Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Zhangcun: The Needs of the Underground Part 3

26 Jan 2017

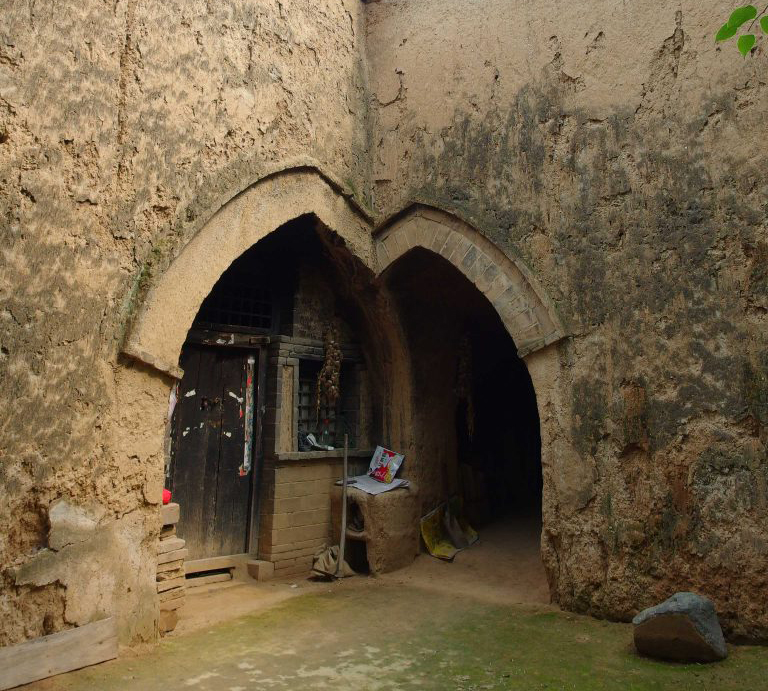

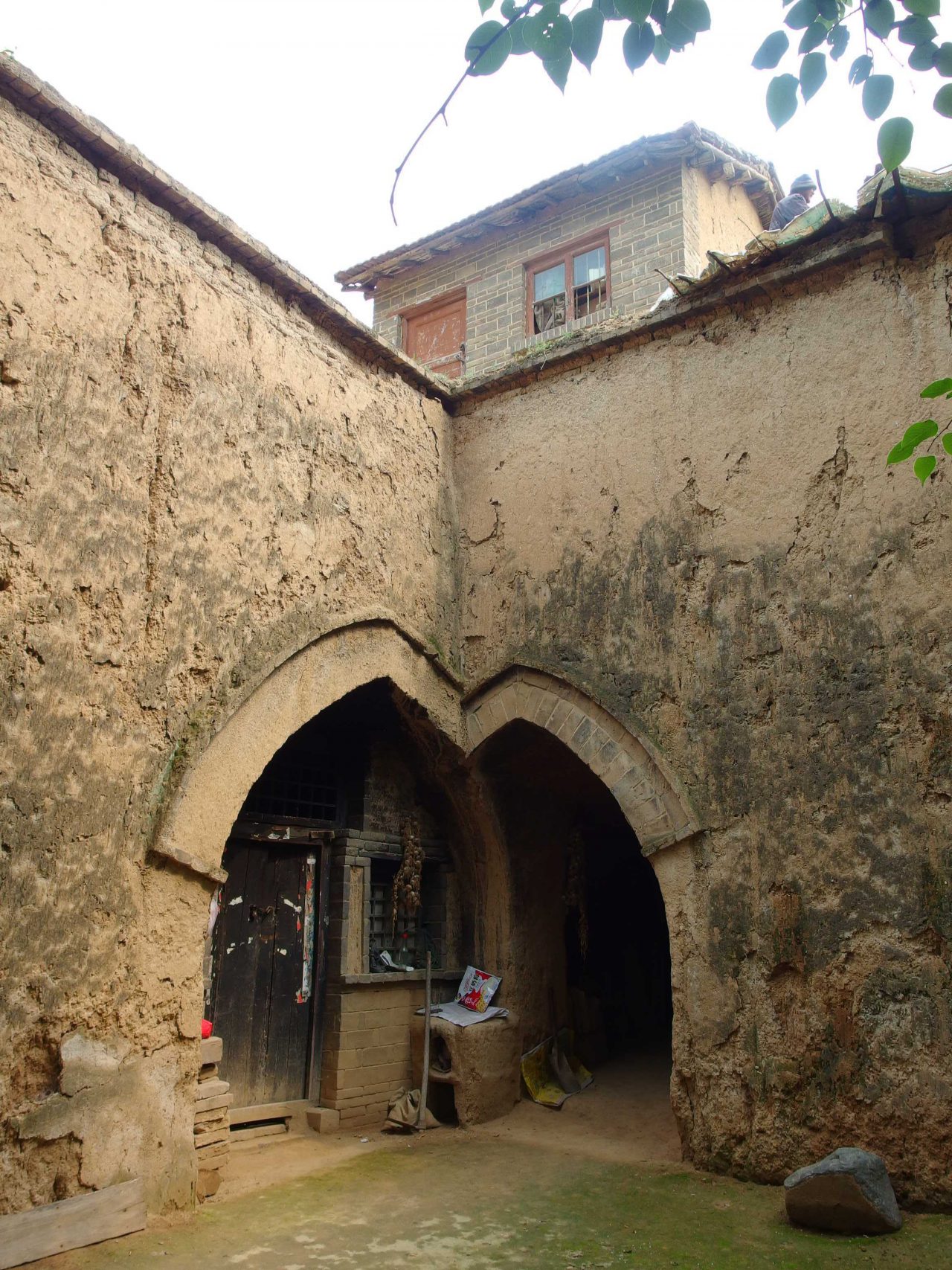

I realized something was strange here in the centenarian’s Yaodong. The entrances to Yaodongs are generally shaped into a pointed arc, but upon closer inspection, I noticed that the corner arches were only half-finished.

-

The centenarian’s Yaodong. A corner arch is left half-buried.

Come to think of it, there was a similar arch in the old woman’s Yaodong, too. Looking through the photos I took, every Yaodong I stayed at – including my current lodgings – had a similar construction. I had only assumed there to be a series of complete arches in a Yaodong, but this was not the case. How were they created?

-

Conjoined Arches

Later I looked into the way these arches were constructed.

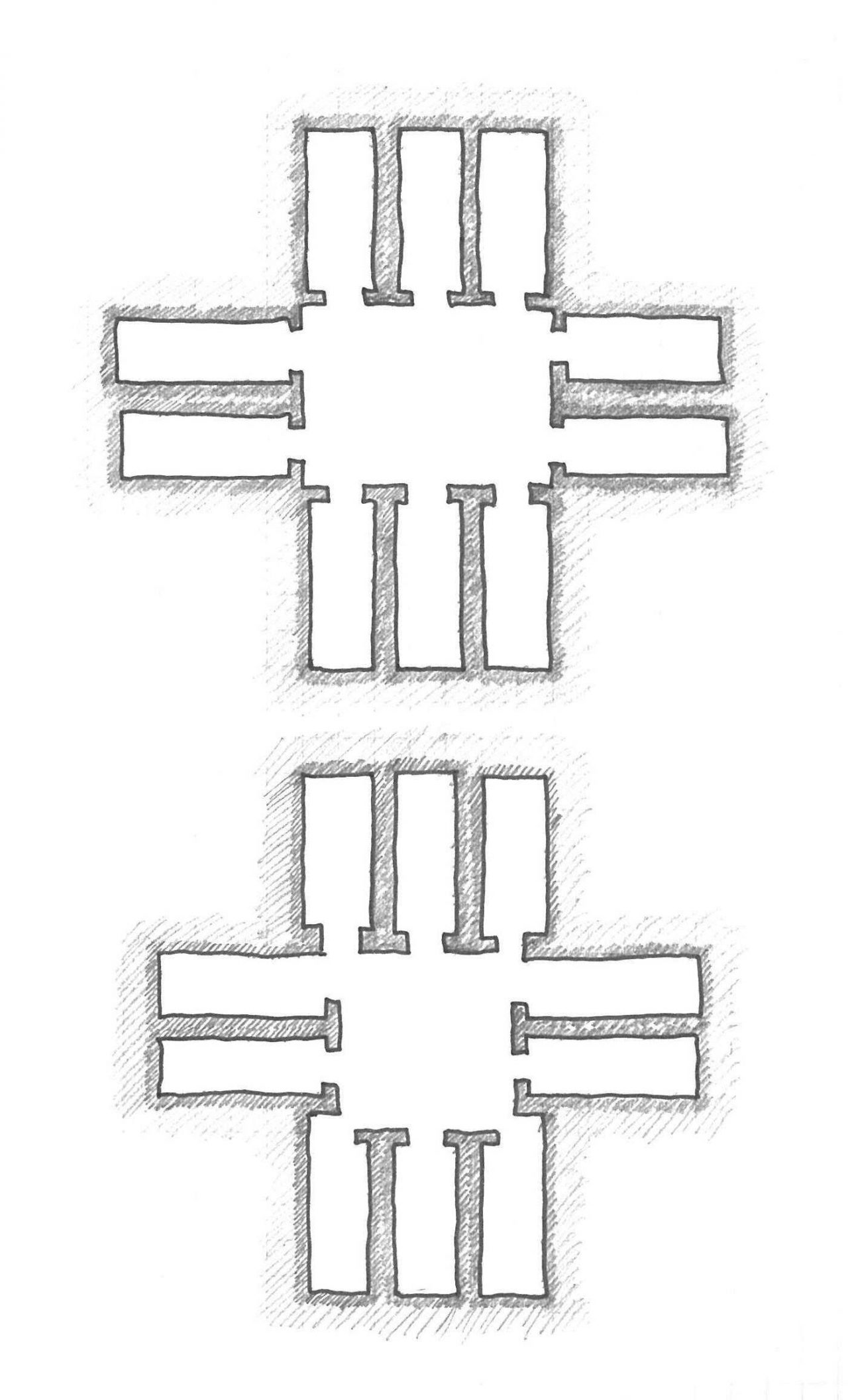

Consider the following schematic outline below: in order to dig three rooms above and below and two rooms to the left and to the right in order to create a square hole in a courtyard, one would imagine that these rooms are arranged at equal intervals, like the first drawing below. But in reality, Yaodong’s were created following the second drawing.

-

A schematic outline of the Yaodong. Soil quantity of excavation is smaller in the plan view below. The size of rooms are same.

Both Yaodong are similar in terms of the number and size of rooms. In terms of the actual construction of a Yaodong, however, because corner room are arranged as closely as possible to each other, and sometimes because they even share an entrance, the area of the courtyard may be reduced by up to two-thirds.

This is due to the difficulty associated with excavating soil, a simply rational reason. The fact that this attempt at reducing labor results in the construction of very variations in openings is both wonderful and charming.

-

Joint of an arch and a square opening

In the picture above, an arch and square opening join at the corner. This is a half-outside space furnished with a furnace. It becomes a slightly ambiguous place not unlike the spaces under eaves or the earthen floors often encountered in Japanese architecture.

It is hard to imagine that such a design was planned from the outset. One might say that it is a unique opening resulting from this culture’s hundreds and thousands of years of excavation in the loesses.

In other words, in this opening at the corner, we can see an original design created by “the needs of the underground.”

“The needs of the underground,” which are the norm for the people living in the loesses, seems pretty original for the “people above ground.” Even in this village, too, residents are moving above ground, and the Yaodong are starting to be abandoned. But even if those caves are buried again, it’s said that new houses won’t be built above them. The loss of “the needs of the underground” will remain for hundreds of years to come.

-

A house above ground. Even though they got brightness and wind, the custom of putting news papers on the wall is remaining.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.