Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Shifted Windows: Masuleh, Iran

03 Dec 2019

There is a small village in the valleys of Iran known as Masuleh that has stood there for over a thousand years. Its tiered homes are built along the mountain’s steep face, and it seems to also be famed as a tourist destination, with its unique townscape where one cannot tell if they are looking at roofs or a street.

However, there seemed to be few people around when I visited one winter morning. I will wait for another opportunity to speak about the relationship between roofs and streets in Masuleh, as I would like to note here the thoughts I had when seeing the village’s windows.

-

Masuleh, where roofs act as streets

If you were to divide architecture into structural elements, such as walls, pillars, and roofs, and other elements, then windows may be the most notable example of the latter category. The facades of the structures I saw in this village made me think about exactly how windows stand independently from the rest of architecture.

For example, I saw wooden-framed windows of various shapes and colors with a wealth of expression inset on the façade of a sun-dried brick house where it appeared as though three homes have been stuck together. Octagonal colored glass, curved lines that bring to mind Japanese kara-hafu gables, windows with embossed boards, and other such designs are varied in a way that makes one feel a wide range in time.

While there are various other designs to be found in the village’s windows, the geometrically patterned designs one might expect to see in an Islamic village stood out to me. The thin, wooden lattice windows are known as mashrabiya, a uniquely Islamic design said to be created in order to fulfill multiple functions, as they soften outside light, allow wind in, and let women inside safely see what is outside.

-

The various windows in the village of Masuleh

While it seems they were popular in Egyptian homes, windows made from finely carved slabs with similar functions can also be found in the palaces of India, showing that the design spread far throughout the Islamic world. Islamic traditions seemed to be still quite alive in this village as well. The windows’ minute decorations were more than enough to give individuality to the dull, ocher, mud-plastered walls.

As opposed to structural elements, where materials found in nature can be used as they are to some degree, whether stacking up stones or erecting and lining up trees, one unfortunately cannot find stones already in the shape of a window, nor are there trees that grow window-shaped. In order for a window to exist as a window, work must be put into it with human hands to one degree or another.

In areas where materials for windows cannot be gathered, windows seem to create an opportunity for outside culture to be introduced. This village has a history of once prospering as a producer of sharp instruments, and windows must have come to it from the outside as goods circulated. The monk homes I saw in China’s Larung Gar contained lines of shining mass-produced aluminum sashes inside the self-built, dull-red wooden structures.

-

An alley in Masuleh along with windows of various designs

-

As multiple homes share the same partitioning walls, the boundaries between them are unclear

At times, it can be hard to figure out the boundaries between individual homes among the south-facing houses lining the north slope of the valley that seem to cling there, as they share partitioning walls. The way they each have windows of differing designs, though, tells one that they are looking at different rooms, or even different residences.

To go a little further into the idea that windows are separated from structures, I’d like to think about the way they are renewed.I think we can agree that it’s normal for windows to be inlaid when a residence is being built. However, as they’re opened and closed on a daily basis and touched by human hands, they often break as well. One can easily imagine a situation where a window must be replaced prior to a structure ever collapsing.

There must also the opposite case, where an entire home is rebuilt, either due to damage from a disaster or a family getting larger, but for its unbroken window frames to be reused in a new home.

-

Windows with “shifted” timelines provide contrast to homes

In other words, structures and windows lose their synchronicity as they are renewed with the passing of months and years, causing them to exist in shifted timelines. The sight of Masuleh, with its various types of windows living together, seems to have been created in this way. At the same time, one can also recognize this as a value of the settlements and structures that continue to exist there.

As I walked through the village, I encountered villagers undertaking a once-in-thirty-years repair of a roof. According to them, they were repairing part of the second-floor windows along with this “600-year-old” home’s roof.

-

Inside a home in Masuleh

-

A “600-year-old” home undergoing repairs to the area around its windows

Its walls were over sixty centimeters thick, and I could feel the differences in light let in by the various types of window frames. Parts of its interior reminded me of the strange “niches” I saw in East Gilan. At times, windows were even fated to be covered up.

Even the sight of this construction that I happened across made me feel like I was present at a point in this home’s history when I thought about it this way. A window that will become “shifted” compared to the structure would soon be born in this very home.

Ryuki Taguma

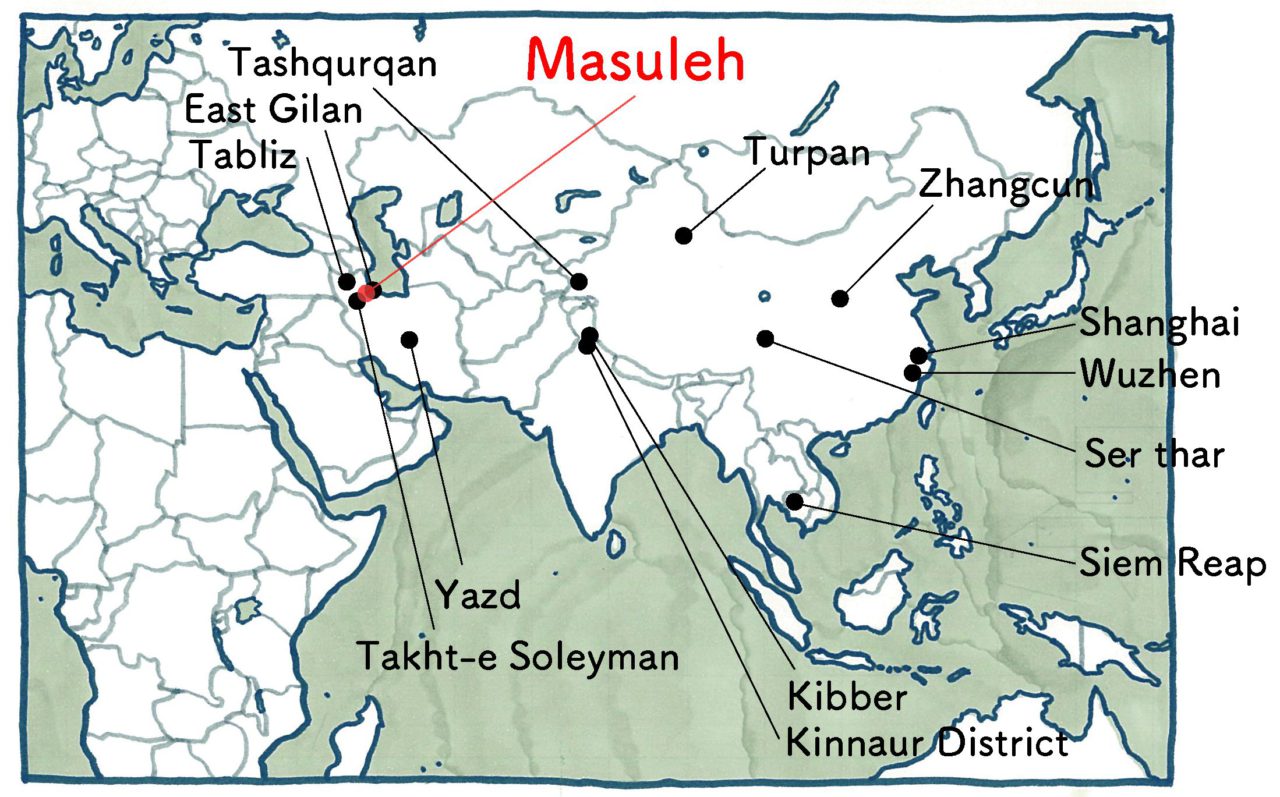

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.