27 May 2016

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

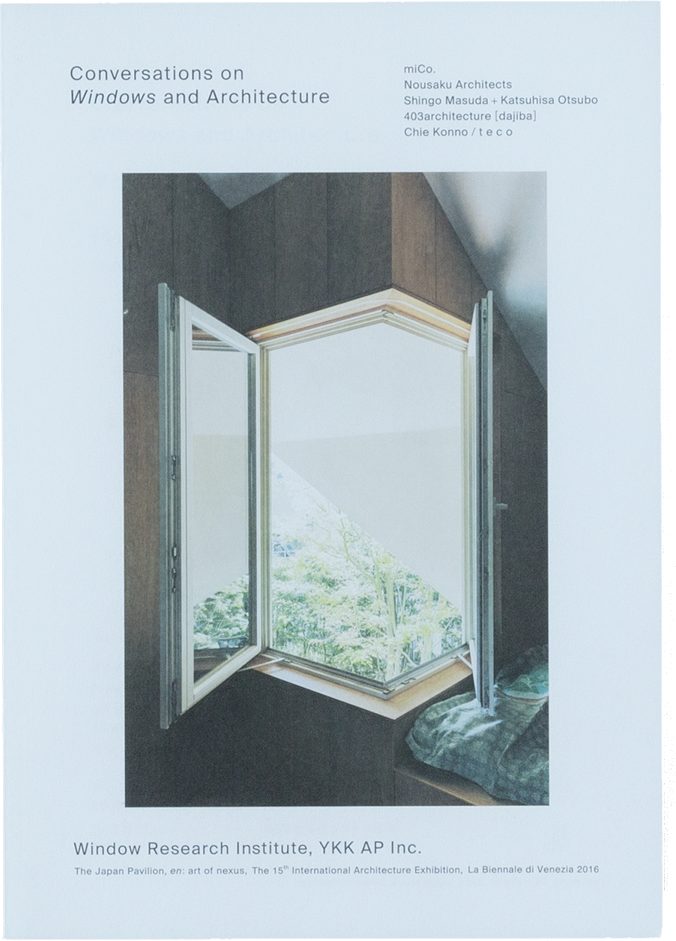

“En: art of nexus” is the theme of the Japan Pavilion at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016, one of the world’s largest modern architecture festivals. How are the exhibiting architects interpreting the theme? What are their ideas of the various forms of “windows” in architecture? We interviewed the architects and the venue designer by taking actual works as examples.

You have designed architecture with distinctive windows such as “Steel House” (2012). What do windows mean to you when you design architecture?

Fuminori Nousaku (hereinafter referred to as Nousaku): What I keep in mind when designing architecture is to provide large open windows towards the city. The “Steel House”, for example, has a large window by joining double sliding aluminum sash windows. When a house closes itself to the city with a wall, it means that there is no connection with the community. Meanwhile, having large and open windows at the front of the house can also cause problems.

For example, if you just provide large windows, there is a problem of privacy and passersby may look in through the windows. It is, therefore, necessary to provide something to block the stares of passersby, such as making level difference or planting a tree. Another problem of large windows is to enlarge the environmental burden, and it requires blocking the strong sunlight in the summer. I try to seek a complex balance for solving various problems caused by having large windows. Solutions can also vary according to the conditions. For example, I designed to provide a front yard between the house and the street and planted a Japanese blue oak tree for the “Steel House.” In addition, a steel bar was installed under the eaves outside the aluminum sash so that sudare (bamboo blind) may be hung.

It is often the case in a congested urban environment like Tokyo that the site is enclosed on three sides except the side facing to the street. Besides, the space for a front yard may also be quite narrow. In such a case, I consider the street in front of the site as a part of the open space.

I think that the “Steel House” represents quite well how you see the relationship between the architecture and the city, as well as how you use architectural elements such as lightness and windows. Could you please once again explain this architecture?

Nousaku: This area was developed as a suburban residential area after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. At the beginning, each lot was large, and the environment was full of green, but then these lots were divided into small plots due to the urbanization and the rise in real estate values. As a result, some houses in this area were built in the suburban style with the front yard, but others were small ready-built houses only with parking space.

This particular lot was divided into five plots, each of them is smaller than 100㎡. Small sites mean that it is unavoidable to build houses close to each other, and being close to neighboring houses means that windows of these houses tend to get uncomfortably small. Increasing the number of this kind of houses will make the suburban residential area less attractive. Therefore, I wanted to create a house with a front yard even if it’s small, or a house with a rooftop garden. I wanted to create an open environment in such a small site. With this idea, I began to feel as if exterior walls of a house are firmly closed shells. I started to design a house with a framework of posts and beams. For bays, I wanted either partitions or windows in order to have light structure. That is why I thought of the steel rigid-frame structure.

-

©Fuminori Nousaku Architects

The distinctive feature of the “Steel House” is being able to open all the windows. What is your intention in designing that way?

Nousaku: I have always liked double sliding aluminum sash, and I’m interested in using ordinary things in less ordinary and deviated way. I think that double sliding windows provide us senses of easy accessibility and openness. Fixed windows cannot be opened and thus give us a sense of closedness although they are transparent. In Japan, slide-to-open style is common for doors and windows, and everyone knows how to use it well.

That is a very contemporary sense, isn’t it?

Nousaku: I have a feeling of creating architecture with a mix of the old and new, instead of creating novelties you have never seen before. I believe that double sliding windows have existed since the early Showa Period (around the 1930s), and it would be as a part of history or custom. It is, for example, efficient and low-cost for building wooden architecture according to Shakkanho (Japanese measuring system), and I find it very interesting to get involved with such cultural and customary rules. Elie During, a philosopher, advocated an idea of “Retrotypes.” He describes that the past should not be handled as a sense of nostalgia, but should be retroactively involved with what we have now, and that the past can also draw a possible future by being directed in a different way. Therefore, we always feel “the past” of design and can handle it not negatively but creatively. I suppose that the past is always a resource for drawing the future.

In the sense of combining and mixing the old and new to produce things, “Guest House in Takaoka”(2013) that will be presented at the Venice Biennale seems to be interesting.

Nousaku: The project, “Guest House in Takaoka” is a project to renovate my parents’ house in Takaoka city in Toyama prefecture, and to create my grandmother’s residence and a guest house where her family and friends can stay. In this house, the grandparents, parents, and their children for three generations used to live in the past, but now my grandmother lives alone. Since it is too large as one person’s residence, it is a project to convert a part of the house into the dining room and the guest room where her family and friends can get together. 40-year-old existing building has the tiled roofs. It is going to be partially dismantled and repaired, rather than dismantling and reconstructing the whole. Then, the materials occurred from the dismantling will be reused in the next repair, and the architecture will be built by this step-by-step material flow generated on site. The project is located in an ordinary landscape of the residential area in the countryside, with the mixture of old houses with tiled roof, new ready-built houses, and the remained rice fields. Tiled roof is an ordinary element, especially surrounded by numerous houses with tiled roofs, but it is an element that has been shared for a long time by the local people. If an architect wants to create the newest form that we have never seen before, the tiled roof would be an obstacle. For me, the ordinary things seem to be important in the local landscape.

In the sense of combining and mixing the old and new to produce things, “Guest House in Takaoka”(2013) that will be presented at the Venice Biennale seems to be interesting.

Nousaku: The project, “Guest House in Takaoka” is a project to renovate my parents’ house in Takaoka city in Toyama prefecture, and to create my grandmother’s residence and a guest house where her family and friends can stay. In this house, the grandparents, parents, and their children for three generations used to live in the past, but now my grandmother lives alone. Since it is too large as one person’s residence, it is a project to convert a part of the house into the dining room and the guest room where her family and friends can get together. 40-year-old existing building has the tiled roofs. It is going to be partially dismantled and repaired, rather than dismantling and reconstructing the whole. Then, the materials occurred from the dismantling will be reused in the next repair, and the architecture will be built by this step-by-step material flow generated on site. The project is located in an ordinary landscape of the residential area in the countryside, with the mixture of old houses with tiled roof, new ready-built houses, and the remained rice fields. Tiled roof is an ordinary element, especially surrounded by numerous houses with tiled roofs, but it is an element that has been shared for a long time by the local people. If an architect wants to create the newest form that we have never seen before, the tiled roof would be an obstacle. For me, the ordinary things seem to be important in the local landscape.

-

Guest House in Takaoka, 2013 ©Jumpei Suzuki

My grandparent had worked on the traditional copper wear production in Takaoka, so in our house, some things remained such as the copper brazier, incense burner, paperweight, and ornaments. Transoms with wood carving in the sitting room and Yukimi-Shoji (screens with a vertical viewing panel) evoke nostalgic feelings for our family. The tiles and stones from the existing moats, exterior walls, and the earthen floor are going to be reused for the pavements covering the garden. If you wish a totally new building, these might be old fashioned and something too nostalgic. However, the copper wears in our house refer to traditional industry in Takaoka town. Also, transom, Yukimi-Shoji, and the garden evoke the memory of our family. Rather than discarding such kind of things, we would like to carry them on to the future, because it is the way we live in the passage of time and in history.

The exhibition theme of Japan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale is “en: art of nexus.” What would you like to transmit to the world?

Nousaku: The general theme “en” contains three subcategories of “en in human”, “en in things”, and “en in local communities.” These “en” cannot be definitely divided, and they are interconnected. My work will be exhibited with the sub-theme “en in things.” Speaking especially about “en in things,” the works will be presented with the character connecting various phenomena, mediated by things.

It is interesting the word “en” has the meaning “contingency.” The reason why things exist can be explained only by contingency. Thus, I think it is important to accept them and bring them in a good direction. It seems very intolerant to break down the existing matters and create something new as it means to plan a totally controllable world without accepting the contingency.

Talking with Masatake Shinohara, a philosopher, I understood that the “things” have been focused on not only in architecture but also in the field of philosophy and theory. In the disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake, I saw the things broken down that had been considered perfect, and I think of the numerous things once balanced and related closely to each other get dissolved and turned into various elements. The things that architects have dealt with have served as tools to create forms and images. After the Great East Japan Earthquake, we recognized that the things can be dissolved and combined, and its network creates a place to live. Interests in things transferred from the meaning of the forms and images to the potential relationships that they generate. This recognition is not appreciable only after the earthquake, but perceiving things as a network also has a possibility of leading to the new ecological theory. Ecology is a biological field based on the interrelationship between creatures and environment. When we create architecture, it would be required to consider where the things that consist architecture come from, and how they affect.

The word “element” is now frequently used, such as in the exhibition of “Elements of Architecture” in the Venice Biennale two years ago. What do you think of elements, including the window?

Nousaku: Element can be interpreted by the idea of “Network of Things.” That is to know what material the element is made of, how the element is produced, and what social or cultural system the element is in. The aluminum sash, for example, is composed of a number of complex factors including the manufacturing technology, the relationship with a country where the aluminum is exported from, electricity supply, and how easy it can be recycled. Such network changes rapidly according to social conditions.

Meanwhile, it is important to see the element including a window as a part of ecology. A window is an element which can be particularly influenced by natural phenomena such as sunlight, heat, wind, and rain. At the same time, people’s behavior or state of mind can also relate to a window when they have a view from the window, work by the window, get refreshed by looking out of window and so on. In ecological psychology, there is a term “weather world.” Weather means the state of the atmosphere, an English word representing “sky” and “air.” When used as a verb, it means “to change” or “to shift.” I believe that the window is an element which perceives such “weather world”, because it can provide a frame for the fluid world. The window can deliver the power of connecting heterogeneous things when the window is free from the perception of being transparent or the continuity of the state inside and outside of the window.

Finally, could you tell us about your most favorite window?

Nousaku: The most favorite window… it’s difficult to choose, but I can never forget the windows of ” Lunuganga”, designed by a Sri Lankan architect, Geoffrey Bawa. When I went through the jungle in the muggy heat of the tropic, there it was, standing in the silence of the morning haze. The windows of Lunuganga are either windows that are always open, openings without any glasses, or louvers for releasing the heat. Because the house is not entirely enclosed, you can hear birdsongs and the sound of trees swinging in the wind. It was a feeling of being inside and outside at the same time, sharing a space with various things. I strongly sensed the weather world in that experience.

Fuminori Nousaku

Born in Toyama prefecture in 1982. Graduated from Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2005. Finished Master course of Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2007. Worked at Njiric+Arhitekti from 2008. Established Fuminori Nousaku Architects in 2010. Finished Doctor course of Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2012. Assistant professor of Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology since 2012.

http://nousaku.web.fc2.com/

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Exhibition “Present State(ment)”

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

House at Komazawa Park

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Boundary Window

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Sunny Loggia House

27 May 2016