Series The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Architectural Ethnography, Part A

01 Jun 2018

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Ecology

- Interviews

To commemorate the occasion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia (May 26th-November 25th, 2018), the Window Research Institute caught up with Momoyo Kaijima, curator of the Japan Pavilion, for an interview. Kaijima is a co-founder of Atelier Bow-Wow and has taught Architectural Behaviorology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Aside from working as an architect at the van guard of her field, she brings a uniquely architecture-focused bent to an extensive body of urban research, and we sat down to ask her about this ecological, architectural way of understanding our lives.

In this, the first half of our conversation, we discuss the Architectural Ethnography and its history—a topic vital to this year’s exhibition at the Japan Pavilion—and explore the potential of windows as a new lens through which to view the field of architecture.

So tell us about how you arrived at Architectural Ethnography as the theme the Japan Pavilion’s exhibit.

I’ve always been keenly interested in the relationship between life and architecture—how architecture effects the lives lived around it—and so in 1995 I formed a research group called “Made in Tokyo” with Junzō Kuroda and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, with the mission of investigating the urban space of Tokyo. We began presenting the results of our observations in 1996, in publications and exhibitions, and soon began receiving requests for speaking engagements, letters from people who wanted to show us their own “Made in” projects, and invitations to participate in the “Made in” research in different cities. It turned out that people all over the place—not just in Japan, but around the world—were drawn to the same things we were. We were all interested in trying to understand, through architecture, the changes that our cities and our behaviors were undergoing.

For this show, I wanted to take a step back and revisit at the reports I’d received, the guest lectures I’d given, and all the ways people had tried to conceive of the relationship between architecture and behavior over the last 20 years. In choosing this theme, my hope is that the perspective of broad overview might help illuminate the ways architecture relates to our behavior, and the effects it has on its environs.

How do you understand the influence that your Architectural Ethnography projects have had around the world, since their appearance in 1996?

In the last 20 years we’ve been through a series of international wars, economic catastrophes, natural disasters, and refugee crises, massive shifts in power dynamics in the Balkans and Europe, and a general movement toward restructuring our social and ethnic polities. In the same 20 years the internet happened, and we’ve all suddenly become networked. This has served to globalize everything: we can access information from around the world at the touch of a button, and keep tabs on friends that we would have otherwise lost touch with through social media.

And when we experience these huge changes in our lifestyles and our architecture, we naturally want to pinpoint them, to observe and consider them. The original Japanese ethnographers like Kunio Yanagita, Tsuneichi Miyamoto, and Wajirō Kon all emerged right when Japanese folklore and traditional architecture were being erased by Japan’s rapid Westernization. They wanted to catch the things that were disappearing, and understand the changes that were happening. In particular, the discipline of Modernology that Kon conceived of is literally “Observing and understanding the modern world.”

For this exhibit, I teamed up with the curator for the Japan Pavilion and Professor Laurant Stalder, who teaches the History and Theory of Architectural at the ETHZ (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich), and began gathering reports and projects from around the world. Eventually we ended up with some 200 examples, from which we culled 42 pieces for the exhibition. We can see that those works really wanted to capture the tremendous changes the world has undergone in the last twenty years.

I can only imagine the incredible volume of material you must have assembled. What was your methodology for curating content?

Architectural drawings are a major motif in this exhibition. This is simply because my experience with Made in Tokyo has taught me that drawings are an effective way of recording what one sees, and conveying architectural research to a larger audience.

In the classroom, students of architecture spend a great deal of time doing group research, and architectural drawings are means by which their findings are synthesized and advanced. When students draft a design, their floor plans and cross sections are the language through which we discuss the architectural merits of their ideas, and whether the designs are technically feasible. For any architect, being a capable draftsman is imperative.

Sketches aren’t such a large part of other areas of Ethnography, and I felt like they would be a great for illustrating the role of architecture in the field for the Biennale. And I think the medium makes the exhibit accessible to a larger audience. Among the work we’ve chosen are sketches by visual artists on the theme of architecture and behavior, which accounts for a quarter of the contents of the exhibit.

-

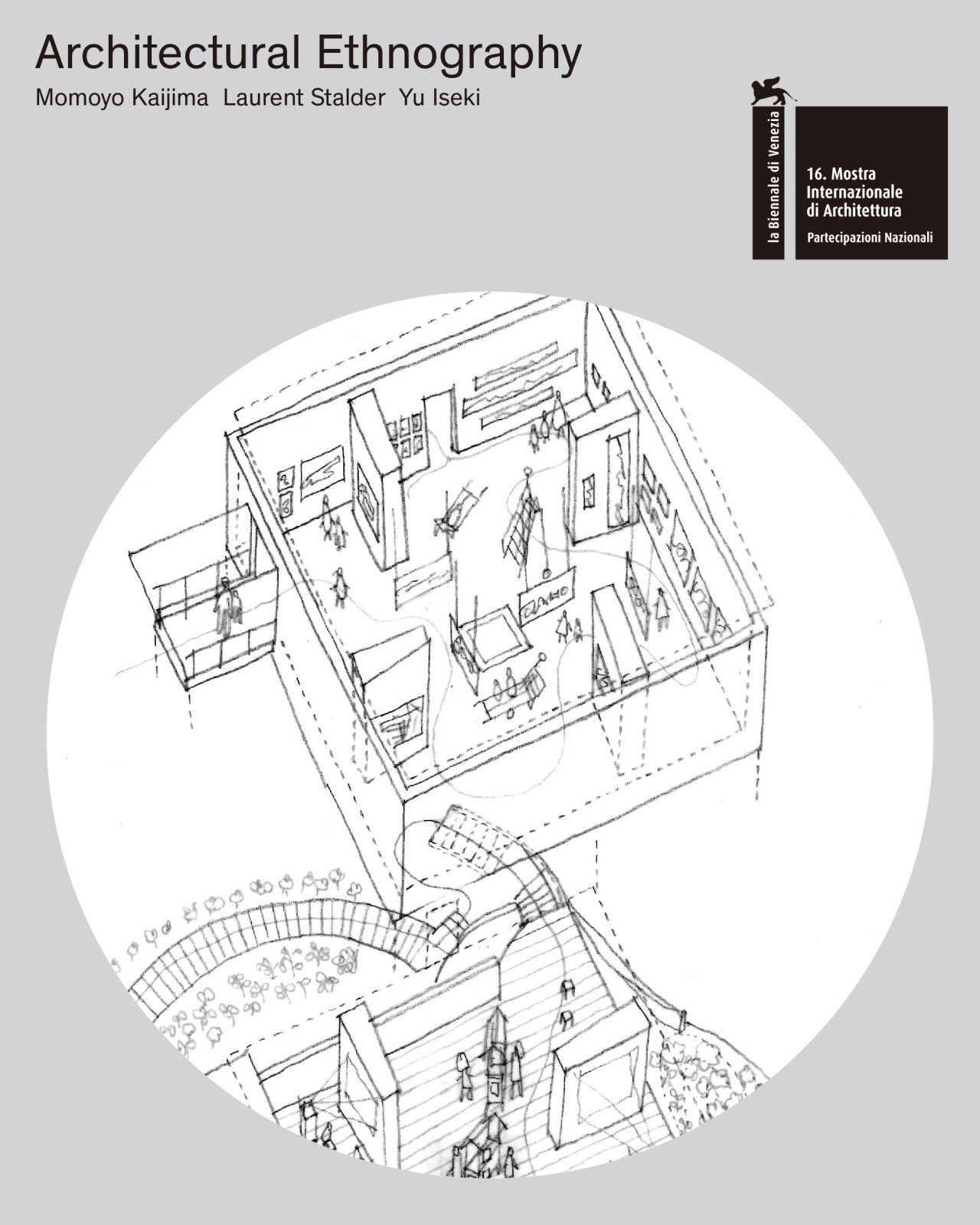

One of Kaijima’s drawings emblazons the exhibition catalogue

Can you talk a little more about these drawings.

They can generally be broken down into four categories. The first would be drawings of architecture. These are simply drawings of existing buildings. The second is drawings for architecture. These are sketches made in order to build a piece of architecture, to architect something. The third is drawing among architecture, which involves sketching architecture among its sundry environs. And the last is drawing around architecture, which is its surroundings. Organizing “architecture” and “drawings” by these four prepositions gives us four rubrics from understand how the former relates to the latter.

And this can be applied to our regular work as architects, as well. Sometimes we understand a piece architecture as a physical object, and sometimes we have to consider the structures and systems necessary to build that object, the concrete steps involved, the intricacies of production and our roles therein. As the effects of large-scale climate change manifest before our eyes, the balance between humans and the earth has shifted so drastically that the environment can’t be ignored as a factor in any project.

I’ve been interested in a lot of the research being done around ecosystems and global warming, but the extremely broad scale and complexity of this sort of work makes it difficult to capture in a sketch. The overview that an architect and her sketches are capable of capturing is ultimately limited to the scope of a single human being. This has been one of the most fascinating and challenging parts of our survey of these drawings: the things that can’t be illustrated, the bits of information that are necessarily abstract, and the ways that we try and visualize and embody our natural and cultural inheritance.

Do you have any examples of how windows have played an important role in the how architecture interacts with its environs?

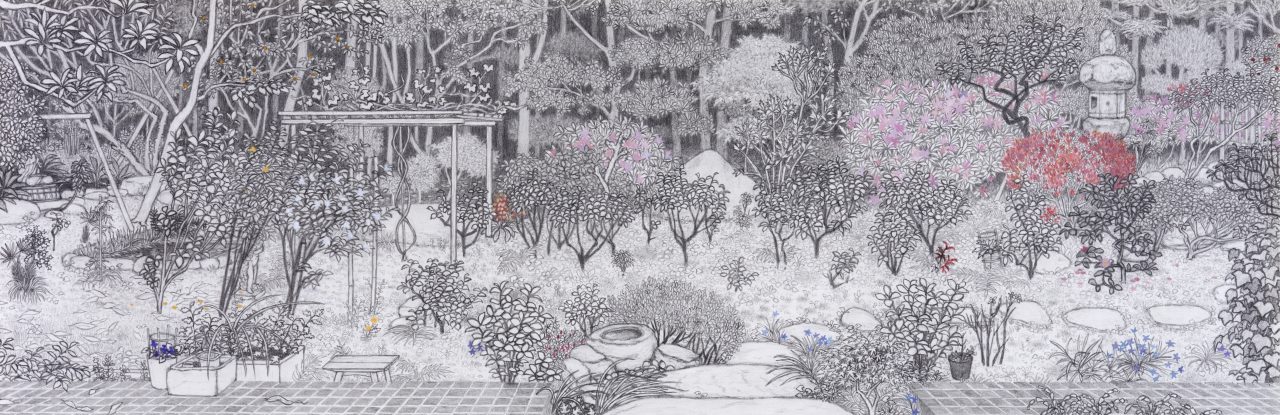

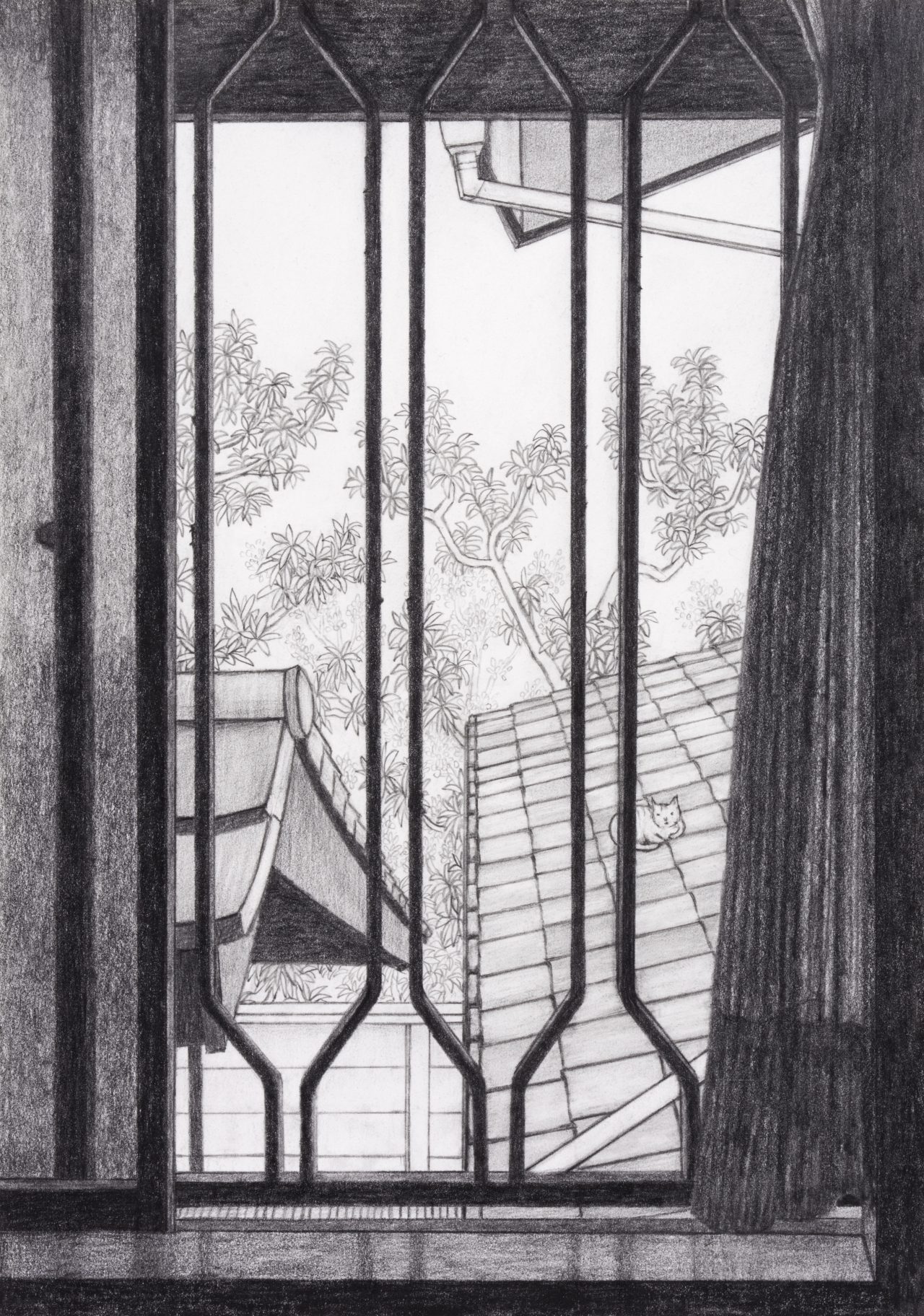

The owner of a private residence sponsored a piece by an artist named Yukiko Sutō. The residence was slated to be torn down, and the owner wanted to capture their longtime home in an illustration, rather than a photograph, so Sutō spent a whole year visiting the house, and talking with the family members and the help while she worked.

Looking at her illustrations, you can actually see how what was originally a traditional Japanese home was gradually augmented over the years. For example, there was a classic stone basin in what had once been a Japanese-style garden, which had subsequently been surrounded with ceramic tiling, turning the garden into this collision of foreign and Japanese motifs. The pictures captured all the changes the home had undergone, as it was lived in and passed down through several generations. And its relationship to its environment and the neighboring buildings had also undergone changes, which you can see in her drawing of windows. Basically, the window a frame for capturing all the conditional and environmental changes happening around the home.

-

© Yukiko Suto, Courtesy of Take Ninagawa, Tokyo

-

© Yukiko Suto, Courtesy of Take Ninagawa, Tokyo

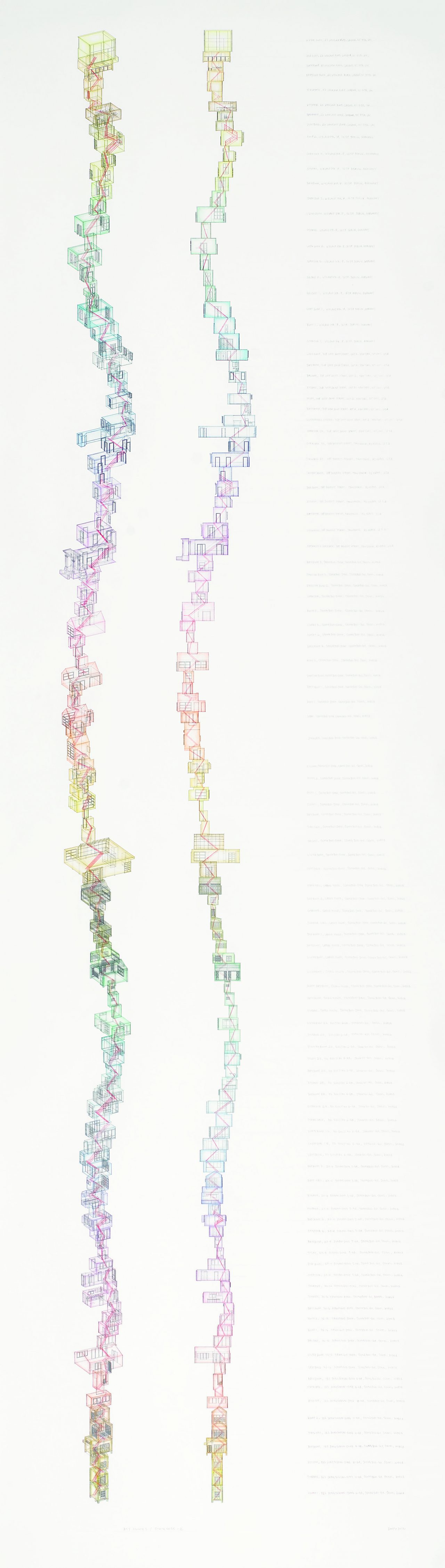

Our exhibit catalogue employs a number of contrivances allowing the reader to actually “look inside” pictures. There’s a piece by Do Ho Suh, for example, consisting of all the houses he’s ever lived in drawn on top of each other, and it’s really a gigantic work—1×4 meters. In the catalogue, of course, we wanted to show the piece in its entirety, without losing the ecology of all of its tiny details, and so we created these little windows, like magnifying glasses, that zoom in on parts of the piece and give you detailed descriptions. We employ this device throughout the volume, with circular windows around elements that we wanted to highlight, letting you peek into parts of various works. We used this same device in the exhibit space, as well, installing magnifying glasses allowing visitors to really look inside the drawings. While it’s important to give visitors a broad overview of the work, many of the pieces are meticulously detailed line drawings, into which the artists have poured untold hours just blocking out their outlines, and the sheer weight of all this time and effort give you a sense of the physicality and devotion of the author.

-

© Do HoSuh, Courtesy of the Artist and Lehman Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, and Victoria Miro, London and Venice

So windows are frames which present architecture from a fresh angle, and serve to elicit specific behaviors from visitors to the exhibition.

Couldn’t have put it better. For some of pieces placed higher up, we’ve even installed ladders so you can climb up and get a closer look. I’m excited to just stand back and observe visitors, and see how they behave around the drawings. Pictures don’t move, but people view them interactively, and I’m eager to take notes on how they do, and perhaps even glean some new fodder for our research.

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition

La Biennale di Venezia, 2018

Theme: FREESPACE

Directors: Yvonne Farrell, Shelley McNamara

Location: Giardini di Castello, Arsenale

Dates: May 26th – November 25th, 2018

Website: http://www.labiennale.org

The Japan Pavilion

Theme: Architectural Ethnography

Curator: Momoyo Kaijima with Laurent Stalder (Associate Professor of Architectural History, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Chief of the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture) and Iseki Yū (Curator, Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery)

Assistant Curator: Simona Ferarri, Tamotsu Ito, Andreas Kalpakci

Curation Team: ETHZ Studio Bow-Wow, Laurent Stalder (Associate Professor of Architectural History, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Chief of the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture), Iseki Yū (Curator, Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery)

Presented by: The Japan Foundation

Momoyo Kaijima

Born 1969, in Tokyo. In 1991, she graduated from Japan Women’s University, where she majored in Housing and Architecture. The following year, she founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto. In 1994, she received her masters degree from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and spent 1996-97 studying abroad at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ). In 2000 she left Tokyo Institute of Technology without finishing her PhD, and spent the next nine years as a lecturer at the University of Tsukuba. In 2009, she became an associate professor at Tsukuba, and received a RIBA International Fellowship in 2012. She has been a professor of Behavioral Architecture at ETHZ since 2017, and has taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (2003, 2016), ETHZ (2005-7), the Royal Danish Academy (2011-12), Rice University (2014-15), Delft University of Technology (2015-16), and Columbia University (2017). While designing residences, public architecture, and train station environs, Kaijima has continued conducting architecture-centered urban research like “Made in Tokyo” and “Pet Architecture.” She is the curator for the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia (2018).

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Thresholds between Coexistence and Architecture

25 Jun 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Interview with Tom Emerson, 6a architects

22 Apr 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Windows: Openings and devices

12 Dec 2018

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Liquid Light

12 Oct 2018