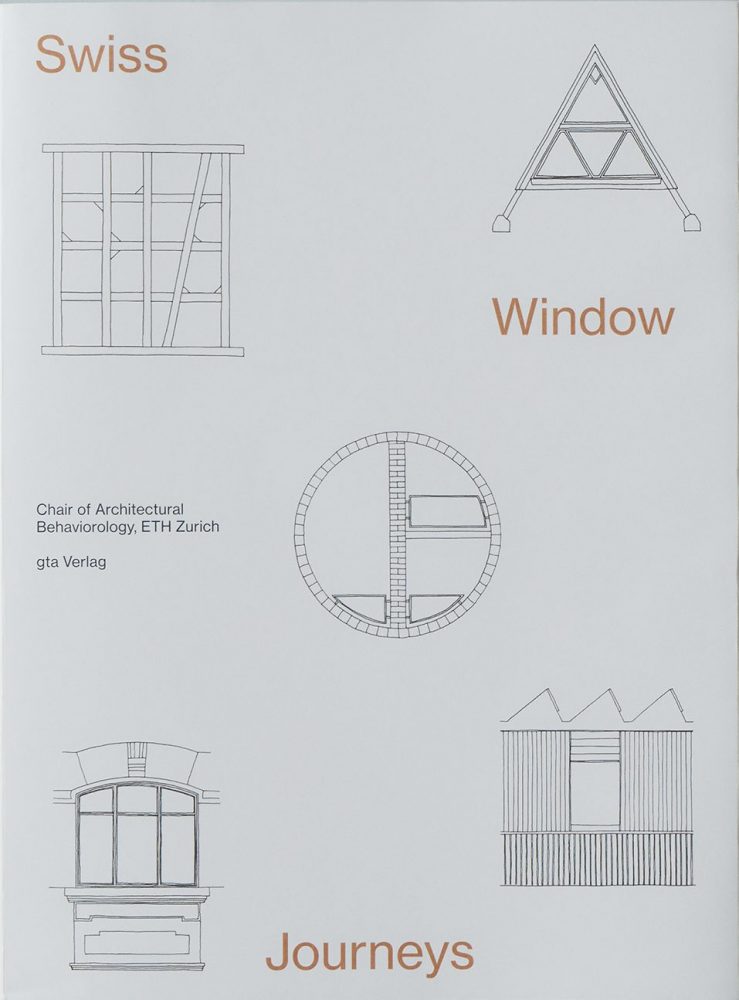

Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Conversation with EMI Architekten

15 Dec 2022

Ron Edelaar, Elli Mosayebi, and Christian Inderbitzin founded EMI Architekten in Zurich in 2005. The office has developed a particular focus on housing and urban design in Switzerland through numerous projects awarded via competitions. Parallel to their practice, research and teaching have been critical aspects of their endeavours, and Elli Mosayebi has been a Professor for Architecture and Design at ETH Zurich since 2018. To learn about their projects and approach to designing windows, the Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) spoke with Mosayebi and Edelaar at their studio in Zurich.

Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (CAB): With your practice you’ve been working on numerous housing projects in Zurich and its surroundings, experimenting with a variety of living conditions. Yet, with spatial planning laws in Switzerland pushing for greater densification in urban areas, providing for a high quality of life in residential buildings has become increasingly challenging. We’re interested to discuss the role the window plays for you in this context, as well as, more generally, the way we use this building element that seems to have become less expensive, but more highly regulated and standardized.

Elli Mosayebi (EM): I think that when we talk about windows, our starting point is generally the beauty of the floor plan. A fascination with the floor plan is something we’ve inherited from our studies with Peter Märkli at the ETH. For us, windows are an organic part of the plan; they play a crucial role in how you move through the space of the apartment and what you perceive as you do so. How the facade plays out is an important topic as well, but in our office we really emphasize this aspect of interiority. Then the role of the windows depends on the individual project. We could tell you a different story for each of them.

In the case of the Steinwies residential building in Zurich-Hottingen, for example, how you enter the apartment is extremely important. It’s a slow, inverted progression from inside to outside, from the darker interior space of the entrance hall, to the elevator, and from there into your apartment and a room lit by three windows.

The construction of these windows is rather simple. They’re casement windows, with a metal and timber frame, and their only special feature is the pivot hinge fixed to the top and bottom of the frame (rather than the side), which allows each casement to open. Pivot hinge windows are another thing Peter is keen on: I can still hear him say that word, Zapfenbandfenster. And Christian and I also lived for six years in an Ernst Gisel apartment building in Hegibachstrasse which had these windows. That was certainly formative.

-

EMI Architekten, Steinwies residential building, Zurich-Hottingen, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

-

EMI Architekten, Steinwies residential building, Zurich-Hottingen, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

Ron Edelaar (RE): Usually in Switzerland apartments are organized on a single floor, as a horizontal sequence of rooms. There are a lot of conventions and client expectations, such as the typical wooden floor and the white walls. But windows and doors are two elements we can work with: they define how we move from one room to another and how we establish a connection with the world outside. The Geibelstrasse residential building, for example, stands at an intersection, in an open urban situation; it relates to both the street and the neighbouring buildings. In this kind of context, we like to provide for a measure of privacy with windows that are oriented either inwards or outwards, building on the Zurich tradition of bay windows.

EM: So on the one hand we have the more representative front facade, which has double bays that point outwards. And then, as Ron mentioned, we have this kind of negative bay window on the sides, consisting of two casement windows and a door. Both work together to define the connections between adjacent rooms. We also thought it would be interesting to have the rooms open out over the corners, generating oblique views over the street or the garden, but at the same time to have a density there, in the form of the door. In the end, the building expresses its own specific identity, but blends in with its neighbours because it has a similar scale and massing.

-

EMI Architekten, Geibelstrasse residential building, Zurich-Wipkingen, Switzerland, 2014-17 : ©︎Roland Bernath

-

EMI Architekten, Geibelstrasse residential building, Zurich-Wipkingen, Switzerland, 2014-17 : ©︎Roland Bernath

We also have this idea of negative and positive bay windows in the Speich Areal residential and commercial development. The building is on a busy road, so in this case the bay windows are partly about noise reduction, but they also give a rhythm to the facade. Again, too, there’s the idea of establishing a connection between inside and outside, with the window offering different views from within the same room.

-

EMI Architekten, Speich Areal residential and commercial development, Zurich-Wipkingen, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

-

EMI Architekten, Speich Areal residential and commercial development, Zurich-Wipkingen, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: It seems that the wall and the window are equally important in your design process. There is no hierarchy, say, with the wall coming first and the window then being punched out of it…

EM: I don’t think we’d ever draw a wall without a window: the opening is always there on the sketch. The Speich Areal building, for example, has a skeleton frame, which would theoretically have allowed for larger openings. Instead, they’re more of a hybrid – ribbon windows for the offices in the front part of the building, but a kind of punched window for the apartments, to provide more privacy for the living spaces. Hiding the skeleton behind a sculpturally pronounced, almost monolithic-looking structure creates an interesting tension between inside and outside. We like the ambiguity of expression and the openness of form.

RE: Another riff on the theme of windows and doors is the Freihofstrasse residential building, which contains affordable four- and five-room apartments of a rather modest size by Zurich standards. The entrance to the apartments leads directly into a spacious hall, which doubles as the kitchen and the dining room. Likewise, the living room can double as a bedroom if required. This explains the pronounced chambering of the floor plan. All rooms can be closed off with a door. They differ only minimally in size. What distinguishes them are their doors – as can be seen from the pair of doors on the back wall of the kitchen. One of these doors leads to the living room and is room-high and 80cm wide. The door into the room right next to it is 2.0m high, 1.0m wide, and has a lintel. Through the obvious difference in their dimensions, the two doors take on a distinct, anthropomorphic form. This character is reinforced by door handles of varying heights: 95cm for the narrow, tall door and 115cm for the small, beefy one. The height of the handles is in inverse proportion to the height of the doors.

-

EMI Architekten, Freihofstrasse residential building, Zurich-Altstetten, Switzerland, 2015-19: ©︎Roland Bernath

-

EMI Architekten, Freihofstrasse residential building, Zurich-Altstetten, Switzerland, 2015-19: ©︎Roland Bernath

Just as columns were assigned not only human proportions, but also ʻhuman characters’, the two doors are also given their individual characters. We compared them to Laurel and Hardy, a duo remembered more for their expressiveness than their elegance.

The window frames have the quality of a piece of furniture that can be used in different ways. There is a horizontal element that works like a shelf and gives you something to lean on while standing and looking out of the window. The slight slope of the lower reveal is technical: it prevents someone from climbing up, but it also brings more light to the floor. So in a way, everything has multiple meanings.

-

EMI Architekten, Freihofstrasse residential building, Zurich-Altstetten, Switzerland, 2015-19: ©︎Roland Bernath

EM: For us doors and windows are similar elements: in one sense, the window could be seen simply as a variation of the door. In both, the scale that they bring to the room is very important. But there’s also the questions of how they relate to the body, how light or heavy they are, how they’re used, what kind of material they’re made of, whether it’s precious or not. All these aspects have different meanings and influence the everyday experience of life.

CAB: Could you tell us a bit more about the pivot hinge window (Zapfenbandfenster) you mentioned earlier?

RE: The Zapfenbandfenster is somewhat forgotten in Switzerland. It seems to have vanished around the 1960s, when the window industry took off. Up to then, there weren’t set standards. Architects would design their own windows and a joiner would produce them. We’ve reclaimed this invention, having found a window fabricator who still knew how to make one. What we like is that it’s not abstract, in the same way as a sliding window, for example. Rather than having a single large window, you can have several vertical windows in a row, each one of which can be opened in any way you choose.

-

Zapfenbandfenster: BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Residential building in Katzenbach, Switzerland, 2012-19 : ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: Are your windows based on standard dimensions, perhaps also for budget reasons?

RE: For us, the size of the window is a question of proportions and of the dimensions of the human body, rather than something to be determined by industry standards. Traditionally in Europe we have different proportions. In Switzerland we make widespread use of the vertical window – a kind of French window, really. There is also a technical consideration: when casements are larger, they’re harder to stabilize when they’re cantilevered.

Regarding the cost, the situation has changed a great deal since we began our practice. Ten years ago, a window was something precious and expensive, today it’s relatively cheap. For example, in our Schwamendinger-Dreieck housing, the windows cost less per square metre than the facade. This also has something to do with the detailing of the windows, which extend from floor to ceiling, with the floor slabs effectively functioning as lintels. Here the fixed glazing at the bottom of the windows is made with reinforced glass, eliminating the need for a balustrade. The fewer pieces you have, the lower the costs.

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Schwamendinger-Dreieck housing, Zurich-Schwamendingen, Switzerland, 2014-23 : ©︎Roland Bernath

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Schwamendinger-Dreieck housing, Zurich-Schwamendingen, Switzerland, 2014-23 : ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: We could imagine that the decision to have the window extend the full height of the wall, besides its practical motivations, must also have an impact on the way people inhabit the apartment and arrange their furniture…

EM: Very much so. When we work on floor plans they are always furnished, but we develop them in a way that allows for a certain degree of appropriation. When we visit our buildings after they’ve been occupied for a while, we sometimes see them being used differently to how we imagined, which we find quite ok. When someone puts a sofa in front of a full-height window, it’s no problem – we’ve done that too!

But something we always bear in mind is the need to bring the different scales together – the room, the building, the larger urban setting. So we could say that the window also corresponds to an urban idea. For example, in the Schwamendinger-Dreieck housing the slight offsets in the facades are a response to the urban setting. These offsets, a kind of adaptation of the bay window, give every apartment oblique views to the north and south, in addition to the primary east–west orientation of the living space. So everyone can have a complete sense of their surroundings from within the apartments.

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Schwamendinger-Dreieck housing, Zurich-Schwamendingen, Switzerland, 2014-23 : ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: As the city of Zurich becomes increasingly densified, with more people living in close proximity to each other, these diagonal views – as opposed to frontal views – offer an interesting way to establish a connection with the city while avoiding conflict…

EM: Maybe it’s less about avoiding conflict, and more about expanding the field of vision in this denser situation – allowing views deep into a housing estate, or a garden. If you can direct the eye not just to the points nearby, but also to elements that are further away, somehow it makes the apartment appear more spacious. In every project the relationship of the building with the garden, with the external landscape, is extremely important for us. And of course this has to do with densification: as the pressures on free space increase, it acquires even greater value.

CAB: So, despite the densification of the programme, such attention to the surroundings, through the device of the window, allows for better living conditions.

EM: Responding to a given situation is actually a wonderful opportunity: very often, it’s where we get our ideas for the form of our projects. How to then balance this form with the required density is something that’s implicitly quite important for us. To achieve a coherence between the floor plan and the urban situation is an important goal in almost any project. The Guggach residential complex, for example, lies in a transitional area, between the inner-city fabric and the district of Oerlikon. It used to be not so dense around here, but the site now lies in the centre of a larger development area, with a forest to the west, existing housing to the south, new projects planned to the north. In response to this situation we invented a cruciform floor plan, cut at two points with loggias, which opens the buildings to their surroundings on all sides, to the views of the forest, the rooftops of the city, the other parts of the development – the facades and the windows weave together all these different experiences. The cross-shaped plan, oriented in four directions, allows the spaces of the interior to expand transversally, giving them a more generous feel, while the overall configuration of the buildings – strong, high, elegant volumes, with plenty of green space between them – helps to define an identity for the development and, with it, a sense of community. When you have this huge number of apartments – there are around 200 here – you have to somehow provide for a certain cohesiveness.

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Guggach residential complex, Zurich, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Guggach residential complex, Zurich, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

In contrast, our early Brüggliäcker housing was in an area of relatively small-scale development, with single-family houses and row house estates from the 1950s. To fit the context, we worked with three-storey elongated volumes, finger-shaped, with large loggias that extend the living space and connect it directly to the surrounding green space. The loggias are equipped with curtains on rails that can divide the space or close off the volume.

-

BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Brüggliäcker housing, Zurich-Schwamendingen, Switzerland, 2009-14: ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: It seems that incorporating these loggias or balconies is another important aspect of your approach. Are these elements also stipulated in the brief?

RE: Yes, these outdoor spaces are often a component of the programme, even if the climate here in central Europe means they can only really be used for three or four months a year. For this reason, we’re trying to question – expand – their traditional role. I think it’s interesting to think about winter gardens, rooms between the inside and the outside, that can be used all year. We’ve worked with this idea in our recently completed Schulstrasse residential building in Pfäffikon, for example. There’s no heating or water in these rooms, so they don’t have to be calculated in the square meterage. People can use them in different ways, including as a balcony, since all the windows can be fully opened.

-

EMI Architekten, Schulstrasse residential building, Pfäffikon, Switzerland, 2018-21 : ©︎Roland Bernath

CAB: Elli, you’ve written your doctoral thesis on the work of the Milanese architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni. Starting in the years immediately after the Second World War, his practice largely engaged with the design of living spaces in Milan during a period of rapid change, both in the dense fabric of the city and in techniques of industrial production. We imagine that his windows also define a specific relation to the context he was working in.

EM: Caccia uses windows in an extremely precise way, to frame particular views from inside, views of churches, of the Duomo di Milano, for example. He invents his own details – it’s always quite amazing to see what he comes up with. Very roughly, you can distinguish two types of residential buildings in his oeuvre. On the one hand you have the buildings in the inner city, which are very contextual, careful to establish continuity in terms of their facades, colours, elements and proportions. One example is the building in Piazza Sant’Ambrogio.

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Residential building in Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, Milan, 1948 : ©Elli Mosayebi

Then there are the buildings that are more on the outskirts of Milan, like the ones in Via Nievo or Piazza Carbonari, which are, let’s say, more futuristic. His clients were mainly the Milanese haute bourgeoisie – financiers, industrialists – who were driving the city’s economy at the time. Caccia became the architect of this postwar elite, giving them a particular identity through architecture. Again, he was quite inventive with details. He incorporated his great constructive knowledge of old palazzi into his new buildings and windows.

He was looking for a way to express the renewed self-image of this middle class through architecture. In the postwar period, the construction methods for these residential buildings were still artisanal, the elements were never standardized or mass-produced, even if they sometimes looked like they were. Caccia drew the detail and a carpenter or metalworker fabricated it for him.

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Residential building in Piazza Carbonari, Milan, 1960-61 : ©Elli Mosayebi

CAB: We could imagine that your research on Caccia has left a mark on your own work, perhaps influencing how you approach the design of housing and its relationship to the city.

EM: The influence of Caccia is a question that comes up a lot, especially in relation to our Steinwies project in Zurich-Hottingen. But I would say the strongest point of connection – and one that was shared even before the research – is probably the love for the floor plan. We like to think of our residents as flaneurs in their apartments, seeing and experiencing different things as they walk through their rooms. Surprise, entertainment create richness and variety. Ultimately, this doesn’t require much space at all, but rather the will to design many scenic and memorable moments.

-

Interview at EMI’s office in Zurich

-

full size window mock-up traced on the wall at EMI’s office

Edelaar Mosayebi Inderbitzin Architekten

Ron Edelaar, Elli Mosayebi, and Christian Inderbitzin founded their architectural firm in Zurich in 2005. The firm’s broad scope of work encompasses building projects – from design to construction – and urban planning along with exhibitions and publications. Housing represents a main focus of their research, teaching, and practice. In addition, major projects have been realized through routine collaboration with Baumberger & Stegmeier Architekten since 2011. Ron Edelaar, Elli Mosayebi and Christian Inderbitzin were enrolled as members of the Federation of Swiss Architects in 2014.

Christian Inderbitzin has been Professor at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology since 2020, he taught at the EPF Lausanne in 2015/2016 and, together with Elli Mosayebi and Ron Edelaar, at ETH Zurich in 2017/2018. Elli Mosayebi has been Professor for Architecture and Design at ETH Zurich since 2018. From 2012 until 2018 she was Professor for Design Housing at TU Darmstadt. Ron Edelaar has been a lecturer in constructive design at the ZHAW Winterthur since 2020.

http://www.emi-architekten.ch/

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at ETH Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan’s Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba since 2009, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), and Columbia University (2017). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city through publications such as Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia. Awarded the Wolf Prize for Architecture in 2022.

Simona Ferrari

Simona Ferrari has been a teaching and research assistant at the Chair of Architecture Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) since 2017 and works independently as an architect and artist. She studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, TU Vienna, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology as Monbukagakusho Fellow. From 2014 to 2017 she worked with Atelier Bow-Wow in Tokyo, completing several international projects. She is currently pursuing an MA in Fine Arts at the Zurich University of the Arts. Ongoing projects include the winning proposal of Europan 15 for the former industrial site of Acetati in Verbania, IT (with Metaxia Markaki).

Top image: BS+EMI Architektenpartner, Guggach residential complex, Zurich, Switzerland, 2011-15 : ©︎Roland Bernath

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Swiss Window Journeys: A Conversation between Andrea Deplazes, Laurent Stalder, and Momoyo Kaijima

17 Dec 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Silke Langenberg

25 Jul 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with François Charbonnet (Made in)

25 Jan 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Christine Binswanger, Raúl Mera (Herzog & de Meuron)

24 May 2023