Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with François Charbonnet (Made in)

25 Jan 2024

Made in is a highly acclaimed architecture firm that was founded in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2003. François Charbonnet, one of its co-principals, formerly taught as a visiting professor at ETH Zurich and the Academy of Architecture of the Università della Svizzera Italiana in Mendrisio, and published his first book Portraits: Architectural Parables (Park Books) in 2023. Momoyo Kaijima and Simona Ferrari (ETH Zurich Chair of Architectural Behaviorology) asked him about how the firm approaches the design of windows.

Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (CAB): Windows go beyond architecture to serve as highly technical components of transport infrastructure, as you see in trains or cable cars in Switzerland. A project like Villa Chardonne seems to relate to windows of this kind. What role do windows play in your design process?

François Charbonnet (FC): To be perfectly honest, we hardly see the window—or any elemental feature for that matter—as a primary issue within the design process. I am well aware that one can build a house around a singular variable, but we tend to consider structural and programmatic challenges to be more central to the development of a project. In the case of Villa Chardonne, our clients’ expectations were (as is often the case) quite unspecific on all accounts, except for the fact that they wished to be able to experience the setting in the open. With quite a narrow and limited plot, the outdoors was for them the only real cardinal attribute of the design. But a quick look at the legal requirements showed an obvious conflict between a comprehensive use of the landscape and the footprint of the actual house: two thirds of the available site could in fact be occupied by the structure, leaving only a marginal space for outdoor living. The idea of lifting the house off the ground is therefore an immediate consequence of the clients’ demands, not the manifestation of a demonstrative gesture.

Structurally, the Vierendeel beams are adjusted to absorb their respective deflections under stress—a measure taken to guarantee the leveling of the single floor when loadbearing. Yet the structural framework remains a supple one and its elasticity has implications for the glass infills: to prevent them from shattering, some—the ones in the immediate vicinity of the structural anchor points—show a trapezoid contour, precisely sized according to the estimated deformation of the primary structure. All windows are fixed in place and as a result do not contribute to the natural ventilation of the house. In this regard, several options were considered, but the recessed active louvers set behind the vertical membranes turned out to be the only economically reasonable solution. Relying on the basic principle of convection and located alongside the axis of the partition walls of the house, they offer a relatively high degree of control, allowing each of the separate rooms to be independently ventilated. What I mean to say is that, if the windows of the Villa Chardonne induce a close visual relationship with the surroundings, they primarily and essentially relate to the loadbearing structure; the fact that they are fixed elements severs their physical interaction with the occupant. Intended to vanish, they leave the large opening located at the very front end of the structure as the only mechanically operable glass component of the house.

-

Villa Chardonne (2009) on Lake Geneva, exterior view from the east

©︎ Walter Mair

CAB: Rather than any singular elements, then, your project’s narrative revolves around how one inhabits space and how the envelope mediates the relationship between body and site.

FC: Very much so, for the above-mentioned programmatic reasons as well as for the typical topography of the Lavaux. But of course the most obvious asset of the plot is the scenery of Lake Geneva and its surrounding mountain range. In this regard, the slender structure and its glass infill are an obvious answer to the context, but they also generate a series of behavioral adjustments. The clients had spent most of their lives in a barn conversion with thick walls and narrow windows—the update to their living environment was in fact quite a fundamental one. And beyond a substantial reduction of their program, they also had to concede that a sense of privacy could be ensured by means of layered expertise rather than by sheer mass and limited openings. As a result, a series of prosthetic add-ons—curtains, veils, active shades—expediently complete the windows and turn them into versatile performative partitions: they are essentially as much walls as they are openings. Another notable consequence of the downsized juxtaposed glasshouses of the Villa Chardonne is the comprehensive alteration of the furnishing layout: many belongings, accessories, and fixtures could not find their place within the structure and as a result were disposed of, considerably editing the clients’ living environment.

-

Interior view looking south along the east facade

©︎ Walter Mair

CAB: Le Corbusier’s Villa Le Lac on Lake Geneva certainly provoked a radical change of lifestyle as well. Born into a watchmaking family in La Chaux-de-Fonds, he also incorporated technological innovations, both in the villa and the Immeuble Clarté here in Geneva, which were inspired by the highly mechanized windows of watchmaking workshops.

FC: A window is always more than a technical feature. Like any constituent part of architecture, it is subject to being revisited or amended. I think that ultimately it has to do with a certain commitment to the notion of limit; to not just work with the commonly accepted attributes of a device, but to question and augment its actual properties, or at least stretch it to its own limit. A good example is the display window apparatus developed for a department store in Geneva. The element was inflated in its dimension to provide it with a visual permeability between public and private space. Windows span over 7m segments and display a curvature so as to minimize disturbing reflections (a feature also found in early twentieth-century shopwindows).

-

Display window of Globus Rue du Marché (2017-) in Geneva, view from street

©︎ Made in

But as they must also provide the basement with natural light in addition to visual permeability at street level, they evolve into a hybridization of two distinct requirements: together they form a system of complementary properties and are designed accordingly, that is, not separately but coincidentally. The vicinity of these two distinctive features generates a bespoke sectional arrangement. Yet it is still, as in Chardonne, a passive element of the whole. When operable, a window can additionally become theatrical: sliding, tilting, pulling, lifting, revolving—all these actions upon an element essentially contribute to the prosthetic and functional augmentation of an architectural body but can also offer a whole range of alternate configurations of spaces and uses. In this regard, the window is part of a large repertoire of mechanical fixtures that heighten the experience of inhabiting and endow it with a sense of the “operatic” in addition to the strictly “operational.”

-

View of display window from the lower floor

©︎ Made in

CAB: Movement again links windows and infrastructure: the speed of machines introduced a new sense of motion into modern society. With the glass brick curved facade of the Gleisarena office building you celebrate the dynamic flux of the trains moving in and out Zurich’s main station…

FC: Central to the project of the Gleisarena is its heterogeneous setting and the fact that the building stands on the very edge of two distinct environments: Kreis 5 and its midsized urban masses on the one side, and an exclusively infrastructural field on the other. The project attempts to underline this polarity and shows a specific order on each side of the elongated structure—in this regard, it is very responsive to its context. The double curvature of the platform facade and its slick monumentality account for the dynamic fluxes of the public transit network and relate to the opulence of the nineteenth-century station. In contrast, the Zollstrasse elevation displays horizontal window frames of an industrial scale whose specificity lies in the unusual depth of their profiles and the deep-recessed positioning of their climatic barrier.

Interestingly, glass-brick walls have been around for more than a century and were commonly used in Switzerland in the 1960s and 1970s. Yet over the years they have become scarcer as they hardly meet contemporary standards on thermal insulation. And on a building whose main elevation is towards a harsh western light, the issue can become a serious one. To meet those standards, we tinkered with an off-the-shelf product—rather than redesigning it, we updated it into a double-skin facade with interstitial thermal barrier. The real complication, however, lies in the double curvature of the skin and its geometrical reduction to a singular standing line toward the end of the building. Because of its sheer geometric complexity, each segment has an ever so slightly different setting and needs to be manually adjusted to meet its adjacent module. And as these constitutive elements are squarish, the built volume can in fact only approximate the ideal Euclidean geometry. In this regard, the facade relies almost exclusively on the precise and manual assembling of the different parts in the production facility and on site. Though it was developed by means of computer-aided drafting software, a hand proved necessary to overcome the discrepancy between the ideal and the real. It is rather comforting to know that the human variable still stands at the center of an architectural realization.

-

Gleisarena (2014) in Zurich, general view from main station

©︎ Walter Mair

CAB: Your windows are indeed a materialization of a process of negotiating limits—not just the limits of materials and technology but the boundaries of what society accepts today.

FC: As I mentioned earlier, we have always been interested in the notion of limit—as frankly any architect should be, since their most essential operation is, I think, that of division: outlining margins and defining borders are probably some of the most basic operations in any architectural design. But your question implies another edge, one that is less physical and more conjectural. I personally believe that if you want to state or do something significant, then you need to do it at the boundary of your own knowledge and ignorance or, in other words, on the thin line where accumulated expertise is challenged by unprecedented circumstances. It is precisely here that architecture as a process can become exhilarating and relevant. Of course, the basic requirements hardly evolve over time—the Roman domus would probably still fulfill most of our daily needs—but each case remains a specific one, and because there is no indisputable grammar of architecture there can simply be no generic answer to a specific issue. That is to say, a convention, or any arbitrary certification for that matter, can and should be questioned in order to provide a performative and stimulating environment; and this implies an intense negotiation with the notion of limit itself, be it the physical resilience of a material or the conformist expectations of a client.

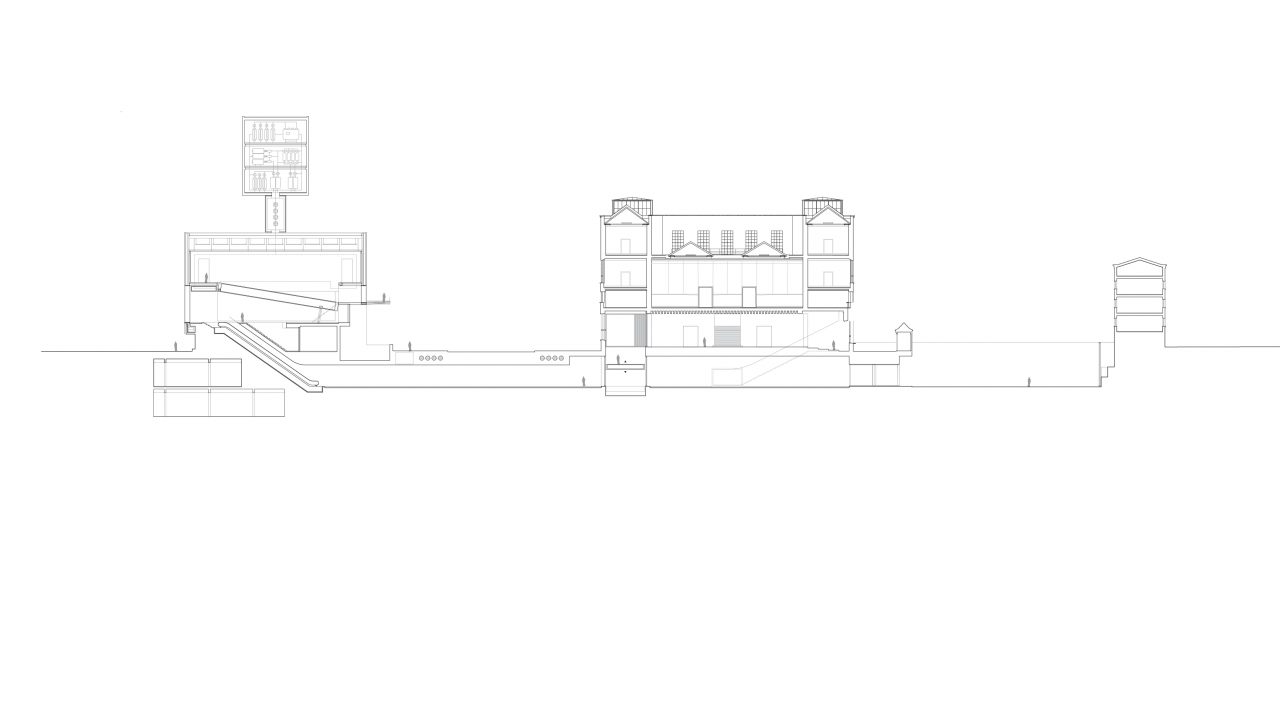

CAB: How did you envision the experience of the large glass envelope in your competition proposal for the Kunstmuseum Basel extension? There you even have moving walls and floors…

FC: The brief for the Kunstmuseum Basel called not only for a new temporary exhibition space but for a massive programmatic extension—60,000m2—of the permanent collection. And as the suggested agenda would have overloaded the site, which is near a very sensitive part of the city, we looked for a way to reduce its footprint. We planned an extensive reallocation of the lower floors of the existing building—which are currently used as a storage facility— to draw everything pertaining to the permanent exhibition together and avoid splitting the program into autonomous parts.

The new site exclusively hosts the gallery for temporary exhibitions and can either be staged as a looping path by means of a series of prosthetic devices—a retractable ramp, a freight elevator, mechanical stairways—or divided into separate installations thanks to hanging walls that drop down from the ceiling. The underground passage serves as a transitional gallery for media art and operates as a threshold between the permanent and temporary exhibitions. The extension is really a mechanical apparatus that provides the curatorial team with a versatile scenographic tool. The glass facade was not addressed in detail, but it offered a contrasting effect between the solid block of stone of the historical building and the crystalline abstraction of the museal extension.

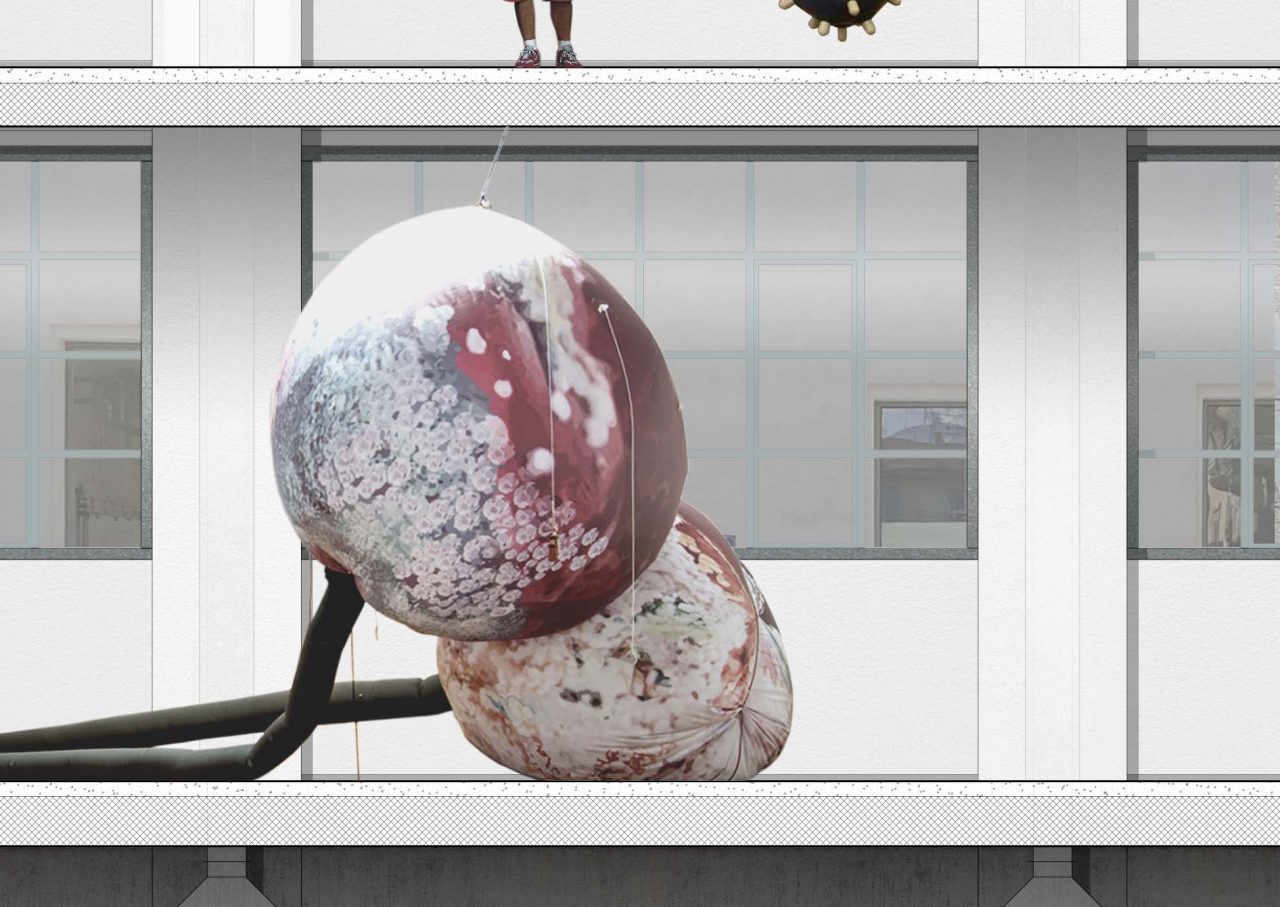

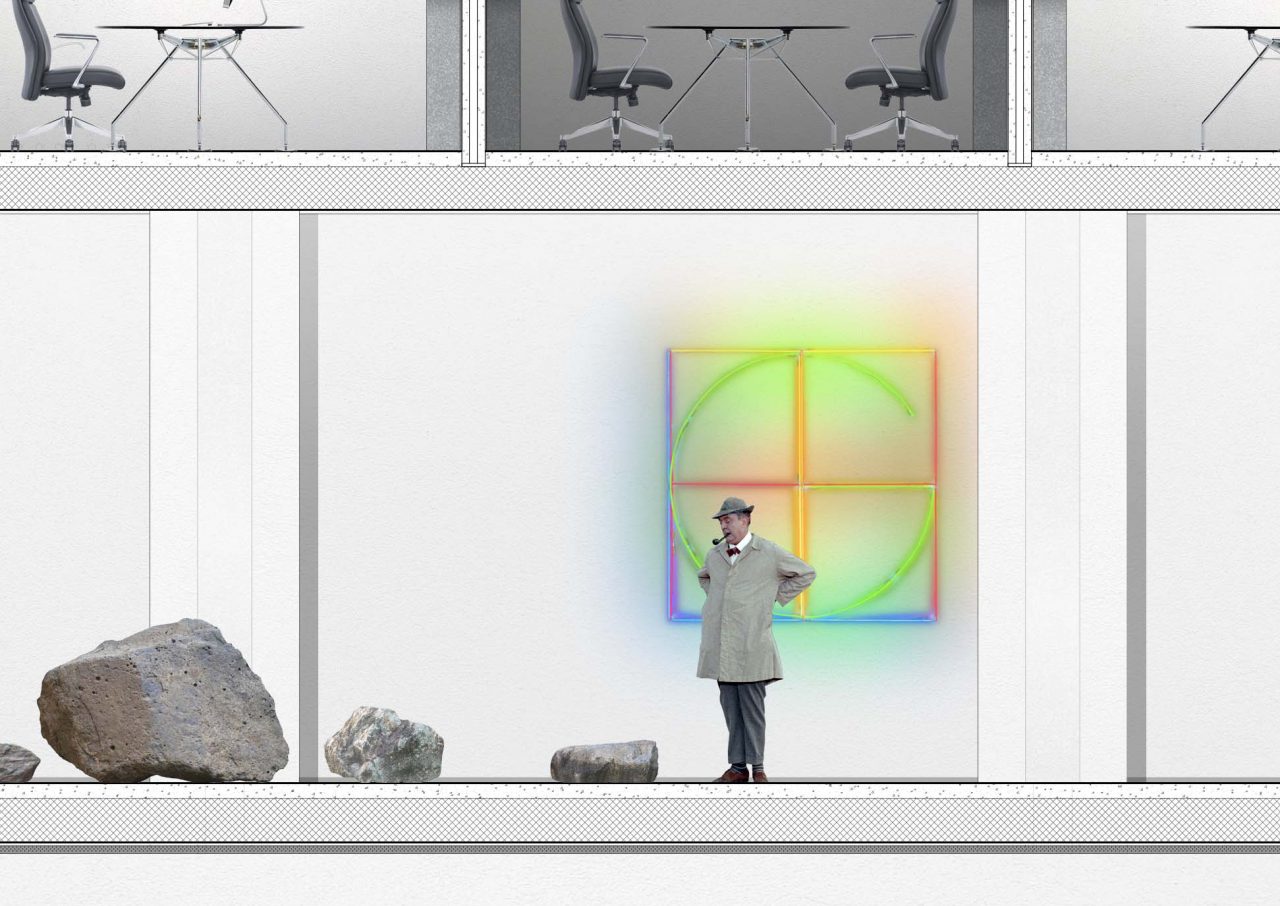

We did develop an intricate 1:1 window in a more recent competition for the Bâtiment d’Art Contemporain in Geneva. Located on one of the very few residual urban blocks dedicated to industrial activity, the main building is a rather shabby one and its performance—climatic as well as scenographic—is far from ideal for the display of artworks. The building shows a series of typical industrial windows with thin profiles; most of its century-old glass is original and unfortunately hardly meets the standards of a contemporary museal institution. The steel frames and their refined mechanism are also in place; strikingly delicate, they seemed very much worthy of preservation. To make the industrial window suitably performative, we proposed to augment it with a triple-glazed closed cavity system set directly behind it: the existing facade remains unadulterated but works in conjunction with the new envelope.

-

Bâtiment d’Art Contemporain (2021) in Geneva, competition proposal. Exterior view with the original window profiles

©︎ ArtefactoryLab

As a result, the historical substance is not a passive and residual component of the whole, but becomes an essentially active one. Another issue to be dealt with was the control of light: converted industrial buildings often provide a highly flexible space and quite ideal structural spans but tend to expose works to an excess of daylight. The window had as a result to become much more than a quantifiable thermal barrier: it had to fulfill multiple requirements, ranging from the insulating performance, through the adaptive management of light, to the scenographic support of artworks, and all without impacting the actual image of the landmark structure.

CAB: To design all these ad-hoc windows have you established regular collaborations with engineers or with industry?

FC: Yes, we collaborate with experts on a regular basis. They tend to consider the collaborative work as stimulating. I like to think the reason they feel that way is that we are inclined to challenge their expertise. But more broadly, and at a time where the atomization of knowledge through specialization has become all-pervasive, the architect remains one of the last generalists able to orchestrate a fragmented field of competences into a meaningful whole, something worthy of being called architecture.

François Charbonnet

François Charbonnet is co-founder, along with Patrick Heiz, of the architecture studio Made in, based in Geneva and Zurich, Switzerland. After graduating from the ETH Zurich with a thesis supervised by Prof. Hans Kollho, he collaborated with Herzog & de Meuron and OMA, Rem Koolhaas before setting up their own office in 2003. François Charbonnet has been a visiting professor at the EPF Lausanne (2010-2011), at the ETH Zurich (2011-2013) and at the Accademia di Archittetura, Mendrisio (2014-2015). In addition to its academic activity, Made in works as an operative practice at redening the outline of the architectural project through an extensive range of private commissions, as well as competition entries, challenging the common acceptation of elaborate design. As frequent lecturers in Switzerland and abroad, Made in is a prominent agent of the debate on contemporary architecture and advocates for a critical and transversal insight of present contigencies and demands.

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at ETH Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan’s Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba since 2009, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), and Columbia University (2017). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city through publications such as Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia. Awarded the Wolf Prize for Architecture in 2022.

Simona Ferrari

Simona Ferrari has been a teaching and research assistant at the Chair of Architecture Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) since 2017. She studied at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Technical University of Vienna, Politecnico di Milano, and Zurich University of the Arts. Her work engages with different scales and formats, from architectural projects to photography and text. She is the co-author of Landscape In-Between, a project for the former industrial site of Acetati in Verbania, Italy, awarded by the Europan competition in 2019. From 2014 to 2017, she worked with Atelier Bow-Wow in Tokyo, completing several international projects, exhibition designs, and installations. She is a recipient of the Monbukagakusho Scholarship and MAK Schindler Scholarship in Los Angeles.

Top image: ©︎ Walter Mair