Series Windows in Chinese Architecture

Part 5: To China International Window City!

22 Aug 2018

The aperture in Japanese architecture is the “ma,” or “space between objects.” The aperture in western architecture is the “hole.” What is it in Chinese architecture, then? This is a study on the as of yet unknown culture of windows in Chinese architecture from classical times to the present day.

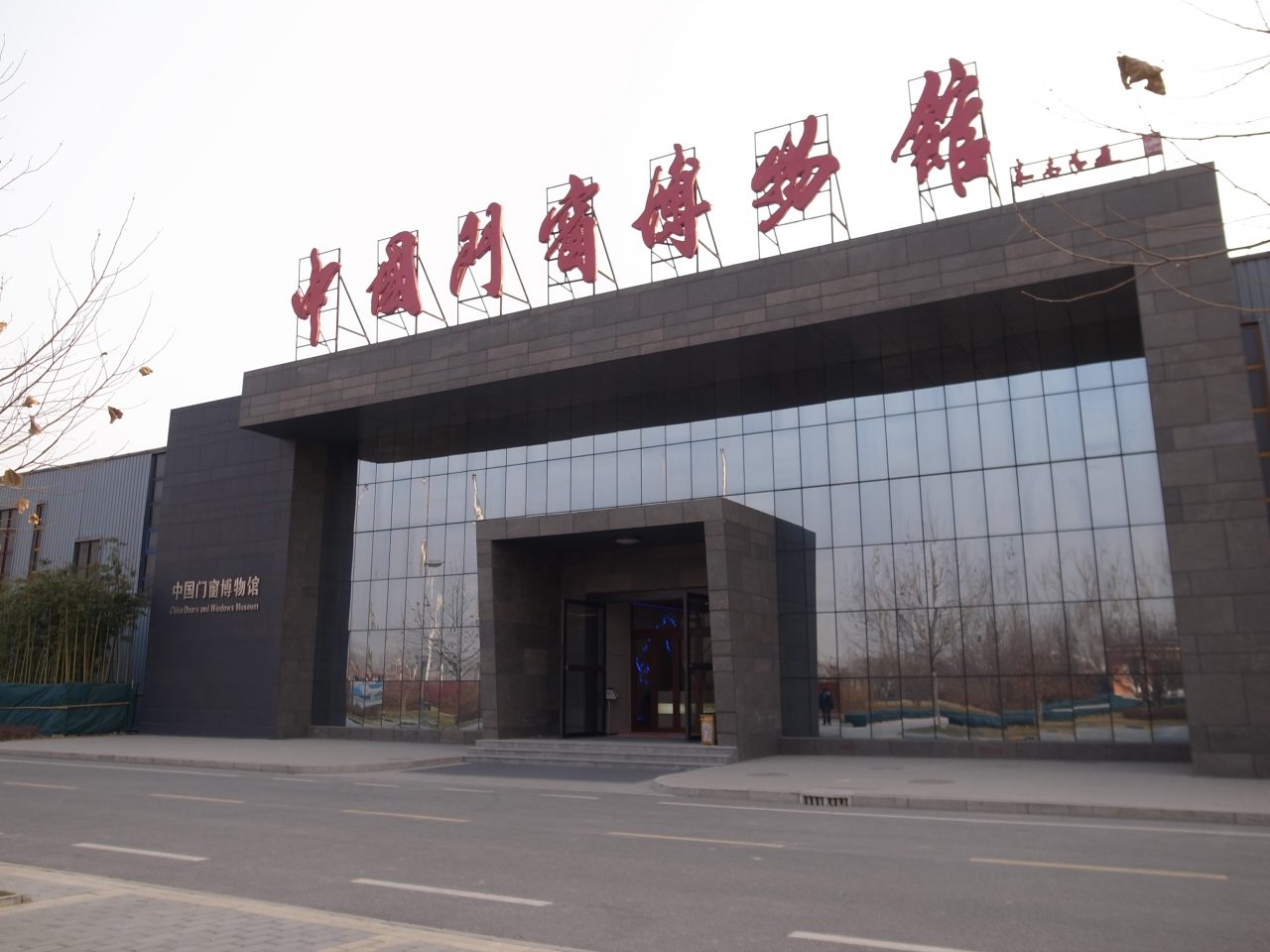

South of Beijing, in Hebei province’s Gaobeidian city, is an institution called China International Window City. According to its homepage, it is Asia’s largest door, window, and curtain wall industry exhibition and trade center. It is a massive institution with a general use space in which companies from all over the world set up booths during the annual China Gaobeidian International Door & Window Festival, along with model rooms equipped with real products and a college that teaches about doors and windows on a specialist level. It has been on my mind since I started writing this column, but since it is difficult to get there without a personal car from Beijing, I have not had an opportunity to visit it. However, just last weekend one of my co-workers happened to be free to take me there, so I was finally able to check it out.

Seeing it in person, I found that it was made up of 6 massive warehouse-like buildings, inside of which were several displays that were left there after the year’s International Door & Window Festival, which was held in September. It was separated into a space for window and door products, and a space for materials used in the production of windows and doors, and I suspect that the most high-tech products in the world were on display. I would love to visit during the festival next year so I can talk to each of the companies about what kind of windows are doing well in China currently.

-

China International Window City

-

China International Window City

One thing I found interesting was the fact that optical illusion paintings were scattered about the premises. The plan is for the space to occupy 1650 mu (a mu is a Chinese area measurement. 1 mu is 1/15 of a hectare, so 1650 mu are approximately 25 square kilometers), but it is still in the process of development. They are trying really hard to make the space appear as large as possible, so perspective paintings that make it seem as though the space continues on are put in place at dead ends inside and outside the warehouses.

-

China International Window City

-

China International Window City

Optical illusions were often used in paintings in the Netherlands in the 17th century, but in this case, in order to confound the onlooker, the edges of the paintings are made to appear as though they were the edges of windows. These optical illusion paintings make clear the similarities between the act of appreciating the space within a piece of painted art and the act of gazing outside through a window. Perhaps I’m reading too far into it, but I imagine that they were aware of these similarities when they decided to install these optical illusions about the establishment.

Next to China International Window City is the establishment that worked on building it, Gaobeidian Shunda Moser Window & Door Co., Ltd. I asked around a bit and got a basic understanding of the background of China International Window City’s construction. Shunda only had 8 employees in the beginning of the ʻ90s, but now has massive joint stock with a German company, and a portion of its stocks are owned by Gaobeidian city as well. The city has plans to support the development of door and window production as its banner industry, so it built the massive institution that is China International Window City in order to support the industry while also promoting it on a social level. Shunda’s office building is a symmetrical behemoth, and its intimidating presence is typical of government buildings in China. One can understand why it is designed in such a way if the city government is backing up the company.

-

Gaobeidian Shunda Moser Window & Door Co., Ltd.’s office building

The only thing at China International Window City that was running year round was the “International Door and Window Museum,” which was located in the corner of the premises. The museum had everything from ancient wood, stone, and lapis lazuli doors and windows, to glass windows from the early-modern and modern periods on display. I introduced stone windows and wooden windows and gates from Ming and Qing dynasty gardens in my first post, “The Window in Classical Architecture” and my second post, “The Gathered Gates and Windows,” but I did not discuss the changes gates and windows went through before that period, so I would like to survey that historical background here.

-

China International Window City

-

China International Window City

One can summarize the history of the development of windows and gates in Chinese architecture by saying that they became increasingly richly decorated, gaudy, and in some cases the surfaces more curved in time. Decorations were applied to doorways and gates of residences since the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE), but those decorations were no more than simple geometric shapes and simplistic renderings of animals. Window lattices were simple vertical bars. This characteristic simplicity did not change with the Tang dynasty (7th century to 10th century CE), and the design of apertures we see in places like the Great East Hall of Foguang Temple (built in 857) consist of vertical latticed windows and planked gates. After that, decorations became richer with the passage of time. In the bureaucratic architectural rulebook “Yingzao Fashi,” of the Song dynasty (10th century to 13th century CE) the designs and methods by which gates and windows were to be made are set in great detail, and with the advancement of craftsmen’s techniques, a new peak in gates and windows that were both practical and highly decorative was achieved in China. However, with the passage of yet more time, contrary to what one might expect, decorations became looked upon with more importance than practicality. As I wrote in a previous post, in the Ming and Qing dynasties (14th century to 20th century) many windows and gates were decorated with elegantly curved lattices and carvings that speak of their history. The design of decorations for gates and windows took on a particularly important role in the overall configuration of buildings.

The patron of Chinese architectural history, Liang Sicheng (1901-1972)’s opinions are very interesting when considering the above change in the design of windows and gates. Liang Sicheng, who studied architecture in the United States, said that from the perspective of modernist rationalism, one can think highly of Song dynasty buildings, the structure of which embodies the beauty of architecture, while saying that there is an overabundance of irrational decorations present in Ming and Qing dynasty buildings, making them undesirable. When he made this judgment, he was focusing particularly on the design of pillar and beam meeting points, called dougongs, but when looking at gates and windows, the differences between buildings of these periods are utterly obvious. Because the process of creation had reached a certain level of completion by the Song dynasty, and the materials being used became lighter, craftsmen developed further the minute details of window and gate carvings and lattices. The delicateness of some is such that one must have hesitated to touch them in their day to day life. According to the introduction of the museum, throughout the evolution of Chinese architecture, the pieces which changed the most are windows and gates, and by turning this on its head, one can get an overall sense of the history of Chinese architecture, which is vast, by focusing in on them.

Kouji Ichikawa

Born in Tokyo in 1985. Currently he’s in a doctorate program in Tohoku University’s Engineering Research Department. His research topic is the theory and history of pre-modern and modern Chinese architecture. He is the editor in chief of the amateur architecture magazine “Nemoha.”