Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Floors and Floods: Siem Reap, Part 1

11 Jan 2018

Siem Reap is one of the cities in Cambodia, along with Angkor Wat, that is hopping with tourists who come to see the ancient ruins that lie there. After seeing some of the major spots in the ruins like many of the other travelers, I wondered what kind of homes the locals lived in nowadays, and borrowed a bike from my economically priced lodging to ride along the river. According to the calculations I had made earlier while studying a map, if I rode about an hour downstream I would arrive at the well-known Tonlé Sap lake.

Tonlé Sap is famous for being the largest lake in Cambodia, or one should say, the largest lake in Southeast Asia. Like a “moving” lake, during rainy season it can grow up to 9 times deeper and cover 6 times as much land as other times of the year. This fluctuation in the amount of water makes for healthy farming and fishing industries, but the surrounding villages are inundated with water during rainy season, so there are many residences built above the water or on high pillars.

As I rode toward the lake, I started to see houses built atop tall pillars. They were around 1 to 2 meters high and made of wood with corrugated sheets for roofs, but the brick and larger houses used concrete.

-

The closer I got to the lake, I began to see houses held up by tall pillars

The pillar supported houses became taller and taller. In time, the hill upon which some ruins called Phnom Krom are situated became visible to my right. Perhaps people have lived there since ancient times, I mused. Further along, I left my bicycle at a small village and began to walk.

-

The village with houses held up by tall pillars

There was a road going straight through the village, and in the earth below, which was a few meters lower, homes were standing atop pillars all lined up, one next to the other. I assumed this arrangement was planned out, and the land that the homes stood upon was the natural level of the earth, while the road was built up above that level as a preventative measure for floods.

In order to enter the area with the homes along the road one must cross a simple wooden bridge that had been installed there. There were children playing in front of the entrance to a shop. The pillars that held up the buildings were slender, and stuck rather simply into the earth.

-

Crossing from the village road to get home

I wondered just how tall the pillars were, so I descended down below from the steep slope at the side of the road. Looking up from there, I could tell that these pillars were taller than those I had seen on the way over, and were generally around 4 meters tall. The severity of flooding that occurs was reflected in the height of the pillars.

-

Surrounded on all sides by houses being held up by 4 meter tall pillars

I felt an odd peace of mind surrounded by these pillar-supported homes. I got the sense that with a whole 4 meters to use, the space below the homes wasn’t what we would consider just the space below the floor, but rather it was a separate usable space of its own. People put up hammocks, built walls of plants, and even built floors to eat on in this at times underwater space, in which plastic bottles and bags were strewn about, some short grass grew, and cows strutted about freely. They were like rooms that went away during rainy season.

-

The area beneath a building being used as a room, with household items strewn about and hammocks hanging

The homes were built with extremely inexpensive materials. The frames were made from slim wooden boards and the walls and roofs were thin zinc sheets that were hammered into place rather simply. Focusing in on the windows, I noticed that most did not open outward or to the side, but were only apertures with zinc sheets thrown over them and held up by a stick. They seemed like they were only eaves, but they were really very rationally designed, as simply by supporting the sheet at the top, one could easily block rain from coming indoors and allow air to flow inside at the same time.

-

The windows that kept opening one after another

The windows in the area were flying open one after another as if they were alive. They were endearing, appearing much like eyelids to me. I got on my bike and road further on toward the lake, imagining the windows closing all at once before an oncoming squall.

Ryuki Taguma

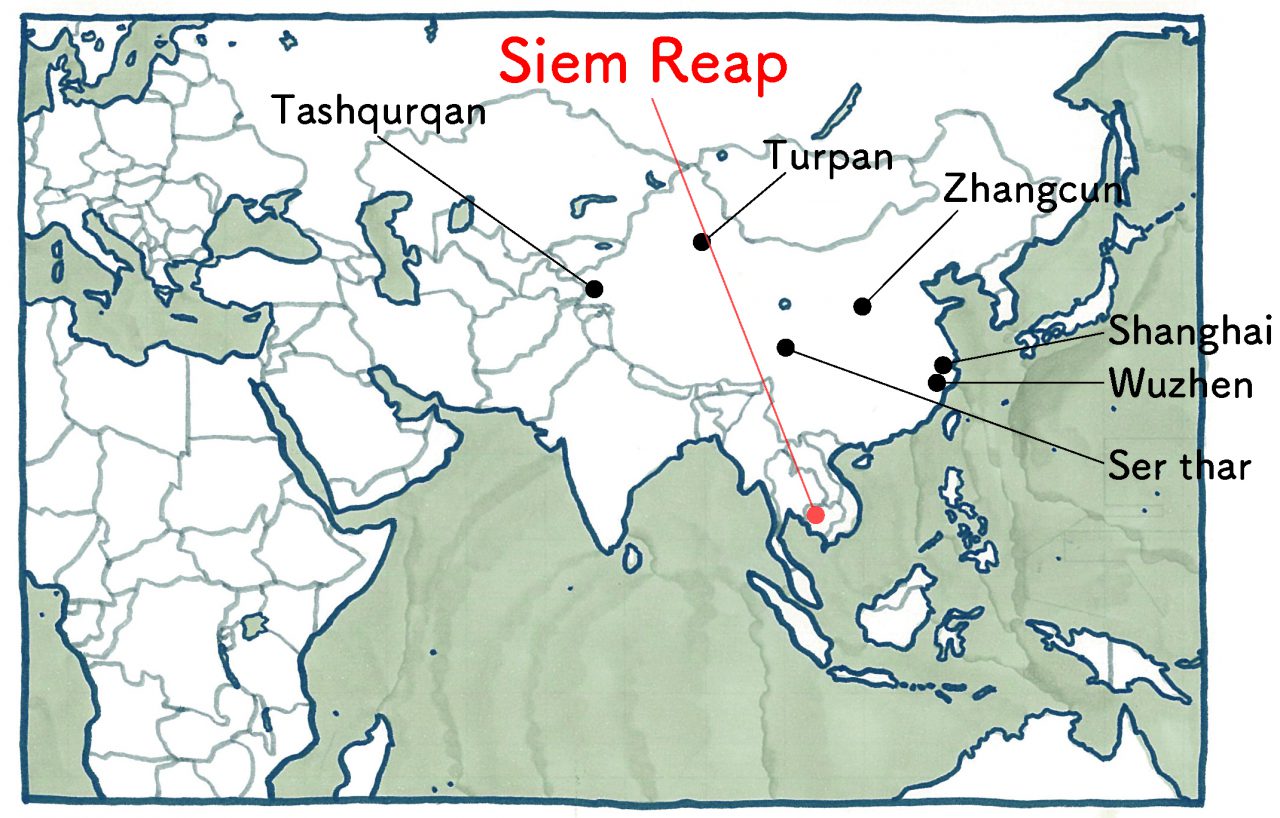

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.