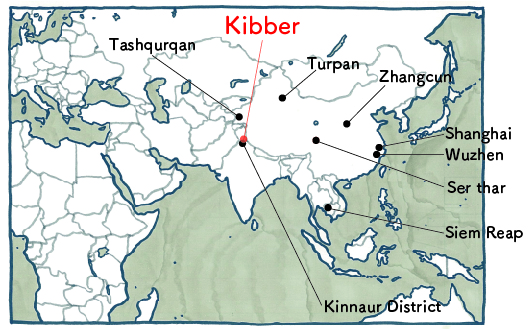

Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Kibber, India : The Hidden Hole (part 1)

25 Jul 2018

Climbing even higher past Kinnaur district in North India, I passed the treeline to find an outstretched land of nothing but brown, rocky mountains. I transferred between local busses while having the strange thought that I probably wouldn’t be able to make it back alive were I to be let off here all alone.

After traveling through the Tibet Autonomous Region in China, I had traveled southward to Southeast Asia, only to enter India, climb mountains, and meet Tibetans again. They live in a place that is breathtakingly beautiful. It’s hard not to be charmed. This area, known as the Spiti region, was part of the route by which Buddhism was introduced from India, which is why some Tibetan people continue to live quiet lives there. Tibetan people (used here to refer to adherents of Tibetan Buddhism) dot the Himalayan mountain range, created by the collision of the Indo-Australian Plate with the Eurasian Plate. In other words, they live focused around the location where the Earth’s energy is most visible, going beyond any concept of nations or states.

Many of their structures are built with unique identifiers that can be spotted with a single glance. They appear as white boxes evenly dotted by small windows. They just barely feel inhabited by people thanks to the colors and decorations around the windows that contrast with their white surfaces. When I spotted their gathering of white boxes from afar, it made me feel the poignancy of people gathering to live together. Perhaps they may have shared my imagined feelings about being let off a bus all alone.

-

Looking at the Tibetan people’s settlement from afar, separated by a cliff. The white walls are easy to spot even after it begins to get dark.

The village of Key in the Spiti region is home to Key Gompa, built about a thousand years ago (Gompa means temple). As Tibetan temples are built with the same characteristics as their homes, the structure sticking to the peak of a cliff looked like a tight clump of gathered homes. It was hard to even tell which housed monks and which were built for worship.

-

Key Gompa. It is built in a way that makes it seem as though it’s tracing the rising shape of the land.

In this installment, I’d like to focus in particular on the village of Kibber in the Spiti region. It’s a small village, with only a gompa and a few dozen homes. Kibber is a village 4,200 meters above sea level, and it seems it was once quietly famous among travelers as “the highest village in the world.”

I arrived in the village on a bus I shared with Indian and Colombian youths I met on the way, then found my inn. Only a few inns were located in this village that saw close to no travelers at all, so we were able to stay in the house of an older couple that advertised it as a homestay inn. It was a typical Tibetan home for the area, and it was inexpensive and pleasant (aside from the guaranteed power outages each day). In an even bigger stroke of luck, the master of the inn allowed me to survey his home as I lived in it.

Homes in Kibber are generally two or three stories tall, and their walls are made from rammed earth (their lower sections are built from stonework due to snow). Rammed earth construction is a method that has been used since ancient times even in countries such as China and Japan, and it involves simply packing earth together to build a wall one level at a time. According to the master of the inn, they are not weak to the area’s frequent earthquakes, either. When they shatter one home to pieces, those pieces can be used as materials to create the next home. I saw the buildings before my eyes and wondered just how old the homes whose materials they used could have been.

-

The village of Kibber. The white homes are built along the valley facing southward.

I spent my first two days going to see Key Gompa and looking around the village.

Windows that looked rectangular from afar actually had dark and somewhat oddly shaped borders around them when seen up close. The master of the inn said that they were meant to be shaped like the horns of a god.

-

The exterior wall of my inn

In addition to air and light, it must have been thought that the holes in these rectangular homes standing in the barren wilderness could let in invisible spiritual presences or something unwanted. I felt like I could understand the need for these “charms” in the form of decorations.

-

An old-looking home. Its lower portion is built from stonework, while the upper portion is a rammed earth wall. (A horizontal line can be seen after each level.)

Just walking around the village had left me incredibly tired. At this elevation, simply climbing slopes was enough to make me feel out of breath. I could personally feel how much of a waste of energy it would be to move quickly or speak in a loud voice. No wonder I had felt this need to live peacefully in such an elevated community.

This tranquility made it feel as though I had been confronted with a world that I could never enter despite existing in the same age as us. I wanted to see the deeper parts of this world that were not visible upon a first, quick glance. I saw the other travelers off as they departed for the next town and decided to stay behind alone.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.