Windows of the Prouvé House|Jean Prouvé’s Windows #2

22 Oct 2021

The Prouvé House is an intriguing example of a building that was made by piecing together leftover parts from past projects. In the second article of this series, Shin Yokoo examines how Prouvé incorporated ideas from his earlier work into his home and breaks down the designs of the windows that are unique to this project.

Was Prouvé an Architect?

Jean Prouvé was an autodidact in architecture and was never formally licensed as an architect in France. This was part of the story behind why he always collaborated with other architects. Moreover, his wide-ranging collaborations on works from furniture to architecture led to further blurring his classification as an architect or structural engineer. He has hence been labeled in a variety of ways. Most famously, Le Corbusier wrote about him as follows in Modulor II: “And here is M. Jean Prouvé who represents, in a singularly eloquent manner, the type of the ʻconstructor’—a social grade—not yet accepted by law but actively wanted by the era in which we live.”1 Reiko Hayama, a Japanese architect who worked for Prouvé, also translates the word “constructor” using the neologism “kōchikuka” (構築家, constructor), as opposed to “kōzoka” (構造家, structural engineer) or “kenchikuka” (建築家, architect), in Kōchiku no hito, Jan Purūve [original title in French: Jean Prouvé: Par Lui-Même]. Kenneth Frampton, who was early to point out the progressiveness of Prouvé’s work, refers to him as an “artisan/engineer” in Modern Architecture.2 However he may be described, there was only one building project that Prouvé planned, designed, and constructed on his own in the manner of a true architect during his lifetime: the Prouvé House (French: Maison de Jean Prouvé), his private residence in Nancy. As it happened, he undertook the project immediately following his departure from what was his personal factory and the base of his creative activities.

Reassembled Components

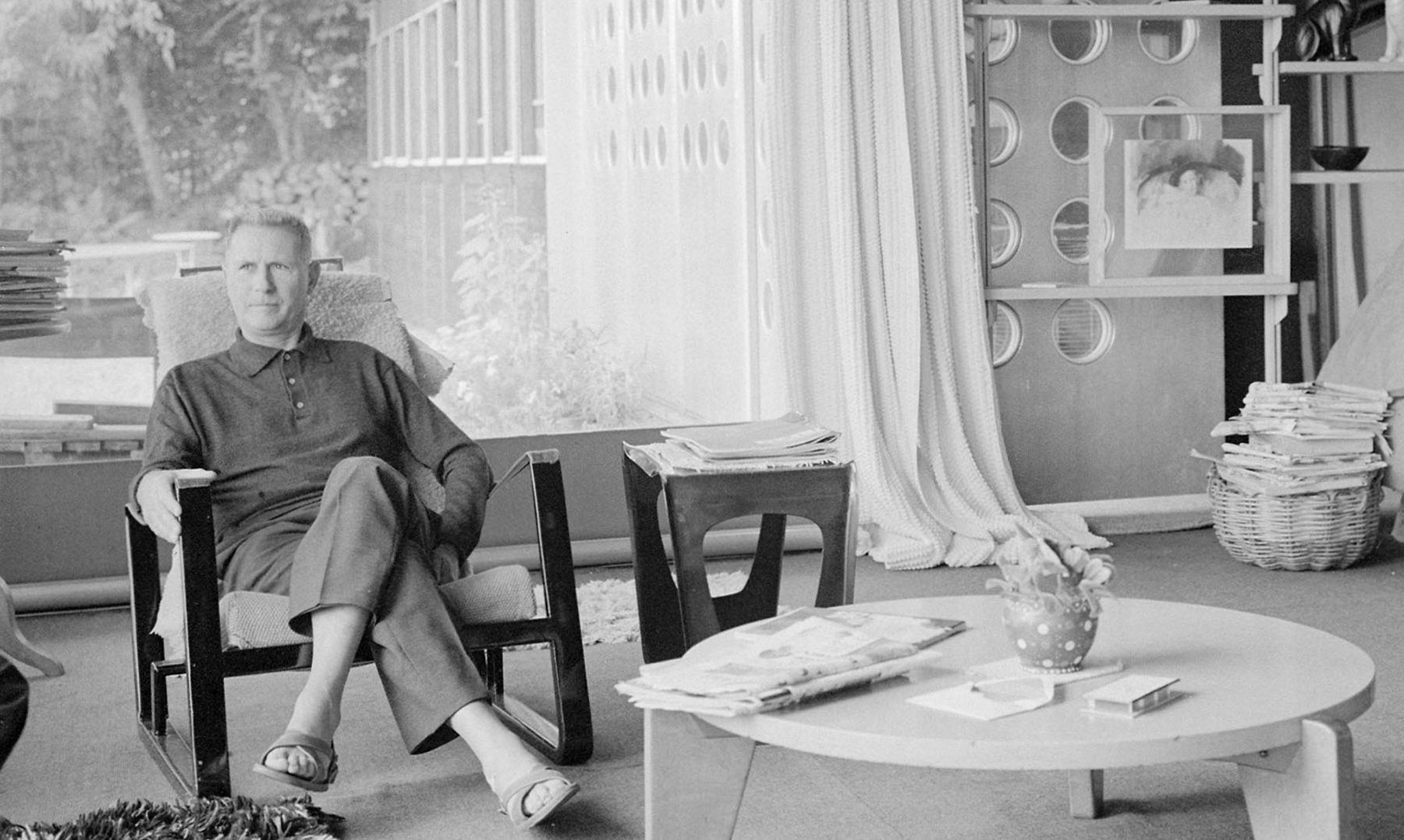

In March 1954, Prouvé was driven out of the former Ateliers Jean Prouvé and his factory in Maxéville where he had worked for 23 years. This turn of events was what led him to build a new home for himself, as he came to the idea to do so by reusing components of his own design that had been lying in a corner of the factory, waiting to be thrown away. He started on the construction of the house after his former colleagues smuggled the components out of the factory by truck. By using what could be described as “leftovers” and relying on intuition alone, Prouvé improvised a design on site and made himself a comfortable home with his family. He would however later receive a bill from Studal that listed the components intended for disposal at a “customary discounted price” (which was actually rather hefty). The site of the house, which is located midway up a hill about 25 minutes away from Nancy’s train station by foot, was believed to be impossible to build on due to frequent landslides. Notwithstanding, Prouvé purchased the property in May 1954 and managed to complete his home in just three short months from June to September.

-

Jean Prouvé ©︎ ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2021 E4396

Photo ©︎ Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Fonds Cardot et Joly / distributed by AMF

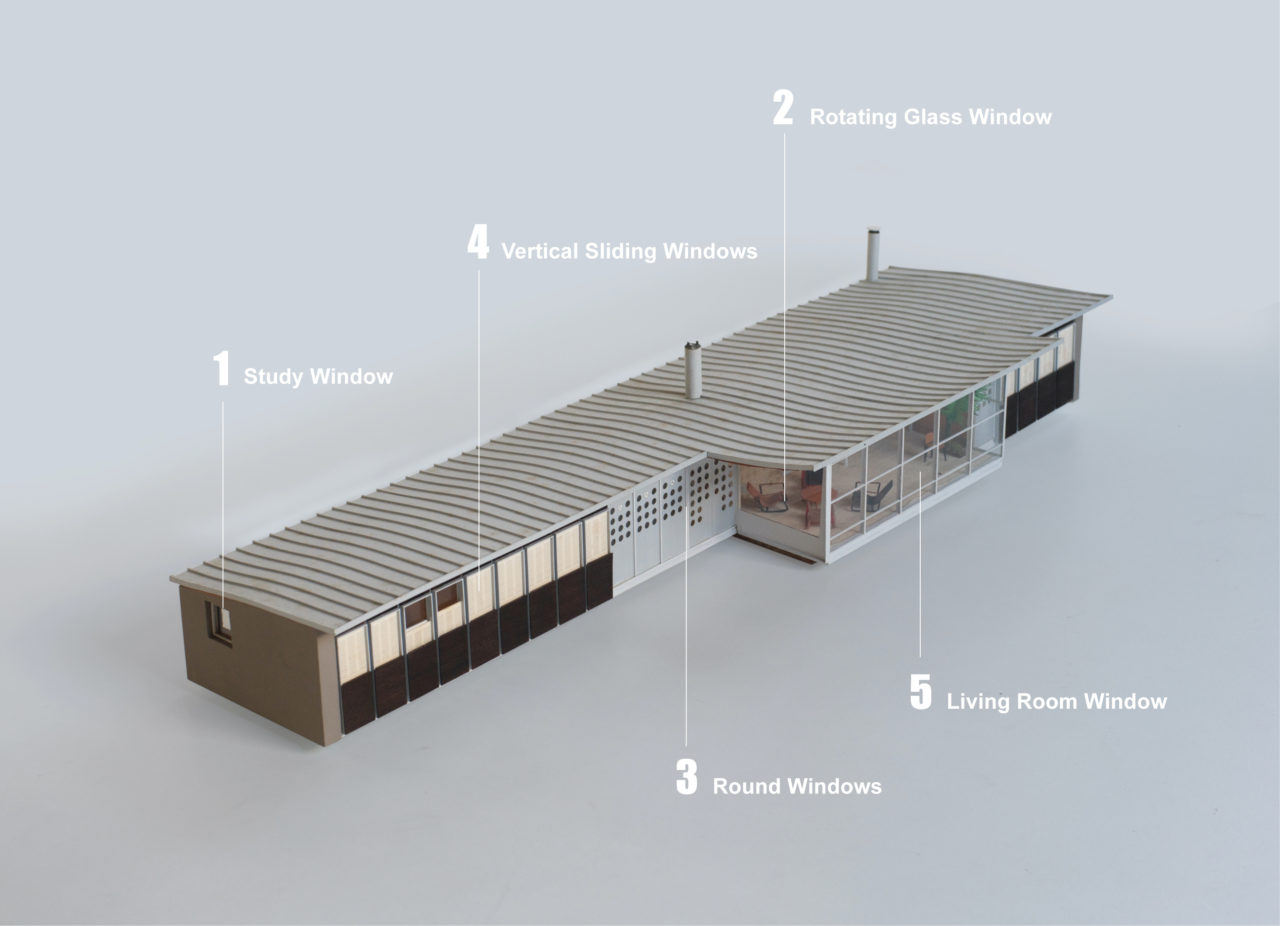

Five Distinctive Windows of the Prouvé House

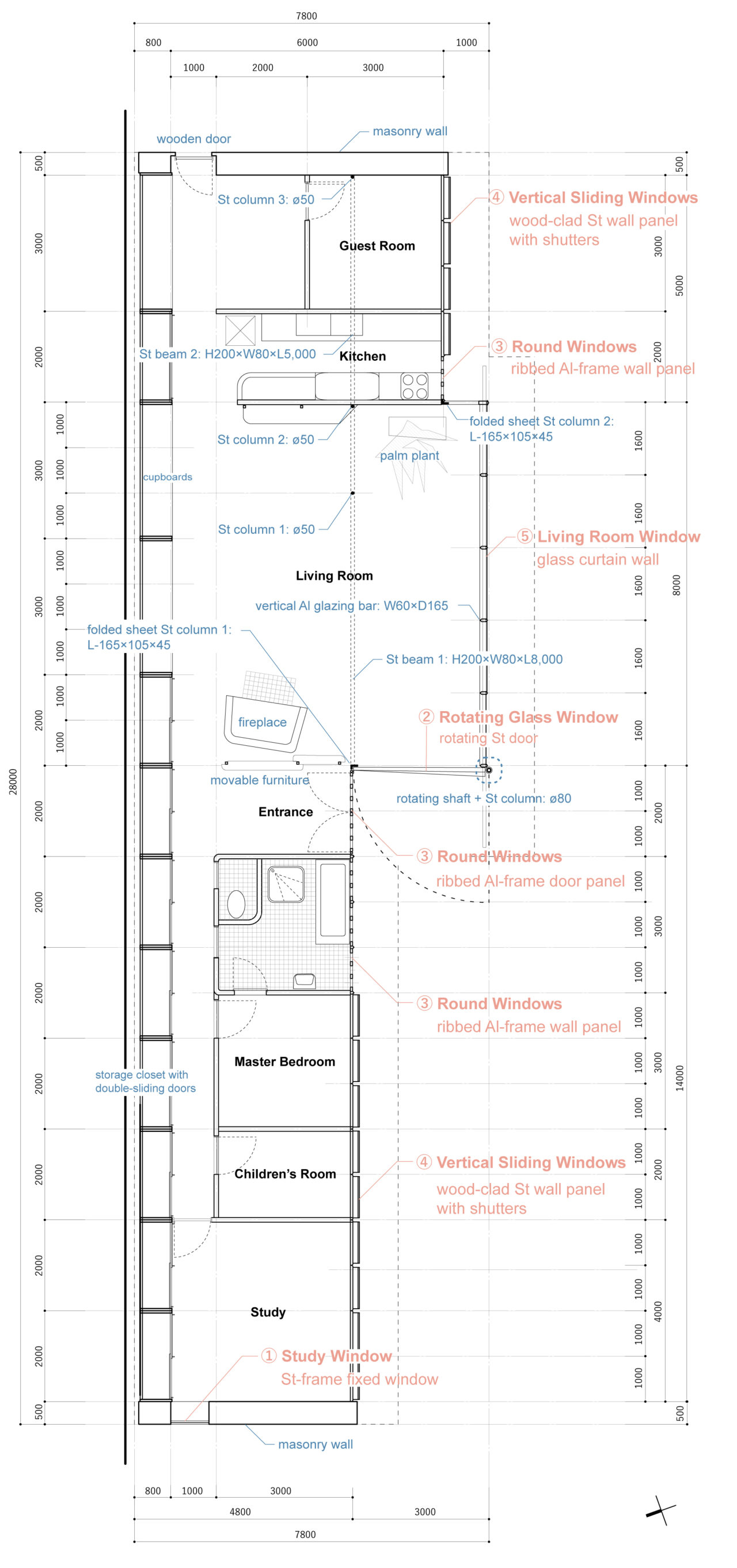

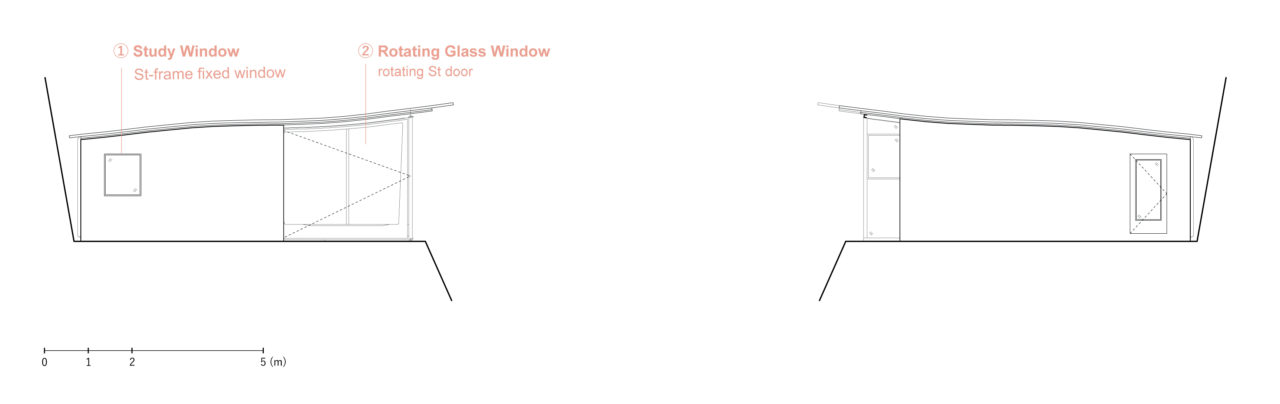

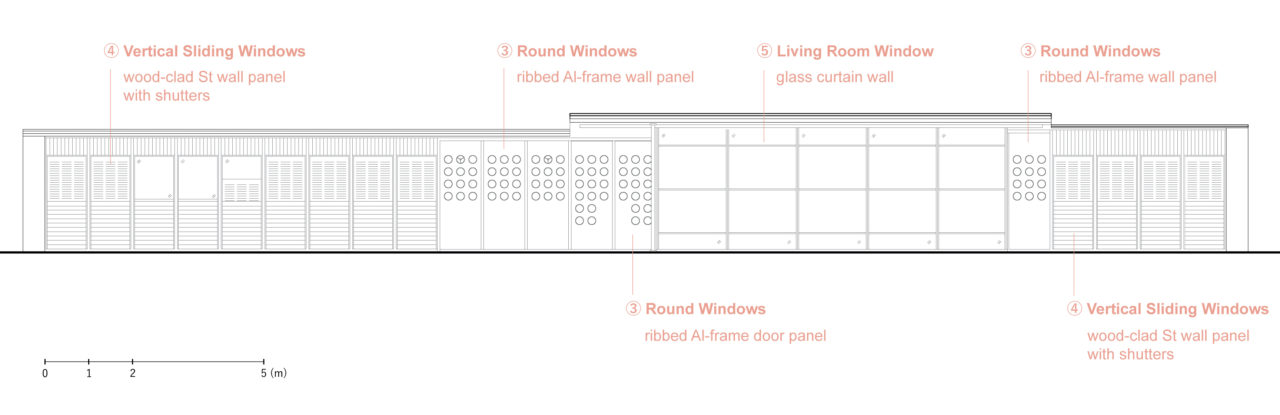

The Prouvé House is a long single-story building that extends out in the east-west direction with a northern elevation formed by a solid wall and a southern elevation that shifts in and out. Its façade that opens up to the south in response to the surrounding environment is composed of a large central glass window and one-meter-wide secondary components featuring a variety of distinctive windows that also respond to the interior layout.

-

Plan

Window #1: Study Window

The study, the outermost of the private rooms at the western end of the building, has a masonry wall with a small window in it. In an early scheme for the house, the window was designed as a door that would have established a symmetrical relationship with the wooden door at the house’s east end and provided a transverse circulation path for one to move from the outside to the inside (through the corridor) and back outside again. The fixed window that was ultimately built to bring light into the corridor from the west is set in a slightly oblong and likely reappropriated steel frame measuring 850 millimeters in width and a little under one meter in height. In addition to acting as a guiding beacon at the end of the 27-meter-long corridor and establishing a line of sight that pierces through the building along its internal axis, the window also creates an appealing contrast with the bare stone wall.

-

Jean Prouvé ©︎ ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2021 E4396

Photo ©︎ Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Fonds Prouvé

Window #2: Rotating Glass Window

This window, which measures three meters in width and curves down gently from a height of three meters to 2.5 meters following the profile of the roof, is the only window that was made originally for the Prouvé House. It was assembled by welding together three-millimeter-thick folded sheet steel. With cylindrical hinges built into the top and bottom of the post at its southern edge, it is also designed to be operated as a vertical-axis rotating steel door, and it hence has no window frame. In addition to acting as a rotating shaft, the 80-millimeter-diameter post made of 4.5-millimeter-thick steel serves double duty as a structural column for supporting the roof. This detail, which is perhaps easier to picture if referred to as a pivot hinge, was the first that Prouvé patented in 1931, when he was 30 years old. The opening was intended to be used as a secondary entrance for welcoming guests directly into the living room on days with good weather. Upon completion, however, the window’s eight-millimeter-thick single glass pane broke during use, and this led to a glazing bar being added.

-

West and east elevations

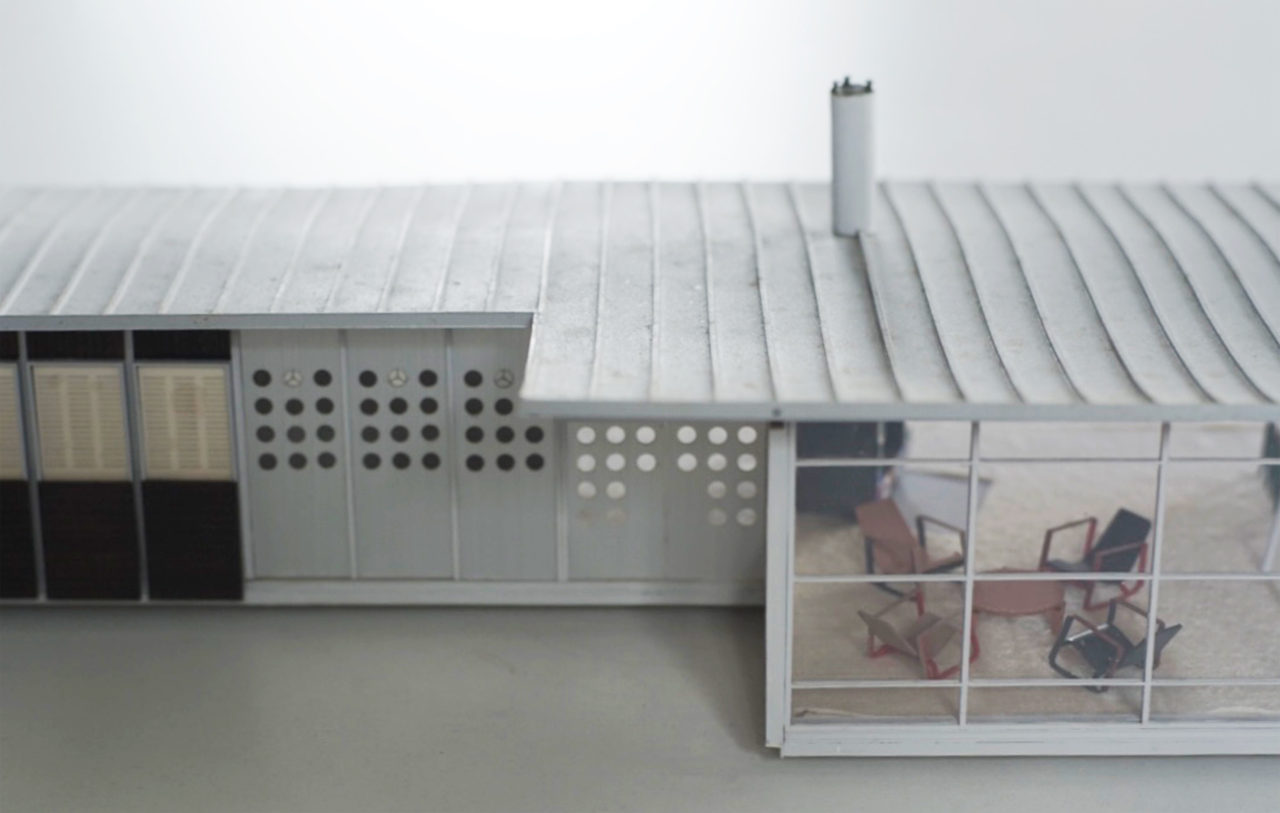

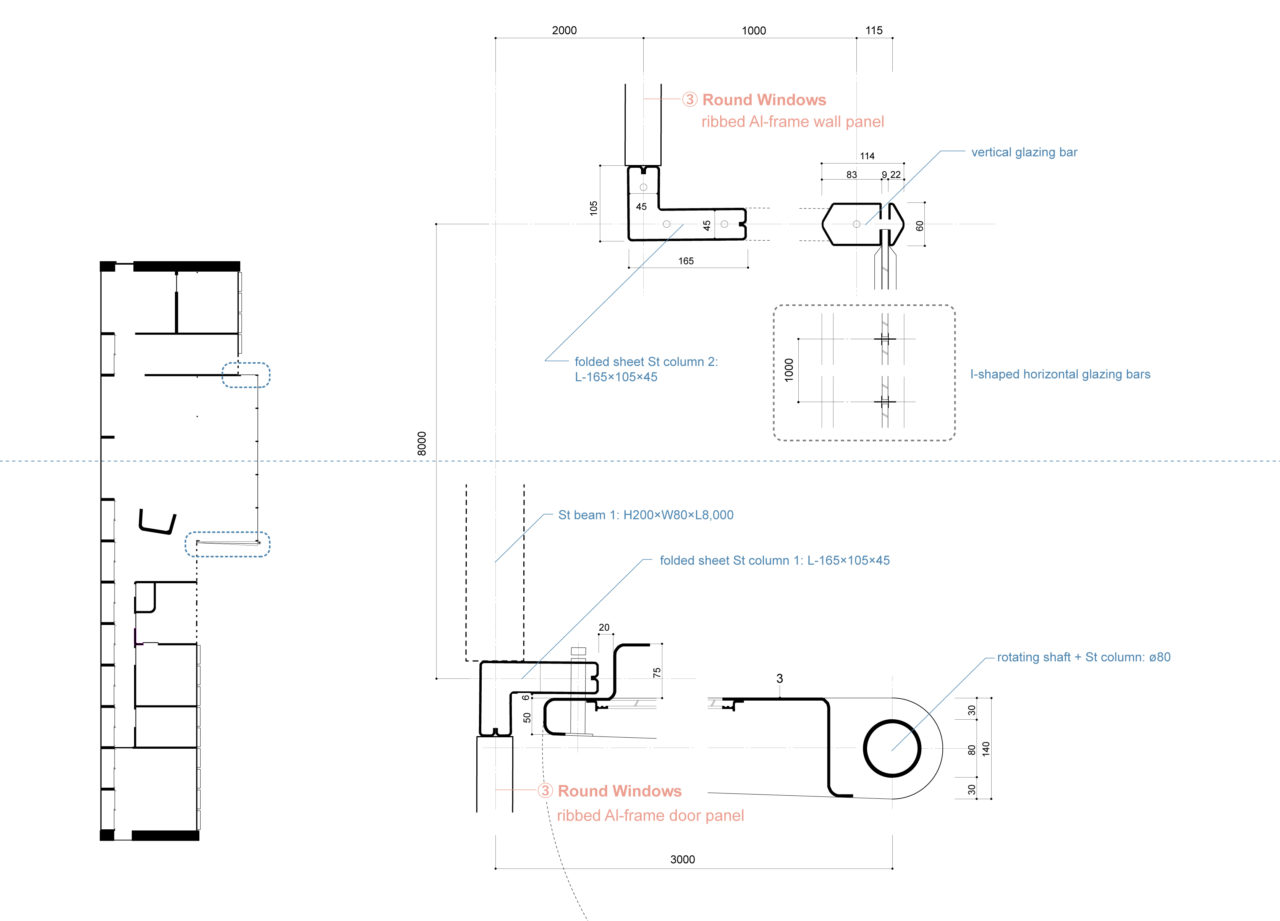

Window #3: Round Windows

These are Prouvé’s most famous windows. Similar windows frequently reappear in his later projects, but if compared closely, there are slight differences. These round openings are set in ribbed aluminum wall panels, which, like the Standard Chairs, were single production components that Prouvé continually modified. The panels are made with finely corrugated aluminum dimensioned to a standard width of one meter, and the 190-millimeter-diameter openings are spaced evenly every 280 millimeters. Designed with functionality as the priority, the panels installed along the wet spaces only have openings above a height of 1.1 meters from their bottom edges to clear the bathtub and kitchen counter, and they are also equipped with operable vents.

The other round windows are located in the ribbed aluminum panels used to make the double door at the entrance. Here, the openings have been designed to extend down to a height of 500 millimeters to maximize openness. The most dramatic sequence in the house occurs here as one exits through the door. When opened, the doorway is transformed into a large rectangular window, offering a full view of the outdoor scenery that could only be glimpsed through the portholes.

Window #4: Vertical Sliding Windows

Vertical sliding windows are used in the study, children’s room, master bedroom, guest room, and part of the kitchen. The one-meter-wide components are made from steel wall panels that are equipped with shutters and finished on the inside and outside with wood. They also incorporate the same mechanism that allows the shutters and sashes at the Building at Square Mozart to be operated smoothly. These panels were originally produced to build post-war emergency homes, and the wood finish was a design solution to enable the panels to be adapted to other projects. One meter was the basic measurement of Prouvé’s modules, and the children’s room that measures two meters by three meters is an especially minimally and efficiently designed space in which the bed, small bookshelf, study desk, and armchair can be laid out in a variety of ways.

-

South elevation

Window #5: Living Room Window

The living room, or the “auberge” as Prouvé called it, is equipped with a fireplace. Occupying the space diagonally across from it as though it were the master of the house was a palm plant, which grew directly out of the ground. The room’s 2.8-meter-tall by eight-meter-long glass curtain wall is one of the largest windows in the house, and it has been meticulously cleared of any structural elements that might obstruct the view to the outside. It is designed with minimal joints between the glass panes, vertical glazing bars made of folded 2.3-millimeter sheet steel set at intervals of 1.6 meters, and horizontal glazing bars arranged to divide the single eight-millimeter-thick panes symmetrically along the centerline between the floor and ceiling. Spanning the length of the living room, the window leads one’s eyes unconsciously outside towards the sweeping view of the city while the plant in the immediate foreground gives one the feeling of being inside the forest.

-

Jean Prouvé ©︎ ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2021 E4396

Photo ©︎ Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Fonds Prouvé / distributed by AMF

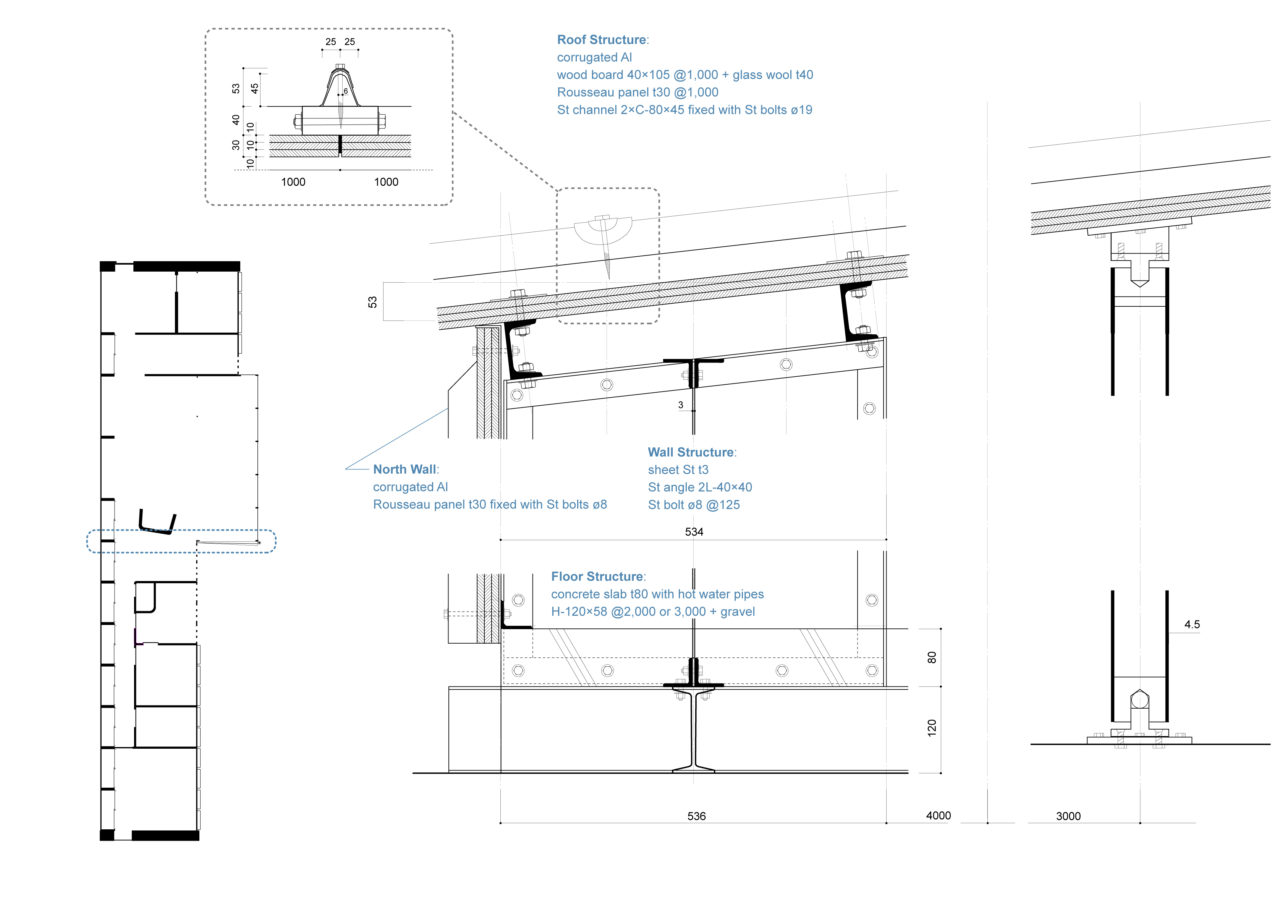

The Structures that Coexist with Prouvé’s Windows

It may appear as though there is a structural wall retaining the lateral earth pressure along the north side of the house, but this is not actually the case. The wall is actually composed of a series of frame units that bear part of the roof load and the wind loads on the long side of the plan but are not subjected to any lateral earth pressure. These units, which are L-shaped in profile and self-supporting, serve as the main frames of the house. Each is composed of a column element made of three-millimeter-thick sheet steel fixed together with steel angles on all sides and a 125×58 I-beam floor joist, and they were arranged across the site at two- and three-meter intervals after the sloping topography was partially leveled along its contours. Considering the fact that the gaps between the columns are used as storage made up of cupboards and closets with sliding doors, one would think that the main frames would also have been effective in bearing wind loads on the short side of the building if they were linked together with steel plates in the same manner as the bookshelves. Prouvé, however, went with the solution of setting 500-millimeter-thick masonry walls at the east and west ends of the house as shear walls that act out of plane. In contrast to the open front façade, the masonry walls create closed side façades and coexist with the steel framed fixed window (window #1) on the inside.

-

Main frame details

The steel roof beam in the upper part of the living room is a reused floor girder from the Tropical House (1949) that Prouvé designed earlier. The beam is bisected by the wall between the living room and kitchen, and it is supported by a total of four round steel columns. With a diameter of only 50 millimeters, the freestanding column visible in the middle of the living room and the two columns positioned beside walls blend well into the spaces as their proportions are similar to that of the structural members of the furniture. The other column by the entrance is designed as a 165×105×45 L-angle formed by welding together two three-millimeter-thick folded sheet steel parts. Its L-shaped cross section gives it a second function as a doorstop for the rotating steel door (window #2), which was assembled using the same method. Even this fragmental instance of the same kind of prefabricated sheet steel components seen throughout the Standard Chair and Maison du Peuple of Clichy incorporates one of Prouvé’s characteristic design ideas for layering multiple functions in a single component. The column also has a rational form that solves two inside corner details at once, as its 45-millimeter-wide face is dimensioned based on the thickness of the ribbed aluminum door panel (window #3) that attaches to it. There is also another L-shaped column behind the palm plant that at first glance looks like a separate component that has been mirrored in plan. However, it is actually just the same component of a different length that has been flipped vertically. The ribbed aluminum wall panel (window #3) of the kitchen that connects to it was put where it is not so much for functionality but out of a desire to establish a common set of details through the repetition of the same L-shaped column.

-

Glass curtain wall and steel rotating door details

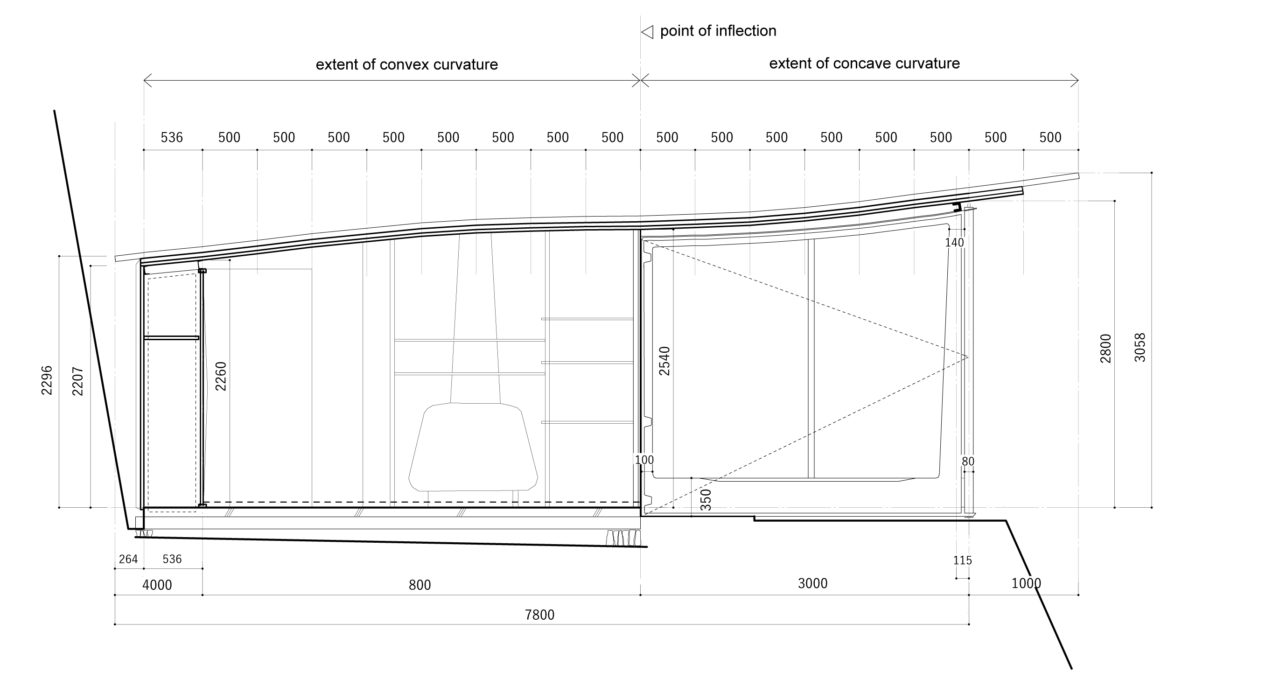

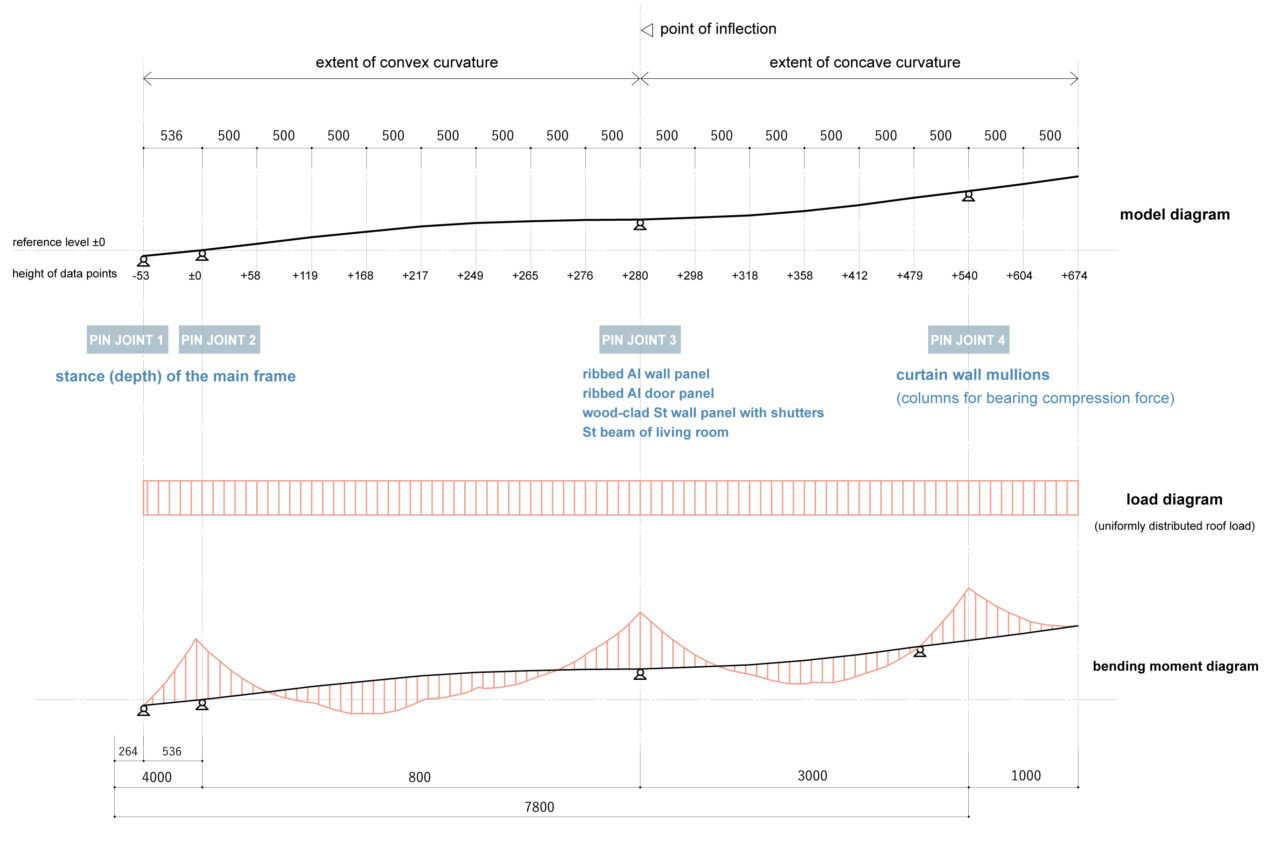

The roof achieves a maximum span of 7.5 meters with a depth of only 30 millimeters through the use of one-meter-wide standardized long-span pressure-laminated wood panels known as Rousseau panels. The roof is slightly curved across the 4.5-meter-span from the north end of the main structural frames to the ribbed aluminum wall panels, the ribbed aluminum door panels (window #3), and the wood-clad steel wall panels with shutters (window #4), which all act as columns. At the edge, where the roof naturally sags under its own weight, the roof is curved upwards to resist gravity and propped up by the vertical glazing bars of the glass curtain wall (window #5). In other words, these bars are designed to serve not only as mullions for the curtain wall but also as columns that bear the compression forces, and they do so with a width of just 60 millimeters despite being 2.8 meters long.

-

Section

What makes this possible are the horizontal glazing bars with I-shaped cross sections, which are arranged at one-meter intervals and prevent the columns from buckling. It should also be noted that the parts of the roof that extend out from the columns (vertical glazing bars) induce a bending moment in the same way as the main frames, which act as fixed joints due to their depth. In other words, this structural system that incorporates downward and upward curvature is composed of coupled fixed-end beams made only of pin joints, and it is an intriguing design that is freed from self-weight sagging due to the symmetrical bending moments that occur around the point of inflection.

-

Bending moment diagram

One could say that the building components that Prouvé designed purely from a tectonic point of view blur the distinction between structure and non-structure and free his work from even gravity and other external stresses that must be taken into account in order to make a building stand on its own. At the same time, the views from the five windows that he created using these components are clearly distinguished as external spaces that correspond to the internal spaces. The Prouvé House still stands today about 50 meters up a steep hill beyond a gate off of a busy main street in Nancy. In 1987, three years after Prouvé’s passing on March 23, 1984, the house was designated as a historic monument and purchased by the city.

Notes

1 . Fondation Le Corbusier, The Modulor and Modulor 2 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2015), 111.

2 . Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 4th ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 302.

Bibliography

A.D.A. EDITA Tokyo. “Epokku mēkingu”. In GA Houses, 21. Tokyo: A.D.A. EDITA Tokyo, 1987.

Fondation Le Corbusier. The Modulor and Modulor 2. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2015.

Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. UK: Thames & Hudson; 4th edition, 2007.

Hayama, Reiko. Kōchiku no hito: Jan Purūve. Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 2020.

Le Corbusier. Modulor 2. Translated by Takamasa Yoshizaka. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 1976.

Reichlin, Bruno, et. al. Jean Prouvé: The Poetics of Technical Objects. Tokyo: TOTO Publishing, 2004.

Sayama, Yasuhiko, Jun Ishida, and Tatsuo Iwaoka. “Study on Jean Prouve, Part 10: Houes in Nancy”. In Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan, F-2, History and Theory of Architecture. Tokyo: Architectural Institute of Japan, 2003.

Yamana, Yoshiyuki. “Jan Purūve no kōjōsei/kumitate jūtaku ni okeru jikkenteki kokoromi”. In 10+1, 41. Tokyo: LIXIL Publishing, 2005.

Reference Materials

Design documents in the Archives Jean Prouvé: Archives Départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle (archival number: 230J648, 29 documents).

Shin Yokoo

Structural engineer, born 1975

Founded Ouvi in 2004 after completing a masterʼs degree in architecture at the Tokai University Graduate School of Engineering and working at the Masahiro Ikeda Architecture Studio. Earned a PhD (Engineering) from the Tokyo University of Science Graduate School of Science and Technology in 2016. Special lecturer at the University of Belgrade from 2017 to 2019 (one-year trainee of the Agency for Cultural Affairsʼ overseas study program). Visiting senior fellow at the National University of Singapore since 2020. Notable works include the House in Nakago (2021; collaboration with Snark), 4 Episodes (2014; Atelier Nishikata), and Jukkaie (2009; collaboration with Point). Notable research includes “Design Feature of ʻMaison du Peuple de Clichyʼ Designed by E. Beaudouin, M. Lods, J. Prouvé”, (AIJ Journal of Technology and Design, Jun. 2015), “Study on the Relationship Between Features and Building Components of ʻAéro-Club Roland-Garros à Bucʼ” (AIJ Journal of Architecture and Planning, Jun. 2015), and “Study on the Relationship between Features and Building Components of ʻMaison démontable en ancier BLPSʼ” (AIJ Journal of Architecture and Planning, Sep. 2017), among others.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Jean Prouvé’s Windows

The Windows of the Cachat Buvette in Evian|Jean Prouvé’s Windows #4

18 Jul 2024

Jean Prouvé’s Windows

Windows of the Villejuif Temporary School|Jean Prouvé’s Windows #3

28 Mar 2024

Jean Prouvé’s Windows

Four Tectonic Features that Reside Within Prouvé’s Window Details

04 Aug 2021