Series Takashi Homma’s Conversations on Photography

From the “Window” Snapshots of the 1970s to Contemporary German Photography

03 Oct 2018

Candida Höfer is one of Germany’s leading contemporary photographers. She studied under master photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, and is today widely known as a practitioner of the Becher school of photography, along with other figures like Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, and Thomas Ruff. Together with Takashi Homma, with whom she is currently showing her work at the exhibition “A Gaze into Architecture: Phases of Contemporary Photography and Architecture” at Archi-Depot Museum, Höfer looked back on her days as a student in Düsseldorf and her artistic output up until the present.

Takashi Homma: I know that you previously exhibited a series of works entitled “Window.” Were these works snapshots that you had taken yourself, or a collection of photographs taken by other people?

Candida Höfer: Most of the works in “Window” were photos that I had taken while I was attending the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. However, I only got around to putting these photos in order in 2012, so that became the year that the series was made. All of these images are of windows, and each of them was taken in Düsseldorf.

When I opened my solo exhibition in 2013 at the Museum Kunstpalast, one of the largest museums in Düsseldorf, one of the museum curators suggested that it might be a good idea to show both the past and present of Düsseldorf, as well as my past and present works, since I had been taking photos of the city since my student days. So we decided to do an exhibition that consisted only of photos of Düsseldorf. And this “Window” series was made up of photos from my student days that I had never shown before, which I went back to try and put together.

-

Projektion Düsseldorf III 2012

From the "Window" series that was shown at the Düsseldorf exhibition at the Museum Kunstpalast in 2013

These photos were taken while walking around the neighborhood where I used to live as a student. You can see my reflection in various windows, and you can tell that these photos were taken at all times of the year: in one photo I am wearing fur, for instance, while in another I am clad in light, summer clothes. Although I was aware from the very beginning that my own likeness was reflected in these windows, when the photos were projected or printed, this likeness appeared more clearly than I had imagined, and my interest was piqued.

Homma: How was this series exhibited?

Höfer: This series was shown as a projection, without printing the images. Each image was shown one at a time, for about two seconds each.

Homma: Together with other series?

Höfer: No, only the “Window” series was shown in a single loop, without mixing them with other photos.

Homma: Did you take these photos from the outset with the intention of putting together a collection of just windows? Or did you assemble this series because you had accumulated these window photos over the course of taking various snapshots?

Höfer: The idea came to me while I was shooting them. When I saw that my own self was reflected in these photos, it occurred to me that I could make a window series.

Homma: Was it important for you, then, that you were reflected in these images?

Höfer: While I was shooting these photos, I was focused on the act of taking windows. In particular, I wanted to capture shop windows, and this was what drove the series at the start. Gradually, however, I became interested in the fact that my likeness was being reflected in these photos.

Windows capture light, so they are an important element in my other works, as well. For instance, if you look at my work from 2011 in which I depict the interiors of the Benrather Schloss on the outskirts of Düsseldorf, the light that enters the windows is reflected off the floor, creating a series of gradations. This is an extremely large piece, measuring around 1.8 meters high. It was shown as a print for my solo exhibition in Düsseldorf.

-

Benrather Schloss Düsseldorf V 2011, C-print

Interior of the Benrather Schloss The light that enters the windows is reflected off the floor, creating a series of gradations

Homma: Thomas Ruff, who was your classmate at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, is also known for his large format prints. For which series did you first start to make large prints?

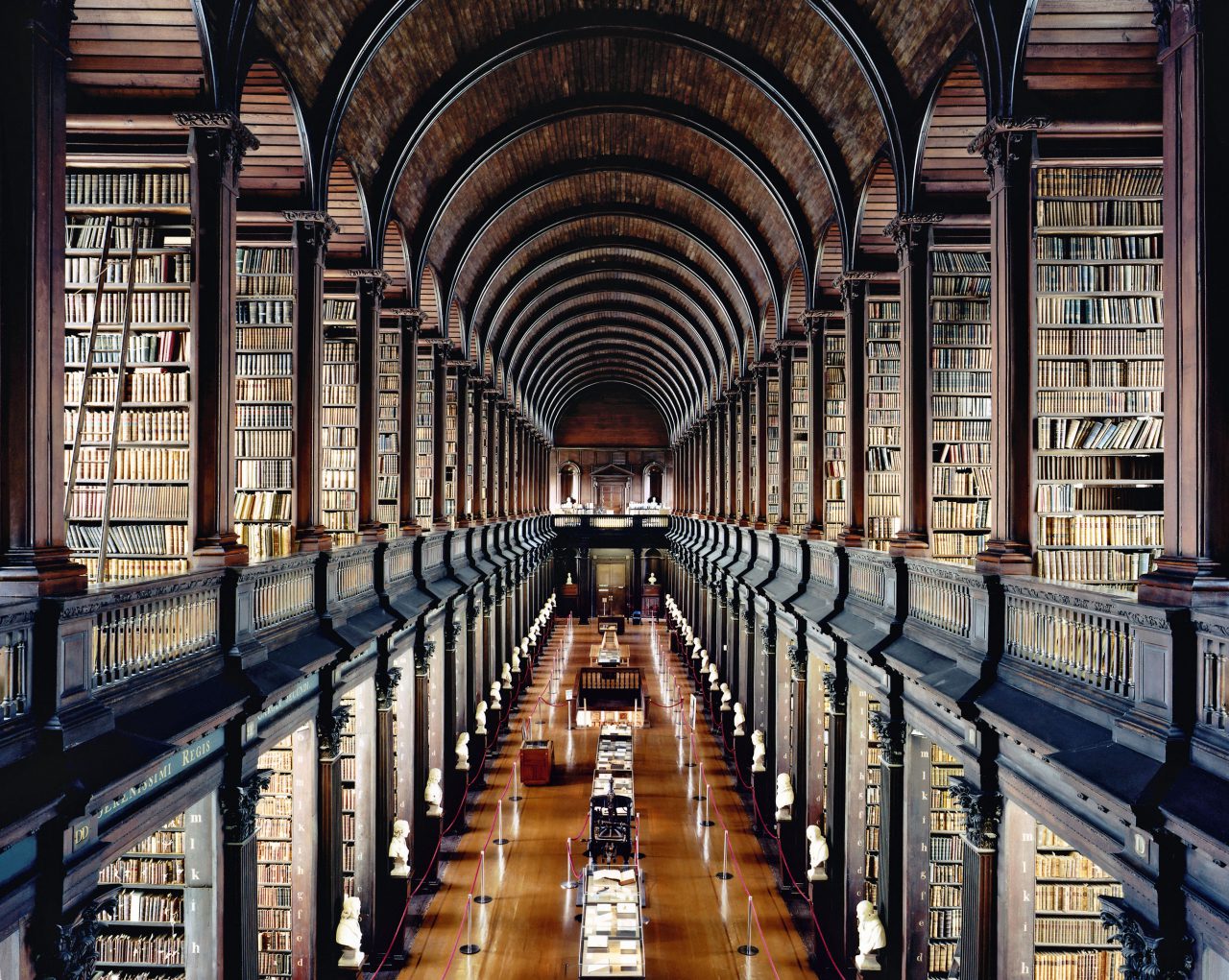

Höfer: While I was shooting the library of Trinity College at the University of Dublin in 2004, I remember standing in front of my camera, which had already been set up, gazing at the room together with my assistant, and saying that I might not be able to capture the scale of that space without a larger camera. Although this print actually measures 1.8 meters high, it was produced entirely through analog means.

-

Trinity College Dublin IV 2004, C-print

The first large format print that Höfer made

My largest work, a photograph made in 2006 that depicts the landing of the Palacio de Monserrate in Portugal, measures 2.49 meters high and 2 meters wide.

To me, the act of making large prints was extremely important not just for Ruff, but for all of us who had studied under Bernd and Hilla Becher. The cost of production goes up when the size increases, however, so as a student it was rather difficult for me to produce a large print, and then even to have it framed.

-

Palacio de Monserrate Sintra 2006, C-print

Photo of the Palacio de Monserrate, the largest print among all of Höfer’s works

Homma: What sorts of things did you learn from the Becher classes?

Höfer: The Becher classes were extremely small and intimate. The students all respected the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher and understood its importance. Even during a shoot that could easily have been influenced by the weather, the Bechers skillfully controlled the light while creating extremely delicate and detailed work. Although I am sure they wanted the time to pursue their own work, they considered us, their students, to be equally important as their own output, and always made time for us when we needed them. There were even times when the class would be taking photos together, and Bernd would say, “the light’s too strong, isn’t it?” He would stop the session right there and we would all go and have a coffee and chat.

Homma: Who else was there when you were taking their classes?

Höfer: I think Ruff must have joined the class after I did. Then other students like Axel Hütte and Petra Wunderlich showed up. And I believe it was Andreas Gursky who came along just as I was leaving. For me, the presence of Axel Hütte and Thomas Struth was particularly important: they also helped me to produce the projections for my Türken in Deutschland 1979 exhibition.

Homma: I’ve been to the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, too, to do some research. Originally, it had a long history associated with painting and sculpture rather than photography, didn’t it? Speaking of which, I believe Joseph Beuys attended the school as well. Were you influenced by forms of art other than photography while at the Kunstakademie?

Höfer: Today, the photography department is also housed in the main building, but when I was a student, the photography classrooms were located far away from the school itself, so I didn’t really have the opportunity to interact with students from the other departments. The stage design department and the oil painting department where Gerhard Richter was, however, were close by, so I did know people there. Although I wasn’t conscious of it at the time, I do believe I may have been influenced by them in some way.

-

Kunstakademie Düpsseldorf III 2011, C-print

A corner of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf that Höfer later photographed

Homma: Any questions from the Window Research Institute?

Window Research Institute: I believe you have been photographing quite a lot of architecture recently. Have you ever shot in Japan?

Höfer: I am interested in architecture, but I don’t really consider myself an architectural photographer. My interest is in the spaces within buildings.

I come to Tokyo about once a year, not to take photos, but just to stroll around the city to absorb something of it. Recently, I often take a small camera and walk around taking photos. I shoot details of things that I find on the street, or some feature of a building, mostly focusing on the finer details.

Homma: So it’s more about the spaces, rather than architecture per se. One of the series I particularly like is the one that depicts On Kawara’s works within interior spaces. How did that series come about?

Höfer: One day, On Kawara and the curator Kasper König came to visit my gallery in Cologne. I was really curious what the matter might be, and when I spoke with them, they asked if I would consider doing a project that would use photography to document Kawara’s works in private collections. A few days later, they sent me a schedule, a list of the collections, and where they were located. It seemed really intriguing, so I decided to accept.

Homma: Roughly how many works were there?

Höfer: Almost all of them (around 140) are included in the monograph Projects Done. Although it might be out of print now, there is also the book from Thames and Hudson that I think may contain some of the other photos.

-

On Kawara: Date Paintings in Private Collections was published by Walther Konig in 2009, bringing together Höfer’s photographs of On Kawara’s painting works in the homes of private collectors.

Homma: You also shot in 6×6 cm format.

Höfer: Yes, using a Hasselblad (the Swedish camera manufacturer).

There are also photos that I took of Kawara works in Japan — his daughter was the one who took me to visit all these collections. I’m fundamentally a very shy person, so at the beginning I hesitated to enter into other people’s private spaces. But everyone was basically really happy to oblige, so I was able to slowly become comfortable, and create an environment where I could concentrate on my work. I never really had the chance to visit Japanese houses, in particular, so it was really stimulating for me to be able to steal a glimpse of the inside of people’s houses through this project. And the experience of having been able to travel all over Japan with Kawara’s daughter and people from his gallery, from Tokyo to Yamaguchi, was a wonderful one.

This series was not exhibited anywhere — it was basically just turned into a book. That was the nature of the project from the very beginning. After it was published, however, I received a proposal through On Kawara, which involved printing several of the photographs and displaying them by laying them out on a glass table.

-

Portrait of Candida Höfer through windows by Roman Lang

Homma: Could we have one final question from the Window Research Institute?

Although I believe they weren’t taken by you, I saw a few portrait photos of you that were taken through a window, and was interested in how there seemed to be some significant overlap with the windows in the “Window” series that you produced as a student. What do windows mean to you?

Höfer: As you know, my photographs depict the spaces within buildings — or interiors, basically. What intrigues me deeply about windows is the fact that through them, elements from the exterior can enter, and things from the interior can leave to go outside. To put it another way: the inside can see what is outside, while that which is outside can enter into the inside.

Inside and outside, while the self becomes one with the window and is projected onto it…

Höfer: I concentrate on my work when I’m taking photos, so I haven’t really thought about it as deeply as that…(laughs)

Candida Höfer

Born in 1944 and based in Cologne, Germany, Höfer is one of the leading exponents of contemporary German photography. She attended the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1973 to 1982, and studied photography under Bernd and Hilla Becher after first studying film. She attracted international acclaim for her large scale works depicting frontal views of luxurious, expansive architectural interiors, such as libraries and palaces. Höfer has shown her work at various museums including the Kunsthalle Basel, Kunsthalle Bern, the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She participated in Documenta 11 in 2002, and represented Germany in the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2003. In 2013, she held a solo exhibition at the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf. Her works are in the collections of numerous museums all over the world, including the Centre Pompidou (France), the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Takashi Homma

Born in 1962 in Tokyo. Homma received the 24th Kimura Ihei Award for photography in 1999 for his work Tokyo Suburbia. From 2011 to 2012, his first museum solo exhibition New Documentary was held at three art museums in Japan. He is the author of Tanoshii Shashin: Yoi Ko no tame no Shashin Kyoshitsu, and numerous photo books.

In 2016, the British publisher Mack published The Narcissistic City, a collection of Homma’s camera obscura series.

“A Gaze into Architecture: Phases of Contemporary Photography and Architecture”

Period: August 4 (Sat) — October 8 (Mon/holiday), 2018

Venue: Archi-Depot Museum (2-6-10, Higashi-Shinagawa, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 140-0002)

Hours: Tuesdays – Sundays 11am–7pm (last entry at 6pm), closed on Mondays (Open on a Monday when it is a National Holiday, in which case closed the following Tuesday)

Admission: Adults ¥3,000, Students ¥2,000, Under 18 ¥1,000

Exhibiting artists: Thomas Demand, Mario Garcia Torres, Naoya Hatakeyama, Candida Höfer, Takashi Homma, Tomoki Imai, Luisa Lambri, Ryuji Miyamoto, Thomas Ruff, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Risaku Suzuki, Tomoko Yoneda, James Welling

Organized by Archi-Depot Museum

https://archi-depot.com/exhibition/a-gaze-into-architecture

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Takashi Homma’s Conversations on Photography

Shizuka Yokomizo + Takashi Homma

The Origin of the Idea26 Sep 2016

Takashi Homma’s Conversations on Photography

MOMAT Collection “Windows and Photography”

06 Sep 2016

Takashi Homma’s Conversations on Photography

Takashi Homma + Alec Soth

Thinking about Windows through Photography06 Jul 2016

Takashi Homma’s Conversations on Photography

Thinking about Windows through Photography

17 Dec 2014