Series The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Architectural Ethnography, Part B

07 Jun 2018

To commemorate the opening of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia (May 26th-November 25th, 2018), the Window Research Institute caught up with architect Momoyo Kaijima for an interview. Kaijima is a co-founder of Atelier Bow-Wow and teaches Architectural Behaviorology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ). While working as an architect at the van guard of her field, she has brought a uniquely architecture-focused bent to her extensive body of urban research. We wanted to ask about her ecological, architectural understanding of how we live.

In this second half, we look at real research examples from Kaijima’s work investigating Window Behaviorology at ETHZ, which shed light on her research approach and the architectural theory underpinning her practice.

Can you talk a little about the Studio Bow-Wow ETHZ, where you and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto teach?

It’s a studio we set up in August, 2017 at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ). ETZH has a studio system, so students move around between studios to hone different drafting skills and study the architectural philosophies that interest them. Studio Bow-Wow ETHZ focuses on Architectural Behaviorology, and this year students spent their first semester researching the Machiya (townhouse) windows of Kanazawa.

Does anything change about how your students approach architecture, when you narrow your lecture topic down to something as specific as windows?

My students are all fascinated by windows, and they came to Japan during the first semester to learn about how different sliding windows open horizontally, how the panes of doors and windows can be easily swapped out. It serves to give them a sense of the vocabulary of Japanese architecture and traditional Machiya, but windows are something you have to actually live with and use in order to fully understand. Namely, the idea of shōji and fusuma (latticed sliding partitions with paper panes) goes against everything they’ve learned about security, soundproofing, and insulation. If you grew up in Japan, you’ve seen them in movies, or you may have even lived in an older home with these sorts of partitions, so you know about keeping your voice down, closing doors gently, and how to use windows—how to behave in an older building. But for students coming from abroad, this experiential barrier creates a rather daunting gap in understanding.

But I feel like this research exercise lends my students valuable understanding of how design elements can be employed to great effect outside of the context that they’ve created and conserved for them, and how their own context is a product of particular environmental factors.

What sort of research do you have in store for the future, at the Studio?

Well, this semester I’m lecturing on the theme of Window Behaviorology in Switzerland. Switzerland encompasses the Swiss Alps, and can be broken down into German-speaking, Romansch-speaking, Italian-speaking, and French speaking areas, and after hashing it out with the students, we decided to split up and conduct our research in separate groups for each of these areas.

The Alps, in particular, are this frigid, high-altitude region, the southern Lausanne area getting particularly good sunlight, while the snowbound La Chaux-de-Fonds is famous for its clockmakers. The canton of Ticino cuts a deep valley but opens toward the south, and its location on the South Alps make it relatively warm. The northern plateau known as Mittelland, on the other hand, is less mountainous than other areas, making it a rich agricultural region and a causeway connecting Austria with France and Germany—which is the reason some of the farming villages evolved into manufacturing hubs for textiles and the like.

So Switzerland has this stark diversity of regional climate and character, each area with their own distinct forms of industry, commercial and otherwise, and we’ve discovered that this diversity correlates to its windows. Switzerland may be a wealthy country now, before the war it was an impoverished region, covered in snow, with little arable land or agricultural diversity, and many of its citizens immigrated to France and other countries for work. When the first and second world wars broke out, these itinerant workers returned home with their earnings, and built homes in the architectural styles of the countries they’d lived in.

-

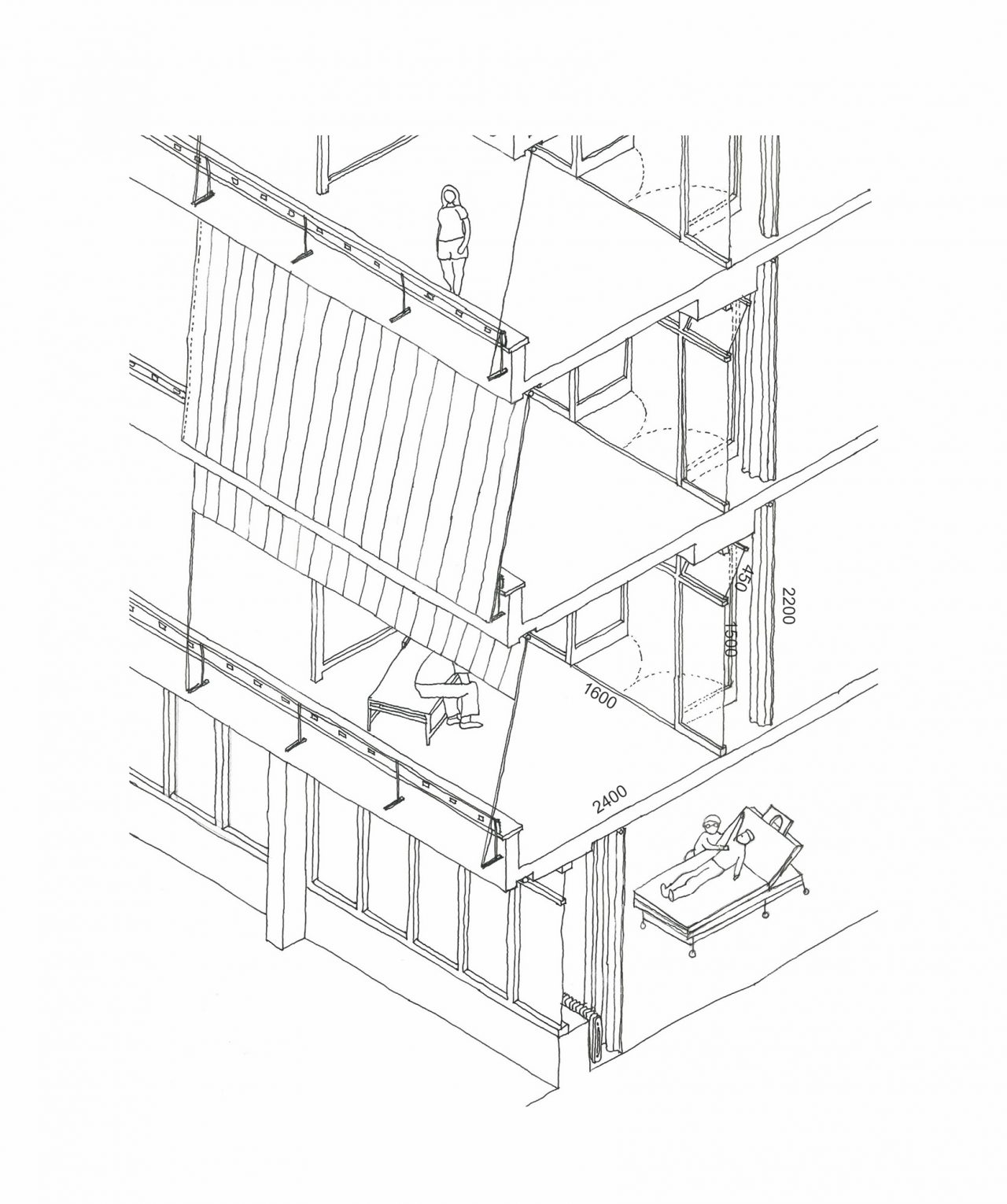

Berner Klinik (A Clinic in Crans-Montana)

Drawing of balcony windows with individual bed access

Image coutesy of Genta Ishimura

-

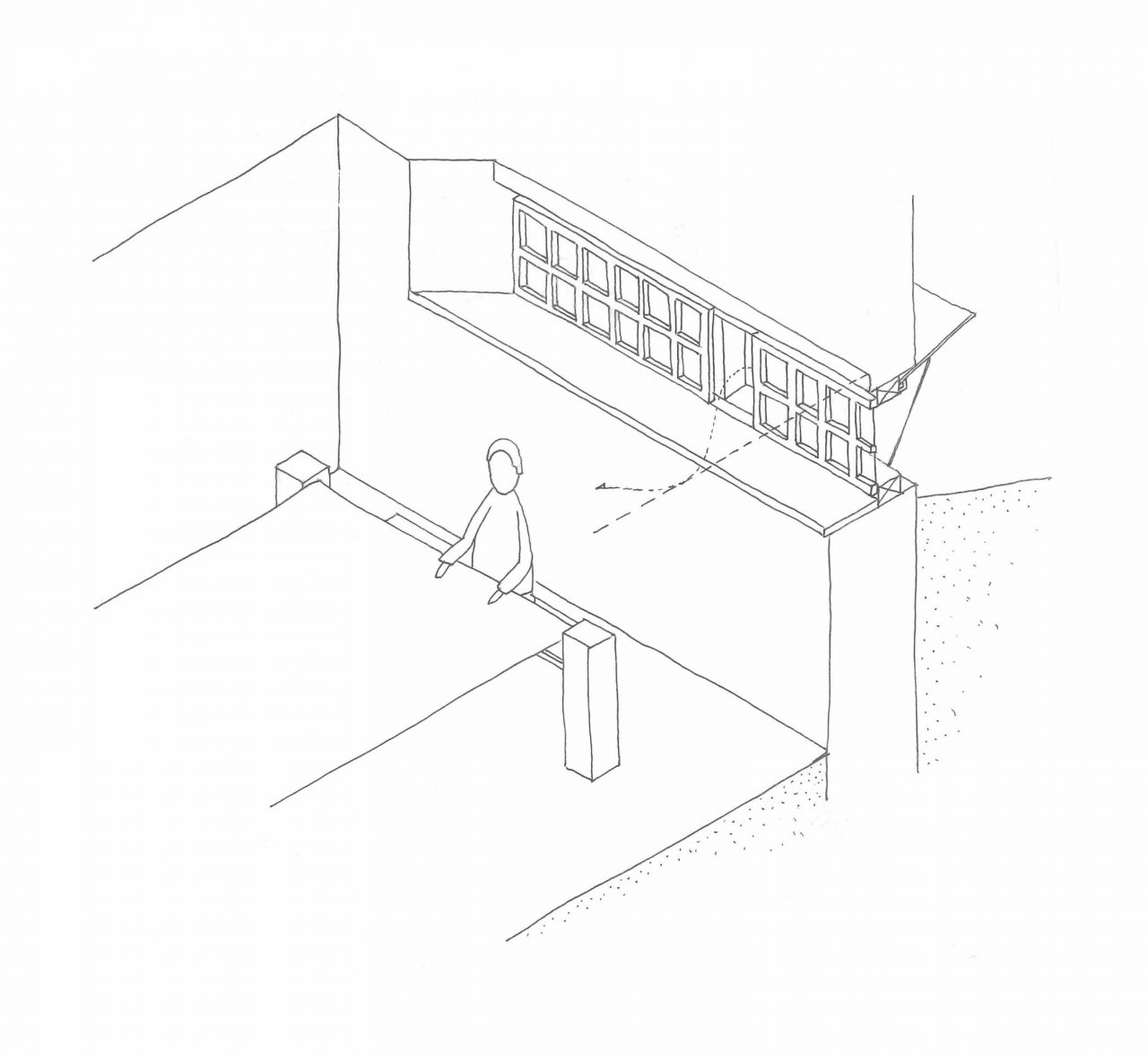

Exterior of Berner Klinik (A Clinic in Crans-Montana)

Image courtesy of Studio Bow-Wow ETHZ

-

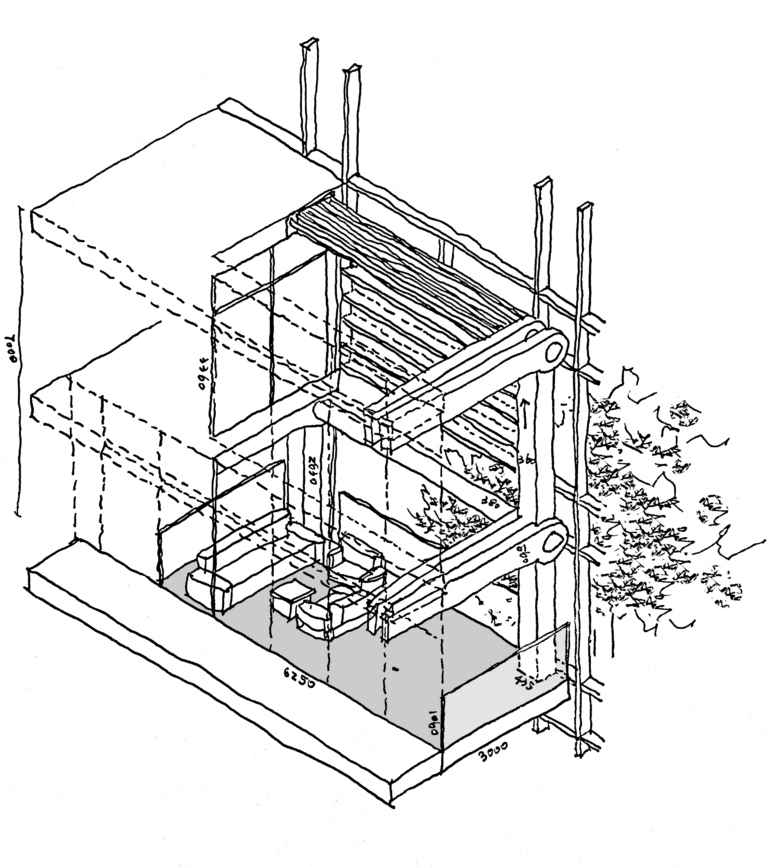

Private residence in the canton of Appenzell

Drawing of horizontal window with accompanying structural design and textile worker

Image courtesy of Lena Stamm

-

A housing typology (Appenzellerhaus) in Appenzell region

Horizontal window – an example of the form’s contemporary application

Image courtesy of Studio Bow-Wow ETHZ

For example, those families who migrated to France and returned wealthy integrated integrated French-style windows into their homes. Of course some of them still used distinctly Swiss windows, but it was these families that returned from abroad and built new houses who were responsible for developing many of the new Swiss forms of window. Some migrants from industrial areas, who returned from doing business abroad, even built entire homes in a foreign style. This new infusion of culture was given singular expression in windows.

Switzerland has a cold climate in the winter, and the Swiss were early adopters of the double-paned window. Installing double-paned windows is an expensive proposition, which made them something of a luxury item. The houses of the poor simply don’t have many windows. This is an entirely different from the Japanese sensibility. In Japan, the idea of a “window” originally comes from adding a partition to an already open space. Whereas in Europe, homes are made out of walls, and windows are decorations that one adds to the walls, if one can afford to do so.

Do you ever use the sort of sketches in this exhibit as an tool in your studio, as well?

Sure. I’m not opposed to working with digital tools or anything, but computers allow you to simply copy and paste your work. In doing so, you run the risk of losing your embodiment of the work, of treating is like your data. I feel like when you work by hand, you internalize the way that the water flows as you draw it, the way a surface might be off-balance, and all this helps you understand the climate, the details—all the warp and woof of a structure.

-

Roll up window in Zurich found and drawn by Kaijima’s student

Image courtesy of Zhe Dong

In conjunction with the biennale, we’re scheduled to host a workshop on drafting with students from ETHZ, the University of Tsukuba, and the University of Queensland. The goal is simply to show students the sorts of things that can be conveyed through the act of drawing.

The biennale begins on May 26th. What sort of goals have you set for the exhibit, and what do you hope people take away from it?

As a retrospective of past work, I think the exhibit will help us reframe our past projects in terms of the work we are undertaking now, and clarify which tasks deserves our attention, and which challenges need to be engaged with greater circumspection. Architectural Ethnography can help us do this by tweaking the way we look at the world—perhaps my greatest goal is simply to help people understand this. If I can help this kind of understanding spread, then I feel like I’ll be helping the world move in the right direction.

And of course I want it to be fun. We’ve made the exhibit as accessible as possible for visitors from all over the world, and my hope is that as many people see it, talk about it, critique it, and argue about it as possible.

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition

La Biennale di Venezia, 2018

Theme: FREESPACE

Directors: Yvonne Farrell, Shelley McNamara

Location: Giardini di Castello, Arsenale

Dates: May 26th – November 25th, 2018

Website: http://www.labiennale.org

The Japan Pavilion

Theme: Architectural Ethnography

Curator: Momoyo Kaijima with Laurent Stalder (Associate Professor of Architectural History, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Chief of the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture) and Iseki Yū (Curator, Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery)

Assistant Curator: Simona Ferarri, Tamotsu Ito, Andreas Kalpakci

Curation Team: ETHZ Studio Bow-Wow, Laurent Stalder (Associate Professor of Architectural History, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Chief of the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture), Iseki Yū (Curator, Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery)

Presented by: The Japan Foundation

Momoyo Kaijima

Born 1969, in Tokyo. In 1991, she graduated from Japan Women’s University, where she majored in Housing and Architecture. The following year, she founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto. In 1994, she received her masters degree from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and spent 1996-97 studying abroad at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ). In 2000 she left Tokyo Institute of Technology without finishing her PhD, and spent the next nine years as a lecturer at the University of Tsukuba. In 2009, she became an associate professor at Tsukuba, and received a RIBA International Fellowship in 2012. She has been a professor of Behavioral Architecture at ETHZ since 2017, and has taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (2003, 2016), ETHZ (2005-7), the Royal Danish Academy (2011-12), Rice University (2014-15), Delft University of Technology (2015-16), and Columbia University (2017). While designing residences, public architecture, and train station environs, Kaijima has continued conducting architecture-centered urban research like “Made in Tokyo” and “Pet Architecture.” She is the curator for the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia (2018).

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Thresholds between Coexistence and Architecture

25 Jun 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Interview with Tom Emerson, 6a architects

22 Apr 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Windows: Openings and devices

12 Dec 2018

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Liquid Light

12 Oct 2018