Series Traveling Asia through a Window

A Desert Below Sea Level — Turpan, Part 1

08 Mar 2017

What kind of place is a desert below sea level?

-

A view of Turpan from a hill lined with huts drying grapes. Despite the desert climate the green is lush.

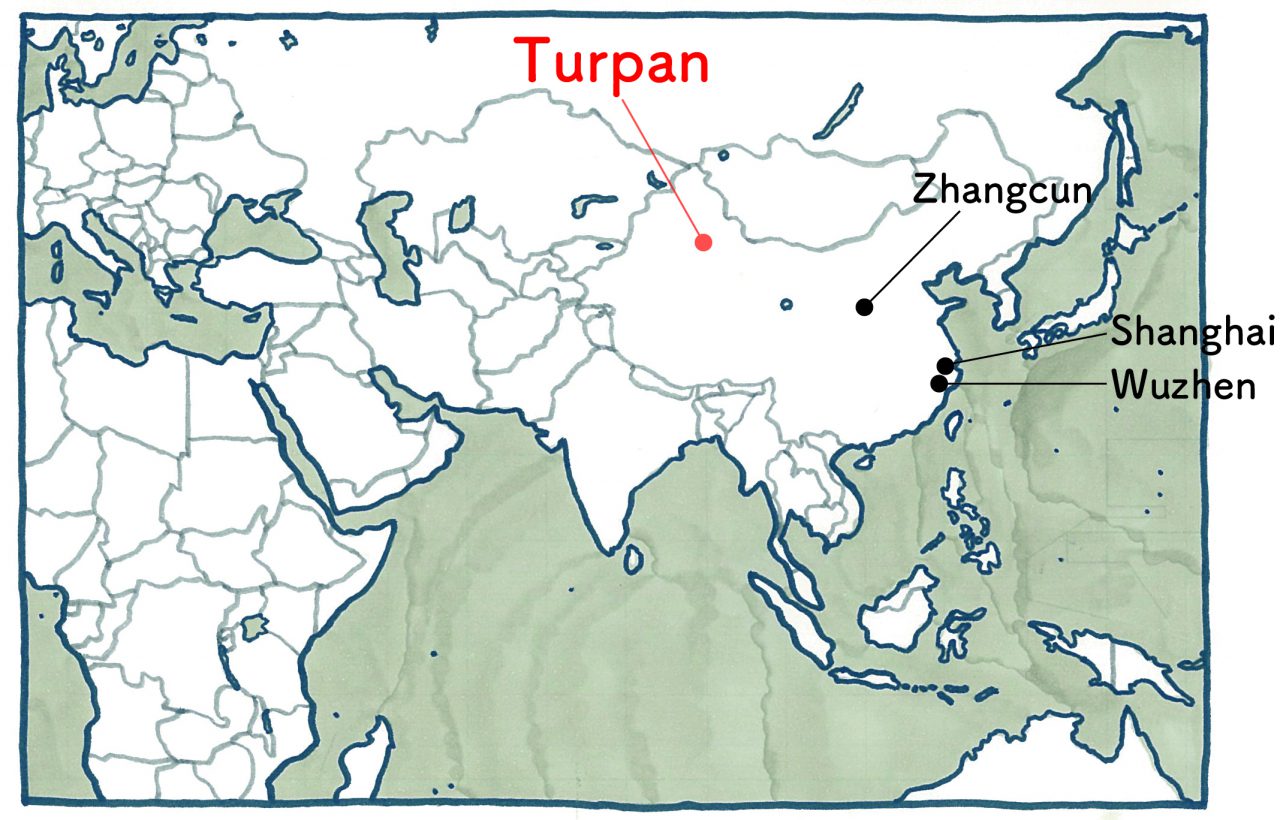

Turpan is located in the west of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, an autonomous region of China. The city has long served people as an oasis of the Silk Road. Located in the Turpan Basin near the Taklamakan Desert, the majority of residents are Uighur. Most of the land is below sea level, and its people has survived by drawing melted snow from an original water system, a karez, from Tian Shan in the north.

Despite annual precipitation of less than 20mm, foliage grows thickly in this area. It is one-hundredth the width of Tokyo. Because of its desert climate it is a rough place to make as one’s home: the temperature surpasses 40℃ in summer but falls below 0℃ in the winter. Here the loesses of Yaodong that have been carried around by the wind accumulate here.

I visited Turpan during the heat of midsummer. Walking under the scorching sun, I cooled myself within deep shadows whenever I came upon them. Shadows are cool and comfortable in this dry land.

The settlements of the Uighur are built along the karez. Within the settlement, the karez runs along both sides of the street, casting shadows among the poplar trees lining the street. I imagine the poplar trees also function as a shield from the strong wind and accompanying sand.

-

On the main road of the settlement. A Uighur woman walks on the street holding her child’s hand.

There used to 1784 karez all over Xinjiang but most have been replaced by waterworks. In Turpan there are 404 remaining, though they are being abandoned one by one. With the good accompanying the bad, modern technology changes the landscape of the settlements from all directions. By looking at these remaining karez, perhaps we can glimpse a scene unchanged for ages, for example that of a mother bathing for her child.

-

An Uighur mother give bathing for her child in Karaz.

The karez water system is made by wells dug at regular intervals from the base of a mountain that is connected below ground. Seen from above, the wells look like holes dug up by moles. The waterways run underground so as to avoid evaporation. They appear above ground just before the settlements, running from there through the dwellings and fields.

It is a harsh environment, but the inhabitants take advantage of the land, even cultivating fruits. Long hours of sunlight and low rainfall, or the temperature gap between day and night, makes the desert climate hard for people to live in but it also sweetens fruit. Fruits line the streets, and Uighur mothers buy an incredible amount. A long and thin melon, called the Hami Melon, sells for about 60 yen. Eating them every day, I thought of merchants from two thousands years ago.

-

A man selling Hami Melons on a street. It is a sweet melon with a crisp texture.

Creating a shadow is the first thing to do here if you want to survive the summer. At the same time, air must pass through it otherwise it will be too hot.

To see the dwellings in Uighur I ride a bicycle while putting a wet towel on my head. I came across curious huts. These huts were drying raisins, their local specialty. They stand on a barren hill above the settlement, looking like modern buildings when seen from a distance.

First, I decided to climb on the hill by myself and observe these peculiar huts.

-

Huts drying grapes seem from a vineyard.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.