Series Traveling Asia through a Window

A Desert Below Sea Level—Turpan, Part 2

22 Mar 2017

I came across a group of grape-drying huts on a hill just off the settlement. These huts I had seen the day I arrived in Turpan while taking a bus to my nearby accommodations some 10 hours after an exhausting train ride. On a hill under a harsh morning sun, those perforated buildings all faced in the same direction, attracting my sleepy eyes.

Cutting through the Uyghur settlements I’m heading to that bald hill lined with huts. Most of those huts, lined neatly on an incline, are made of sun-dried bricks. The huts have the same color as the hill they are standing on. A hill transformed into huts through water and sun. Some huts used burned bricks while some were empty lots whose foundation is all that remains.

-

Grape-drying huts. The transformation of a hill through water and sun

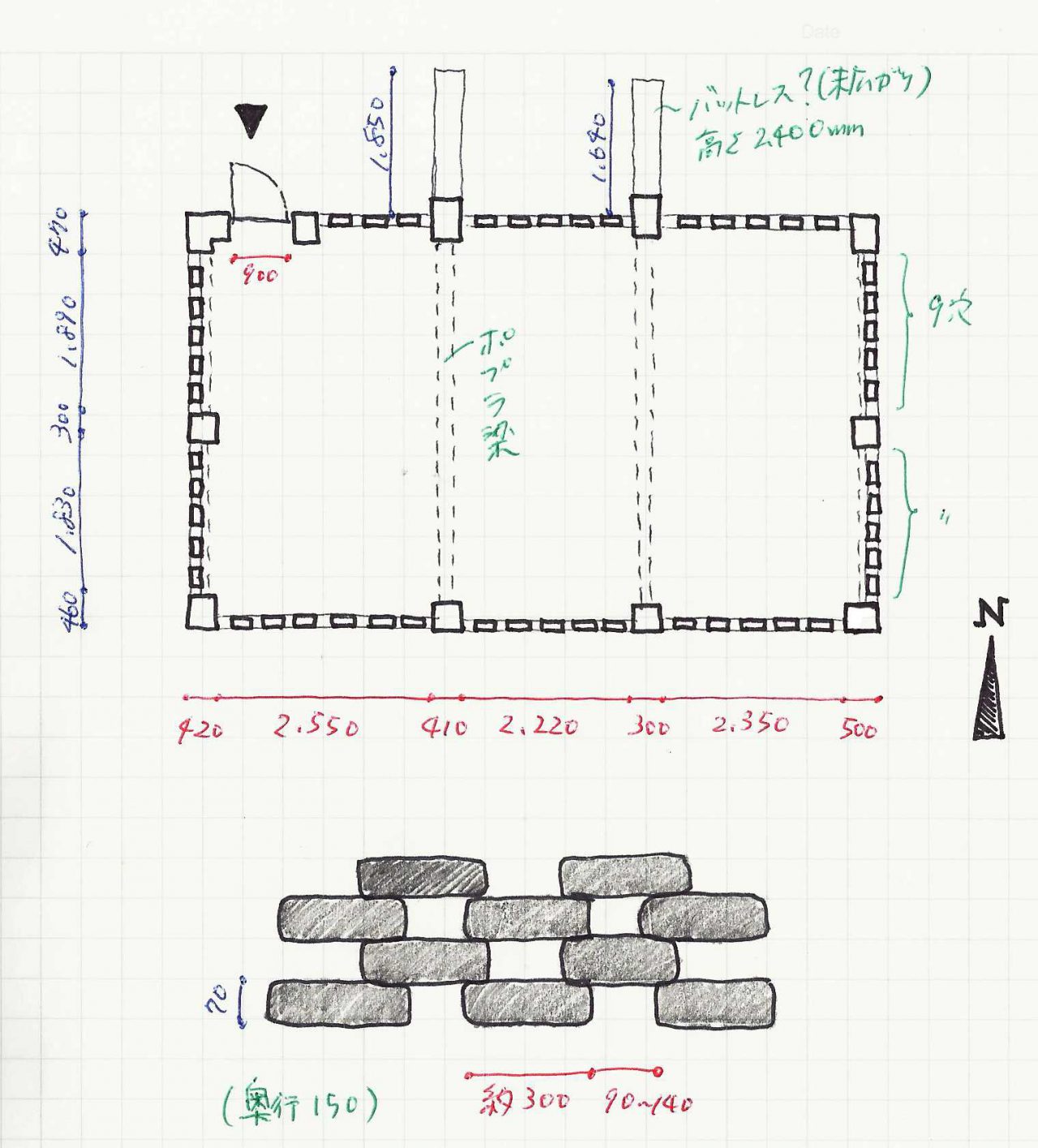

As it seems no one is home, I decide to begin measuring, under the scorching sun, one of those unlocked and old-looking sun dried brick huts. The opening is also made of sun-dried bricks stacked in a staggering their position. The walls are perforated all over.

-

A grape-drying hut with perforated walls

Two poles of dried bricks were attached to the front wall. I imagine they served as a buttress which was often employed in European churches in the ancient and medieval eras (A buttress is a supporting structure that sticks out from a main wall and can be attached at a right angle to strengthen it ).

Something resembling branches and leaves cover a thin poplar pole that serves as the hut’s roof. As it hardly ever rains this is more than enough.

I enter the hut.

-

Inside of the hut. A strong contrast between light and shadow

The shadings were beautiful. The contrast between light and shadow represents the intensity of sunlight.

No other walls and roofs like this can be loyal to the climate of Turpan. Picking up the material available to them, builders used a roof to make a pitch-dark shadow in response to its scorching sun while the walls supporting the roof are perforated so that a breeze can enter. While all of the huts are for grapes, it is certainly a comfortable space. The long side of the hut faces north and south because it is better for drying since the wind blows through them.

It seemed to be just before harvest time. Because there was nothing inside I could clearly discern the structure of the hut. The perforated walls may have been utilized for grape drying.

-

A floor plan of the grape-drying hut (above), Stacking pattern of sun-dried bricks (below)

Beams of poplar dart out of the wall. Only the sections falling under these are not perforated, causing them to look like a series of patterns.

-

Joists of poplar are dart out of a wall

Interestingly, some Uyghur settlements have their grape-drying hut on the second floor of their home. If there are no hills such as this one nearby, they combine the hut with their home, using a well-ventilated second floor for drying.

-

The city center of Turpan with a grape-drying hut above a restaurant

There is a reason why I am so interested in these huts. The fact is these grape-drying huts represent the basic structure of the Uyghur settlements I will discuss later. In short, most of the dwellings are made by bricks (sun-dried or burned), poplar, and a few branches and leaves that create shadows and an airy room. That is the essence of a dwelling in a desert below sea level.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.