year, she placed monolithic sculptures in front of each of the windows, each the same size as its window but with added depth. Her approach to intervening in a space was to invert, repeat, or displace the space’s existing components to disrupt our previous perceptions. Here, the window served as a symbolic boundary between the outside and inside worlds, but by sometimes placing gauze or sheets over the windows, the window also functioned as a thing that could control light and create bounded spaces. This may seem like an obvious function for a window. However, if her goal was not to merely create a funhouse that toyed with perception, but rather to redefine the window and the nature of boundaries themselves, and to express in her own way what exists in the space in between, then highlighting the function of the window itself, or transforming a whole room (and not only rooms, but also large-scale installations which sometimes took up entire spaces) into a “window” may have been her aim.

-

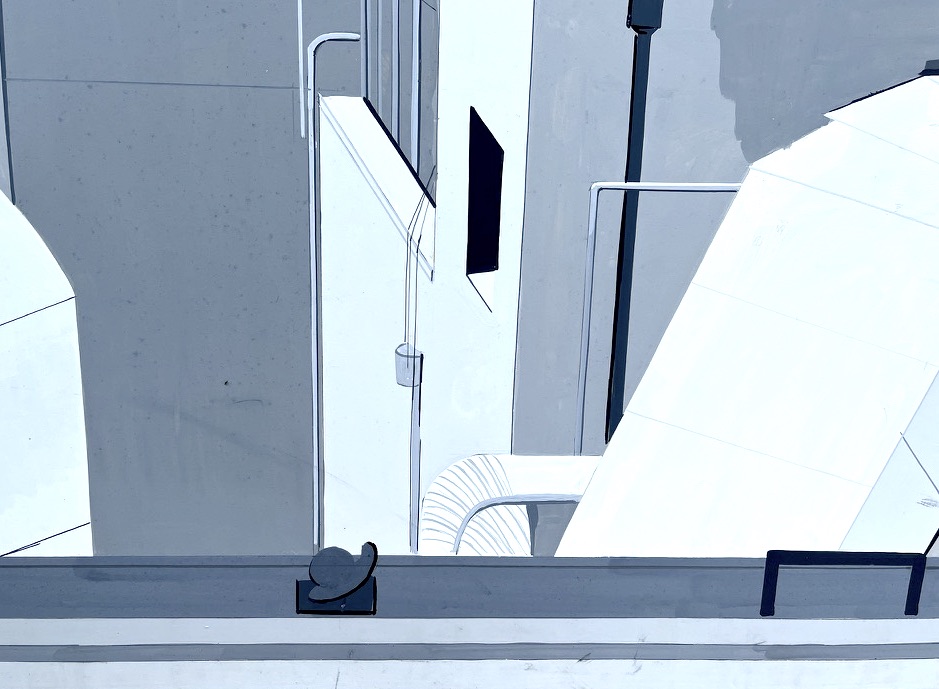

ʻthe wall’, Stegosaurus Studio, 1990. Photo by Hiromu Narita.

Going back to paintings of windows. The important part about these paintings are the unexpected details that indicate that these paintings are, indeed, of windows. If she had drawn just the window frame, it could have been difficult to tell whether the image was of a window or not. It’s because window parts such as the key and the handle for opening and closing it are drawn, that we finally understand that there is glass there. It is almost like the way that the 15th century Italian painter Francesco del Cossa painted a large snail on the edge of his painting of “The Annunciation” in order to depict the painting as a window opening up to a world (although it is just a coincidence that the window key in Kurimoto’s painting also looks like a snail). Or, to continue with our analysis in reference to “The Annunciation”, we are also reminded that glass, being a transparent material through which light could pass, was considered an analogy for the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. I am not sure whether Kurimoto was aware of this context (she probably was not). But in any case, Kurimoto once again departs from detailed painting while leaving in specific elements such as the locks and handles of the actual existing window, and by inserting white, paper-mache structures, she triggers an interaction between the space and the work that creates a window-like, in-between area.

-

Detail of ʻthe windows.’ Photo by the author.

Looking at “Museum Windows”, a painting made at around the same time that features as its motif monochromatic colors that look like rectangular reflections of light in the window glass, and her unpublished studies, which seem as if they’re attempting to depict the light itself that is caught in the window glass, it makes me wonder if she was trying to pause endlessly within that fleeting interval, to find a pure, impossible place where she could stand still in the space that lies in between the beginning and the end. A place where light pauses, but not like an impressionist painting or a photo. A place through which various things, outside and inside, come and go, exchange and connect and grow close; an impossible place where such happenings are possible. What I mean by impossible is the impossibility of a standstill, just as the light that passes through a window cannot come to a standstill within the glass. Kurimoto’s practice must also have been about embracing such impossibilities. None of her installations from the Yamato Seimei Building remain, and she had no intention of preserving them anyway. The building that was the stage for these installations is also gone. And Yuriko Kurimoto is gone, too. They have all passed on. And the people who remember her also pass on, one by one. The brightness of passing. The brightness of her window paintings, which existed, just like windows, in between two worlds. And the window to her life, which is– and was– in passing, just as bright.

On a related note, there is another artist who, like Kurimoto, has made use of the window of a tall building, although this one is in Roppongi. The large window overlooking the city from a skyscraper’s 53rd floor was covered with red film by artist Takuro Tamayama. At a recent group exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, Tamayama chose the museum’s most unique exhibition room and somewhat violently transformed it into a world of bright red, creating within the room a structure in another dimension, a structure that was like architecture, or an interior object; that is, a structure that was like the outside and the inside at the same time– an uncategorizable black object. The window, which was perhaps the work’s origin, was in a sense half-killed, and it is in that space that the work takes its final form, standing between “what has become and what will be gone”. In regards to this superb exhibition at Roppongi Crossing, I hope to one day hear the artist’s thoughts about how he thought of and viewed windows.

Toshiharu Suzuki

Curator at Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. Graduated from the Graduate School of Letters, Nagoya University. Recent major projects include ‘Gerhard Richter’ (2022-23) and ‘Beuys + Palermo’ (2021-22). Part-time lecturer at Nagoya Zokei University.