Series La Biennale di Venezia 19th International Architecture Exhibition (2025)

The Fit of a Dialogue: Living and Generating Within the In-Between

21 Oct 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Exhibitions

The 19th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale (2025) is being held from May 20 to November 23, 2025. The Japan Pavilion exhibition IN-BETWEEN was curated by Jun Aoki (architect) and Tamayo Iemura and features work by Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura and SUNAKI (Toshikatsu Kiuchi and Taichi Sunayama). How was the exhibition’s theme, “in-between”, manifested within the pavilion? Architect Takahiro Ohmura, who produced the video installation together with artist Asako Fujikura, explains.

0

A myriad of sounds reaches my ears from within the gallery.

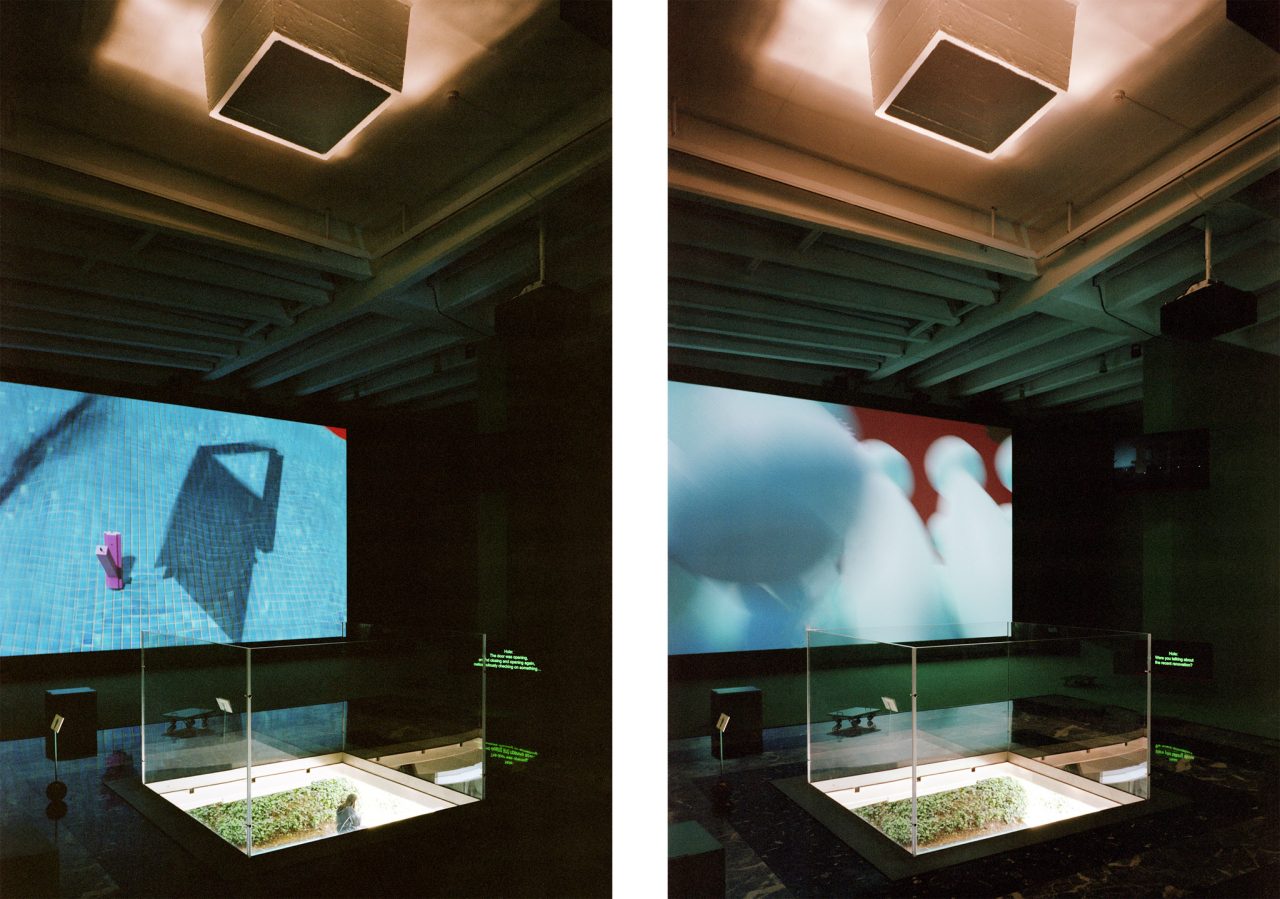

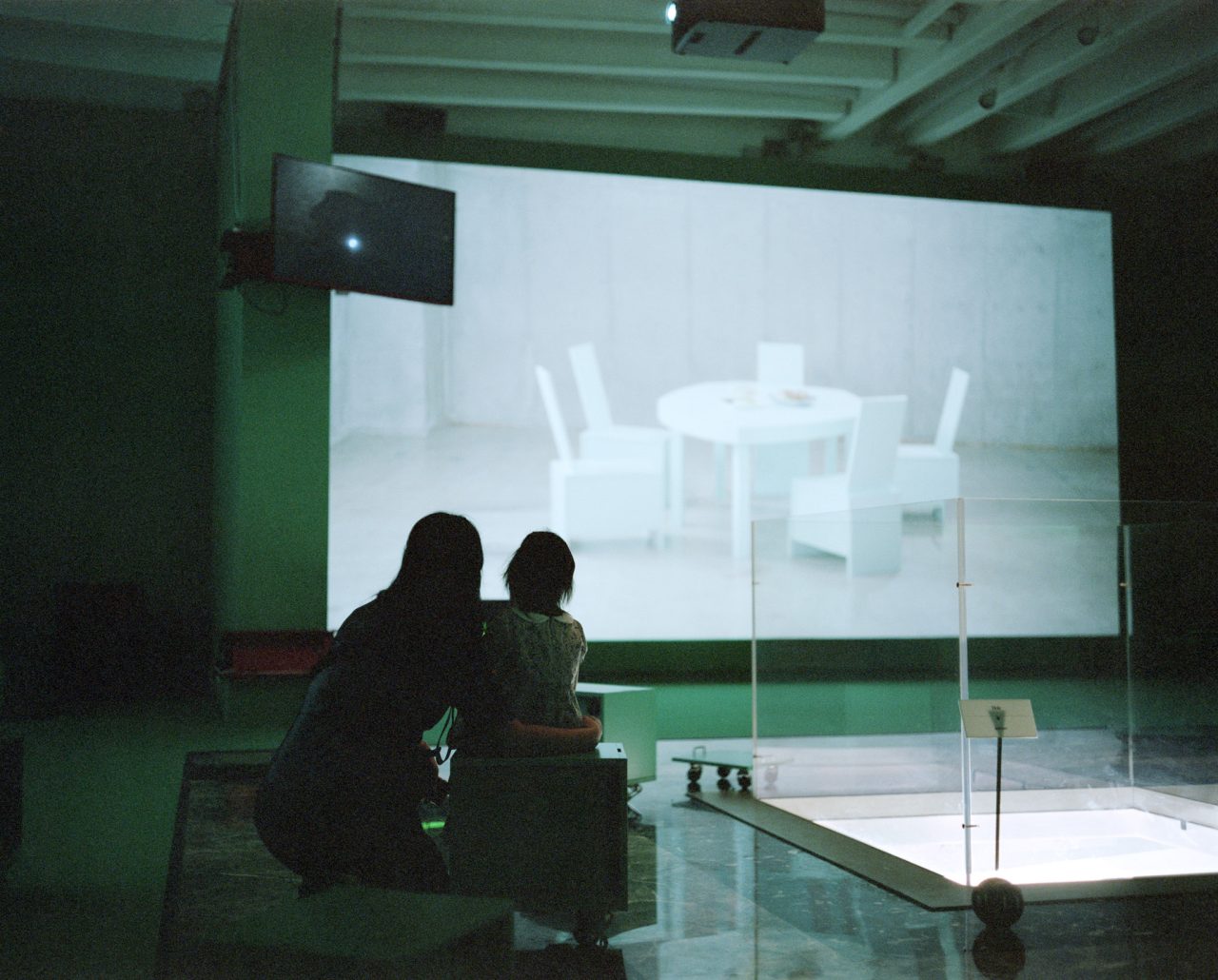

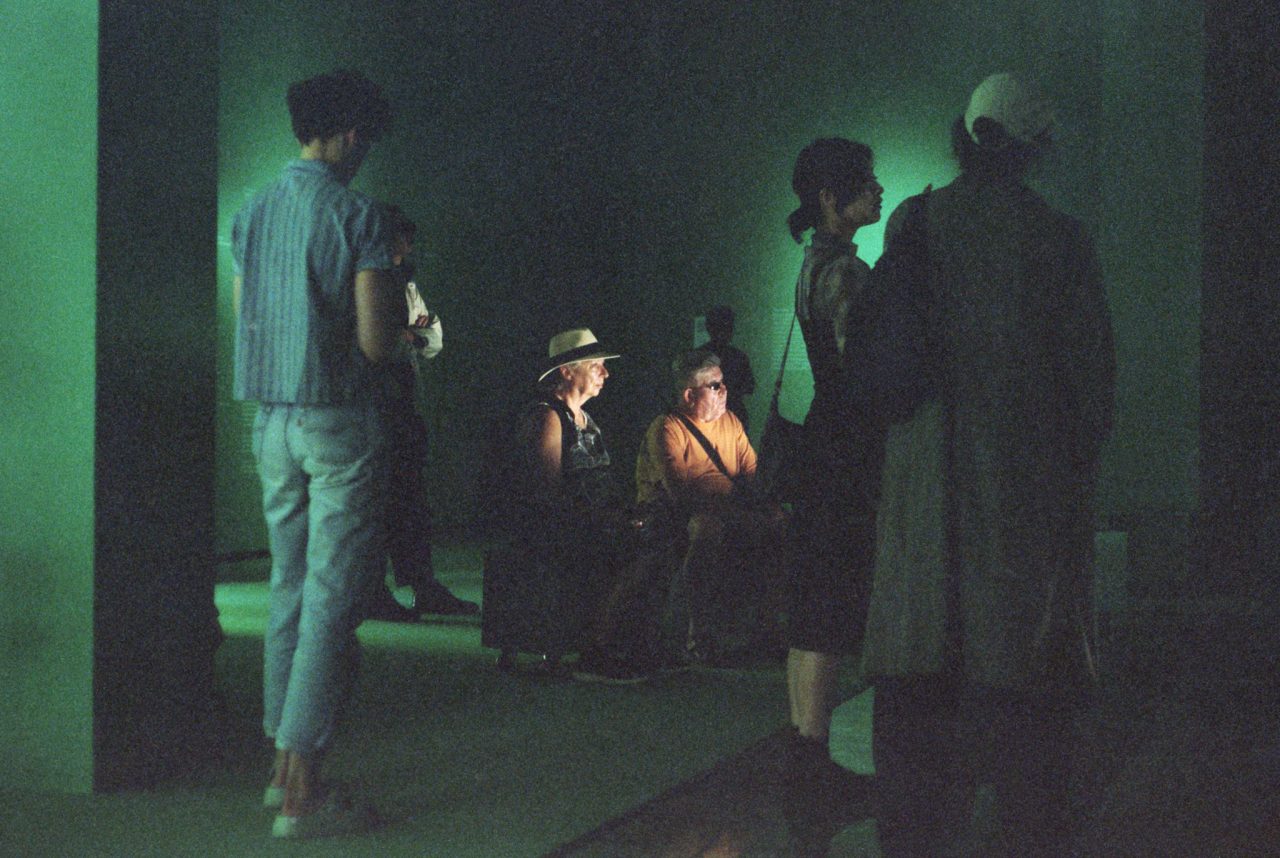

Passing beneath the stepped canopy structure—the object, known as the Pensilina, is unique to the Japan Pavilion, which was built to the plans of Takamasa Yosizaka in 1956—I enter the gallery, where the floors and walls are covered in carpeting and paint of nearly matching shades of green. The white ceiling, too, appears tinged with green from the reflected light. The green tone permeates the entire darkened space. After reading the greeting text laid out on the wall to the left-hand side of the entrance, I turn my body, letting a pair of large screens fill my field of vision. Two arm-mounted displays float between them, and in the floor there gapes a hole, around which are scattered what could be chair parts.

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

I hear a voice from the front right-hand side, speaking in English.

To use the human language is to use the human body. I was created by actions of human labor. Stairs are made by human knees and hips…1

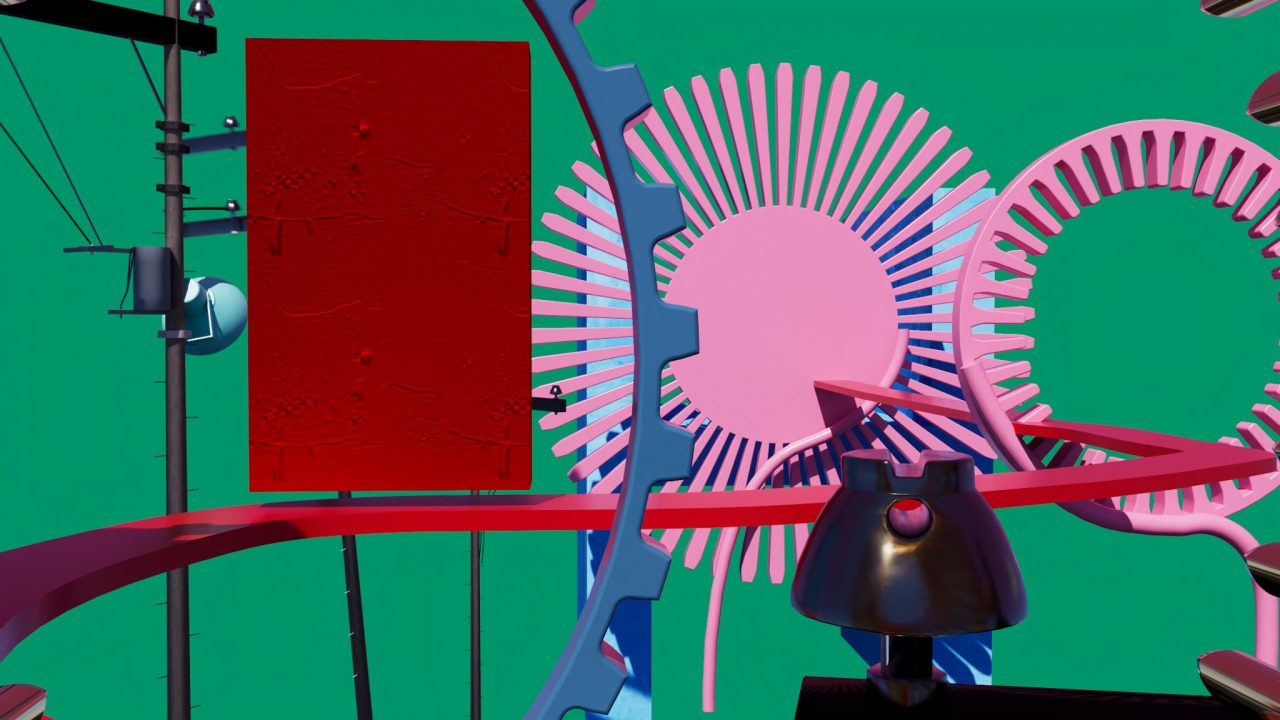

The right screen shows a live-action video of people portioning out food. The left screen shows a 3D CGI video of a red-colored tube-frame structure, casting its shadow onto a reddish desert landscape. The glossy red tubes quiver up and down and emit a hammering sound, seemingly in response to the spoken dialogue. The mounted display presents a dark, desolate field within which objects sporadically appear, illuminated by a spotlight.

Another voice chimes in from the direction of the entrance.

Sometimes, they climb on me. Do you remember when those people attached something to the top of the box? They were all dressed the same. It made the birds angry when they flew overhead. There aren’t usually humans there, so the surprise may have given them a heart attack.2

A pair of femurs, rendered in metallic pink, ascend a set of steps on the left screen. On the right screen, a woman clasps her hands, ready to begin on the food laid out before her.

More voices follow, overlapping:

The birds who come to eat my fruits made similar complaints. It doesn’t seem like much, but for them, it must be quite a shock.3

Food travels through the body, slowly, slowly rebuilding it… Where does the soul of the food go? Could it be… into that orange, spiky thing, that awaits with outstretched arms…? That thing, I fear that thing! Sometimes it brushes past me, but I have not the slightest clue what is inside… It is terrifying!!!4

The left screen transitions to a scene of a sandy expanse beneath an elevated expressway, where pink, lustrous, bristly objects sway as if to twist their bodies. Before I can process what they are, the screen cuts to a highly synthetic architectural space composed of repeating concrete and glass elements.

Renovations don’t change me much. But it seems like the humans that use us often think I’m troublesome! Am I necessary for humans or am I not? I just don’t understand.5

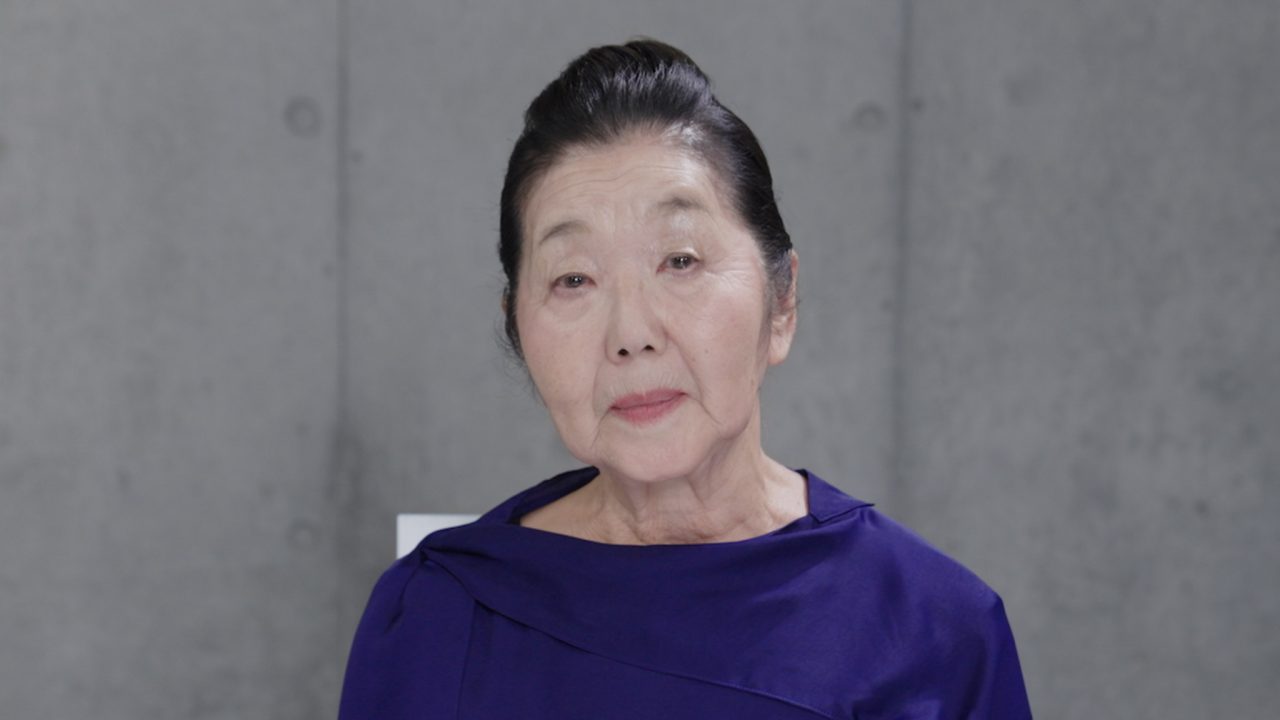

The right screen closes in on a woman’s face. Gazing straight back at me, she speaks in Japanese:

Take a proper look. It’s open. It’s magnificent.6

The human quietly interjects in the dialogue between the non-humans.

1

This is a text about IN-BETWEEN, the exhibition presented at the Japan Pavilion for the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale (2025), written from my perspective as one of the exhibitors (Takahiro Ohmura). Asako Fujikura (artist) and I were reasonable for the exhibit inside the pavilion’s gallery, where we put together an installation consisting of synchronized videos running continuously on a 17-minute loop.

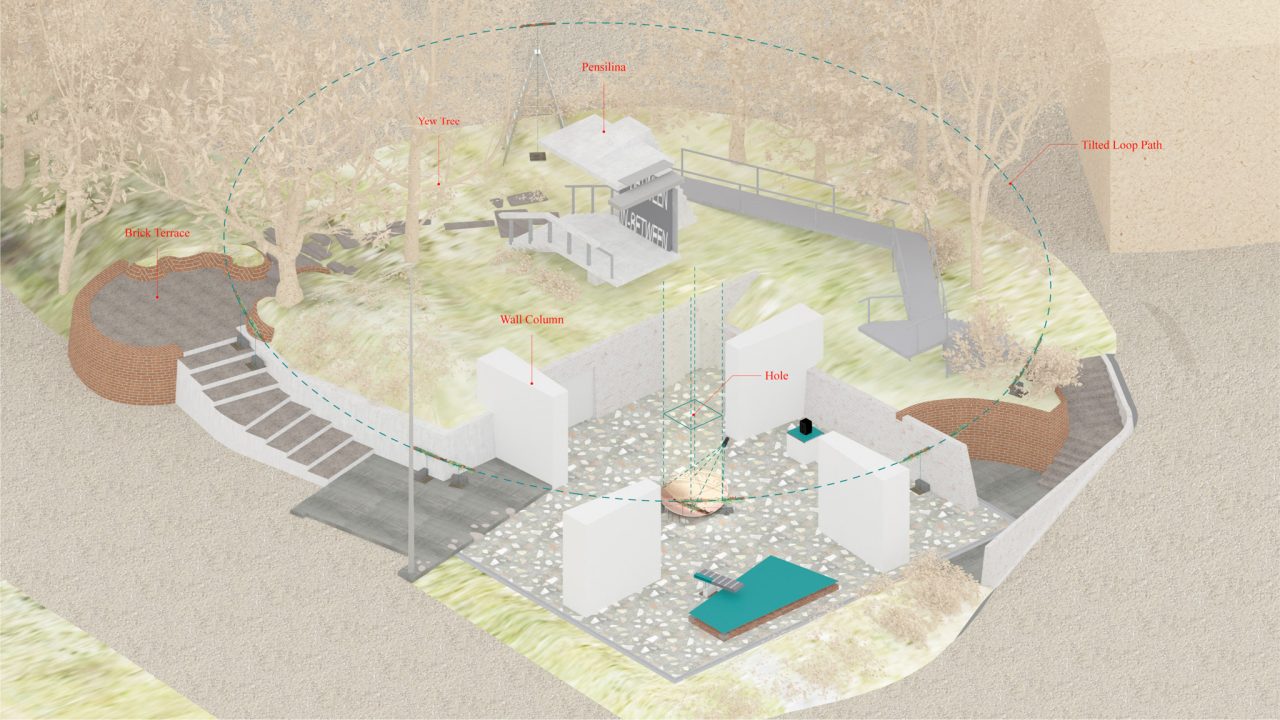

What we created is an “architectural play” of sorts, in which architectural elements are cast as actors (characters). Set in a near future where humans and non-humans are capable of communicating using natural language, its plot follows a dialogue about renovating the Japan Pavilion, held among various features of the pavilion—the Hole, Wall Column, Outer Wall, Pensilina, Brick Terrace, Tilted Loop Path, and Yew Tree—each with their own personality. All things perceivable—whether a building element, tree, brick paving, air, or circulation path—are treated alike as objects forming part of the pavilion’s architecture. The exhibition space is filled with the voices of these material and immaterial actors.

-

Image: SUNAKI Inc.

The Hole expresses doubts about whether it is essential to the Japan Pavilion, and the other actors respond. Through their dialogue, in which symbolic interpretations of the Hole are avoided, they come up with a re-reading of the pavilion as a work of rotational architecture that ties the four Wall Columns (piers) to the Tilted Loop Path (an imaginary path circling the pavilion site). Ultimately, the Hole reaffirms its raison d’être as the eye of the storm—an axis of rotation connecting the pavilion’s interior to its outsides.

The Japan Pavilion is composed of four rotated T-shaped wall-column units joined in windmill-like fashion. By examining the building closely, one can see that the hole at its center was not created by deliberately puncturing the floor and roof; rather, it is a residual void, born incidentally from the rotational motion of the structural units. The scenario of the dialogue can thus be seen as a kind of theatrical tutorial for revealing and conveying the pavilion’s underlying rotational logic.

-

Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Object Video, 2025.

©︎ Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura

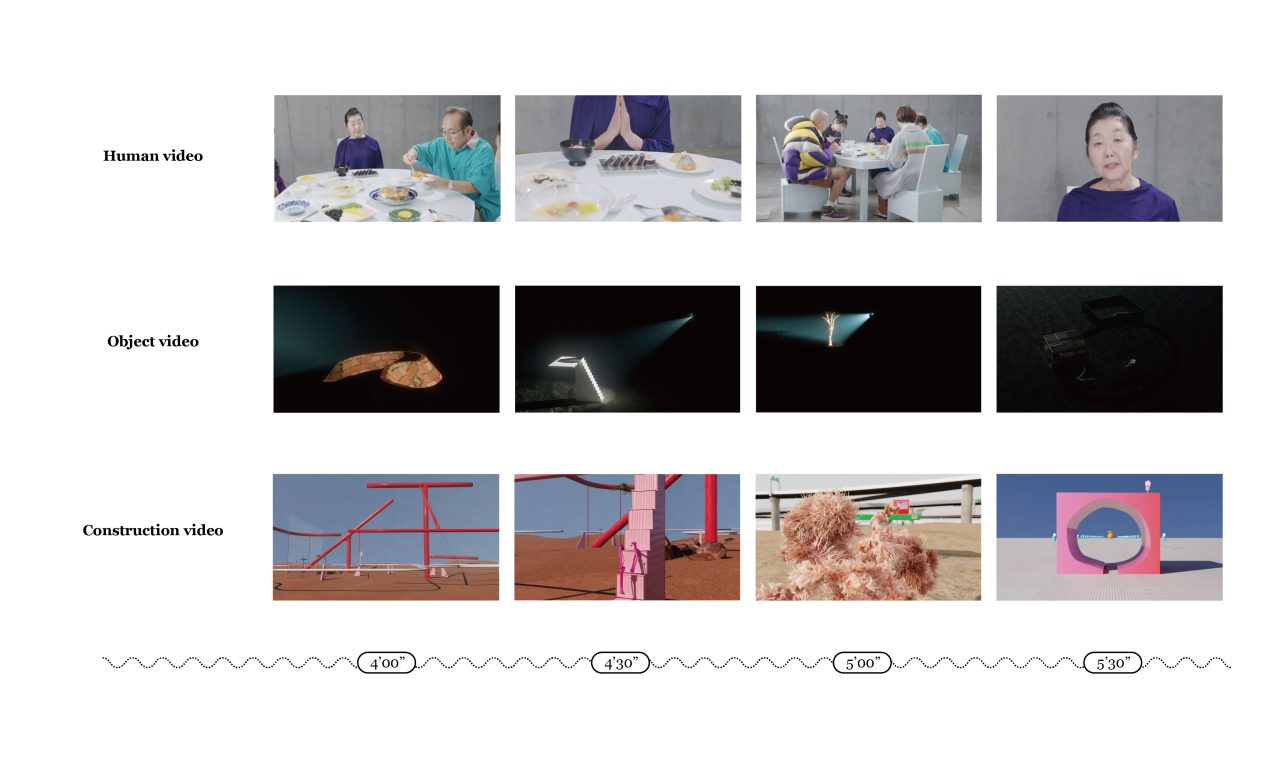

The voice-filled gallery features an arrangement of four videos. The two large main screens face each other obliquely. One is the Human Video (HV), a live-action video depicting five people seated around a dining table. The other is the Construction Video (CV), a 3D CGI video depicting fictional landscapes constructed based on the dialogue. Installed between these screens are two smaller arm-mounted monitors extending out from a wall column. One displays subtitles, while the other shows the object currently speaking (Object Video, or OV).

-

The HV, CV, and OV run simultaneously on a 17-minute loop.

The Hole, which serves as the protagonist within the scenario, forms a vertical void piercing through the center of the pavilion (sky ⇄ skylight ⇄ floor hole ⇄ piloti space). Being a mass of air, it loses its identity as a hole the instant an attempt is made to represent it two dimensionally. For this reason, the Hole does not appear in the OV. Instead, when the Hole speaks, the ceiling is illuminated by light projected upward through it from the piloti space.

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

The dialogue that unfolds here is not intended to convey a coherent narrative or clear message. Rather, it serves as a means of establishing a condition in which videos, sounds, words, bodies, and architecture exist in a state of constant mutual interference—a neutral point, or in-between—within the gallery. This was what Fujikura and I were primarily interested in achieving. The focus of the viewers’s attention continually slips off to the side—from the videos to the floor, from the hole to the outside, toward the scattered sources of the sounds, and back to the videos again. The act of experiencing the work repositions the viewer’s body between the fictional video experience and the actual tangible experience, altering the very way in which humans encounter the architecture.

2

Fujikura and I became involved with the Japan Pavilion exhibition for the Venice Biennale in March 2024. It was Taichi Sunayama who first contacted us. He and Toshikatsu Kiuchi work together as SUNAKI, a rare creative unit that is not only well-versed in digital technologies but also has experience with the Biennale. Jun Aoki, who had been invited to participate in the competition to produce the Japan Pavilion exhibition, reached out to SUNAKI immediately upon deciding to explore the theme of “Architecture and AI”.

Around then, Fujikura and I were working on a manuscript for a special issue of the online journal Kenchiku Tōron [“Architectural Debate”], guest edited by Sunayama.7 Back then (and still today), global physical distribution had become markedly unstable, impacted by war and related disruptions. Notably, Houthi attacks on vessels in the Red Sea had intensified, and shipments from Japan to Italy via the Suez Canal faced serious delays and risks. In light of these circumstances, Aoki sought to assemble exhibits built entirely from digital data files, eliminating the need to transport physical works. He must have seen us as a good fit for this plan, as we had been producing work that traverses the boundary between architecture and video.

Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Fixing Garden, 2022–.

A project that aims to simultaneously create a fictional landscape and restore real spaces through the act of garden-making. Various things gathered and produced through the artists’ research are compiled within a 3D CGI space, creating a virtual garden-like landscape used to inform the renovation and design of a real vacant house and its garden and to generate the details of the thresholds—i.e., windows—between the building and garden.

We had already solidified the general concept of having AI-enabled architectural elements attempt their own renovation by engaging in a dialogue with humans at the time of the competition. From the start, our interest lay in the architectural question of how AI technology might change our living environments (and our relationship with them), rather than the technical question of how an autonomous non-human intelligence might be realized. What we sought to explore was a disposition for embracing irreconcilability—the question of how we might engage with an “other” whose very existence transcends our imagination.

We ultimately participated in the invited competition as a three-unit team—the curators (Aoki and Tamayo Iemura), SUNAKI, and ourselves—and successfully made it through to the end. In the summer, we all traveled together to Venice for a site visit. Our impression of the hole changed the most after seeing the Japan Pavilion in person. Although we had already cast the Hole as a character in the scenario we prepared for the competition, encountering it directly revealed many new insights. In particular, we found the view looking down through it into the piloti space to feel strangely unreal; the view jumps out at you with a vividness that almost makes you think that it is actually the other side that is fictional.

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

It was from there that Fujikura and I began discussing whether we should make the Hole the protagonist. We recognized that repositioning the Hole at the center of the scenario would inevitably change the meaning of the renovation, as it could no longer involve plugging or reshaping the Hole (such renovations would result in its erasure). We decided instead that the renovation should be about allowing the Hole to function effectively as a hole—that is, to leave it intact and have it facilitate the passage of various binary oppositions (inside/outside, reality/fiction, artificial/natural). The Hole thus would become a window. Achieving this condition, or perception, through altering the way in which people access the architecture became one of our goals when developing the exhibition’s content.

3

After returning from the site visit, Aoki sent us a storyboard sketch of the dialogue. While the Hole was not yet the protagonist at that point, he had imaginatively identified rotation as the fundamental principle of the Japan Pavilion and introduced the idea of having the Tilted Loop Path be an actor. From there, I set about writing the first draft of the script. It took me two months to complete, however, as I ran into the difficult problem of how to prevent the fictional scenario of non-human entities speaking from feeling contrived.8

Tangentially, neither Fujikura nor I made use of generative AI to any significant extent when creating the final products of the installation, whether for video production or for scriptwriting. Why we refrained from relying on LLMs (large language models) to autogenerate the dialogue certainly warrants explanation. Current generative AI models are undoubtedly capable of drawing from their immense corpora of human-written language data to statistically recreate speech patterns that might evoke the character traits of the Outer Wall, for instance. However, it is fundamentally impossible for them to autonomously construct the Outer Wall’s ontologically grounded perception and worldview. When speaking specifically about generative AI (particularly LLMs), as opposed to artificial intelligence in a broad sense, such models decisively lack the bodily sense of reality that resides within language—the perceptual experiences grounded in one’s own body, such as the sense of gravity, resistance, or the irreversible flow of time. This was precisely why we thought that, in order to avoid falling into the “trap of anthropomorphism”, which amounts to nothing more than superficial linguistic mimicry, and to conceive the body of an other that is not human, the most careful and sincere approach would be to have the human viewer use their own body as a foothold to mentally construct the perceptual structure of an external other.

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

To help us establish the fiction of “giving voice to architecture” by treating architectural elements as subjects with perceptual structures fundamentally different from humans, we wrote a set of rules, or constraints (devising these rules and a system for their implementation was what required two months for script development). We essentially designed a structural framework that would allow us to systematically establish and develop the premise of non-humans communicating in natural language without having to contrive the objects’ “independent wills”, while simultaneously translating the dialogue into another medium—video. The rules are as follows:

(1) Dialogue-Driven Space Construction

A core rule. The role of the subject who probes the dialogic space and speaks is continually passed on to human or object characters appearing in the dialogue. The work is structured such that the objects and situations appearing in the dialogue are fed back via the Construction Camera—i.e., visualized on screen—making (by rule) any depicted object a potential speaker. As the agency of speech passes from one character to another, a “space” comes to be perceived—i.e., constructed—post facto.

(2) Actualization

A core rule. All things said in the dialogue are actualized within the reality of the scenario—they do not remain in the realm of metaphor or mental imagery. Every utterance must be processed and incorporated into the scenario as physical reality (e.g., saying “let’s get rid of the walls” would cause the walls to actually disappear).

(3) Subjective Exaggeration

A device for developing the dialogue. This provides a way of articulating the unique perspective of each object. Objects speak about physical laws and natural phenomena (e.g., the permeation of rainwater or the degradation of building materials) as they perceive them, sometimes making exaggerated (or fictional) claims based on leaps of logic.

(4) Inversion

A device for developing the dialogue. The role or significance of a character may be inverted through the dialogue (e.g., the static Hole is recast as a dynamic axis of rotation), sparking new plot developments. Additionally, spatial inversion axes (e.g., you/I, back/front, left/right, etc.), pre-planned in the script, trigger the Construction Camera operations outlined in Rules 1 and 2.

(5) Non-Visual Sensory Triggering

A device for developing the dialogue. Utterances concerning non-visual sensations (e.g., sound, wind, moisture, texture, etc.) reveal differences in the speakers’ physicalities. This provides a way not only to depict each object’s unique spatiotemporal perception but also to set up subsequent lines and events.

(6) Uncertainty-Induced Stoppage

When a speaker expresses uncertainty (e.g., “I don’t know”, “I can’t see”, “I’m not sure”, “I can’t hear”, etc.), the dialogue-driven space construction process comes to a temporary halt, marking an opportunity for spatial differentiation. The space must be continually differentiated and laid out as it is being constructed so that the dialogue arrives at the plot resolution—where the Hole facilitates the passage of various binary oppositions.

These six rules do not function independently; they are designed as an interdependent system. Forming the foundation are Rules 1 and 2, both derived directly from our original vision for the video pieces at the time of the competition: translating words into a landscape. The resulting dialogue script served as a collection of prompts, or instructions, that preceded the production of the videos. The HV, CV, and OV can thus be seen as three distinct iterations produced from a single shared set of instructions.

4

What is intrinsic to living beings but not to artificial intelligence? Two things came to our minds: first, a body, and second, the irreversible flow of time. The act of eating encapsulates both succinctly. With each bite, the contents of one’s plate diminishes, and what has been eaten cannot be restored. This observation became the basis for the HV, which depicts a group of five men and women sitting around a dining table (the table forms a distorted pentagon, assembled from fragments of the Tilted Loop Path). The characters encircling the table, in somewhat awkward proximity, are of various ages and genders, but do not appear to be a family. The aim of this piece was to present a cross-section of the human existence as a contrast to the non-humans.9

The casting was key. Before writing the specific lines, Fujikura and I carefully discussed which character should speak. We meticulously developed each character’s details, including not only their age and gender but even their place of origin, personal history, political leanings, mannerisms when eating, speech cadence, and the ways they direct their gazes toward their neighbors. Then, rather than having actors play these characters, we choose to seek out real people who approximated the scripted personae. We looked for individuals capable of effortlessly embodying the fictional roles while maintaining their own subjectivity—people who would not need to act.

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

Our basic plan was for the cast members to share a meal together in front of the cameras as themselves.10 That said, the entire situation of speaking prescribed lines surrounded by camera, lighting, and sound equipment was obviously abnormal for them, since they were not professional actors. They had no training in reproducing instructed movements. However, precisely because of this, the cameras were able to capture their shifty eyes and awkward limb movements. We sought to structurally set up a scene that was neither documentary nor fiction but something in between. A central subject of this video was the characters’ rigid bodies, produced by the subtle nuance of not acting out lines and yet remaining physically tense.

5

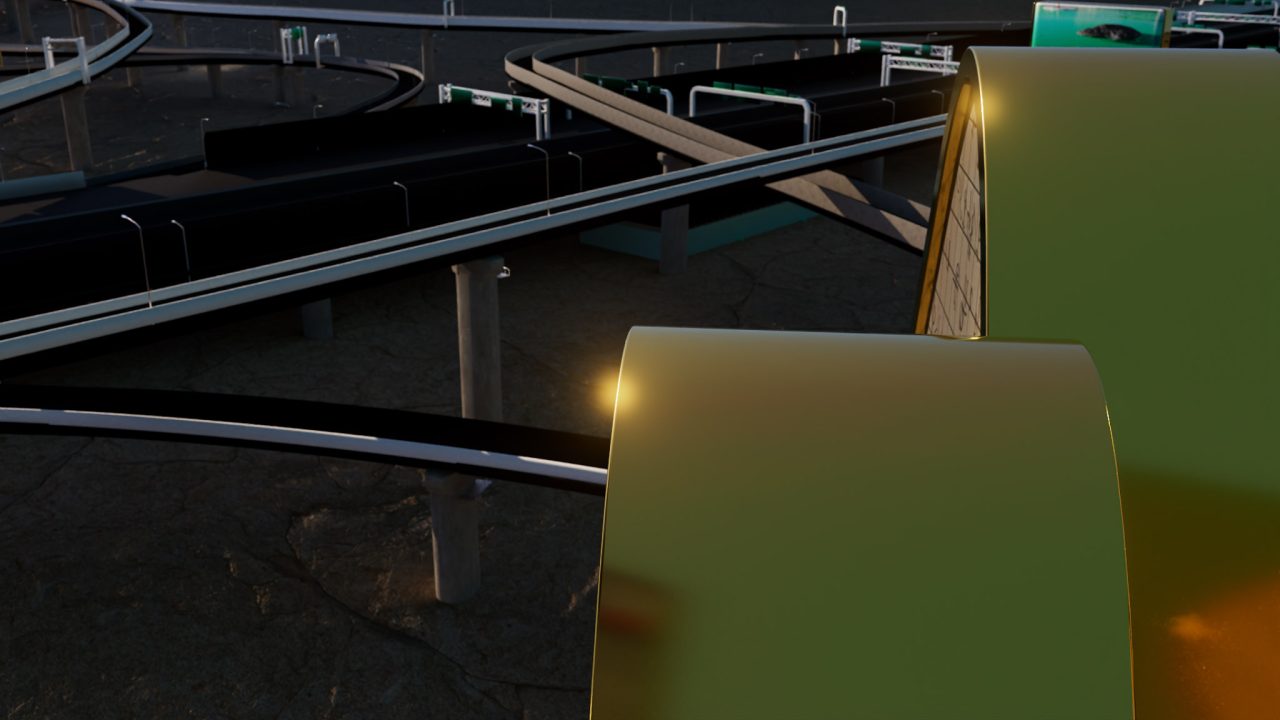

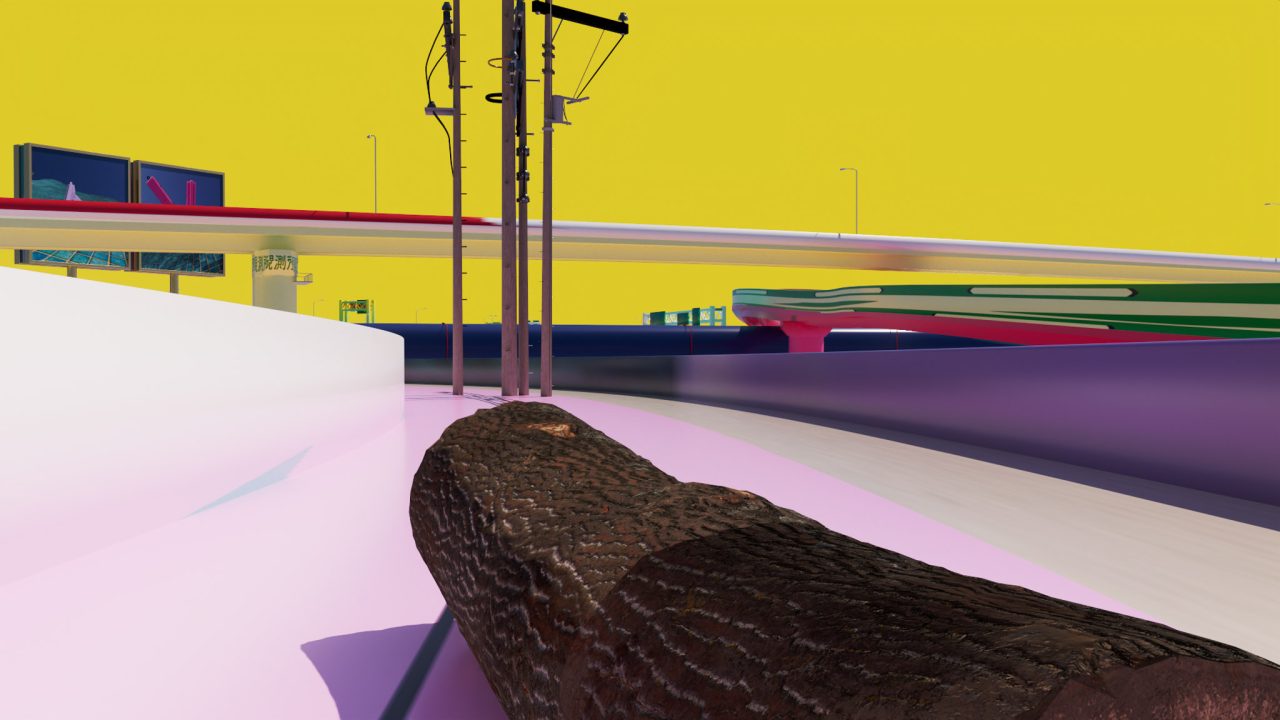

The CV is a piece in which a fictional landscape is constructed by consecutively translating words uttered in the dialogue between objects and humans into videographic elements such as color, composition, form, movement, scale, speed, and depth. Already by describing it in this way, we deviate from the conventional use of the term translation. In this piece, translation is not applied as a direct act of faithfully substituting the meanings of words with corresponding visual imagery, but as a process of generating leaping—and sometimes even contradictory—visual associations that are triggered by words. We have retrospectively identified several tendencies in the types of translation applied within the piece that we were not conscious of during production.

First, there is a tendency for literal translation, whereby metaphors and idiomatic expressions are visualized with startling directness. For instance, when the Brick Terrace utters the words, “Wait, walls, please come back”, a red wall appears on screen, moving toward us at high speed. Or again, when the human says, “In hindsight, there was a turning point”, the camera literally turns around, bringing into view an expressway junction.

Second is the tendency for contradictions and ambiguities to be visualized directly as they are, rather than being denied. Consider the following line, for example: “Thinking is like how, when you walk, with each step forward, you hesitate. In that moment, there is an active agency in the act of stopping. So you must be thinking about where you are headed.” The corresponding visualization is a scene of a fictional expressway. Traveling along it is a cluster of utility poles and a giant log, which abruptly stop and go. The contradictory situation evoked by the dichotomy of proceeding and stopping embedded within the script is allowed to materialize on screen instead of being resolved.

-

"Thinking is like how, when you walk, with each step forward, you hesitate. In that moment, there is an active agency in the act of stopping. So you must be thinking about where you are headed." Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Construction Video, 2025.

©︎ Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura

Third, there is a tendency for abstract concepts to be rendered with almost obsessive concreteness. For instance, the words “something that’s not solid, something more imaginary than real” summon an array of hollow objects, which fall into a vessel in ways that reflect their particular physical properties.11 This triggers a peculiar sequence featuring strange orange-colored objects, possibly artificial, possibly natural, whose strangeness acts directly upon the body of the viewer.

-

The hole is something that’s not solid, something more imaginary than real." Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Construction Video, 2025.

©︎ Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura

Lastly, there is a tendency to manifest not the meanings of words but the sensations they evoke. The Pensilina’s line from earlier provides a clear example: “Could it be… that orange, spiky thing, that awaits with outstretched arms…? That thing, I fear that thing!”12 This triggers a peculiar sequence featuring strange orange-colored objects, possibly artificial, possibly natural, whose strangeness acts directly upon the body of the viewer.

-

"Could it be…into that orange, spiky thing, that awaits with outstretched arms…? That thing, I fear that thing!" Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Construction Video, 2025.

©︎ Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura

The CV offers neither closure nor resolution. The viewer should continually fail in their attempts to bring meaning into focus. Regardless of its incomprehensibility, however, the screen, suffused with rich color and depth, compels one to keep watching. This notion of making the screen visually fulfilling in every scene was something Fujikura and I consciously thought about throughout production.

6

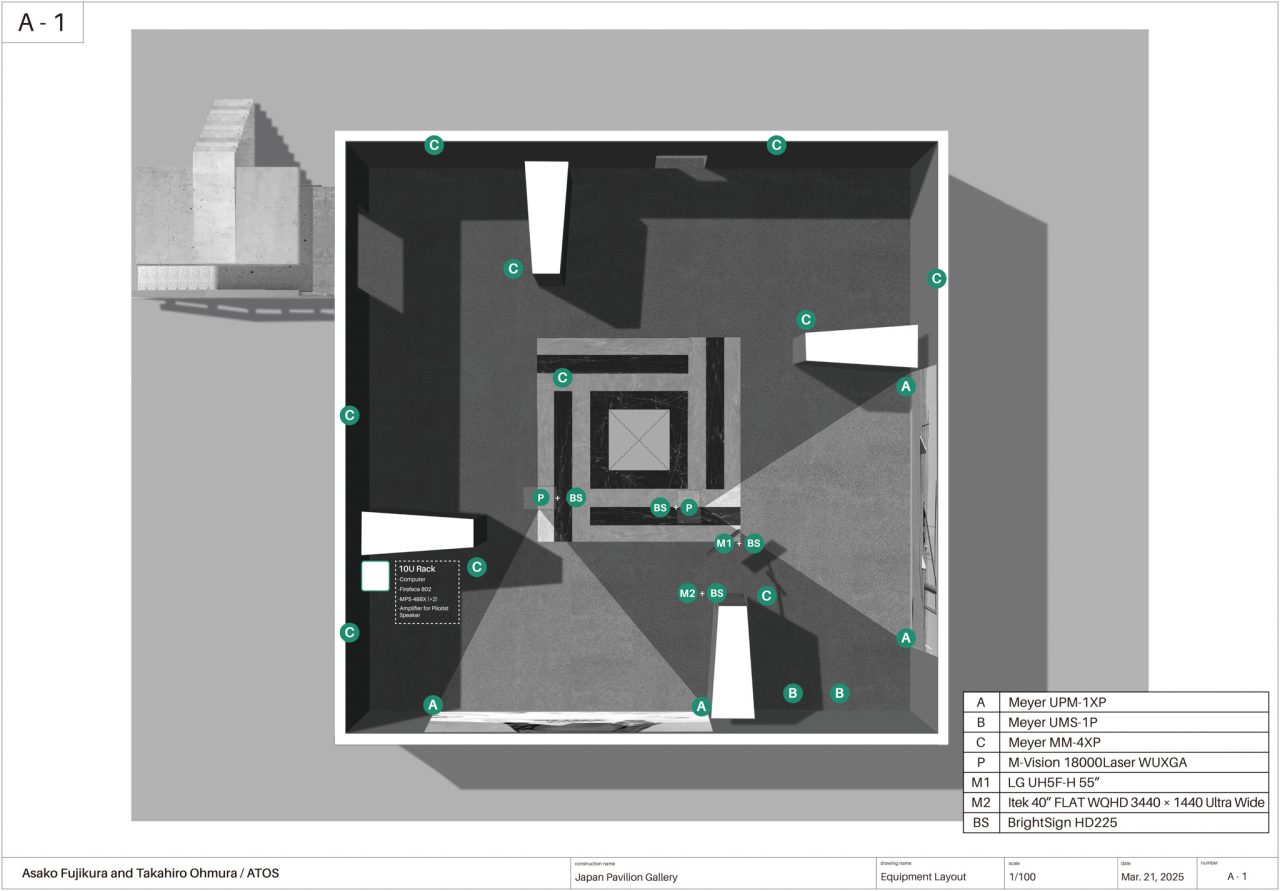

The scenography of the gallery is designed to position the viewer not as a static receiver of the videos (rejecting the passivity implied by the word view) but as a dynamic body existing within the in-between, where various words and sights coincide. As we concurrently developed the video and audio, installation layout, and display equipment, we consciously aimed to build up a structure that would generate reciprocal resonance among these components and elicit active engagement from the viewer.

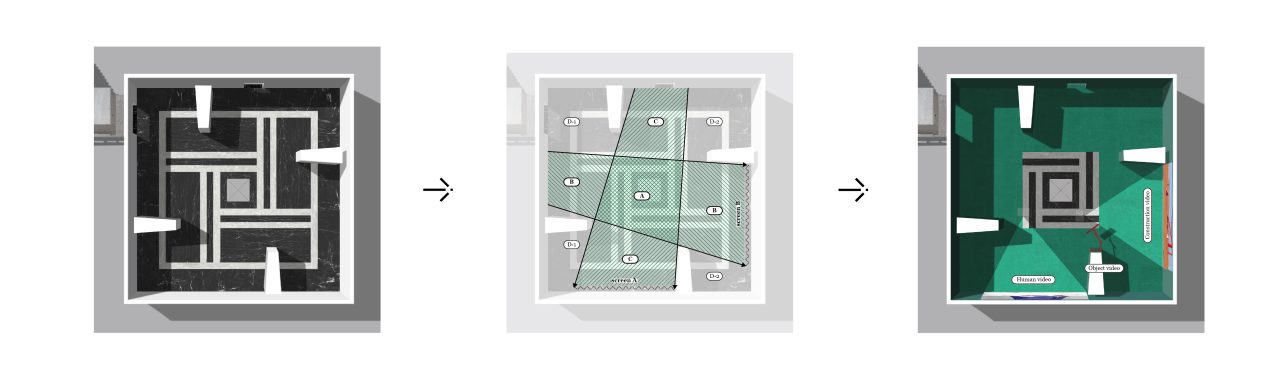

Our first task was to determine how the HV and CV should be arranged. Using regulating lines extended between the wall columns, we identified the largest possible screen sizes that would allow both videos to occupy the viewer’s field of vision simultaneously without being obstructed by the wall columns. This arrangement created distinct zones within the gallery, as shown below.

-

A: Central zone, where both videos simultaneously fill the viewer’s field of vision.

B: CV-focused zones (limited visibility of the HV).

C: HV-focused zones (limited visibility of the CV).

As a result of this zoning, the wall columns do not function as visual hindrances but as devices that facilitate switching between distinct viewing modes. When the viewer focuses on one video, the other video is naturally pushed outside their field of vision. When shifting attention, they then will reposition their body within the gallery while rotating their head (in a way that resonates with the formational principle of the pavilion).

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

Another key design element is the audio layout, which works in tandem with the rotational movement of the viewer’s gaze. Sixteen speakers are distributed throughout the gallery, positioned so that the voices of the actors are heard from the direction in which each actor “exists”. Sounds of humans speaking, chewing, and handling tableware emanate from speakers beside the HV screen, while explosion noises, construction noises, and other fictional sound effects are played from speakers beside the CV screen. Ambient music composed by Ermhoi permeates the entire space.

The Japan Pavilion is a highly reverberant space—it has even been likened to a sentō [bathhouse]. However, sound artist and engineer Makoto Oshiro successfully realized a sonic environment in which each individual sound can be heard with clear separation (with pointillistic clarity, so to speak). The setup enables the viewer to autonomously switch the focus of their attention by reorienting their ears, just as they do with their gaze.

We also designed and fabricated a bespoke stool as a device for physically supporting the viewer within the gallery, whether in motion or at rest, to keep them constantly aware of their own body. The viewers can freely reconfigure the stools, which separate into a Box Unit and Wheel Unit, roll them around, and use them to view the videos from any position they choose. The casters attached to their legs (specialized casters with metal brackets that act like springs) have a cushioning effect, causing the stool to slightly wobble when sat upon. This subtle motion gives the viewer a tangible sense of “I am here”, establishing an intermediate set point for an introspective feedback loop oscillating between fiction (the videos) and the real (the gallery).

-

Photo: Yurika Kono

7

What we sought to explore through this installation was the possibility of distinct beings existing together with their incommensurability left intact. Here, the state of “existing together” is established not by synthesis or separation, but the deliberate choice to connect despite being misaligned.

What the dialogue of this work questions is not merely the conveyance of meaning. When the Pensilina expresses its fear of the “orange, spiky thing”, for example, the audience cannot digest these words directly as presented. Instead, they must try to comprehend them by hearing them as something emanating from a non-human body and reconstructing the object’s perceptual structure in their minds. We set up the CV precisely for this purpose. The act of imagining the speaker’s perception (how their body is composed and how they relate to their environment) establishes, on the listener’s side, a core around which dialogue is able to take shape. This is not limited to situations involving humans and non-humans; the same happens with all dialogues in general.

The in-between is not a site for facilitating understanding or empathy. What it manifests are unstable relationships, fragilely sustained only by the will to maintain engagement despite the unresolvable misdeliveries, frictions, and loneliness each must bear. We wanted to try putting forth the idea of “just keeping the dialogue going”—as a framework for intelligence and creativity, or for living and generating—within this world where everything is determined by plausibility.

Think of how, in architecture, the term fit can refer to a state of connection that allows for movement between clearly distinct objects. It is a dynamic mode of connection that deliberately permits wiggle room and gaps between components—or, in other words, one that accepts the unresolvable rifts between disparate entities. As such, creaking and warping can inevitably occur. The in-between is not like a tightly sealed fixed window, but more like a poorly fitted door and frame. We have the option to deliberately inhabit the gaps between incommensurable voices.

Notes

1: Script translated by Sky Araki. Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Construction Video, 2025.

2: Ibid.

3: Ibid.

4: Ibid.

5: Ibid.

6: Ibid.

7: Taichi Sunayama, “Mada tatteinai: Tokushū: Kenchiku no imēji/kotoba ni yosete” [Not yet built: Introduction to the special issue ʻImages/Words of Architecture’], Kenchiku Tōron, May 31, 2024, https://medium.com/kenchikutouron/まだ建っていない-建築のイメージ-言葉-19723a481456.

8: In October 2024, the first draft of the script was still at a stage where “all the lines sound like Ohmura” (feedback courtesy of Kiuchi). Hoping to remedy this, I passed the script on to Fujikura. She completed the second draft, which was much richer (especially the lines of the objects) thanks to her unique linguistic sensibility. A third draft followed, incorporating feedback from the team. I then trimmed the script down to meet our target runtime of approximately fifteen minutes. By the time I finished this fourth draft, which became more or less the final version, the calendar had turned to January 2025.

9: The meal was prepared by the food designer Kaoru. The dishes, which feel distinctly Japanese yet seem to belong neither to the present nor the past, evoke a peculiar texture that seamlessly blends the familiar and the unfamiliar. The costumes, which are individually striking but achieve a mysterious sense of cohesion together, were realized in collaboration with the fashion brand Kolor (designer: Junichi Abe), known for its creative material juxtapositions and compositional style.

10: The lines were adjusted for each performer so as not to clash with their accustomed diction and delivery style. For some of the longer sequences, we recorded the performers as they shadowed staff members reading the lines aloud, and their voices were dubbed in post-production.

11: Specifically, a steel tube, hose, air duct, transparent plastic tube, plumbing pipe, balcony railing, window frame, chair back, fence post, car wheel, vacuum cleaner hose, goal frame, tailpipe, frying pan handle, bicycle frame, surfboard fin, power line, antenna, ladder, bucket, cooking pot, umbrella frame, rain gutter, film canister, handcart handle, birdcage, sign holder, power cable, crayon case, tent pole, picnic table legs, and rope.

12: Here, the Pensilina is likely channeling the feelings of the birds that often perch upon it. From the perspective of a bird, the color orange is highly likely to signify food, such as fruit. However, orange is also commonly used on artificial objects, such as construction workwear. Perhaps the birds were frightened after mistaking workwear draped on the Pensilina for fruit.

Takahiro Ohmura

Architect. Born 1991 in Toyama, Japan. Ph.D. (Engineering). Assistant Professor at the College of Engineering at Ibaraki University since 2023. Through engaging in architectural design, research, critique, and writing, he has been exploring the possibilities of communality for supporting and encouraging the sustenance of life in post-urban conditions—namely, the suburbs and hinterlands—and locating emerging necessities for architecture therein. Notable works include In-Between (Japan Pavilion exhibition for the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2025); The Garden Beside Whitehouse (as a member of the architectural collective GROUP, 2021); and Fixing Garden (with Asako Fujikura, 2022–). Awards include the 2019 SD Review Merit Award for the Detached Building at Kuragano Station (with Naoki Saito).