Red Wine from the Terraced Fields of the Bormida Valley

28 May 2019

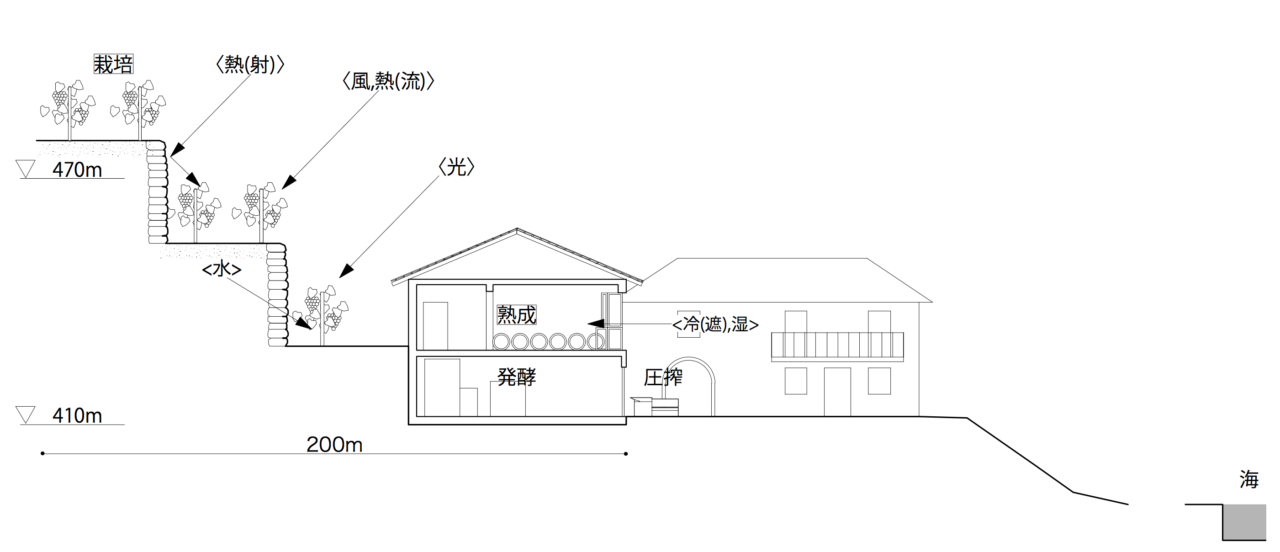

The Bormida Valley is located in the southern part of Piedmont, a region in northwestern Italy located about two hours by car from Genova. Because the valley is at a high elevation of 400-800m, the temperature difference between summer and winter is severe. It is said that the temperature may drop as low as 5℃ in winter.

-

Terraced fields in the Bormida Valley

Looking at the valley, one can see fields scattered on the slopes. Upon closer inspection, you notice that not only are there fields utilizing the slopes as they are, some of them also terraced.

This article is about the red wine that is produced in these terraced fields and registered with Slow Food. I would like to investigate the architectural devices involved in producing wine in these harsh natural conditions.

The museum, called Monte Oliveto, was built in the 11th century on a site where grapes had actually been harvested for the production of red wine. It is said that the terraced fields were created by monks to prevent erosion in the hilly areas and grow crops in this area. The technology to create terraced fields spread from this area to the surrounding land.

-

Fields of Monte Oliveto Open Air Museum

Until the 1980s, “dolcetto,” the kind of grapes used for red wine, used to be widely grown in this area. However, due to population decline, many vineyards had been replaced by land for the mass production of hazelnuts. Then, in the late 1990s, young local wine makers began to produce wine by reutilizing these terraced fields.

Enzo Patrone, who runs a winery in the area of Cortemilia in the Bormida Valley, and his wife Elena, are among these young wine producers.

-

The Patrone family’s fields

“The only way to produce wine in this area, at an elevation of about 450 meters above sea level, was to reutilize these deserted terraced fields,” says Patrone.

Furthermore, no mortar or cement is used for these terraces in the Bormida valley. Instead, they are made up of entirely of Langa stone, a widely excavated stone in the area.

“Generally, in cold regions like Cortemilia, grapes such as dolcetto, the base ingredient for red wine, do not grow. It is Langa stone that has been used there. The grapes are protected from the cold through the radiation of heat at night. In addition, placing the fields on a south-facing slope is useful to get warm wind blowing from the south.”

Thus, the Patrones family has inherited the traditional method of grape cultivation utilizing nature, and continues to produce wine in this area.

-

Grapes growing in the terraced fields

It seems that grapes are still harvested by hand, not machines. Therefore, when harvesting, the producers have to carry around a heavy basket. Arched holes in the masonry walls of the terraced fields are apparently used for resting during harvest season. They also are used for temporarily placing harvested grapes and tools.

-

Archted holes for temporarily storing harvested grapes and tools

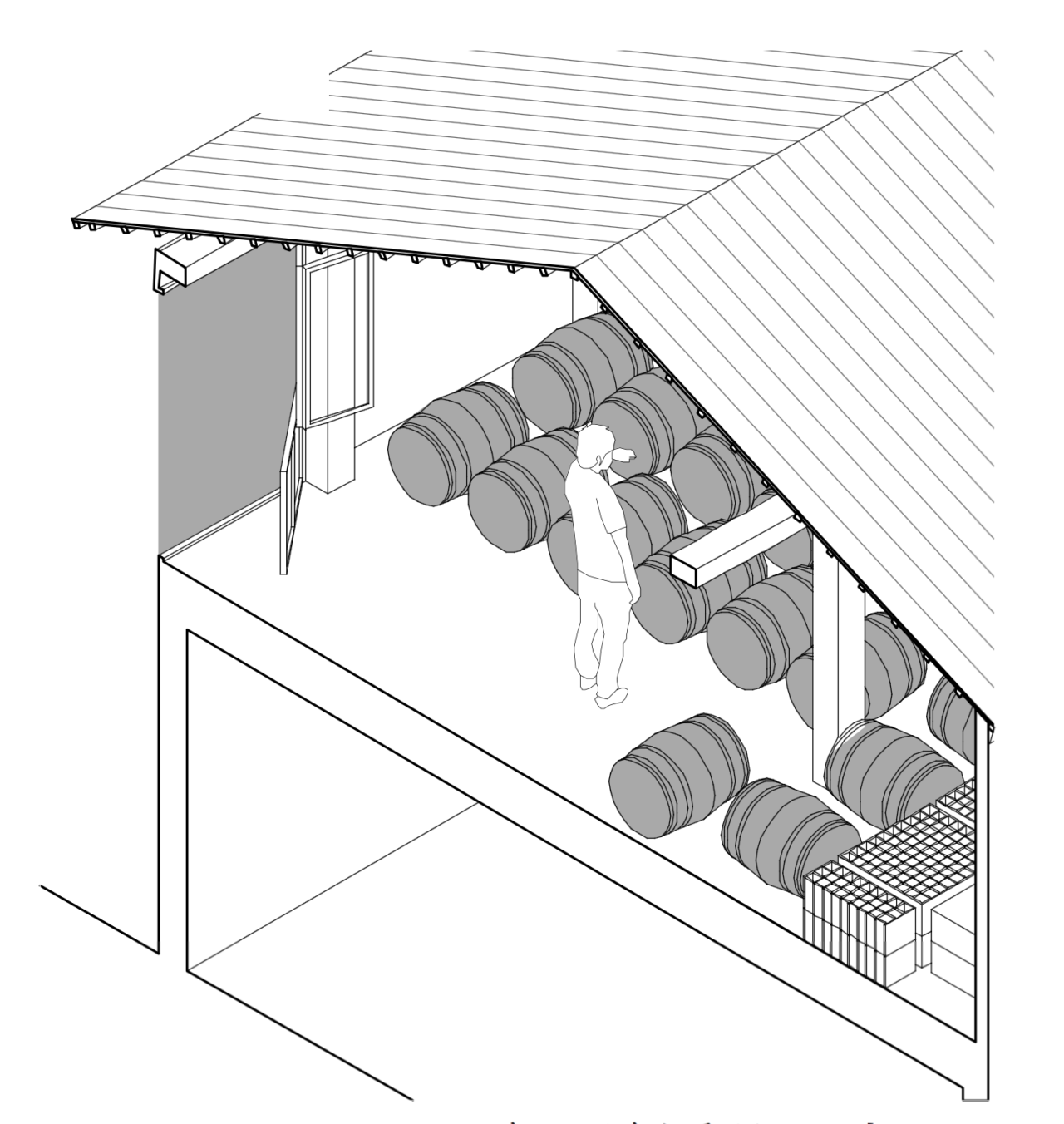

The grapes are then pressed, alcohol-fermented and then aged in the wine cellar. Wine cellars (aging rooms) are usually located in the basement where the temperature change is low. By aging slowly within a room with a stable temperature and humidity, more complex aromas and flavors can be produced.

The Patrone family’s aging room, on the other hand, is set up on the second floor of the building where the temperature changes dramatically by solar radiation from the roof. In addition, Cortemilia is a region where the temperature changes drastically, from 5℃ in winter to 25℃ in summer.

-

The aging room on the second floor of the winery

The Patrone family’s aging room, on the other hand, is set up on the second floor of the building where the temperature changes dramatically by solar radiation from the roof. In addition, Cortemilia is a region where the temperature changes drastically, from 5℃ in winter to 25℃ in summer.

“Aging rooms are typically located in a room with a stable temperature of 10℃ to 14℃, but our aging room is on the second floor, which is easily affected by temperature change. This is because until twenty years ago, we were producing cheese and did not need an underground aging room. So, we have a window in the aging room that allows us to minimize temperature changes—opening the window in summer improves ventilation and lowers the room temperature, while closing the window in winter helps to maintain the appropriate temperature. The windows are an indispensable part of making wine in this place.”

Indeed, there is a large window in the Patrone family’s aging room that allows sun to come in. The room is a bright and airy space that is completely different from the typical image of a wine cellar.

-

Windows are opened by turning the middle handle and opening from the top

The windows are openable and closeable as well. The lower part is doubled inward from the center and the upper part is folded in the middle so that the angle of the window can be adjusted freely. When opening the window, one twists the middle handle to separate the upper and lower windows that had been tightened. In addition, the upper half of the window can be opened further by removing the lock on the hinge at the fold.

Thus, the grapes grown in the Bormida valley become red wine after aging for 12 months. The finished wine is ruby red with a pale purple tint. Blended with berry and spice aromas, it has a faint, grassy aroma.

Production Process of Red Wine

from the Terraced Fields of the Bormida Valley

-

Isometric view of the wine cellar (aging room)

-

Site cross section of wine production in the Bormida Valley

The Bormida valley in Cortemilia is located in a cold area 450 meters above sea level. For this reason, the cultivation of grapes used for wine production is carried out in terraced fields exposed to sunlight and warm air from the south. This terraced field is made of masonry called Langa stone, which absorbs heat during the day and emits heat during the night to protect the grapes from cold air. After the grapes are harvested at the end of September, they are pressed and subjected to the primary fermentation process, and then ripened in the aging room on the second floor of the winery. By setting up and using windows that can adjust at the top and bottom of the window, a stable temperature and humidity is created. This produces red wine with more complex aromas and flavors.

Tomoki Shoda

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1990. Since his father transferred to many counties, he had lived in many places such as France, Indonesia, China and Belgium. Researched about traditional workshops in Japan for “WindowScape3 -working window” in Yoshiharu Tsukamoto Laboratory at the Tokyo Institute of Technology from 2014 to 2015. Studied abroad in Politecnico di Milano from 2016 to 2017. Researched about Italian Traditional food registered by Slow Food from the perspective of architecture. Graduated master course in Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2017. Researched Japanese Traditional food production as Slow Food Nippon researcher from 2017 to 2018. He has been in Takenaka corporation design team from 2018 to present.