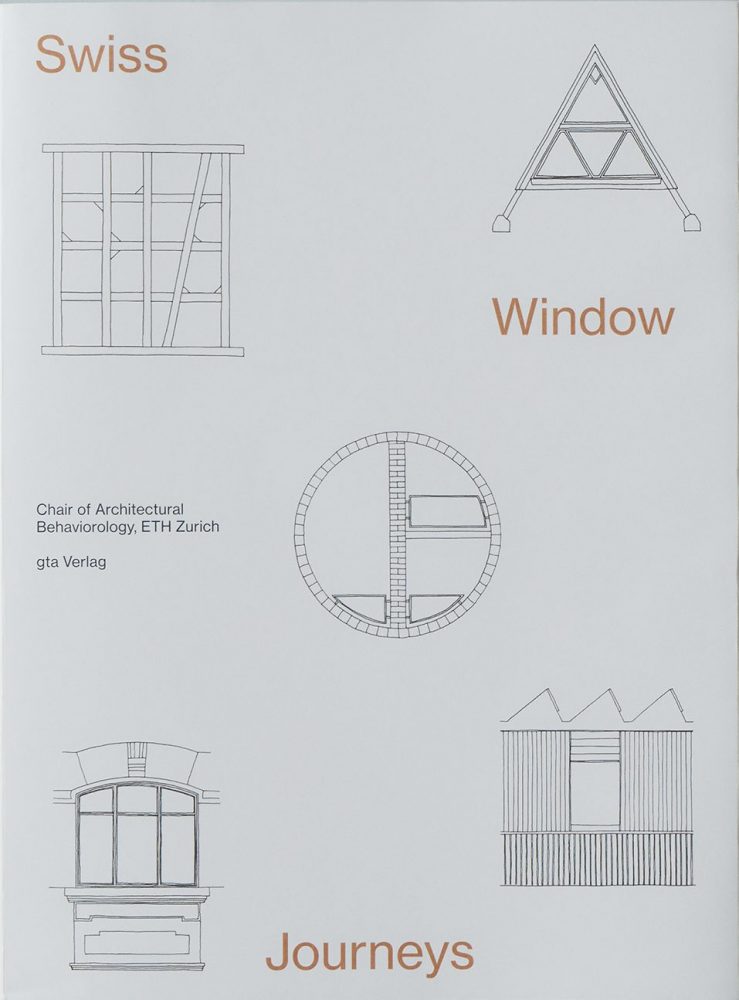

Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Gion A. Caminada

15 Feb 2021

Vrin is a village of fewer than 250 people nestled in a lush valley in the canton of Graubünden in eastern Switzerland. It is also the home of architect Gion A. Caminada, who has designed many buildings for the village, from the village hall to the slaughterhouse to the mortuary. The unique landscape of this region has been shaped with architecture using the traditional wooden block construction called ʻStrickbau’, Mr. Caminada has continued to develop this architectural culture in his designs in an attempt to connect them to the present.

The Chair of Architectural Behaviorology led by Professor Momoyo Kaijima interviewed him about the role that architecture and windows should play in the Swiss village in transition.

Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (CAB): Our research focuses on the window in Switzerland, on how its form and design are influenced not just by the country’s diverse landscapes, climates and cultures but also by developments in technology and, particularly in recent decades, by growing concerns about the environment and energy consumption.

The character of Swiss villages has also changed substantially, for example with the advent of tourism in the Alpine region and with modernization, which brought a shift in scale through the mechanization of production. The socio-economic conditions resulting from these changes pose new architectural challenges: building types have to be adapted to new uses, or new types have to be introduced to respond to different lifestyles.

We’d like to discuss these topics with you in relation to your practice in the context of the Swiss village, and especially Vrin. What challenges do you face? How do you think we should understand the window in the context of the village?

Gion A. Caminada (GC): Windows used to be relatively small in Vrin, as in most other places. Of course this had to do with technology, with the size of the panes and the difficulty of insulating the glass. But I think it was also in some way connected with people’s livelihoods. I’ve never yet heard a Vriner say that the landscape is beautiful. The landscape is just the way it is.

-

The scenery of Vrin from G. Caminada’s office : ©︎ Chair of Architectural Behaviorology

Before, the villagers were living and working in the landscape every hour of the day. Now we have a lot more free time – and a completely different relationship to the landscape. We think it’s under our control, so to speak, subjugated by technology. We can have big panoramic windows, as if that would bring us a little closer to nature. I’m a nature lover, but when I look through a big panoramic window I see the world as a picture – a picture that has no story to tell, but is just an aestheticized view of the landscape.

I’m not saying that you should only have small windows in Vrin, or that no one’s interested in the landscape. That’s not true. I think the people who come here from outside do want to look at the mountains, whereas the locals are perhaps more interested in watching television. So the window is bound up with your idea of how you want to live.

Perhaps the most fantastic thing about Vrin is the way it has grown organically. Architecturally, not all the houses are good – some are even bad – but that creates a mass of equivalence, doesn’t it? Almost always you have a mass of wood with just tiny differences. And it is precisely this continuity – this portion of things that are almost the same – that gives the village such a powerful cohesive character. Windows naturally play a part in orchestrating this whole, with the newer buildings having bigger windows and different types of glazing.

-

Mazlaria, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–1998 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

In the mountains you have to find the right relationship between the window and the wall. I think a wall surface area of around 40 per cent would allow for a good balance over the years, because today we’re not only having to deal with the cold, but with overheating.

It’s a huge problem – and one we have to find architectural solutions for, rather than continuing (scandalously) to rely solely on technology. When we plan a building, we need to be thinking about the different climate zones that come with the orientation, clearly. And we need to be taking people with us, showing them there are other qualities at play. Then attitudes may change – even attitudes towards the window. When a client tells me they want big windows and I don’t think it’s such a good idea then I’ll talk about the space. What will this do for the feeling of the space? What’s important to you about this space? (Sometimes then, the choice of a big window will turn out to be the right one.)

When we talk about windows, we’re also talking about space. Architecture is above all about making good spaces, and the window is part of this. And that’s perhaps why a window in Vrin shouldn’t be the same as one in St. Moritz or Horgen or Herrliberg or wherever. It’s not just about climatic conditions; it’s also a cultural matter: how do people live in a place? How do they relate to the landscape?

CAB: The changing lifestyle in the village also poses new architectural challenges in terms of introducing new building types that can respond to the shifting demands of society—like in the case of the multipurpose hall in Vrin. How did you approach this engagement with an entirely new typology?

GC: I think this kind of hall must have existed in earlier times too – at least with regard to some of its functions. Anyway, the hall is a public space for the whole community and it’s the only one of its kind in Vrin, so it has to look different, just as the church and the house and the stable all have to have their own distinct appearance. One of its functions is as a sports hall, so it has clerestory windows on two sides, while three smaller windows on the third side precisely frame a small slice of the landscape, setting up a direct visual connection between the building and the village. The roof system also makes use of local timber with an unusually large cross section.

-

Vrin Multipurpose Hall, Vrin, Switzerland, 1992–1995 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

-

Vrin Multipurpose Hall, Vrin, Switzerland, 1992–1995 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

-

Vrin Multipurpose Hall, Vrin, Switzerland, 1992–1995 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

But to answer your question about working with a new typology, I’m interested in taking Strickbau [the wooden block construction typical of the region] in a different direction, giving it another kind of aesthetic expression, one that could be somehow “ennobled” for cultural buildings, for example. Thinking about the essence of Strickbau, I realised you could achieve a greater plasticity. The arrangement doesn’t have to be cellular units stacked on top of each other – those basic units can intersect, with more of a play between closed cells and interstitial spaces (the method Peter Zumthor used in developing the Thermal Baths). Externally, this makes for a more sculptural effect. The Strickbau wall has such strength, such solidity, that it feels to me as much a psychological space as it is a physical one.

CAB: The Strickbau system is certainly an important theme with regard to your approach to windows.

GC: In Strickbau, the window is one of the main themes, I think, along with the roof and the base. It’s an important element. Of course, I have to take different things into account when I’m doing Strickbau, and consider the relations between the solid and the open parts of the building.

-

Stiva da Morts, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–2002 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

-

Stiva da Morts, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–2002 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

Strickbau is often thought of as functioning like a concrete wall. That’s not so. Each timber block is like an independent beam. So it used to be like a “game” for me, a question of how big an opening I could make in the wall before the timber blocks started to sag. You had these energy strategies – fortunately, I think we’ve managed to move beyond those times a bit – that said you had to enclose everything in a U-shape and then cover the front facade in glass. And suddenly you had something like a cave. That doesn’t work here – it doesn’t create a good living environment.

On the other hand, in the city today, you don’t have windows anymore – just “glazed surfaces”. We need to start building windows again. They speak to the human dimension, they’re something to be handled. By now it’s also clear that air-conditioned buildings with no natural ventilation are bad for people’s health.

CAB: Another project that emerged in response to social change is Stiva da Morts. Elderly people started to spend their retirement period in sheltered housing or nursing homes, which meant that private living rooms were no longer available for the traditional mourning period after their death. So the villagers demanded a community mortuary. Could you tell us about the idea of the window in this project, and also how it relates to Strickbau construction?

GC: In the community mortuary [Stiva da Morts, Vrin, 1995–2002] the windows are quite narrow and they’re set into the wall in such a way that the people inside are concealed from view. If you take just a few steps to the side of the window, no one outside can see you. This anonymity – this ability to hide – was incredibly important with the Stiva da Morts.

There are two Strickbau walls and the windows, set in their deep reveals, are the element that ties them together. The windows are also double-layered – the ones set flush with the inner wall are openable, while the ones on the outer facade are fixed and have protruding frames. So the window has a constructive rationale but at the same time it always relates back to the question “What is the room for?”

-

Stiva da Morts, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–2002 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

-

Stiva da Morts, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–2002 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

And here I said I want to make a space where I can withdraw, a place of mourning. I might still want to see something of the outside world, but I also want to hide from the world at this moment. I found these narrow windows where you can mould the view with simple body movements – and practically hide in the window, something you could never do with a horizontal window. The first question is always “What would make for a good space, in terms of the role it has to fulfil?” And the window supports this spatial idea, along with other elements such as the choice of materials or the lighting.

This is more than an aesthetic question: “Do I like the way this looks?” It’s about inscribing meaning into space. That’s extremely important to me. Rather than focusing on the aestheticization of surfaces we need to be talking about meanings that can define the whole development of the window, its position, its handling, its functionality. We don’t start out knowing exactly how to do it; rather, the whole beauty lies in the process of developing it. And however we develop it, the basic idea should not be idiosyncratic, a personal whim, but should have a wider resonance. It should have something to do with the culture of the place – but not in the sense of simply repeating what is already there.

CAB: Talking about building types, your descriptions of the Stiva da Morts often mention that you chose a pyramidal roof to distinguish it from the houses in the village, with their gable roofs. Is there an equivalent approach for the element of the window in relation to specific typologies?

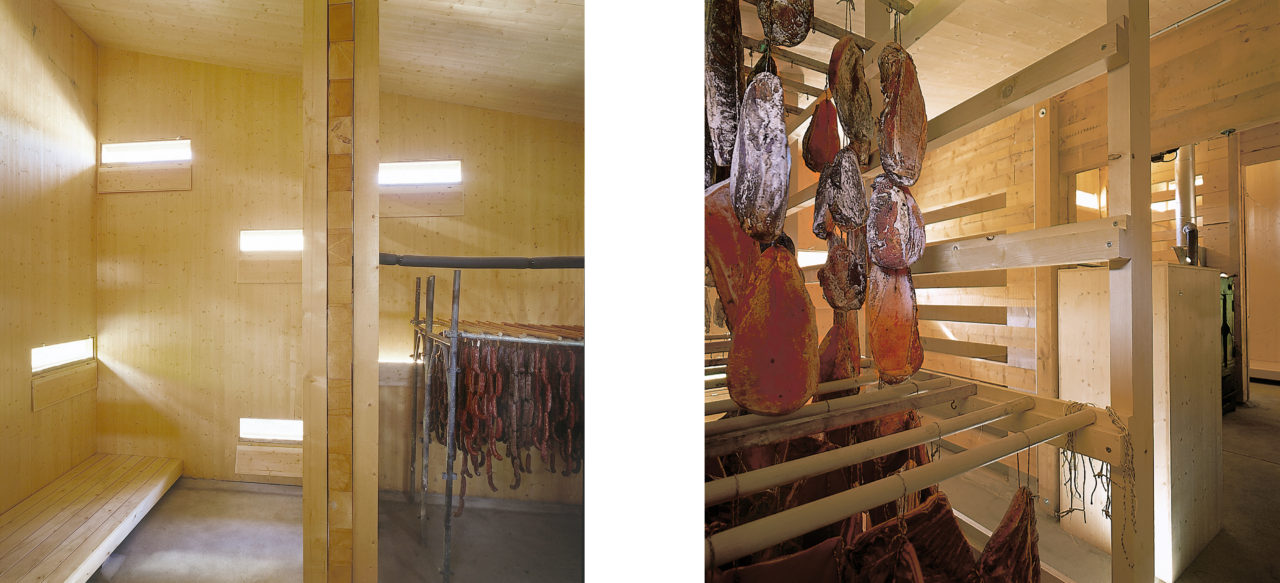

GC: I think the human dimension is very important here. How are the windows to be used? With stables, for example, the opening in the wall is more about letting in light, but I wouldn’t use that kind of window for a house. By contrast, the cooperative butcher’s [Mazlaria, Vrin, 1995–1998], has little openings to let in fresh air as part of the meat-curing process. Added to this, there are of course openings that are an integral part of the structure, that define the character of a space.

-

Mazlaria, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–1998 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

-

Mazlaria, Vrin, Switzerland, 1995–1998 : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

So, as I said, the typology is important, but just as important is the specific location. What kind to choose is something you have to decide from case to case. There’s no “right” window for a particular role – fortunately. In each instance I try to define what’s powerful in a particular situation and to build on that, make it stronger still.

But there are certain windows I would never build in Vrin, because they would undermine the palpable cohesion of this place. Of course, any fool could build a glass ball in the village. That would be easy. What’s much harder is to build in continuity with the existing fabric in a way that strengthens it and carries it forward.

CAB: And do you work with local makers or craftsmen for the construction of windows in your projects?

GC: We have a good carpenter’s workshop in the village, so we’ve always done the windows ourselves. Of course, the glazing now has to do a lot more than it did in the past. There are huge variations of temperature here, and the window is naturally a very exposed element. You have to think very carefully about its production.

CAB: Another topic that emerges strongly with the shift in the village’s way of life – besides the introduction of new building types – is the transformation of existing typologies to serve new uses. For example, in your recent project in Fürstenau, Casa Caminada, you’ve converted a series of stables into a guesthouse, introducing new elements in the form of the loggia on the upper floor, with the concrete infills of the balustrade and new types of window frame. We can imagine that these new elements enrich the interior life of the building.

GC: There are incredibly beautiful views from the Casa Caminada, for example, so the windows there come right down to the floor.

We had a real battle with the conservation authorities over the timber cladding. I told them, “Behind those planks you used to have hay or animals, but you’re not going to have animals in there anymore – only people – so they have to go.” To be lived in, the building has to adapt.

-

Casa Caminada, Fürstenau, Switzerland, 2018 : ©Hans Danuser

-

Casa Caminada, Fürstenau, Switzerland, 2018 : ©Hans Danuser

We live with the house and the house has to live with us – it has to change as we do. The things that we live with can have an incredible resonance. For me, resonance is different from an echo. An echo is when you call something and it comes back, whereas resonance has to do with the transformation that occurs when the material absorbs what you put into it – allows it to penetrate. The photographer Hans Danuser has said that photography is about the depth of the surface. In other words, there are some materials that resonate, that invite our eye to linger, and there are others that repel the gaze.

CAB: And what about the openings in the stone base of the building? Wouldn’t they originally have been much smaller, intended only to let in some light and air?

-

Casa Caminada, Fürstenau, Switzerland, 2018 : ©Hans Danuser

GC: True, and it’s this ground floor that ties the different parts of Casa Caminada together. The repetition of the tall openings has a powerful unifying effect. There’s also something metaphysical about it – like a de Chirico. It’s not an image I intentionally set out to create, it was simply there. But I still find it very beautiful.

It was important to me that the conversion should create a different typology – move away from a stable. So, you can make changes, but they shouldn’t be so strange. They should have something familiar about them, even if you’re using different forms. You have to feel, ʻI know this – even though it’s different.’

CAB: Casa Caminada’s conversion into a guesthouse links to another major shift in the Alpine region: the advent of tourism. In the early modern period this shift introduced a new and unprecedented scale to village communities, with the typology of the ʻGrand Hotel’, for example…

GC: I’ve always thought the tourist industry was built in a kind of dream world. Those Grand Hotels were just terrible – huge alien bodies in little villages. The English, the early tourists in Engadin, essentially brought those hotels with them. In the past you had very little that came from outside, and a lot that was your own. But now in architecture you hardly have anything of your own tradition anymore – just buildings thrown together using components from the international construction market. Perhaps that’s the nice thing about Vrin. Each building is like an autonomous creature, with an independent personality. It contributes in its own way to the community. Each building stands for itself and yet is part of the whole village.

-

©︎ Chair of Architectural Behaviorology

Gion A. Caminada

Gion A. Caminada lives and works as an architect in Vrin and is a full professor of architecture and design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at ETH Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan’s Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba since 2009, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), and Columbia University (2017). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city through publications such as Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia.

Christoph Danuser

Christoph Danuser (b. 1988, Chur CH) joined the Chair of Architectural Behaviorology in 2018, where he is involved in research and teaching for the chair’s design studios. After studying architecture at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and ETH Zurich, from which he graduated with a master’s degree, Christoph worked for several years as a project leader and gained experience designing and developing multiple projects of different sizes and kinds, from new developments to the renovation of listed buildings. In 2018 Christoph founded his own architectural practice, Atelier Danuser, working on architecture projects in Switzerland and abroad.

Simona Ferrari

Simona Ferrari has been a teaching and research assistant at the Chair of Architecture Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) since 2017 and works independently as an architect and artist. She studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, TU Vienna, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology as Monbukagakusho Fellow. From 2014 to 2017 she worked with Atelier Bow-Wow in Tokyo, completing several international projects. She is currently pursuing an MA in Fine Arts at the Zurich University of the Arts. Ongoing projects include the winning proposal of Europan 15 for the former industrial site of Acetati in Verbania, IT (with Metaxia Markaki).

Top image : ©︎ Lucia Degonda

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Swiss Window Journeys: A Conversation between Andrea Deplazes, Laurent Stalder, and Momoyo Kaijima

17 Dec 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Silke Langenberg

25 Jul 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with François Charbonnet (Made in)

25 Jan 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Christine Binswanger, Raúl Mera (Herzog & de Meuron)

24 May 2023