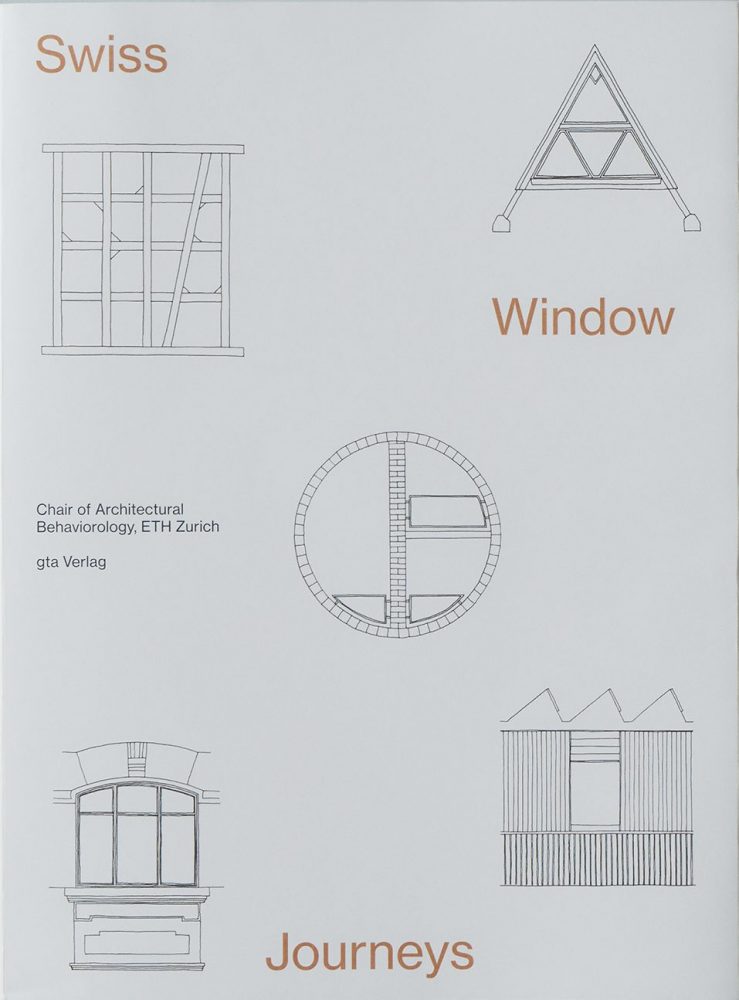

Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Christine Binswanger, Raúl Mera (Herzog & de Meuron)

24 May 2023

Herzog & de Meuron, the Basel-based architectural duo, founded their firm in 1978 after studying architecture at ETH Zurich. They have since designed numerous prominent projects worldwide, such as the Tate Modern, Prada Aoyama Epicenter, and M+. Their accolades include the Pritzker Prize (2001) and RIBA Royal Gold Medal (2007). Christine Binswanger, a Senior Partner since 2009, and Raúl Mera, who is experienced with healthcare projects, spoke with the Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (ETH Zurich), which has been conducting research on the theme of windows and healthcare.

Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (CAB): While investigating different forms of windows in Switzerland we looked at historical examples of sanatoriums in the Alpine region. Places like the Schatzalp Hotel in Davos, which also featured in Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain), characteristically had balconies that gave patients access to the sun and fresh air as part of their treatment. Extending our focus to contemporary buildings, we would like to discuss your commitment to designing healthcare facilities.

Christine Binswanger (CB): I also re-read Der Zauberberg recently and I thought the descriptions of Hans Castorp and his fellow patients lying out on the balconies – the sophisticated technique of how to wrap oneself in a blanket, recurring over 100 pages – were incredible. On the architecture more specifically, the section of the Schatzalp Hotel is indeed interesting as the floor of the balconies is higher than the level of the interior floor, allowing the sun to penetrate deeper into the rooms.

CAB: In your first built healthcare project, REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology (1999-2002, 2018-2020), the patients’ rooms have a deep veranda space which reminds us of such a genealogy. Was that a reference?

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

CB: The veranda was in fact one of the first architectural decisions that informed the identity of REHAB as a building that breathes and allows a seamless transition between outside and inside. But it wasn’t just us thinking of the sanatorium as a fascinating building typology: the client explicitly wanted the patients to be able to go outside as much as possible. Even when they’re bedridden, or in a coma, their bed can be wheeled onto the veranda, which I think expresses the spirit of this institution very well. Rehab is a specific typology because patients stay for extended periods, from a couple of weeks up to a year or more. Shading is needed to protect the veranda from the sun in the summer but, equally, because the beds have electrical components, you need to keep out the rain as well – imagine a sudden summer storm when the nurses can’t get everybody in at once.

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér -

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

The wooden rods of the balustrade, linked by Plexiglas dowels that reflect the light, are an element we applied in a variety of forms throughout the building. One thing triggered the next: while the patients’ rooms are fully glazed, the relationship with the outside is mediated by the deep veranda and the roof, which make the space feel cosier, allowing for views without the sense of being exposed. And since all this makes for a very deep space, we introduced ʻthe eye’ – a transparent plastic sphere cutting through the ceiling that brings additional light into the room and allows patients to look at the sky while they’re lying in bed. The influx of light is carefully controlled by built-in shading and blackout elements; additionally it acts as a lamp at night.

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

CAB: Was there also a conversation with the client about individual elements such as the balustrade or the window, beyond the general discussion about the program?

CB: Yes, we talked a great deal about all the elements, including the façade. We do this with every project, but the client for REHAB was particularly keen to involve all the different disciplines that were going to work in the hospital from the outset, during the competition phase. The chief medical director had very clear ideas, but at the same time was open to experimentation. He let us try out things that not everyone would have agreed to. For example, we told him that the wood outside was best left untreated: the window frames were coated with a sealant, but the rest of the wood was not, so it weathers over time. The director told us that the imperfections of the building are a good thing, because they somehow reflect the fact that these patients must learn to live with the imperfections of their bodies.

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

CAB: It sounds like there was a very productive engagement between your design team and the client.

CB: During the design process we made a 1:1 mock-up of a patient’s room. One might expect an architect to automatically know whether a space should be 240cm or 260cm high, but a mock-up is an important step when you’re experimenting, as we were here, with the curved ceiling, the skylight, and the veranda. It helped in balancing daylight, views, and privacy. Many clients don’t understand at first why we need to go through this process, because it clearly entails more work. It’s quicker just to do a 3D model and say: ʻDo you like it? Ok, let’s go with it.’

CAB: Herzog & de Meuron have for a long time engaged with typologies such as housing and museums, the latter also requiring particular attention to the control of light. Do you think this design path has informed your approach to the design of windows for healthcare facilities?

CB: Interesting question. Thinking about windows steering perception, we could talk about the Goetz Collection in Munich, which we realized a couple of years before REHAB. In order to maximize the wall space for the artworks, the windows were placed along the upper portion of the walls. More importantly, the clerestory windows allow a spatial experience that is identical on both floors, even though one floor is underground.

-

Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany, 1992: © Architekturzentrum Wien, Collection, photo: Margherita Spiluttini

-

Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany, 1992: © Architekturzentrum Wien, Collection, photo: Margherita Spiluttini

Perception has been central for both Jacques and Pierre from the outset. They’ve always collaborated with artists; I remember Rémy Zaugg coming into the office in my early days. He would work with us on drawings and if he couldn’t see what we were talking about, he’d say that it was not a good drawing. But he also taught us about the perception of space. I remember him walking along the outskirts of Basel during the urban study, ʻA nascent city? An urban study on the Trinational Agglomeration of Basel’, meticulously documenting what he saw: ʻA pond, a field, and in between a fence…’ Some of that fascination for ʻsimply looking’ has rubbed off on me. The window is of course a tool through which we perceive: it mediates the relation of the body to its environment, something that’s particularly important in the context of a hospital. For the patient’s room in REHAB, it was mainly about the bodily experience of lying in bed, while in the rest of the building it was about how it is to be in a wheelchair.

-

REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér

CAB: The window also brings in the aspect of time, the passing of the day and the seasons. And it helps with orientation, especially given the ever-increasing scale of hospitals nowadays. With your nearly completed Children’s Hospital in Zurich (2014-2024) you had to deal with a larger program…

CB: Orientation has a very high priority. When you’re in a hospital you’re already in a situation of stress, which only increases if you feel you don’t know where you’re going: too often, you end up in a badly lit space waiting for someone to come and take care of you. In such moments it’s important not to feel lost and forgotten. Our first series of hospitals, including the Children’s Hospital in Zurich, were conceived as horizontal buildings with only a few storeys, organized like small towns with main and side streets, squares and gardens. You can orient yourself via the courtyards, and have a view towards a tree while you wait, for example.

-

Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎ ARGE KISPI Herzog & de Meuron / Gruner

CAB: How do you define orientation via the courtyards? Is it by introducing a certain domestic scale, for example?

Raúl Mera (RM): The 16 courtyards in the Children’s Hospital vary in size and shape, so they always give you a distinct point of reference. Equally important for orientation is of course the layout of functions: here, the ground floor is the most public area, with the high-traffic zones of the hospital – emergency room, outpatient clinic, diagnostic and treatments, restaurant, access to therapies. The intermediate floor has additional day clinics in the centre, along the ʻmain street’; wrapping around these areas are the administrative offices, which are more private. The different functions of the two floors are legible in the variations of the façade, the concrete grid, and its timber and glass infill.

-

Mock-up of the Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎Herzog & de Meuron

CB: The openings change according to where you are, allowing for different degrees of privacy and publicness. For example, the treatment rooms on the ground floor have a deep façade, so passers-by never come too close. The windows are placed in the corner, not in the centre, so by the time someone registers the window they’ve already walked past it. The depth of the timber structure creates a sense of protection for the rooms behind, allowing the windows to be kept open a substantial part of the time. Since the intermediate floor is programmed as office space, the grid of the outer façade is regular. The ribbon windows allow for flexibility, and there are occasional balconies in front of common spaces. Everybody who has a desk in this institution is in this outer ring: 600 people from all departments. Above this, on the top floor, are the children’s wards, which are the most private spaces of all. The individual patients’ rooms have ʻclassical’ cut-out windows, one could say, which creates a sense of cosiness when combined with the individually tilted, deeply cantilevered roof and even an individually inclined drainpipe.

-

Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎Herzog & de Meuron

RM: The patients’ rooms are configured as little houses or ʻhuts’, with either one or two beds. They also have pull-out benches where parents can sleep when they stay overnight. In this case as well, we did 1:1 mock-ups to test the functionality of both the room and the bathroom, the different built-in and loose furniture elements, and lighting. There’s a large window framing the landscape, along with a small, operable, wooden ventilation porthole placed low on the wall, addressing the perspective of children. After all, this house is made for them.

CB: Indeed, making the building child-friendly was a key issue here. And instead of, say, painting giraffes on the walls, we tried to find architectural elements that speak to kids, that address their curiosity. For instance, with this small operable porthole in their private room, we thought they could put a teddy out there overnight and then take it back in the morning. Or there’s the main entry ʻgate’, which was slightly mystifying for the client when we first proposed it: we’re never closed! Indeed, the gesture might seem absurd, but given this very long façade, how do you find the entrance? The double-height element in concrete looks like an oversized barn door that has been fixed in its wide-open position – it’s an image that’s memorable for kids.

-

Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎Herzog & de Meuron

CAB: It’s impressive how you have these different kinds of openings with their own distinct qualities. Normally a hospital doesn’t have such variety; there tends to be just one kind of window that’s repeated over and over.

RM: The shapes of the inner courtyards also vary, as a result of different needs on three different floors. Each one is distinct, although we applied strictly repeating window types. These courtyards have a very urban character, like backyards, and all of them are landscaped. The glazed doors are completely standard, but the inclined sunshade structure and the slightly opaque coloured glass of the balustrade allow them to stand open while you’re having a treatment, or sitting in your office, and nobody will see you. These outside elements are not architectural fantasies but preserve intimacy in these ʻinner city’ courtyards that are just 7m deep.

-

Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎Herzog & de Meuron

And by the way, even the operating theatres have windows. They’re not for the surgeons – in fact, the window shades are down during operations, when you need controlled, high-intensity artificial light. Instead, the windows are for the people who clean these technical spaces throughout the day, to create a better environment while they’re working.

CAB: Cleaning and maintenance are indeed central aspects of healthcare environments. Is it easy to have that kind of timber-frame window in the context of a hospital building?

CB: In 20 years at REHAB none of the windows have needed replacing. As I mentioned earlier, the timber frames were sealed, but the balustrades were not: the wood ages and deforms a bit. It’s an aesthetic discussion and decision, not a functional one. Most hospital clients would prefer – not need – their hospital to look clean and sanitized from the outside as well. At the Children’s Hospital, the client appreciated the fact that the expression of the building was approachable and friendly – and not alienating. Obviously, different degrees of hygienic performance are required in different zones of a hospital. For example, an operating theatre must be surgically clean, but in a treatment room you can have a little table and it can be made of wood if you seal the surface – it’s not really an issue. That degree of variation, of complexity, of course entails more work – for all planners as well as for the users we design a hospital with and for. Quality means effort.

RM: All the timber surfaces in the interior had to be treated, and it took us a long time to find the right sealant as we wanted to maintain the expression of the wood, the grain, rather than cover it with a plastic-like resin or painted finish, for example.

-

Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, 2014-planned completion 2024 : ©︎Herzog & de Meuron

CAB: Your windows have a lot of layers and elements – sun shading, opening systems – which are operated in various ways. It’s quite surprising, as hospitals often try to control the interior climate very carefully and would never countenance the idea of an operable window.

CB: When it comes to the design of healthcare facilities we’re in a kind of ʻarchitect’s paradise’ here in Switzerland. We’re also working on a large hospital in the United States right now and the opportunity to open a window is limited. Of course, we cannot always open them here either, but generally we try to offer self-controlled fresh air wherever possible.

RM: Our main intention is to try to give a hospital a domestic feel, to make people feel comfortable and like the hospital, not fear it. There are about 2,000 rooms in the Children’s Hospital and a large number of variations within the entire structure. Partly it is our working method, which includes BIM modelling, that allows us to manage such complexity. But more generally, it is an openness towards innovation in this field, along with a readiness to work towards finding common-sense alternatives to the established rules when we ask ourselves the question, ʻHow do we do a hospital?’

Christine Binswanger

Christine Binswanger joined Herzog & de Meuron in 1991, became a Partner in 1994, and has been Senior Partner since 2009. She is responsible for projects in many countries, with particular focus in Switzerland, France, Spain, and the US. She has been in charge of many museum projects, including the expansion of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, USA; the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, USA, and the extension of the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar, France. The REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology in Basel, Switzerland, and the new Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, are notable examples of a number of hospital projects she leads. Her experience in urban development includes large civic planning projects in Lyon, France, and Burgos, Spain, as well as a large transformation project in the Dreispitz area of Basel, Switzerland. Housing projects she has led include the Rue des Suisses Apartment Buildings in Paris, France, and the Zellwegerpark in Uster, Switzerland. She was also in charge of the 1111 Lincoln Road project, a mixed-use structure for parking, retail, a restaurant, and private residence in Miami Beach, USA.

Binswanger studied architecture at the ETH Zurich from 1984 to 1990 and received the Meret Oppenheim Prize in 2004 in recognition of her active leadership in the architecture and art community.

Raúl Mera

Raúl Mera began his career in architecture in 1992 working as a draftsman, and completed his apprenticeship in 1996. He studied artistic design at the SFG, Schule für Gestaltung in Basel from 1997-2001 and returned to work as an architect in the Swiss offices Gigon/Guyer and Buchner Bründler from 2001-2008, at which point he received his diploma from the University of Applied Sciences, ZHAW Zurich with special honors. After his diploma Raúl worked as an architect at the office EM2N and Harry Gugger Studio, while teaching at ZHAW Zurich and acting as Design Support in the department for civil engineers at ETH Zurich. In 2017 Raúl Mera joined Herzog & de Meuron, focusing on developing construction detailing for the façade of the Kinderspital Zurich, the new Children’s Hospital. With this experience, he continues his work on hospital projects such as Universitätsspital Basel Klinikum 3, the University Hospital Basel.

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at ETH Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan’s Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba since 2009, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), and Columbia University (2017). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city through publications such as Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia. Awarded the Wolf Prize for Architecture in 2022.

Simona Ferrari

Simona Ferrari has been a teaching and research assistant at the Chair of Architecture Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) since 2017. She studied at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Technical University of Vienna, Politecnico di Milano, and Zurich University of the Arts. Her work engages with different scales and formats, from architectural projects to photography and text. She is the co-author of Landscape In-Between, a project for the former industrial site of Acetati in Verbania, Italy, awarded by the Europan competition in 2019. From 2014 to 2017, she worked with Atelier Bow-Wow in Tokyo, completing several international projects, exhibition designs, and installations. She is a recipient of the Monbukagakusho Scholarship and MAK Schindler Scholarship in Los Angeles.

Top image: REHAB Basel, Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology, Basel, Switzerland, 1999-2002, 2018-2020 : ©︎Katalin Deér