Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 2: The Buried Black Roofs : Orchid Island (Part 1)

11 Nov 2021

While we may often speak of “Taiwanese people,” people belonging to a variety of ethnicities and religions live in Taiwan. While I flew to Taiwan’s main island for this installment, I’d like to write about one of its outlying islands.

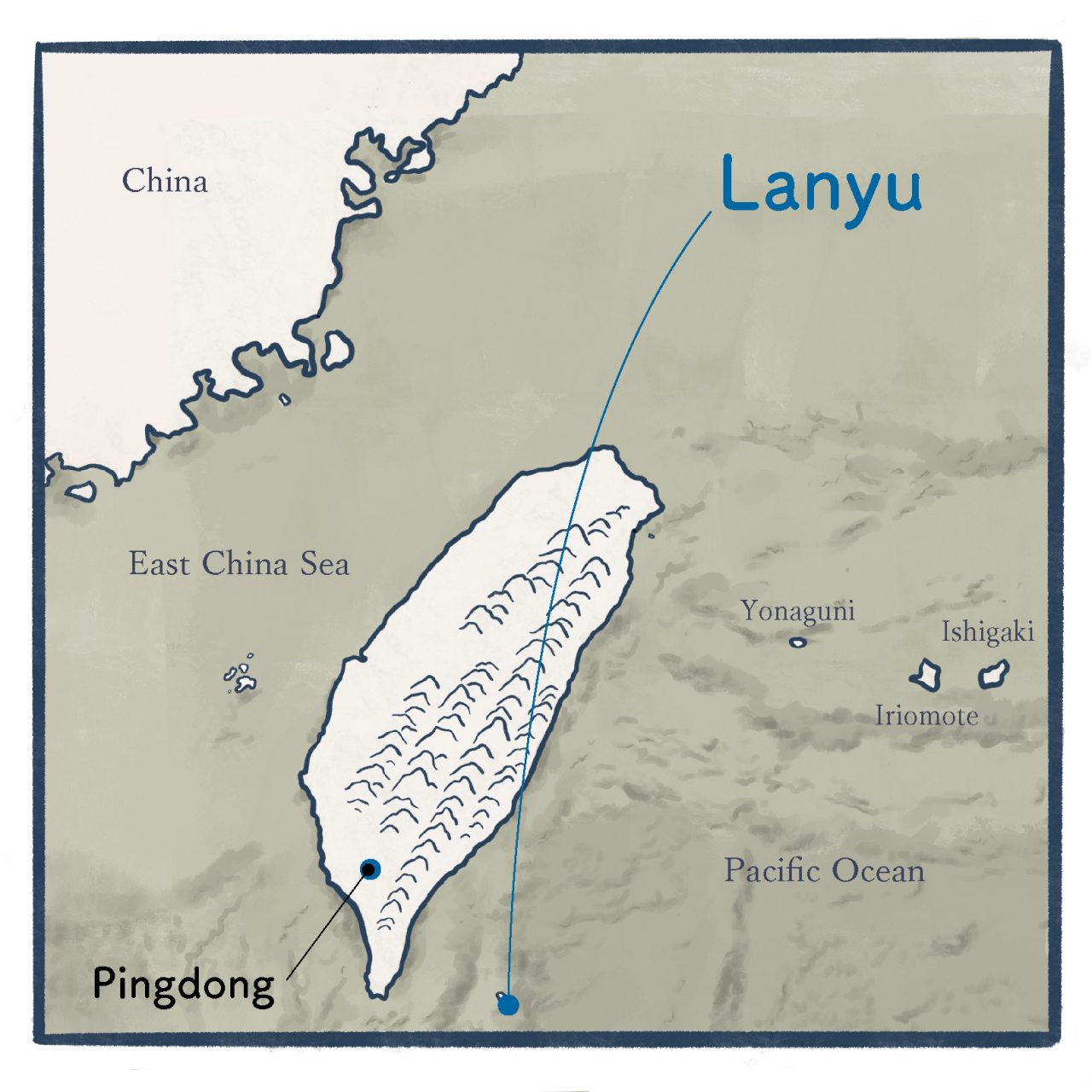

A small volcanic island floats in the Pacific Ocean around ninety kilometers southeast of Taitung, a city in eastern Taiwan. Known as Orchid Island, it has long been inhabited by the indigenous Tao (or Yami) people, who hunt flying fish. It is now also a lively tourist destination, known as a spot for diving. Though the term “indigenous Taiwanese people” is used to describe a number of ethnicities who lived on the islands prior to the 17th century, when many immigrants came to the islands from the Chinese mainland, the Tao people are the lone ethnic group that does not live on the main island.

Getting to Orchid Island is a bit of work. It takes about two hours to cross the Kuroshio Current and travel there by boat from Taitung.

I boarded my boat early in the morning from the port and found that its air conditioning was unusually strong. The plastic bags prepared for us on the seats and the number of large buckets in the aisles gave me a foreboding feeling about the severe journey ahead. I’d asked at a pharmacy for powerful motion sickness medicine, so I swallowed it with a prayer, took my seat, and closed my eyes.

I began to hear the voices of those falling victim to the trip once the boat really began to sway. Crew members scurried through the aisles, replacing now-used plastic bags. I’d prepared myself for this, but what a dreadful world it was. I readied myself for the worst when the Tao boy sitting next to me began to lean against my body, but fortunately I was able to disembark on the island without incident, as did this quietly napping child.

-

The sea from Orchid Island

I’d taken my rocky journey to Orchid Island for one reason: to see the homes of the Tao people. Their traditional residences are known in Chinese as “underground houses,” or dìxiàwū. I heard that in order to withstand the frequent typhoons that come to the island, they’re buried half-underground. I headed toward the village of Yeyin, where these houses still exist, traveling down the sole road that circles the island by motorcycle.

When I arrived at the village, I found large roofs buried in the ground, as well as smaller huts dotting the landscape. Work had been done to create stone walls as the terrain around all these houses. Together, they acted to defend against typhoons. I’d never seen anything like it before.

-

A Tao village. The houses and the terrain around them have been built to complement one another.

It wasn’t long at all before a Tao woman asked if I’d like to visit her home. It seemed that she acted as a guide for tourists as a way to help pay for her living expenses. I asked her if she would, and so she showed me the dìxiàwū where her parents still lived.

She and the others rarely wore traditional clothing apart from special occasion and spoke Chinese day-to-day, rather than the Tao language. This made it easy to communicate with her. It seemed that more elderly people on the island who received a Japanese education spoke Tao and Japanese, middle-aged adults spoke Tao and Chinese, and children spoke only Chinese, making it difficult for the elderly to speak with children. However, this situation isn’t particularly unusual in Taiwan.

I, my friend who accompanied me, and a curious old lady who’d come from the main island on her own followed the woman into the village.

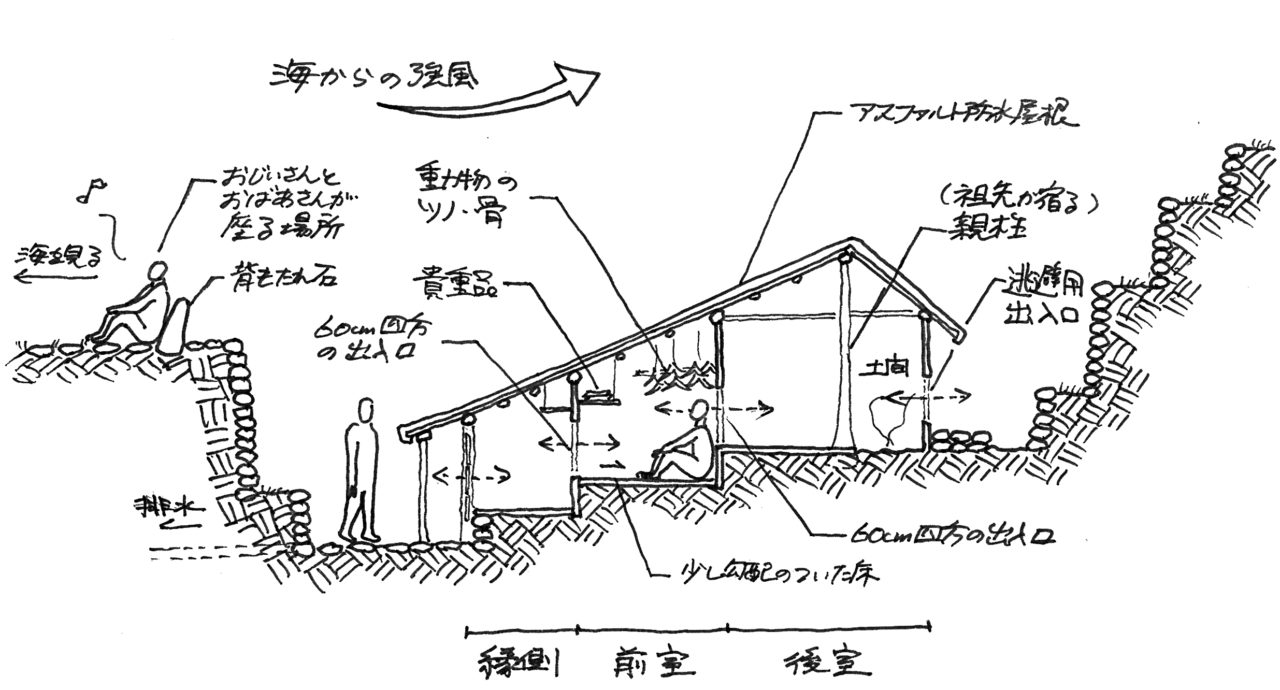

We could only see black roofs from the road, but they were clearly houses when seen from above. Their entrances were located parallel with the ridge of their roofs, and so their eaves were unusually low. The idea of underground houses reminds me of yaodongs in China, but here they felt more like houses that had been placed in holes rather than people simply living in holes. I later learned that in the Meiji period (1868-1912), the anthropologist Ryuzo Torii who surveyed the native inhabitants of Taiwan said that these holes were in fact not dug. Rather, the high ground surrounding them had been man-made. Strictly speaking, then, they aren’t underground houses. Still, it’s impossible to imagine what this village could have originally looked like.

-

An “underground house” standing in a hole created using tiered stone walls

-

The gable is covered in an asphalt sheet, making it completely waterproof

What surprised me was that every one of these houses were black. As defense against 200-plus days of rain and frequent typhoons each year, asphalt roofs and walls painted with coal tar have become the standard. Though photographic records before the war show throngs of thatched-roof houses, the scenery in the village was dyed black after the war.

I took the stairs down into the hole where the dìxiàwū was located, then stooped to pass under its eaves. I found myself in a large, dark veranda. I couldn’t even stand because of its low roof.

From the veranda, I entered inside through an opening similar to a crawl-through entrance found on a traditional Japanese tea house. A sixty-or-so centimeter square, it was barely large enough for a person to fit through. It was even a sliding door that the wind could not open, a choice made with typhoons in mind.

-

The dark veranda

The plank-floor room I entered into from the veranda was another thin, long strip, this one where the family slept.

Our guide told us about times from her past. Due to the particularly cold sea breeze in the winter, children who want to use the toilet at night can’t go outside. To address this, it seems they opened up a small hole in a sloped floor. I discovered a bankbook after a careful look at a shelf located near the ceiling, put there to keep valuables safe from dogs. In order to display the family’s abilities, they’d hung many animal horns and bones from the ceiling. This custom, something also practiced by ethnic minorities in the Philippines, speaks to their connection to people to the south.

-

Looking from the veranda into the front room and beyond

A rear room located another step up had both a planked-floor area and a dirt floor space with a sunken hearth. They use it to smoke flying fish and meat. It’s rare to find a house whose furthest room from the entrance is unfloored, but they prevent filling their home with smoke by placing the kitchen higher than the rest of the rooms. Even then, the inside of the house was covered in soot. Looking carefully at the walls, I could see the Tao carvings there shining black.

The room also contained a center pillar with a broad base made using thin planks, thought to be the column where their ancestors dwell. Though houses are demolished once the father of a family dies and the lumber is divided between the children who use it to build houses of their own, this pillar seemed to have been inherited by the family’s eldest son.

-

A profile sketch of a Tao dìxiàwū

-

Engravings on a wooden wall. It seems that the jagged lines represent waves, while the vertical lines represent ribs.

Behind this central pillar, which is to say at the rear of the house, is another small entrance. Apparently, it is an emergency exit in case the home comes under attack. Orchid Island once contained twelve villages (compared to six now), and conflicts would occasionally break out between them over fishing rights, water usage, and more. A semi-transparent board now blocked the opening, telling me that such strife had come to an end.

-

The center pillar where ancestors lie, as well as an escape hatch

These low, dark “underground houses,” which require the sacrifice of something as basic as being able to stand inside one’s home, are rapidly becoming a thing of the past. Our guide left home at the age of twelve and now lives in a concrete house known as a “cement house (pinyin:shuǐní wū).” What will change with their appearance, and what will remain? I heard of a village that had demolished most of their traditional house, so I went there next to find out.

(Continued in part 2)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda University’s Nakatani Norihito Lab with his master’s in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window“). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Culture’s overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda University’s Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window“). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Culture’s overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 16: Red Bricks and Bullet Holes : The Kinmen Islands (Part 1)

18 Dec 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 15: The Folk Spirit Dwelling Within Decorative Window Grilles

22 Jul 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024