Series Traveling Asia through a Window

"Placing" a Home: East Gilan, Iran (Part 1)

14 Dec 2018

Iran was an unknown land to me before I visited it myself. My vague image of it had been of a desolate desert dotted with ancient remains. And so I was surprised to learn that Iran, like Japan, had areas with a temperate climate where rice could be grown. One such area was the one I visited here, the northern province of Gilan, located along the Caspian Sea.

I visited this area because I heard of people “placing” homes there, but all I knew in advance was that these strange houses were located in the province. I wasn’t even sure of which exact villages to visit. To find out, I decided to first visit a museum of history located in Gilan’s capital, Rasht. As always, my journey was an improvisational one.

I was stunned when I saw a home that had been relocated to the museum. This two-story home topped with a thatched roof had been “placed” on top of a platform of piled-up earth. I had never seen a house built in this way before.

-

The museum’s relocated home

What was oddest of all was the home’s foundation, alternating sets of wood placed on top of each other in a 5×2 line arrangement. Why had such a strange construction method been used here? A female researcher told me that this was done to protect against the frequent earthquakes experienced in the region. Tremors could be absorbed through the use of alternating layers of timber (which have profiles in the shape of broadening trapezoids), so by “placing” the floor of a home on top, one could create a seismically isolated structure that was not fixed to the ground. In fact, during the large 7.4 magnitude earthquake in the northern part of Iran in 1990, “no damage” had apparently been suffered by this “placed” home.

-

The home’s strangely constructed foundation. It is placed on earth, rather than buried in it.

When I entered inside, I found a log house-like room that was surrounded by criss-crossing lumber walls. Its walls were thick and plastered over in earth. This could be the result of Iran being colder than I had imagined (snow was still on the ground during my January visit), combined with its wealth of lumber due to its temperate climate. Another possible interpretation seemed to be that a heavier superstructure would help stabilize the home due to its “placement” on top of the foundation. Perhaps it was difficult to create openings in such a log house-like structure, as there were no windows other than by its entrance.

On the other hand, its hanging terrace was built to be extremely large. Windows had not been used to make the inside of the rooms more pleasant, as the rooms were only built to be as small as possible. In exchange, a resolute decision had been made to secure as much space as possible for the terrace, which sunlight streamed into. This philosophy was somewhat similar to the dwellings in the “Overhanging Village” I visited in India.

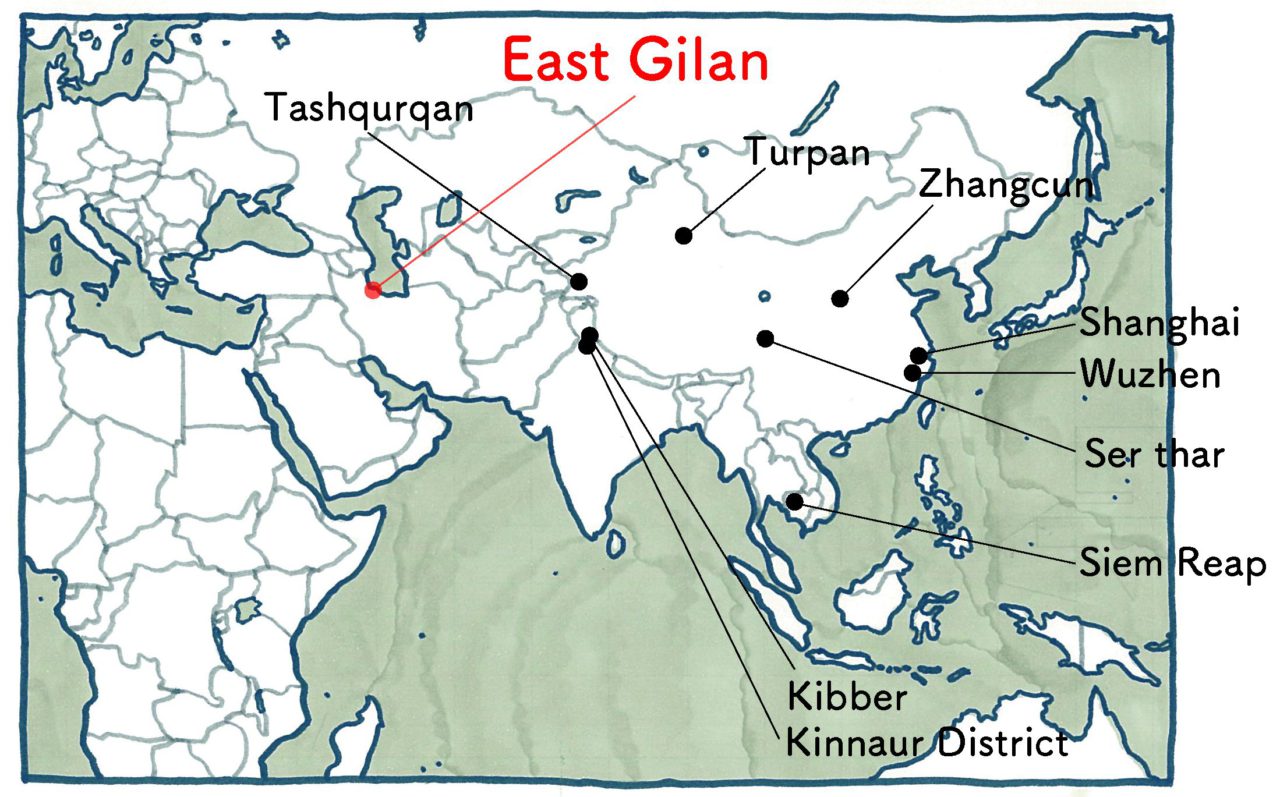

The fact there were nearly two meters between the ground and the base of the first-floor terrace was also apparently a flood precaution measure. In fact, one can see homes like this one spread around the region to the east of the large river (the Sefid-Rud river) in East Gilan. I tried to imagine the upper sections of these homes floating and bobbing in the water, but I doubt that in reality they would float, given the thickness of their walls.

As there were barely any visitors other than myself when I visited the museum, the researcher gave me these kinds of rigorous descriptions as we walked about. I learned that many people now live in new homes made of concrete, and that traditional homes are being used as storehouses. Even now, a traditional home such as this one is surely being used as a storehouse somewhere. Despite this situation, though, I was also able to learn that such homes were still being inhabited by people in the nearby village of Seda Poshte.

The next day, I used my struggling internet connection to locate my destination, then headed straight for the village. I discovered a home in active use just a few minutes after I entered the town.

-

A home still being used to this day. Fabric covers the terrace.

While this is a small-scale, one-story home, below its floors was another splendid example of the kind of raised, seismically isolated foundation I saw in the museum. Its roof was made of metal, not thatched grass, and its terrace was surrounded by fabric to create a more private, semi-outdoor space.

Not long after, I found a fairly massive two-story, one-family home. As terraces had been added to it on both its left and right sides, it had double metal roofs. Still, its roof was massive. But as I suspected, its interior spaces were kept small after all. While the house did have windows, the vast majority of it was made up of heavy walls.

-

A two-story house. Terraces have been added on both sides.

The head of the household allowed me to enter into the terrace area of his home. The front terrace was over two meters in width, and carpets had been laid down on its floor.

-

The front terrace area

-

The added terrace areas

The added terraces were large enough that you could even consider opening a modest café in them. Together with the sunlight they received, they seemed extremely comfortable. I could tell that the space was used as a living room and kitchen by the sink in the back.

As many Japanese residences are built using timber frames, their many openings make it easy to create windows. As someone who had been raised in such environments, these bold spaces born from circumstances that make the creation of windows difficult seemed to turn what I held as common sense onto its head.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.