Between Hatakeyama and Sugiura

02 Mar 2023

- Keywords

- Columns

- Photography

Kokei and Jokei: Sights we see, scenes we feel

Whenever transparent glass is installed into buildings or trains or cars, a boundary is established, resulting in the creation of an inside and an outside. However, as light travels through the glass, it is able to deliver the scenery of one side to the receiving eyes of whomever may be on the other side. From bustling cities full of people to natural landscapes like mountains and oceans, such scenery that is gazed upon through the boundary of glass has been countlessly and continuously featured not just in photography but also in paintings, movies, and literature, to the point that it can be considered a cultural phenomenon. Mindlessly sipping on a coffee at a cafe, driving a car past a seaside, riding a train through an unfamiliar landscape; when fragments of such scenes suddenly come to mind and our emotions begin to layer themselves upon these otherwise completely normal views, we may find the scenery transforming into something poignant and unforgettable. With each passing moment, the view that exists on the other side of the glass delivers itself to us again. And at dusk, as the lights begin to twinkle here and there, the glass shows us, as only it can, an image of a world that contains both the inside and the outside, one that fades into the night like an elusive dream.

Slow Glass

What if what we see through the glass isn’t actually the world as it truly is? In his work Light of Other Days, the Northern Irish science fiction writer Bob Shaw writes about “slow glass”, which only allows light to pass through it slowly so that the image of the view on the other side arrives delayed. It’s quite interesting to see how the slow glass toys with human relationships, because it shows us the various ways in which memory and consciousness are connected to the visual image, but at this point one may realize– could “being seen belatedly” be a clever reference to the very essence of photography?

Up until recently, it was the norm for photographs to be taken on film. There was no way to immediately check the image that had been taken. Whatever was captured was stored temporarily on film, and only later would the image appear. There is a certain sort of irrevocability to this. Film’s material ability to create layers of time has long captivated people and has surely played a part in the discovery of various techniques and the overall enrichment of photography’s history. Even now, as the modern-day process of snapping lots of photos, immediately editing them, and showing them to someone has become a behavior shared by many, a certain gap still exists between the real life subject and its photographed likeness, and as new apps continue to be updated daily, this gap stretches and shrinks. As Hatakeyama describes in his essay, the duality of the photograph to be “both a mirror and a window” may have been one of the sources of the fundamental conditions of photography.

One of Hatakeyama’s works is inspired by this idea of slow glass. “Slow Glass / Tokyo”, which was featured on Hatakeyama’s text in the first article of this series, is part of his series of photographs of Tokyo that were taken with a self-made camera. The camera is covered by a box with a window that is designed to catch the camera’s focus. When the camera is taken out into the city on a rainy day, the raindrops that stick to the window invert and multiply the scenery endlessly. Like mirrors, they reflect the scenery inwards back towards the outward-facing camera window, creating a meta-photographic moment that conveys the dual nature of photography. Wedged within the fissures of this paradox, one gets the feeling one will find the fundamental essence of the transient human memory, its ebb and flow just like that of the glowing, trickling raindrops.

To Kunié Sugiura

The next writer in this series of articles will be the artist Kunié Sugiura. Sugiura moved to the U.S. in 1963 to study at the Art Institute of Chicago, and has now based her practice in New York for over 50 years. Over the course of our correspondence, she told me that she had seen the “Mirrors and Windows – American Photography since 1960″ exhibition in person at the MoMA (the one Hatakeyama had seen through catalog as a college student) and she recounted to me that after seeing the show, she “remembered thinking that photography is not so easy.” Based on the fact that Hatakeyama had mentioned this show, and my intuition that Sugiura, who is also an artist working within the medium of photography, must have seen this exhibition in person, I reached out to her to request her to write an article.

The period covered by this exhibition is 1960, and the year the exhibition was held was 1979. In a magazine interview, Sugiura once said, “New York at that time had speed, a real sense of being alive. The hippie movement had reached its peak and the world seemed as if it was getting better and better, but at the same time the Vietnam War was going on, the youth were feeling a sense of looming crisis as their vision of utopia collapsed, and the influence of drug culture was strong.” One can imagine how difficult it must have been for Sugiura, who is neither male nor Caucasian, to work as a female artist in New York at that time. I would like readers to note that this was the backdrop against which this exhibition was held.

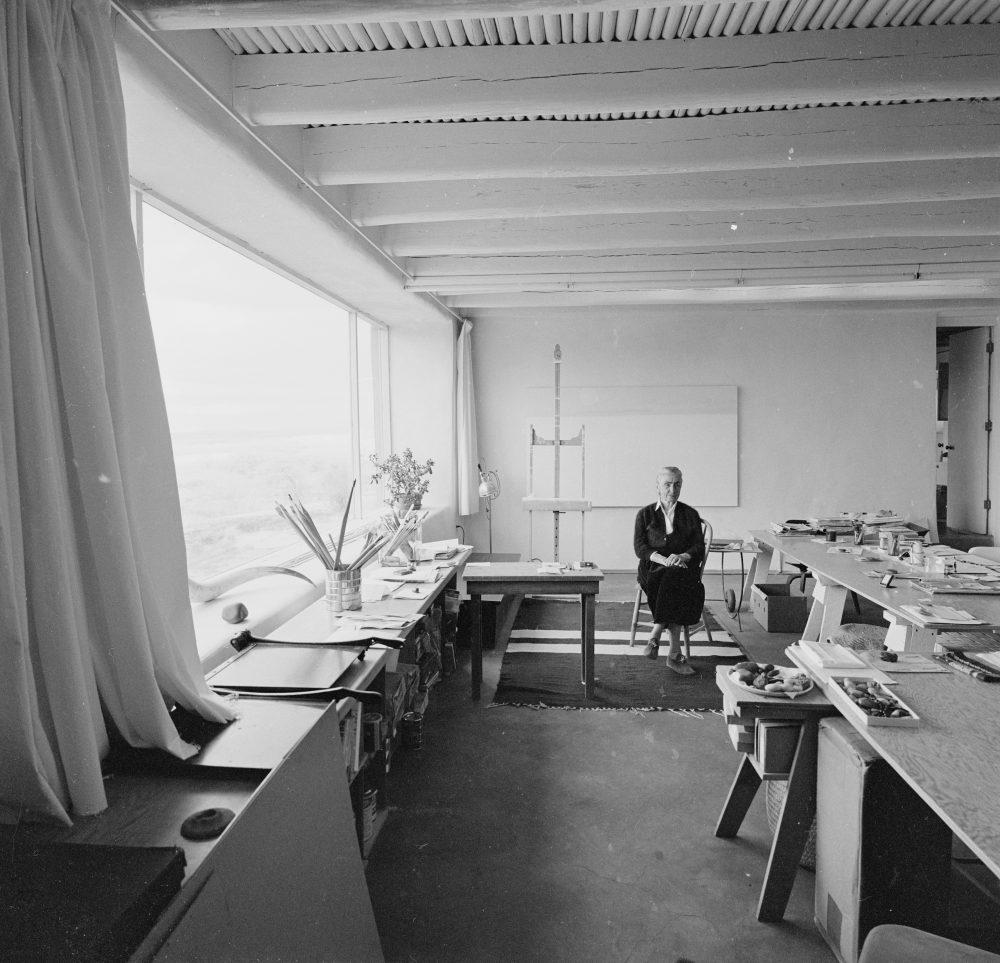

There is one more reason why I wanted to feature Sugiura in this series. I’ve visited Sugiura’s studio in Chinatown, where she has been based for decades, on two occasions, and I couldn’t forget what I saw there. To say it simply– I had never visited such a beautiful studio before. The door opened up to a room so spacious that it seemed to pull open my field of vision, and in the corner, an arrangement of artworks were lined up randomly; between these was a run-down couch and a bed with a cover thrown over it that seemed to be there just for visitors. A number of in-progress works hung on the wall.

The room was located in a former theater, an old building that was built around 100 years ago, with thin, clouded glass that faced the street. The outside noise of the Chinese restaurants and other businesses lining the bustling street filtered into the room.

Photographs developed on canvas combined with acrylic-covered canvases and fitted into wooden frames. These pictures of places in New York, complemented with symbolic color surfaces and framed in wood, seemed to me like a window discovered from within the depths of the enormous mystery that is the city.

Yutaka Kikutake

Yutaka Kikutake was born in 1982 and graduated from the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Waseda University. After working for Taka Ishii Gallery, he opened his eponymous gallery in the summer of 2015. He is also the publisher and editor-in-chief of the lifestyle and culture magazine 疾駆/chic. Through the two platforms of gallery and publication, his projects aim to strengthen and enrich the connection between art and society.