27 May 2016

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Conversations

- Interviews

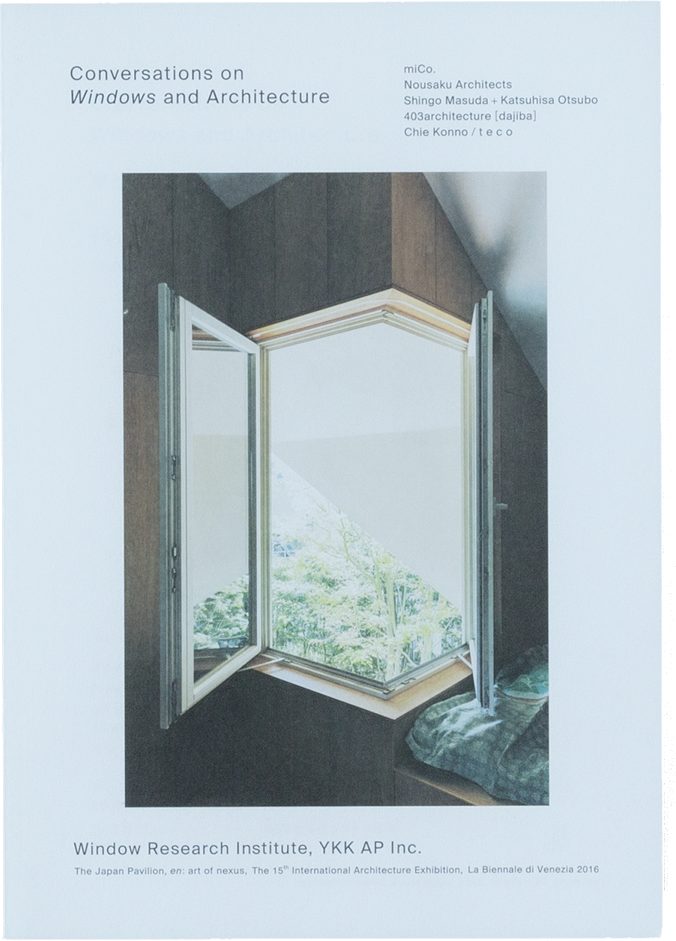

“En: art of nexus” is the theme of the Japan Pavilion at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016, one of the world’s largest modern architecture festivals. How are the exhibiting architects interpreting the theme? What are their ideas of the various forms of “windows” in architecture? The venue designer, Chie Konno interviewed the architect, Shingo Masuda by taking actual works as examples.

Chie Konno (hereinafter referred to as Konno): Would you please give us a brief introduction of yourself?

Shingo Masuda (hereinafter referred to as Masuda): It is now in the 9th year since I graduated from university and started to design with Katsuhisa Otsubo. The client of this “Boundary Window” (2014) was looking for a young architect to work with, and we had an offer after the client saw competitions for young Japanese architects such as SD Review. The building has somewhat unique uses: a program for a weekend house that is rented out as a photo studio on weekdays. Since the interior decoration of this building would be continuously renewed to follow trends, we figured that we could not design that part. However, the client placed much value on natural lighting, and window designing was left to us.

-

“Boundary Window” ©Shingo Masuda + Katsuhisa Otsubo

Konno: It was such a strong debut that you and Mr. Otsubo made at SD Review. It was so impressive that I can easily understand many clients want to share such a beautiful world view with you.

I never knew until this visit that this building is used as a photo studio. Now, I have experienced this space for a little while. Such use is perhaps one of the reasons why the largeness of the façade and its brightness can be wholly experienced in a room having only a few objects. By the way, which direction is this façade facing?

Masuda: The window was added to the façade, facing the garden in the south. The site is arranged in a common way, with the garden in the south and the building in the north. The client wanted to have the garden full of green, and to make a relationship between the garden and the inside of the house more freely. However, considering the typical arrangement plan of this site, most of the garden gets shadowed in winter by the wall or the house in the front facing the south. Therefore, we thought of having window glasses higher than the building itself so that the light on the window would be reflected to the garden, making it brighter.

Konno: That is true. A southern-side arrangement plan is a common solution in the northern hemisphere, and it maximizes a continuous garden area. However, shadows are unavoidable. I felt it was very interesting to develop the design, not only considering the value of maximizing the garden area, but also its quality. What was the client’s response to your first presentation?

Masuda: Our presentation is usually like a survey. When we first gave a presentation to probe the client’s desires, the client seemed to have a little bit different idea. Then, we presented this scheme the following month and the client agreed.

Konno: You said it so easily, but it is a kind of idea that most of us would never even think of. Could you explain the process of reaching this idea?

Masuda: In the office, we actually discuss very general and common things. For example, when the client wants to have it brighter, or to keep it as open as possible, what we think of is “hey, the sash is a cumber.” Even though the window is open, it’s in fact only half open because the sash and the curtain rail are still there. It’s not really open, is it? Then it may be an option to have a detailed design for “keep it as open as possible”, but the circumstance would not be changed so much from a larger point of view. In addition, the handrail is still there. In that case, what about treating the handrail as something important in the first place? Moreover, we always keep the relationship of scale in mind when we design. For example, an opening which is decided by internal logic is too small and too lived-in feel to go along with the external scale, that is, an experience in such an open and generous garden. On the other hand, laying out large windows would in turn make an experience inside the house unnatural. We, therefore, tried to keep the balance of being small but staying large at the same time. Then we discussed the thickness and weight of glasses, and the steel front of a structural member to support the glasses and its weight.

In addition, the balance between these elements was also important so that a resident can easily and naturally open the windows. Curtains are hanged at the height of rooftop to the ground level, there is no curtain rails around the opening. Sash and the front side are not fitted to the opening, and thus it is somehow open even when the opening is completely closed. Instead of just weakening the border to connect the inside and the outside of the house, we wanted to realize the wholeness of this site by introducing relationships among various things.

Konno: I suppose a sliding window is an attractive style that was invented within the conditions of Japanese wooden buildings, and I like it a lot. People usually accept the characteristics of “half of the window remaining unopen” due to its structure as a precondition. However, you straightforwardly doubt the precondition. I believe that such way of deciding where to draw the start line is a characteristic of Mr. Masuda and Mr. Otsubo. Furthermore, the ability to slide the window is barely left within a human’s reach, but it is diverted from the concept of “common sliding windows operated by humans.” I consider such a sense of balance is truly attractive. Could you explain how you interact with things such as the scale of an existing building and an opening already existed?

Masuda: Most of architecture we have renovated so far are livable enough as they are, and this architecture had no problem to live in, either. So we don’t change the existing part so much, nor are we conscious about it. We don’t even design the size of a window based on the size of an existed opening, since we consider the gap between the architecture and the surrounding can become the design itself. When it comes to the height, we first set the height from the first floor level to the handrail on the second floor, and when it was decided, the height of the bottom part was inverted to the upper part.

Konno: A floor slab alone is quite physically removed from the architecture, and then the window size is defined by designing the handrail that is associated with human activities. In such cases, adjusting relationships, such as the maximum building height and the new façade height in relation to the maximum building height, becomes unnecessary. Is that what you mean?

Masuda: That’s right. It is very dry, but we want to make our choice by gauging a tipping point of circumstances in each phase.

Konno: That’s interesting. I believe architects more or less design from a viewpoint of how to integrate and adjust various factors, with an overall picture in mind. But in this work, the architecture is not the subject of such manipulation. It seems more like an accumulation of parts and materials to be experienced. Have you ever heard of a concept of “Umwelt” by the biologist Jakob von Uexküll? It is said, for example, when explaining a living organism, ticks, the explanation of ticks would be completely different between an objective description of ticks in a world that is perceived by humans, and a subjective description of a world that is perceived by ticks. Ticks see the surrounding world based on butyric acid emanated from mammals, the texture of mammal skins, and temperature. This explains characteristics of ticks well in a different sphere from when humans describe the characteristics. I have a feeling that your thoughts in designing may be similar to this. When you decide to start from a border created by a window, you carefully look into related elements like a handrail and curtain, as well as details of the window including the weight. Conversely, you set aside unrelated elements such as interior decoration and the building height. I have an impression that you are casually doing this, although such dryness requires some courage.

Masuda: I once talked something like this with Otsubo. When you are looking for an apartment, you may choose where to live based on the location, size, rent, and usability of the room. But sometimes, we may decide the room by what you can see from the window. That is, it would be more valuable to appraise how the boundary between the inside and outside is affecting the space might be more valuable than the space of the room itself.

Konno: I think such consensus is a feature of you two. In your previous works, you must have been highly conscious about things including borders and the scenery beyond. I wonder if this feature is contributing to eliciting hazy, potential ideas from the clients. By looking at one thing from different angles, the overall value changes. Finding such a transition point and persistently continuing to question it. I wonder if you somewhat believe in a thing ultimately left, like an unchanging value of architecture.

Masuda: Right. Maybe because two of us are working together, but we need to end things dry. It is important to narrow down to one value at the end. Straining to make a new architecture is unfaithful in my mind. Instead, it is more important to pursue in the project an appropriate standpoint as a designer.

Konno: When I saw a photo of the original building before renovation, I was truly shocked. The façade appeared to be a cut-out building with a curtain wall system. Its scale was hard to understand in the trimmed picture. The significant incongruity, or a jump, was felt brilliant to me. Meanwhile, the existing part facing the north side street is more robustly and tightly closed. How do you and Mr. Otsubo perceive the existence of “city”?

Masuda: At least in the case of this house, the client wanted to close the north side, which is facing the noisy street. We made a decision to close the north side as well since we can still bring light into the house from the south. On the south side, the resident has the connection with neighbors via garden. It was very good to keep the garden in a good condition for the surrounding condition. In fact, we often visited the site after completing the construction and had a chat with neighbors in the brighter garden, over the fence.

Konno: If it were a closed site from the street, it might be understandable, but I was surprised today because the site is facing a street. Architectural designs appear to have somewhat social responsibilities to me. I don’t think I can ever make such a decision.

Masuda: Right. We could have designed a border of the street side and the building instead. But the street side is noisy. The surroundings did not seem to have an active relationship through the open windows, for example. The sidewalk is only about 50cm wide. Since the site is right in front of a crosswalk, it was appropriate to remove the fence and make a wide open area of about 2m. Therefore, we could understand the client’s desire to dissociate with the street. It might be misleading but I dare say that the other important thing we are conscious of is to avoid overlapping our standpoint with that of the client. When these standpoints are overlapped, random issues arise, such as agreeing or disagreeing with each other’s sense. We believe that the most important issue is how the client entrusts us in terms of idea proposals beyond the limit of designs. If the client does not entrust us, I think our project will not work out.

Konno: By properly deciding on the scope of work, you improve the performance and quality of the work. Architects often tend to keep integration and creation of an overall picture in mind. However, I suppose you two are good at designing within a scope where your specialty is fully exerted. There are more renovation projects for our generation. If such judgements can’t be made, spaces would be homogenized, and it’s like, I can’t dream in architecture.

In addition, in terms of how much potential in general residential areas can be extracted, such as the south arrangement, it has a kind of universality. It’s like being independent as a particular solution, affecting a wide range.

Masuda: In our previous work “Living Pool” (2014), we explored baseboards and foundations. Even though the baseboards are rational and functional, architects move on to eliminate them. That’d be because the baseboards are taken as a miscellaneous taste in the wholeness of a space. But they should simply be considered from the first point. A foundation is not a factor to add later, instead, as the term “foundation” suggests, isn’t it important with various implications? The conventional method to think of overall architecture from a higher perspective is surely important. However, I’d also like to have another micro perspective to capture the whole. That is, looking carefully at the factors and parts in the course of a trial and error design process, while buried in desperation and reality.

Konno: It is simpler if the baseboards are removed and the border of the floor and wall abstractly meet, but you accepted the meaningful factor of the baseboards, and at the same time, you made it a key element of expression.

Masuda: Correct. As soon as I see myself trying to remove the baseboards in order to make things stylish, I feel bereft.

Konno: The characteristics of your works appear to be an approach for intricate and specific things. But actually, an objective approach is creating a balance, isn’t it? Before meeting you, I took a look at the presentation drawings, and I thought you are trying to create minimal and stylish spaces.

Masuda: No, it’s the opposite. It’s usually “this is the only spot to design.”

Konno: Apart from actual buildings, I believe your exhibition so far is very characteristic of a way of cutting out a subject and its accuracy. Would you please explain your exhibition at the Venice Biennale?

Masuda: We make a section model in 1/5 scale. A 2m*3.5m overall photo at the same scale is also presented. It’s fairly simple. How to present the part we designed in the model is important. The model is partially cross-sectional.

Konno: When I imagined your exhibition at first, I wanted people to experience the beauty and incongruity. As a result, this large screen and the way to present the details are clearly indicating your viewpoint, I consider. The main theme of the exhibition of Japan Pavilion this time is “en“, and if you look up the word in a Japanese dictionary, you can find meanings such as connection, kinship, engawa (verandah), as well as edge or border at the same time. “En” has a very broad concept and the aspect of an “edge” is dryly and architecturally expressed. I’m sure the exhibition will be very crisp and dynamic.

Masuda: What we mean by “en” here is rather abstract, describing the relationship between the garden and the window, and how a person enters and interacts with the space. This window, in particular, is much larger than the human body, so it may be appropriate to say that we interact with the window, rather than we use the window. We hope that having a fifty-fifty relationship with the window, you can feel the “en” with things which you have never felt before.

Shingo Masuda

Born in Tokyo in 1982. Graduated from Musashino Art University and co-established Shingo Masuda + Katsuhisa Otsubo in 2007. Part-time lecturer at Musashino Art University since 2010. 2015 fall Cornell University Baird Visiting Critic. Honored with Gold Prize of JCD Design Award 2011 and 2014, Second Prize of AR+ D Awards for Emerging Architecture 2011, and First Prize in 2014 (UK).

http://salad-net.jp/

Chie Konno

Born in Kanagawa prefecture in 1981. Graduated from Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2005. Studied on a scholarship at Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule while in Graduate School of Tokyo Institute of Technology. Finished Doctor course at Tokyo Institute of Technology with Doctor’s degree in engineering in 2011. Assistant at Graduate School of Kobe Design University in 2011-2012 and established KONNO. Assistant professor of Nippon Institute of Technology since 2013. Established t e c o in 2015.

http://te-co.jp/

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Steel House

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Exhibition “Present State(ment)”

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

House at Komazawa Park

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Sunny Loggia House

27 May 2016