Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Kibber, India : The Hidden Hole (part 2)

15 Oct 2018

It was cold in the morning so high above sea level.

But when I walked out to the third-floor terrace at my inn, I found it surprisingly warm. Yes, the temperature was low, but it nearly felt hot standing there under the sun. In fact, so much sunlight poured down on me that it practically hurt. I recalled all the Tibetans with their noses and the tops of their cheeks sunburned black, faces that told of lives lived high above sea level, close to the sun. When I looked out at the terraces where Darchogs (the five-colored flags of Tibetan Buddhism) flew, I could see many scenes of life in the village of Kibber.

-

The third-floor terrace of an inn

First, I saw a device that used sunlight to warm water. Water heated by the sun was then kept in a tank for use when bathing. It provided fairly hot water, and required no money for gas. This technology that turns the piercing sunlight into pleasantly warm water had already spread throughout the village.

I also saw lots of grass on top of roofs, which must have been hay used as feed for livestock. In this village where livestock such as cows and sheep grazed all around, the grass around the edges of the terraces of every home made for a slightly unique sight. This must have also acted to prevent people from falling from their terraces, and to keep dirt and mud from flowing away along walls when it rains. With all of the strong sunlight, these are quick, excellent spots for drying. The hay saved up for winter nearly overflowed, and some of it had been stuffed inside the buildings.

-

Hay stuffed in buildings

Not only that, the stove used in the living room on the bottom floor (that dries and burns livestock dung) peeked its head out from the roof. Seeing this made me realize that this terrace was an extremely important part of the home, acting as a space that gathers energy, such as that from the sun, before then emitting it. There was an indoor space on the third floor as well. It was a room for prayer, containing a home shrine and many figures of Buddha.

-

A room with a home shrine inside

Any two-story homes I visited in the Tibetan region of China contained rooms with home shrines at their top floor, just as this home did. Perhaps I am looking too much into it, but considering that it is the closest part of the home to the sun, this could have something to do with a religious kind of energy as well.

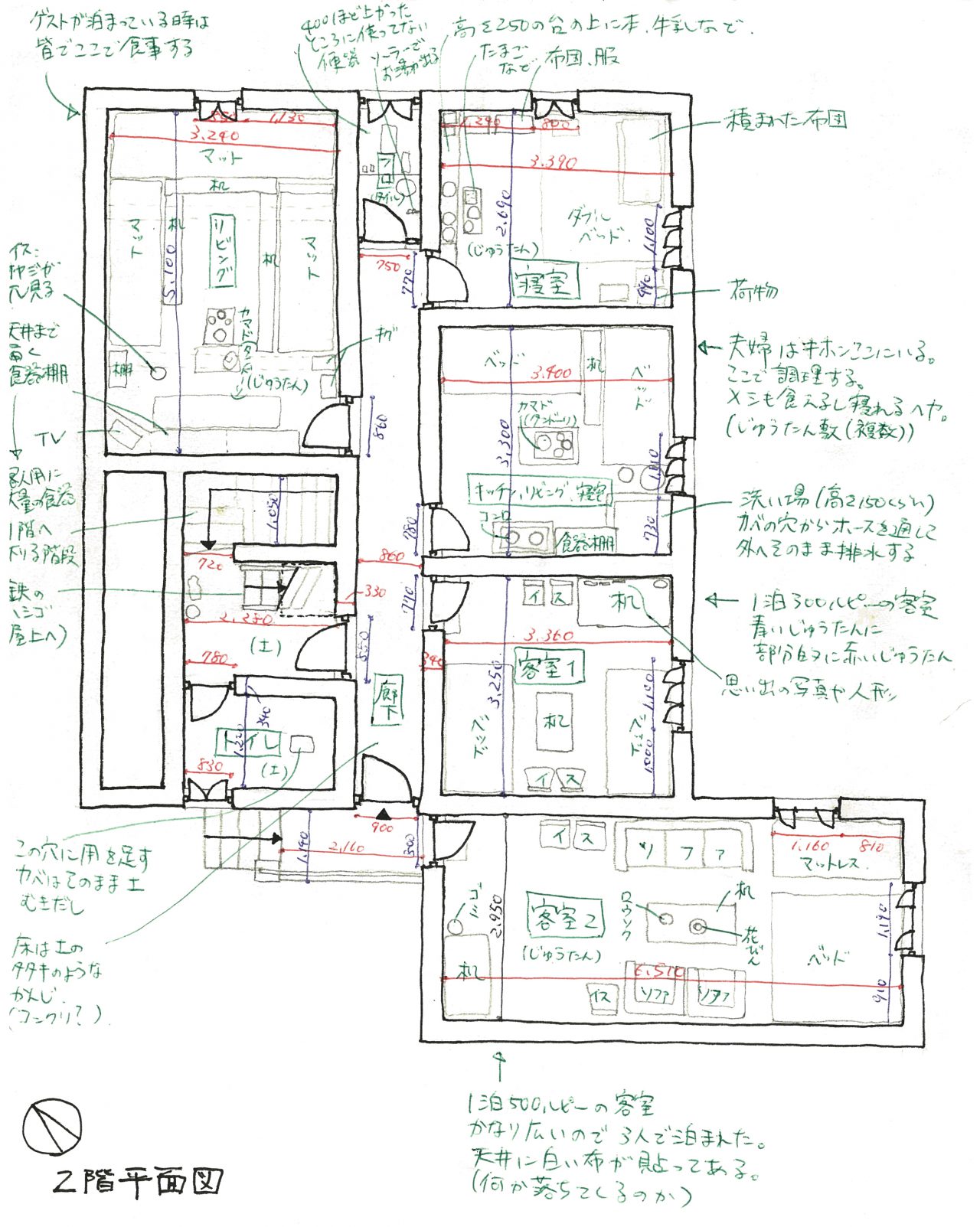

As the master of the home and his wife were not around, I occasionally sipped on hot tea as I pleased and took my time observing the inside of the house. As I drew diagrams of the second floor, its primary living space, as well as the third floor, where the terrace was located, I noticed an odd empty space in the second floor.

-

Floor plan of the second floor (accessible from outside stairs)

Once I began performing actual measurements, I realized for the first time that at the bottom-left of the floor plan for the second floor, to the side of the stairs and the room containing the toilet, appeared to be a space about 4 x 1 meters in size. There were no windows when I looked at it from the outside, nor could you enter from the inside. Still, there should have been a kind of hole right there.

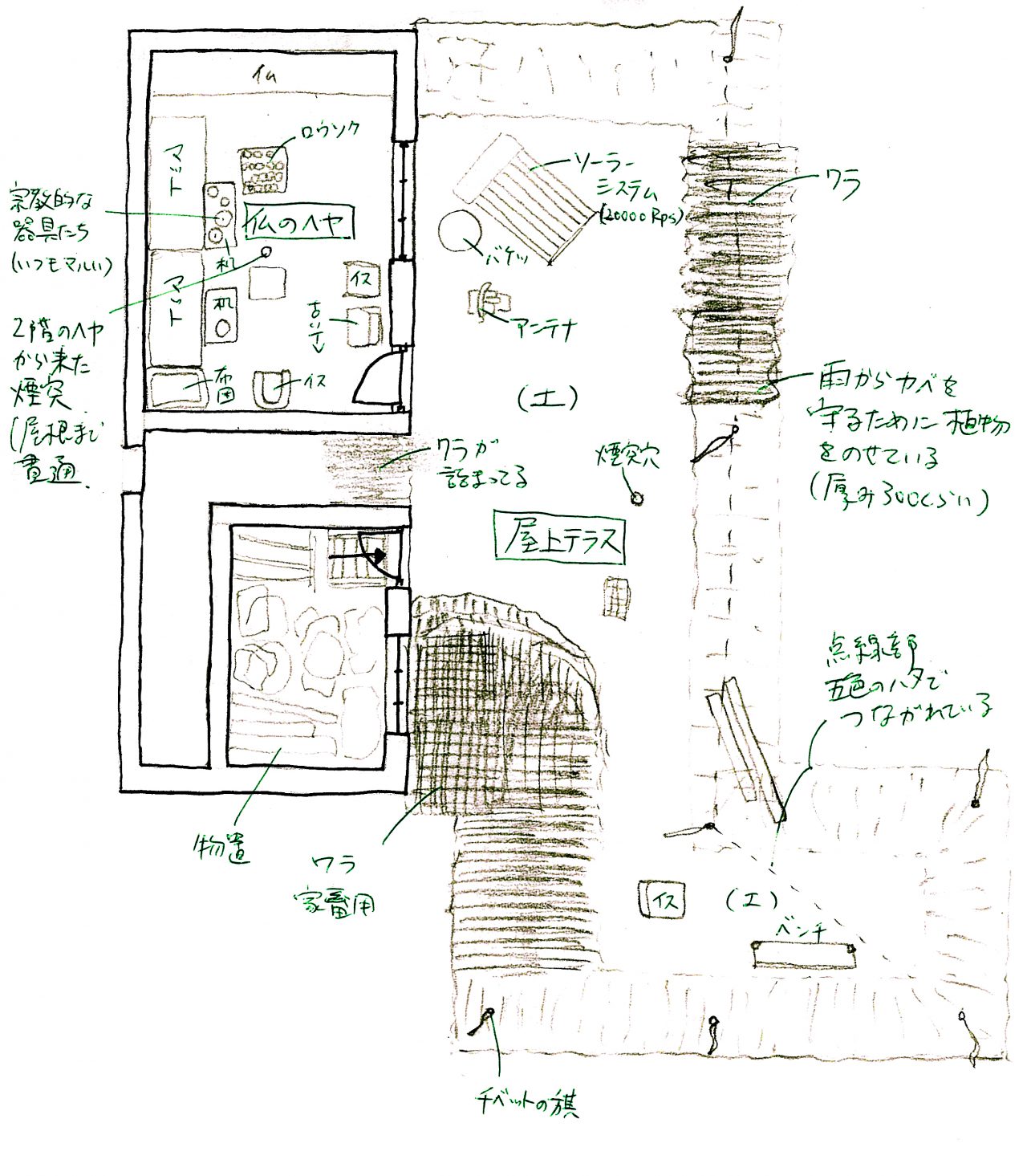

When I looked around the third floor, I noticed a space that was about the size of the second-floor “hole” ahead of an area stuffed with grass. However, the grass was stuffed so tight that I wasn’t able to look inside of the room.

-

Floor plan of the third floor

Once the master had returned that night, I asked him about this hole. According to him, there was grass stuffed in it. Not only that, it was stuffed from the first floor up to the third. The grass stuffed in the third floor must have made it down to the first floor where the livestock shed was located by way of this hole.

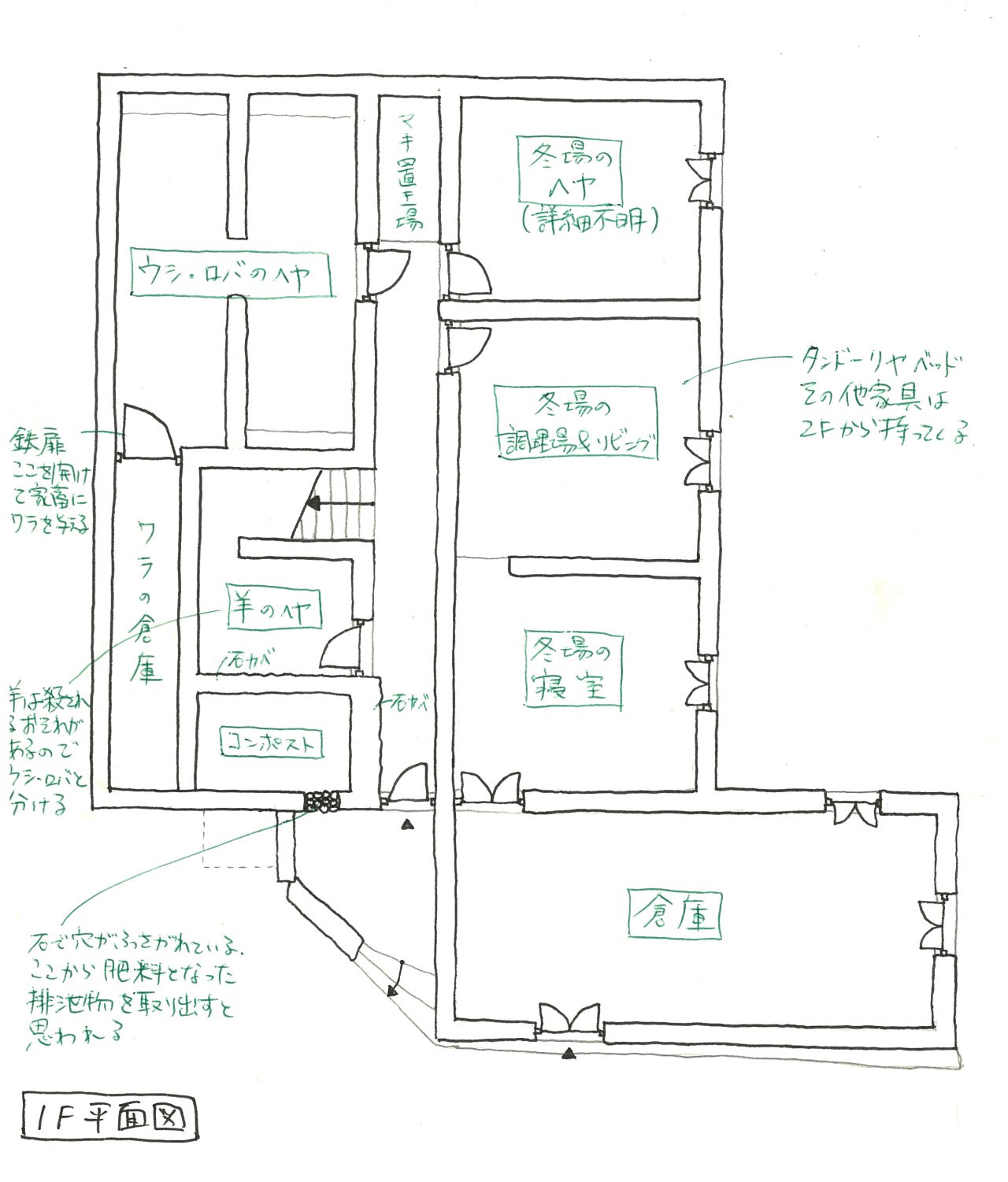

The next morning, I decided to take a look at the first floor, which I had yet to measure. It seemed to be used as a living space during the cold winters, and also as a shed for livestock. Dirt was exposed on the walls as I climbed down the stairs from the second floor, and the area felt like a dim storehouse. The livestock were out, as they grazed during the day. When I took a look at their room, I finally understood what I had been told the day before.

-

Hole exit connected to the third floor

In short, the grass stuffed from the third floor fell down to the first by way of the hole, allowing for three layers’ worth of height in storage. The exit was shut off by a door, and opening it would allow the livestock to be fed hay directly. The area also acted as a closely manageable storehouse that meant people would not have to bring hay down to the first floor each day themselves.

-

Floor plan for the first floor

(The vertically narrow area to the bottom-left is the “hidden hole”)

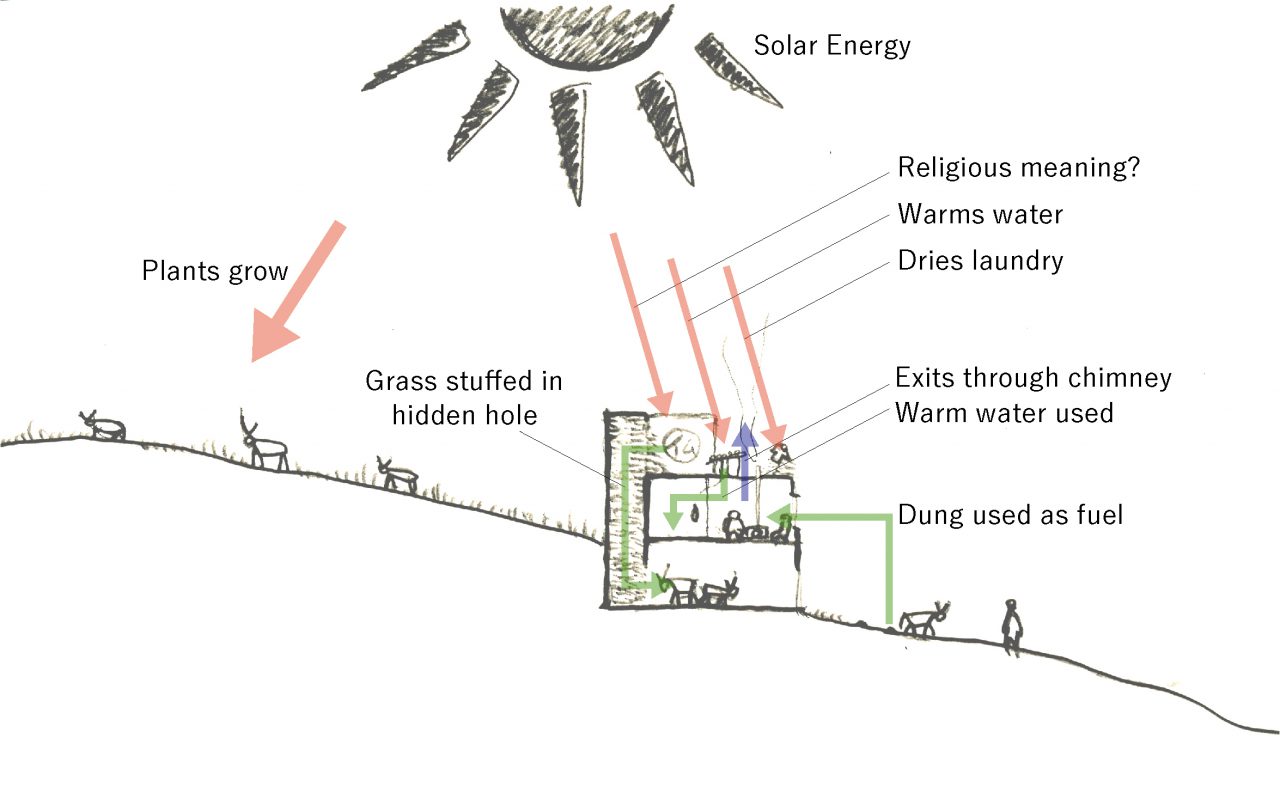

The top of this building in this settlement used the sun’s massive energy to create warm water and dry clothes. Additionally, this area closest to the sun contained a room with important religious meaning. Similarly, plants that had used the sun’s energy to grow before being taken there by humans could be stuffed into a “hole” to reach livestock on the first floor. The livestock provided nourishment for the lives of the people, and their dung was burned for heat energy before leaving through the chimney sticking out of the terrace… It was as if this building was breathing dynamically as one with its humans and animals.

-

Diagram of a “breathing” Kibber house

Having discovered this close relationship between the sun, a dwelling, its people, and their livestock that I never could have imagined from the outside made me feel like I was able to get a small glimpse at how the people in this settlement truly lived. The white Tibetan homes with their square windows that looked simple at first glance had clearly been designed with care as a part of this close relationship, as seen by this “hidden hole.”

Once evening came in the village, the sheep kept by each home returned. They knew that they too were a part of the cycle of life here.

-

Sheep waiting for their master after returning in the evening

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.