Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Memories of a Skylight: Tashqurqan, Part 1

31 May 2017

I headed further west from Turpan by train to arrive at a city in the western reaches of China called Kashgar. From there, I climbed a mountain for 7 hours aboard a bus that kicked up sand and dust all the way as it climbed. The true western edge of China lies at a point around 3,100 meters above sea level, in a town called Tashqurqan that is partially populated by Tajiks. They are Muslims that speak a unique dialect of Tajiki and are related to Iranians, though they are different from Uyghurs.

Yet further west of Tashqurqan, the vast as of yet unknown to me regions of central Asia sprawl out, made up of countries like Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. These were the Pamir Mountains, a place known as “the ceiling of the world.” I am told that as the most western settlement in China, Tashqurqan has a long history as a point along the Silk Road. There, they use Beijing time and the sun does not begin to set until 11:00 PM, as if to remind me just how man-made the concept of time is.

Like Turpan, there were roads in the center of the city, and people of Chinese heritage lived there. I asked the staff at my lodging how I might find a Tajik house to observe, and was told how to get to the area in which they live. It was a bit of a distance away. I set out straight away, and the asphalt roads soon gave way to dirt ones. I walked for 20 minutes, hearing fewer and fewer voices along the way, until at last a beautiful landscape appeared before me.

-

A vast field of rape blossoms

Before the mountains and blue sky was a field of rape blossoms like a recently laid out carpet. Perhaps that is what heaven is like. I walked alone inside the quiet scene. Gradually the Tajik houses came into view. Square, earth-colored houses were scattered randomly about the middle of the farmlands. The river that flows down from the Pamir Mountains must keep the village alive. Crops grew there, in those lowlands.

The picture was taken looking down from atop a small, steep, mostly bald hill, which was being used as a graveyard. Because not much rain falls there, the houses had flat roofs, and there were trees planted about them that functioned as windbreakers.

-

The Tajik village looking down from the small, steep hill

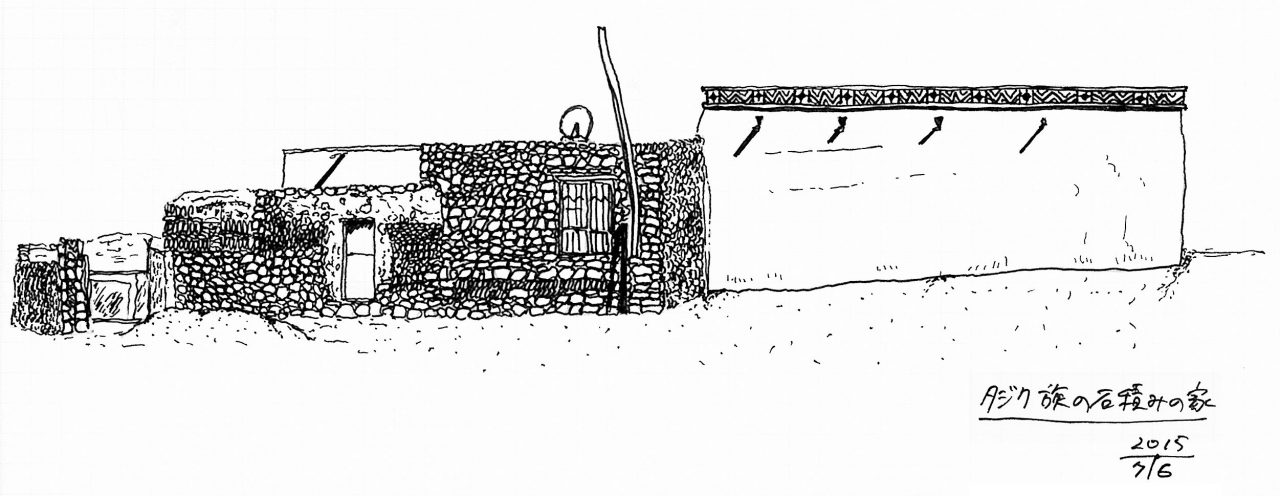

I found a house along the river. I took my time observing it, since no one was there. It was apparently made mostly of stone, with some brick, and on the top of the walls, which were covered in mud, was a red cloth upon which some unique image was drawn in black. This image could be found on all the nearby houses. The stones appeared to be round ones taken from the river.

-

A sketch of the Tajik house near the river. The area sticking out to the side made of stone had no roof, and was used for livestock.

As I stood zoning out beside the river, a boy and middle aged man were doing farm work. The middle aged man dressed classy (I’ll call him “Classy” from here on), and he approached and started saying something to me.

-

The Tajiks I met along the river

I looked on as Classy spoke to me in Chinese. I didn’t understand what he was saying so I showed him my sketch, and in moments we were on our way to his house.

-

Classy’s house

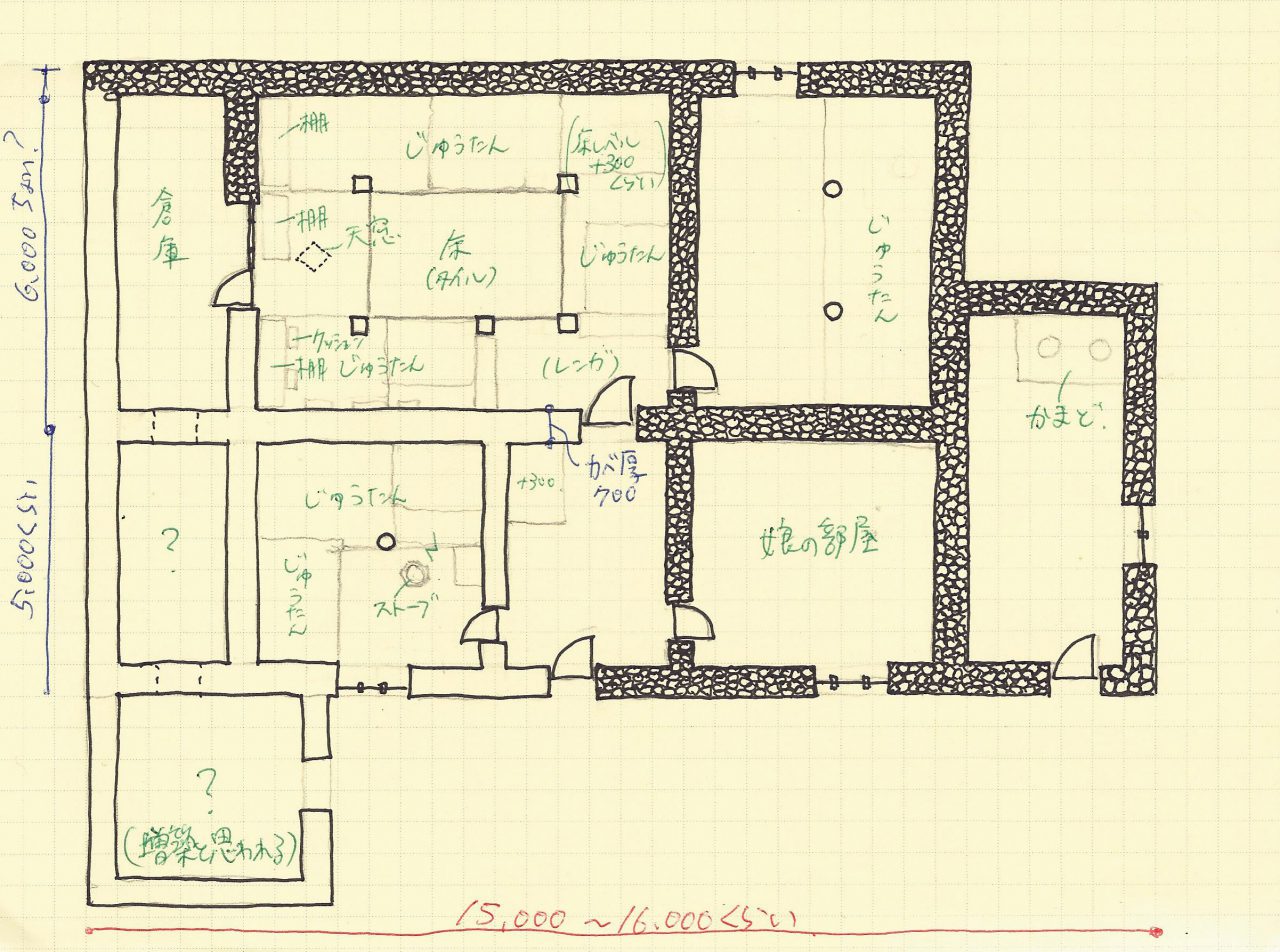

His place was also partially stone, partially sun dried brick, and the top of the mud covered walls was decorated with the same image. He gave me a tour of the place, which was nice and may have been built relatively recently.

-

A blueprint of Classy’s house. (The walls are mostly stone.)

The walls were 700 millimeters thick, which indicated how cold the region was. I was led into what appeared to be a living room, the largest room, in the top left of the middle section of the blueprint. Over half the room was like a bench, and there were rugs covering the floor, with cushions lined up neatly. There were also many decorations. The family must gather there and pass the harsh winters.

I sat there and was treated to some pulled noodles (laghman noodles) his daughter made. The noodles were similar to udon with tomato sauce and vegetables atop them, and were very delicious.

-

The laghman noodles they treated me to. They were delicious.

Classy lit a cigarette and watched silently as I ate the noodles. There were no windows in the room. The only light came pouring through a skylight. I understood that this place, that appeared as if it were an altar, was the most important place in the house, as I stared at the tobacco smoke drifting upward through the light.

-

The space below the skylight

After I finished eating, Classy took me out in his car. It seemed he had something he wanted to show me.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.