Dry-cured Ham Culatello in Zibello Village

28 Jan 2019

At the beginning of November, I drove a car north from Parma and aimed for Zibello village. As I passed through the central Old City, I saw fields and houses scattered around. As I advanced the car further north, it suddenly began to fog all over. Even though it was still 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the road ahead was hazy enough to make it difficult to see without headlights.

Here, Zibello village is close to the Po River, which is the longest river in Italy. The humidity is high, and as the temperature drops, the water vapor in the air becomes a small water grain and turns into small drops of water, so the area gets wrapped in fog during the winter. The fog produced here in Zibello village is a very important natural resource for the production of dry-cured ham Culatello.

-

On the road from Parma to the production facility

The day before I left to study in Italy, I met writer Natsu Shimamura, who wrote “Slow Food Life! – It Starts With the Italian Dining Table” (Shinchosha, 2000) and was a pioneer of the Slow Food movement in Japan. Natsu Shimamura had a experience of visit of many production space and interview with producers. When I spoke with her about going to research in Italy, she said that if I go anywhere, it should be to the village of Zibello, where the production of Culatello takes place.

So, what kind of dry-cured ham is Culatello? As soon as I checked it out on the Internet, I saw that Culatello is called King among the many kinds of dry-cured hams in Italy, getting orders from clients such as Prince Charles and Michelin-starred restaurants.

-

King of dry-cured hams, Culatello

By the way, when you think of Italian dry-cured ham, it is probably Parma Ham (Prosciutto di Parma in Italian) that comes to mind. I would like to explain the difference between Culatello and Prosciutto. While Prosciutto uses the whole thigh meat and hangs pigs’ legs to mature, Culatello uses only buttock part of the pigs’ thighs, hanging it in a net made of strings to be matured. But more than this is the fact that Prosciutto is produced in the village of Langhirano, which is well-ventilated and located along the valley of the mountain range south of Parma, while Culatello is produced in a humid plain, like Zibello village near the river in northern Parma.

Among the areas producing Culatello, those registered with Slow Food are limited to 8 municipalities, including Zibello. All of these are in the plain and adjacent to the Po River. In the summer, temperatures rise above 30°C, while winters vary between 5-6°C. Because the area has high humidity, it gets wrapped in fog in the winter.

-

Production area of Culatello

In such high-humidity areas, dry-cured ham can not be produced in the same way as Prosciutto is produced in well-ventilated and dry areas. Thus, Culatello’s unique method of fermenting and ripening meat with mold generated in high humidity was born. In this way, what characterizes Culatello more than anything else is this production method which uses humidity as a resource.

So, how is this dry-cured ham, which sees only a few thousand pieces on the market every year, actually produced?

This time we were able to visit two pairs of producers out of the four sets of Slow Food producers in Zibello village, which is still producing Culatello using traditional manufacturing methods. Among them, I would like to introduce the production method of “Bre del Gallo,” a facility managed by Alfredo Magnani.

Alfredo’s family has been producing Culatello for generations. The building used for production was originally purchased 50 years ago.

Pigs used for Culatello are selected by Alfredo’s son, a veterinarian, 9-12 months after birth and weighing about 200kg. According to their arrangement with Slow Food, pigs may only be slaughtered within Parma and its suburbs, so Alfredo’s relatives bring the butchered meat to the production facility after slaughtering.

-

Alfredo’s family’s production facility, "Bré del Gallo"

Additionally, in order for the pigs to be processed in a fresh state, the time from slaughter to butchering is restricted to 48 hours. The pigs are thus butchered immediately, and the buttocks to be used for Culatello are salted. For salting, only salt and pepper are used (though, depending on the producer, sometimes wine or garlic is used). After that, the pig bladder is used for filling the bag, the threads are bundled in a mesh form so they do not collapose, and they are let to hang. Unfortunately I was unable to photograph the cooking of the meat, but the traditional recipe, which is time-consuming and requires quite a bit of manual labor, is still used today.

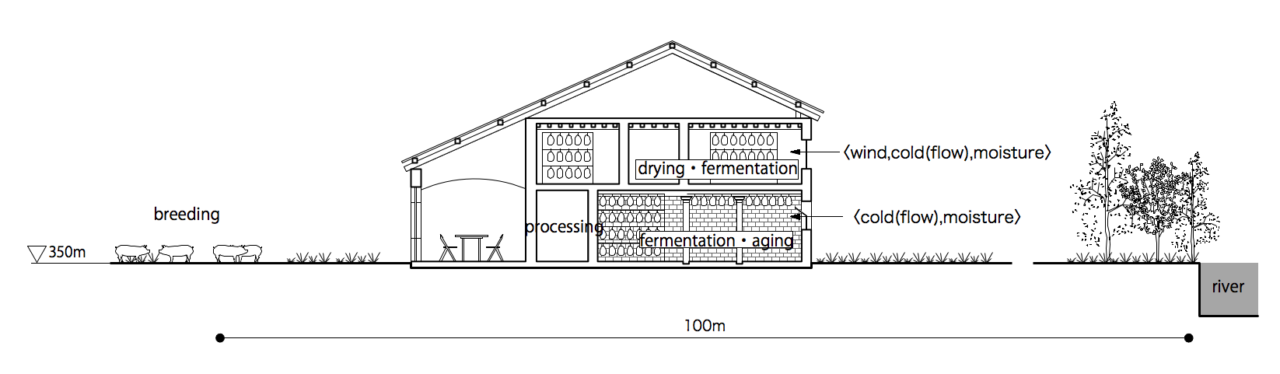

After salting and molding, the ham is dried and fermented. To promote drying, the room for drying is located on the second floor. The room has a French casement window with a window screen, and is left open. During this drying and fermentation process, meats other than Culatello are also hung in the same way. Alfredo continues to stick to natural drying, while a growing number of producers shorten the process of curing meat using refrigeration technology.

-

With the window left open, wind containing moisture from the Po River blows into the room

Alfredo explained the production process: “the production of Culatello takes place only between the November 1 and the end of January of the following year. If the ham is dried and fermented in the cold, we can complete the process without rotting the meat. In addition, another important reason for this period is that during this part of the year, wind blowing off the Po River contains a large amount of water vapor. By taking in moist wind during the drying and fermentation process, the meat can cure slowly. At the same time, drying the meat in a room with a high humidity level allows mold to form along the surface of the meat—this mold gives the Culatello its rich and deep flavor.”

-

Alfredo showing me the white mold while explaining about the relationship with the wind

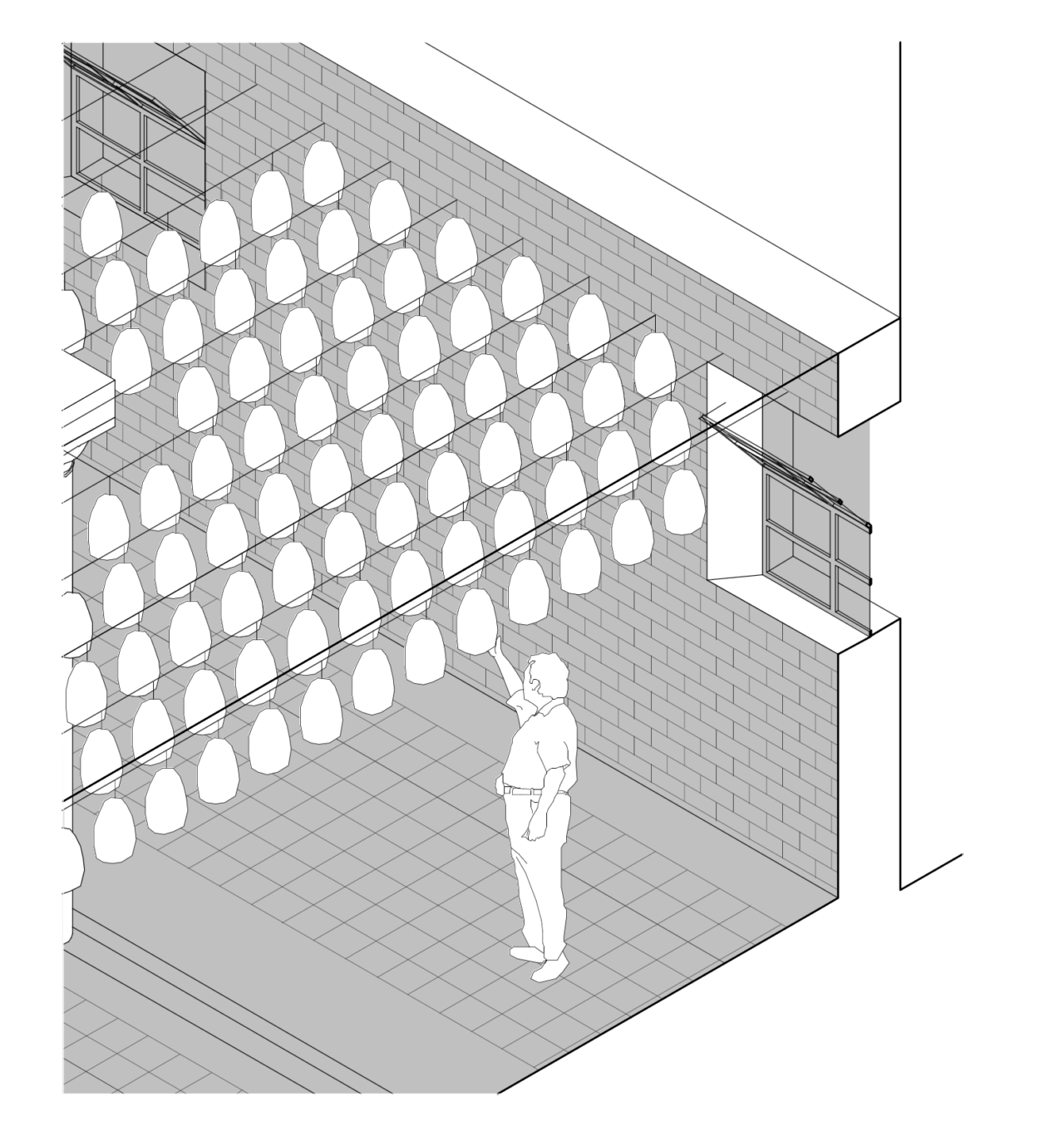

When the mold has grown sufficiently, the Culatello is moved to the first floor, and the process of fermentation and aging finally starts. In this room, hopper windows are situated along the upper half of the wall, near where the Culatello is hung. In the first six months of the eighteen-month aging period, the Culatello is hung near the ceiling where air with a high humidity gathers, allowing for moisture-laden wind to be taken in and facilitating the fermentation process. Over the next twelve months, the Culatello is then hung in rows above and below each other, as can be seen on the left side of the photo. This rotation between top and bottom is repeated over a fixed interval.

-

The fermentation and aging room is finished with brick walls, with hopper windows placed in the upper half of the wall

-

"Antica Corte," another production facility run by Massimo Spigaroli. This facility also has brick walls, with a French casement window.

When we look at the hygrometer in the fermentation/aging room, it is displayed at 90%, which shows that it is considerably high in humidity. The room’s brick walls are left unfinished, using the bricks’ porousness to help keep the humidity in the room high.

Thus, after a long period of fermentation and aging, the Culatello is finally completed. Culatello can be purchased as a single bundle, or with the mold and bladder, which serves as an outer skin, removed.

-

Culatello for sale

-

Pictures in the Culatello shop

When I looked at the walls of the shop selling Culatello, there were pictures of villagers eating Culatello. They hold the Culatello up, first enjoying the color and scent much as you would wine. Then they eat it, with their faces pointed up. Apparently, this is the most enjoyable way to enjoy the color, smell and taste of Culatello. When compared with other dry-cured hams, Culatello is characterized by the sweetness of the meat. When in the mouth, it is moist and the meat’s sweetness spreads mildly.

Process of Culatello production in Zibello village

-

Isometric view of the fermentation and aging room

-

Site cross section of Culatello production in Zibello village

The production of dry-cured ham Culatello in Zibello village takes place between November and January, utilizing moisture that occurs only during that time period. First, during the drying and fermentation process, the meat is moved to the well-ventilated second floor, to promote the curing of the meat. Wind and moisture are taken in from the French casement window. During the fermentation and aging process, the meat is hung from the ceiling of a room on the first floor, and moisture is taken in from the hopper window in the upper half of the wall, and from the porous bricks left unfinished.

Tomoki Shoda

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1990. Since his father transferred to many counties, he had lived in many places such as France, Indonesia, China and Belgium. Researched about traditional workshops in Japan for “WindowScape3 -working window” in Yoshiharu Tsukamoto Laboratory at the Tokyo Institute of Technology from 2014 to 2015. Studied abroad in Politecnico di Milano from 2016 to 2017. Researched about Italian Traditional food registered by Slow Food from the perspective of architecture. Graduated master course in Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2017. Researched Japanese Traditional food production as Slow Food Nippon researcher from 2017 to 2018. He has been in Takenaka corporation design team from 2018 to present.