Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Kinnaur District, North India: The Overhanging Village (Part 2)

19 Apr 2018

Many valley-side settlements located 2-3,000 meters above sea level can be found in the district of Kinnaur. Busses run daily even here in the mountains of North India, a part of the world surely once thought of as unexplored. We now live in an age where it’s surprisingly easy to travel to these villages, so long as you can put up with the bus’s swaying (though the shaking is quite bad).

-

The Valley-Side Town of Sangla

I traveled down a road that goes alongside the Buspa river, which diverges from the Sutlej, a river that flows next to Sarahan, and arrived at Sangla in the evening. It seemed to be a relatively large town, with four-to-five-story reinforced concrete buildings lining the main road that our bus drove through.

According to the proprietor of my lodgings, these concrete buildings are almost entirely for commercial use. The people of the town continue to have warm, traditionally constructed homes built from alternating layers of stone and wood.

“You’ll only find dogs on the main road in the winter,” he told me, as someone who returns to the village of his birth during the town’s snowbound winters. The people do not work while the commercial concrete buildings are empty during the winter, spending the days eating, drinking, and dancing instead. He laughed when I told him that Japanese people continue to work throughout the winter, saying, “That’s why Japan is so well off.”

I discovered an abandoned home in a settlement near the river. Just as I saw in Sarahan, its core is made of alternating layers of stone and Himalayan cedar, and it has an overhanging second floor.

It seemed as though it had been uninhabited for quite some time, as parts of it were broken all around, but its sturdy columns that support the overhanging area were something I had not found in Sarahan.

-

An Abandoned Home in Sangla

I decided to let myself in and survey the building. The second-floor terrace area is surrounded by arched and ornamented windows and wooden walls, and the space between it and the building’s core has been made into a long, thin room. While it is a bit tight, measuring only about a meter across, buffer areas such as these must be convenient for both lighting and living purposes. It has contrasting windows that connect the relatively bright space from the outside to a closed, almost windowless space. Seeing the settlement from here made me feel calm and somehow nostalgic. The walls of the second floor are coated in mud, probably due to the significant chill during the winters.

-

Inside an Overhanging Space. We See Two Inset Windows.

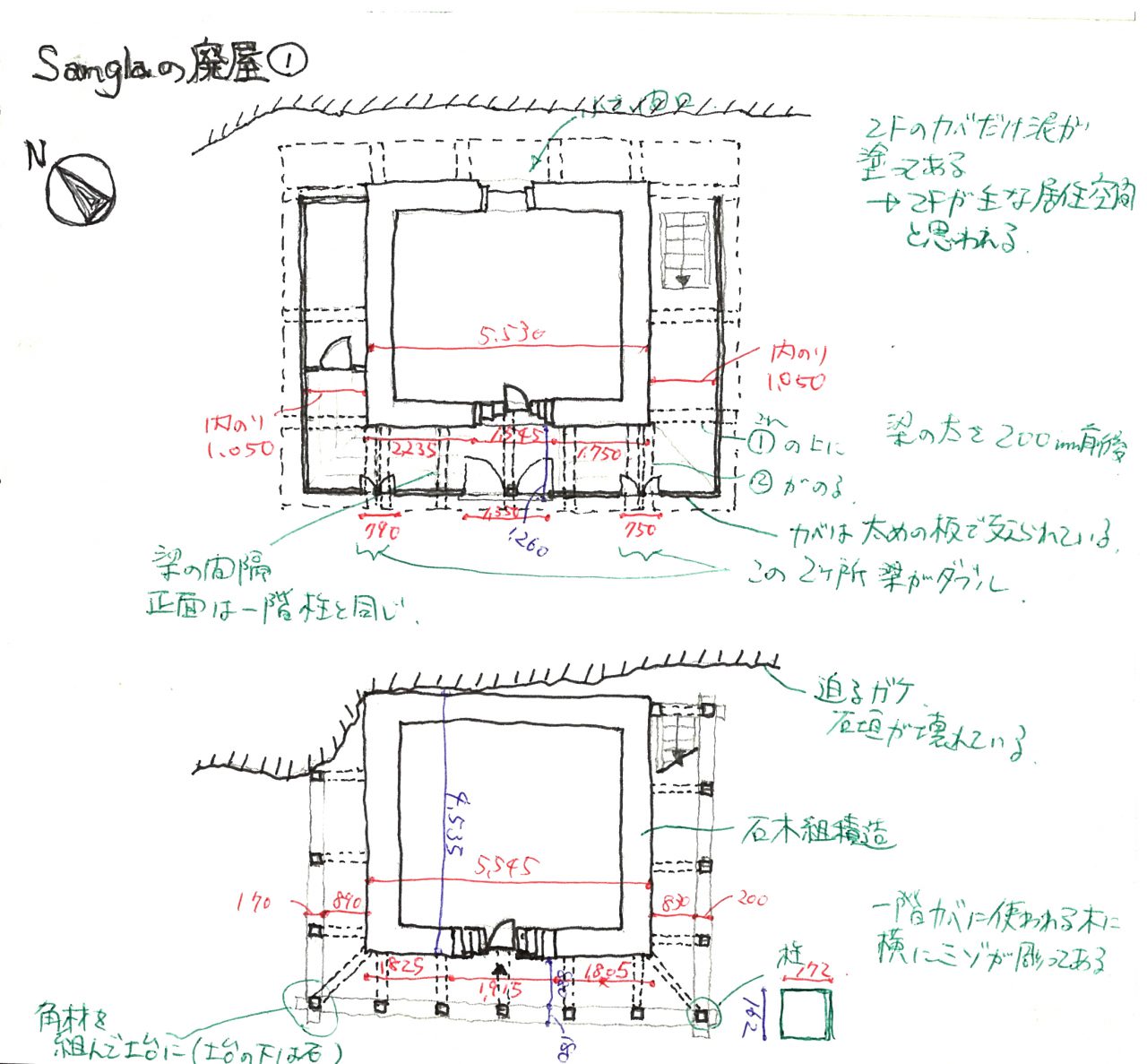

I tried drawing a sketch of the floor plan, which allowed me to see the neat contrast between the building’s core and its surrounding wooden structure. After seeing these two villages, I was able to understand that religious and home architecture in Kinnaur are constructed in nearly identical ways.

-

Floor Plan Sketch of the Abandoned Home in Sangla

I got on yet another bus from Sangla, which I rode until I arrived in Chitkul, the village closest to the India-China border. It is the innermost village in Kinnaur District, and the Tibet Autonomous Region is located just beyond its mountains. The homes here are densely packed, and their newly-built sheet metal roofs reminded me of villages in Japan.

-

The Village of Chitkul

After securing a place to stay at a price of about 500 yen a night, I decided to walk around the village. With few concrete structures, it appeared to still be a primarily agricultural village. Children and livestock wandered the place here and there.

-

A Yak Spotted in the Village

Most of its homes are built in the same way as the previous two villages I visited, and I noticed a large number that looked quite old. Traditional Kinnauri people wear knit wool pants and green felt hats, and I saw many people here in particular wearing such clothing.

-

Extremely Old-Looking Homes

I met a young man who said he makes pants at his family home. He told me many things about life in the village, such as the fact they have running water twice a day in the mornings and evenings, that each family has its own food storage, that livestock live in the first floor of a family’s home, and more.

I thought it would be nice to order some pants 3,500 meters above sea level and decided to ask if I could visit his home to inquire about the topic.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.