Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Breathing in the Desert:

Yazd, Iran

01 Oct 2019

The bus that headed from northern to southern Iran passed once more through alien landscapes created by the desert. It’s as if one must pass through other planets before arriving in another city in Iran.

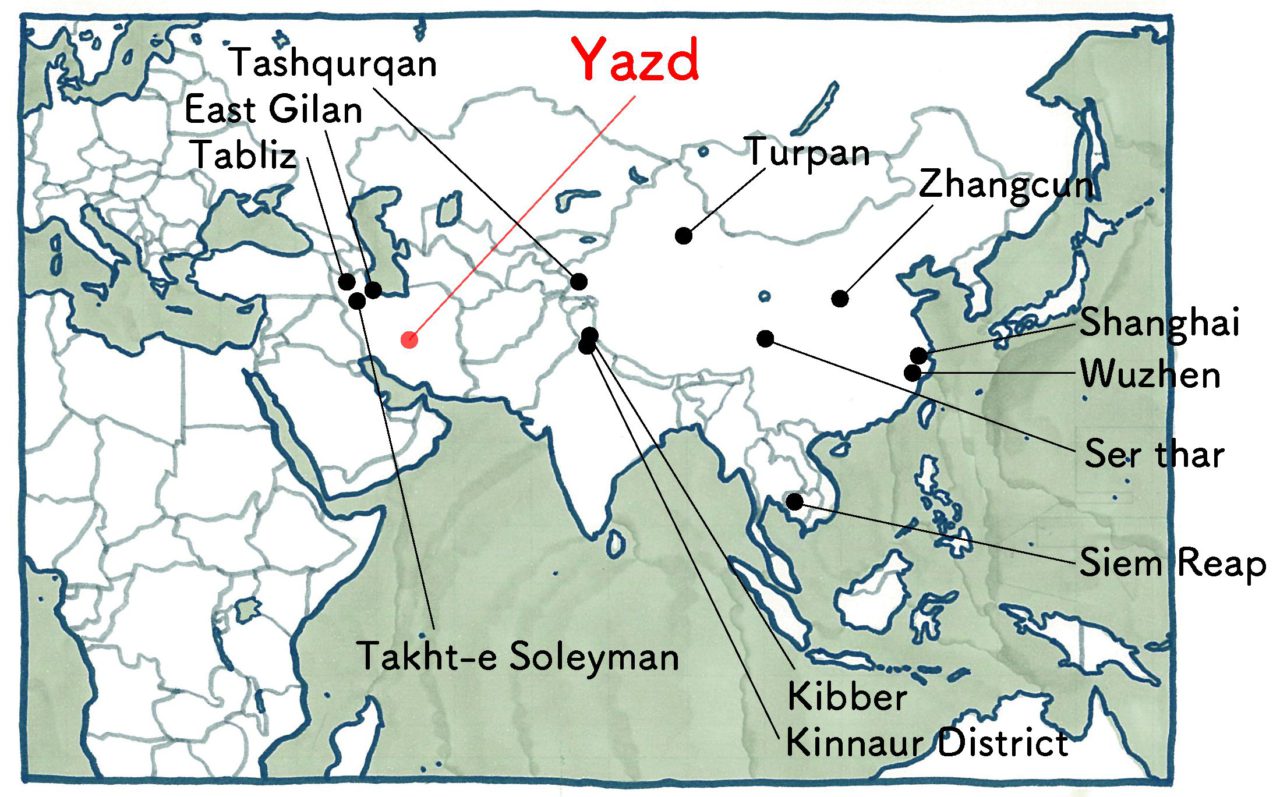

Speaking of which, as I planned this trip, I showed an acquaintance a world map with places of interest marked down, only to have it pointed out to me that it was all desert. I hadn’t realized it until then, but there does indeed seem to be something fascinating about deserts to those born in countries without them.

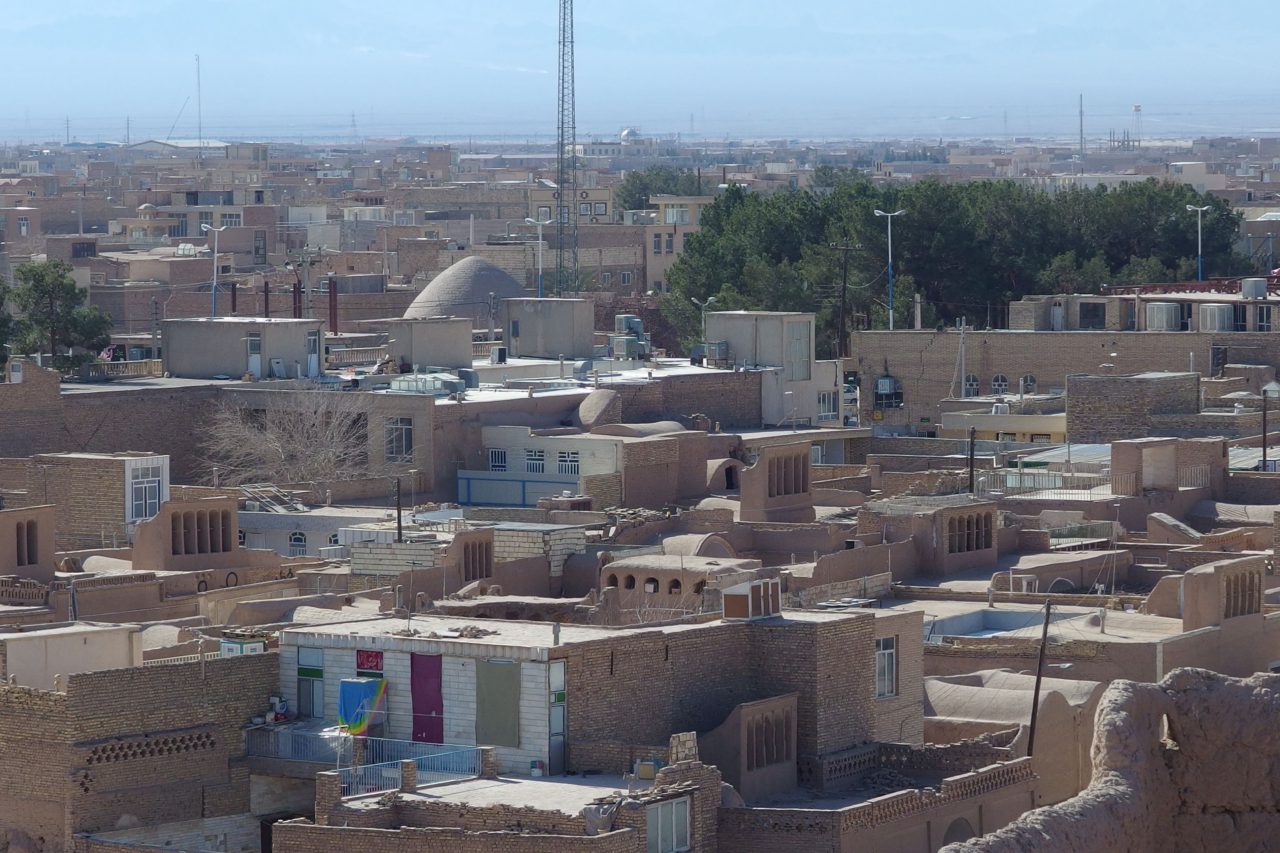

The desert oasis I now visited, Yazd, is a city that also maintains that kind of a fascination. Though you can now find modern structures there, in the past, the difference between architecture and landscape in the city must have been whether or not the sand in a given location had been hardened.

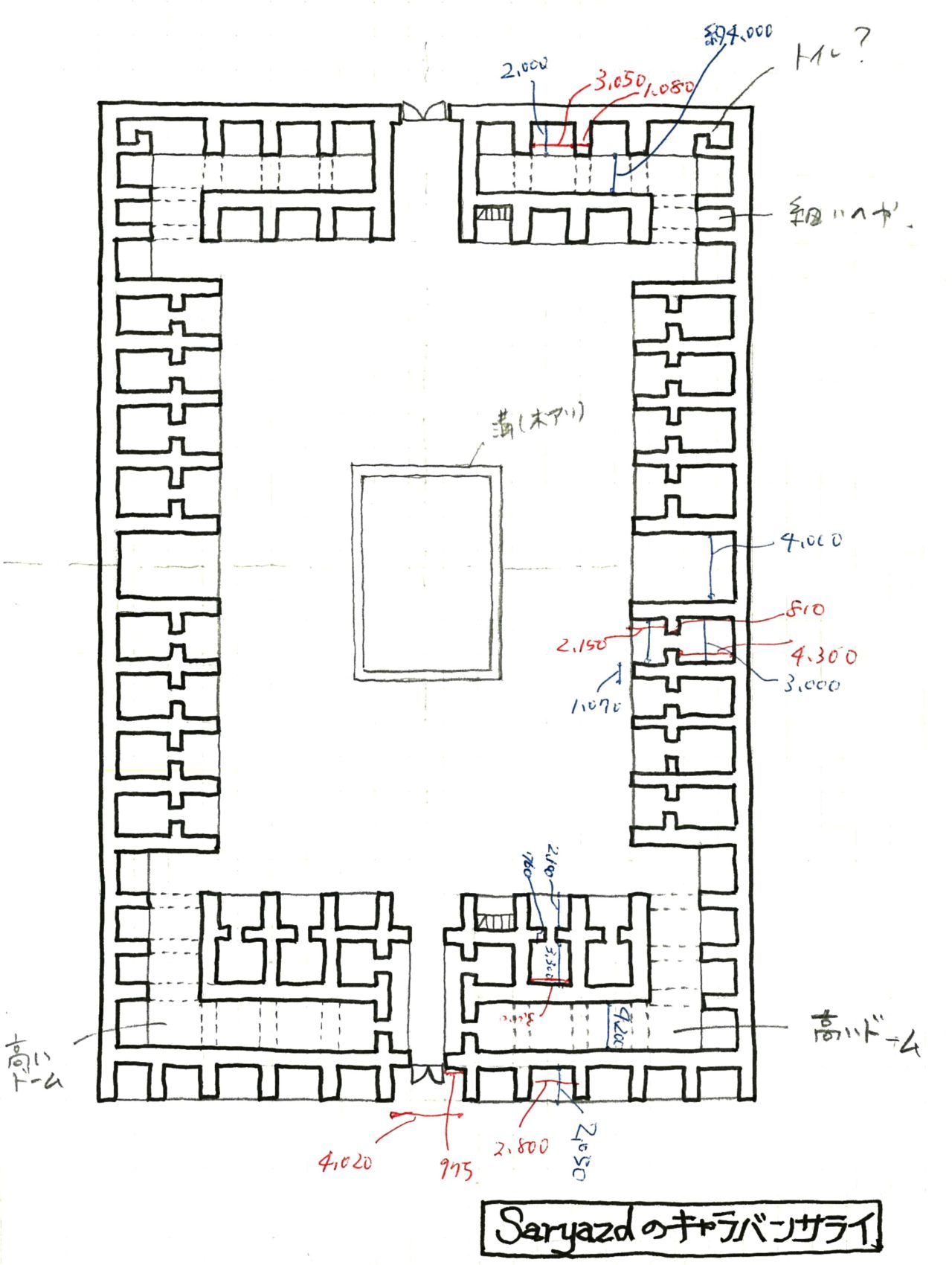

As I walked, I noticed a number of men mending a caravanserai. It had been used since the 11th-12th century as an inn for merchants, and their intention now seemed to be to fix it so that it could be used as a tourist facility. A man there who seemed to oversee the site came to speak to me. He wore a red polo shirt, and he offered to show me around the area.

-

he courtyard of the repaired caravanserai

The bedrooms once used by desert caravans face a courtyard surrounded by sun-dried brick walls. Lined in regular intervals, each room contains a pointed arch. You could say that here, enclosed areas were built in order to protect oneself from the sand, followed by the creation of a courtyard that acts as a large window facing the sky. From there, secondary windows facing it were constructed for each room.

Four arches slightly larger than the ones used for the rooms are located facing the center of each of the courtyard’s sides. These are also characteristic of a type of Persian-style mosques known as “4-iwan mosques,” which take after the arched spaces with open facades from the Sasanian Empire known as iwans. Their shape is a strong display that the focus of this architecture is on what is inside.

The structures here seemed closed off, and their facades can only be described as cold. It wasn’t as though the people here lived in dark, stagnant caves, of course. There had to be holes somewhere to allow their homes to breathe. The most typical form this takes is the courtyard. The idea of “surrounding” that I learned about during the previous issue in wastelands of Takht-e Soleymān seemed just as essential in this desert as well.

-

Floor plan of the caravanserai

The overseer in the red shirt left the courtyard, then showed me the underground cistern next. Though the city may be a desert oasis, it is still artificially created. Underground water channels like the karez I saw in Turpan, China known as qanats had been used here in Iran from an even earlier time.

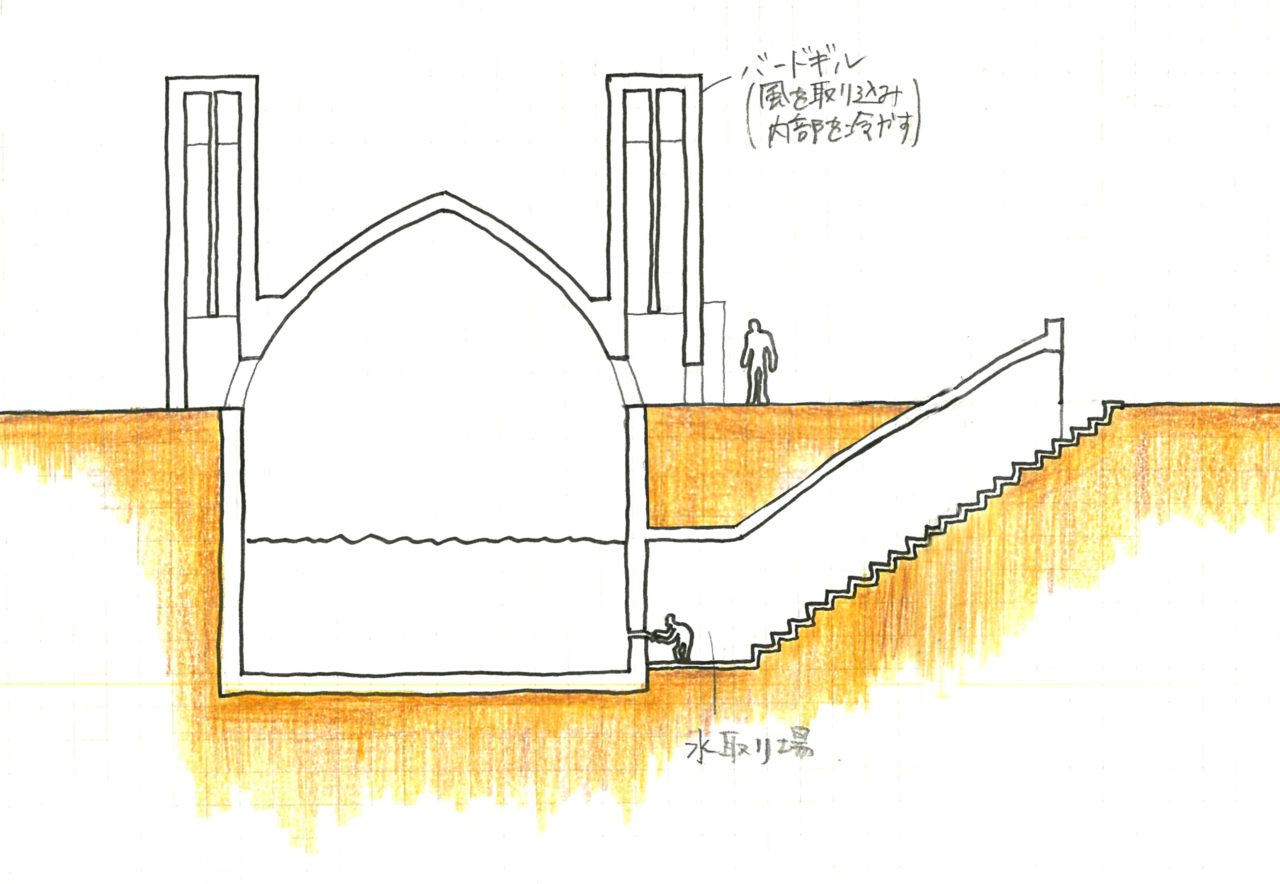

This cistern that drew water from a nearby qanat is known as an ab anbar, and two towers stood to the side of the building’s tipped dome. These towers are known as badgirs, and they catch the wind from their upper openings in order to chill the water. Placing these openings high above the ground must allow them to prevent sand contamination while also making use of the stack effect to circulate air.

-

The cistern (ab anbar)

In order to draw water from this cistern, one must enter from a somewhat distant spot and descend underground from there by stairs. Whether badgirs or entrances, I could tell that openings must be created either high above ground or under it, and that openings near ground level were avoided at all costs.

-

Cross-section of a cistern (ab anbar)

-

The inside of the badgir

Looking up into a badgir from below allowed me to see the tower had been divided into cross-shaped sections. It’s made in such a way that the wind is taken in using holes on one side and led downward along the inner walls.

The cityscape of Yazd is made up of these badgirs, their designs diverse and varied. In Meybod, a town in the outskirts of Yazd, the north-facing badgirs let one know the direction the wind comes from.

In this place, the buildings are enclosed to protect people from the harsh land, dig under the ground (underground water channels, cisterns), face up to the sky (courtyards), and contain holes in even higher locations (badgirs). Yazd is filled with inventions that allow one to breathe in the desert.

-

Groups of badgirs that all face the same direction (Meybod)

I found homes with skylights bored into their centers not only in Takht-e Soleymān or Turpan, but also in homes belonging to Tajiks (an Iranian ethnic group) in Tashqurqan, China. Important ceremonies such as celebrations were carried out in these areas. We may be able to say that courtyards from older times changed form into these skylights as a way of adopting to the climate.

When you think about it this way, such wisdom regarding methods of breathing in the desert may have changed into more forms than we can imagine and spread itself across the world.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.