Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Swiss Window Journeys: A Conversation between Andrea Deplazes, Laurent Stalder, and Momoyo Kaijima

17 Dec 2024

On 12 April 2024, to celebrate the publication of Swiss Window Journeys: Architectural Field Notes, the Chair of Architectural Behaviorology organized a walking tour of notable windows across the city of Zurich. The tour ended at the Never Stop Reading bookshop in Niederdorf, the old district of Zurich, where Momoyo Kaijima, Andrea Deplazes, and Laurent Stalder engaged in a conversation around the role and meaning of the window in Swiss architecture and beyond.

Momoyo Kaijima (MK): The book brings together a number of interviews in which we talk to Swiss architects about their approach to window design. I was keen to have one last interview with you, Andrea, not only because the book includes the New Monte Rosa Hut, an educational research project you carried out with ETH, but also because I’m a big fan of your work. So, my first question tonight refers to one of your early projects, the Tower House in Sevgein, which has very interesting windows. In the living room, there’s a very large window that extends the glass surface across the entire width of the space, and then you have other smaller windows that seem to be almost punched out of the wall. What was the idea behind those windows?

-

Tower House in Sevgein, Switzerland (1998) by Bearth & Deplazes © Ralph Feiner

Andrea Deplazes (AD): This house was for a family who wanted to live in a very nice place with views over the Rhine Valley. Our initial proposal was to minimize the presence of the building—to integrate the house as a one-storey structure in the section of the slope. But the family wanted to have something more compact, distributed over several storeys. So we pushed everything together and the footprint of the house became smaller but taller. In the living room there’s what I would almost call a missing wall, replaced by fixed glazing, allowing spectacular views over the valley of the Rhine. The other rooms are organized vertically in a split-level distribution with an open staircase. For the room at the top, in the roof space, we used a Velux window, which we liked because it integrates everything from the shading to the connection to the construction so that it can be installed like a DIY solution. Windows which tilt open like that—half inside and half outside—are usually very expensive, so we thought: Why not use them as a readymade on the façade as well? The manufacturer objected that their windows were designed for the roof. And we told them: Yes, but the windows don’t know that we’re putting them on the wall rather than the roof because the details are the same. Velux wouldn’t guarantee the windows because they were not being used in their prescribed manner, but we went ahead anyway and handled them like roof windows, installing them from the outside—and by the way we later profited from this experience with the Monte Rosa project. We wanted to have one window in every room that you could open and have natural ventilation and integrated sun shading, without them having to be big windows. In a lot of buildings today the windows have become very big, which can also be a problem. But maybe we can talk about this later. My more immediate question would be: Do houses need windows?

-

Tower House in Sevgein, Switzerland (1998) by Bearth & Deplazes © Ralph Feiner

-

Tower House in Sevgein, Switzerland (1998) by Bearth & Deplazes © Ralph Feiner

-

Tower House in Sevgein, Switzerland (1998) by Bearth & Deplazes © Ralph Feiner -

Tower House in Sevgein, Switzerland (1998) by Bearth & Deplazes © Ralph Feiner

Laurent Stalder (LS): Perhaps I can reframe that, and say: Do houses need openings? It’s probably possible to do a house without windows, but there needs to be at least one opening—for people to enter, or for heat and smoke to escape, if you have a fire—otherwise the structure cannot be used, you cannot access or leave it. It’s a dungeon. Interestingly, Alberti, doesn’t speak about windows as a category, but about openings.

Andrea, you’ve spoken about the composition and construction, but I think the merit of Momoyo bringing in the dimension of Behaviorology is that it focuses on the question of how a window is used. What characterizes the window is the way it expresses the different relations that we construct between the inside and the outside—whether this is purely visual, as a domination of the landscape, or having a window that deals with wind or sun, etc. And all these dimensions—I wouldn’t call them functions—can potentially be articulated by the architect, giving the window a particular quality. So yes, it’s probably possible to have a house without windows and to resolve issues such as bringing in air or light using technology instead. But what the window brings is a spatial dimension.

MK: You said a structure without windows would be like a dungeon, but it feels more like a tomb to me, a place not for the living but for the dead. Life on Earth was sparked by the encounter with the Sun. Air and light are among the basic requirements for life—that’s why we need windows to connect with the outside.

It could be argued that the window is the most developed element in the history of modern architecture. What do you think, Laurent?

LS: It’s a highly developed element because, again, it’s where the boundary condition between inside and outside—between man and the environment, between the individual and society—has to be articulated. And I guess in the last fifty or sixty years a lot of attention has been given to the question of how we can construct this articulation and meet all the new demands, in terms of sound, energy, light, and so on. So probably it is among the most articulated elements. Whether it is the most articulated one, is probably not important to answer.

AD: The façade construction, no matter how it is done, is always the most expensive part of the building because you have this inside–outside relation. If I asked my students “What is a window good for?” they would give me all the right answers. But, going back to my previous question, if I were to ask “Does a house need windows?” it’s not so straightforward.

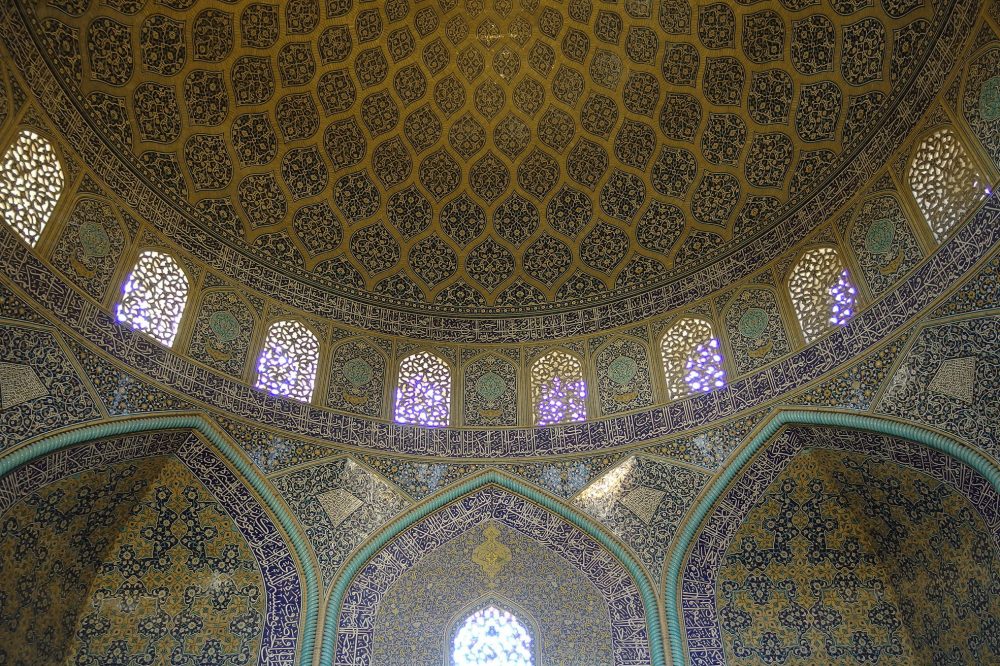

When I was travelling around Iran, I went to wonderful places like Isfahan and Shiraz where the typology is the courtyard house, so you have no windows onto the street. It was so interesting to see parts of the city that had such an elemental character—one that was not overloaded with elements. (On the other hand, you couldn’t imagine the part of the city we’re in now, the Niederdorf, without windows—it would be a real culture shock.)

I think the window becomes something key the moment you realize it’s first and foremost about light. Physicists say that millions of years from now, at the end of the universe, there will be no light, only darkness. When I think of darkness I don’t think of a tomb or a dungeon: I think of an absence of light. Our lives depend on having the light from the sun. As an architect, you have to do things to guarantee this life-sustaining light inside the building. And there are different approaches to doing this. For example, the Pius Church in Meggen by Franz Füeg has no windows, only a thin shell of marble, so thin that light can shine through. There’s no direct daylight, but the whole building glows like a lantern. And this is one approach that gives the light more of a presence—a metaphysical aspect that goes beyond simple metrics like U-values.

LS: Picking up on these aspects of the window that go beyond simple metrics, I have a question for Momoyo. Why has Switzerland—a place where nobody ever speaks about the “behaviour” of windows—proved particularly fertile ground for you to study windows?

MK: When I first came to Switzerland as a student in the 1990s, I felt that architects were deeply engaged with the idea of giving meaning and beauty to each architectural element in their projects. And I wondered why that was. Gradually I began to understand that this was a debate—a culture—that had a much longer history that went back to Semper or even earlier. In Switzerland, the traditional importance of agriculture, combined with the severe climate, has meant that people have had to work hard and to develop their technical, problem-solving skills. This culture is somehow expressed in the element of the window as well. There’s this very old kind of window that we look at in the book, for instance, the “soul window”, a simple slit sawn into a timber beam that could be opened when a person died to release their soul back to the Alps or the sky, and then closed with a piece of wood or a sliding shutter. It’s very lightweight, but at the same time very minimal and very beautiful.

-

View of the "soul window" (Seelenfenster) in a farmhouse in Obermutten, Switzerland © Chair of Architectural Behaviorology

AD: Do you see some kind of connection between Japanese and Swiss culture here?

MK: In Switzerland a window is the result of the process of carving out or punching an opening in a wall, whereas in Japan the climate is milder, so houses are built in a different way. There, the window is about closing the space between two columns supporting the roof, which is usually done with a system of sliding elements. Despite these structural differences, in both places there is perhaps a similar interest in the issue of how to open or close the space and a commitment to solving it technically while taking into consideration the richness of everyday life. That’s why Switzerland has been a very interesting counterpoint for me to describe the behaviour around windows.

LS: Switzerland is also an amalgam of different climates, materials, and construction systems. In very simple terms we could talk about a timber tradition in the German-speaking part and a stone tradition in the south, in Ticino for instance. For a long time, there was a need to respond very closely to the climate of the region and the local availability of materials. But this changed with modernity. Andrea, your description of how you can use a product like Velux not just for the roof but also for a wall is almost a metaphor for a general consensus that you can use any window anywhere in any country, independent of the climate. So, what would you say are the challenges now?

AD: That’s a really good question, because windows have become absolutely independent from where they are used. In Switzerland, windows have become really thick in order to meet stringent energy requirements; they’re now heavy technical interchangeable products that have lost their local specificity. For me one of the most interesting things to discuss is whether the window could have multiple uses (I don’t like the word “function” because it makes it sound like a very mathematical approach). For example, the right kind of window, in the right position, could be used to heat a house—because the light that comes in through the window also consists of warm rays—but you have to think about how big the opening is, so as not to overheat. If you look at the construction of a window today, it’s rather complex, and for this reason a lot of architects delegate these issues to specialists like engineers, façade planners, and so on. We have catalogues and norms, we’re used to working with a more or less fixed assortment, but now that we have the digital technologies that allow us to do customized elements, it would be interesting to consider whether we can make windows with specific qualities to fulfil particular needs. Perhaps it could be a good field of investigation for your research, Momoyo, to think about doing customized solutions.

MK: Yes, originally the window was a very local product, closely linked to a specific site and people, but the advent of industrialization transformed the production process, increased the scale. Today we also have to factor in concerns like climate change, which is a challenge when we think about the future of the window. Switzerland has numerous small window manufacturers, so there is the potential here to produce specific windows for different areas—to innovate in response to changing needs. But speaking of innovations, I’d like Andrea to talk a bit about the New Monte Rosa Hut, which is a very beautiful project as well as a challenging one. Switzerland has a long history of building mountain huts that allow people to inhabit extreme environments, at least for a while. As a building type, it offers an interesting platform to think about the possibilities of the window and its relation to technology.

-

New Monte Rosa Hut, Switzerland (2009) by Bearth & Deplazes with Studio Monte Rosa ETH Zurich © Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

AD: I’m still very proud of the work of the students who carried out the Monte Rosa project. We had the Swiss Alpine Club as our client and ETH Zurich. There was an interesting tension between the two: ETH was always pushing for innovation, looking to test solutions for the future, whereas the Swiss Alpine Club was risk-averse, wanting a more traditional approach, and our students were caught in the middle. It was a fantastic group of master’s students who worked for over two years, developing the project to a point where it was possible to build it. One of the key moments concerned the design of the staircase. We had a circular plan, and the students proposed to put the vertical circulation along and around the external wall, as a spiral movement upwards. The window lighting the staircase leads from the entrance up through the six floors of the building, moving through 360 degrees. So the window accompanies you as you climb up the stairs, offering a wonderful panoramic view: starting in the east, then moving to the south, to the twin peaks of Castor and Pollux, and finally west to the Matterhorn. The engineers of the Swiss Alpine Club asked “Why isn’t the staircase at the centre of the ground-floor plan, with all the rooms set around it? This is no good.” But the students said, no, you don’t understand the solution. The band of windows, with the sun shining on it, is also the source of passive heating for the whole building. The warm air rises up though the hut, and there’s a ventilation system that brings the warm air down to a heat exchanger that provides warm water for the shower and whatever else is needed. It works so well: sometimes the warden even has to open the windows to let out the excess heat. The students understood that a window is more than only one thing, and they had fun working with this: they even had the band of windows crossing the photovoltaic shield on the façade. In the end the SAC engineers had to admit that the students were right and this was the better solution.

One press review of the building described it as a crystal, but it’s interesting that the students never spoke about it in those terms. During the design process they always talked about something like a refuge, or a medieval cell, a place to shelter if the weather is bad. So the building is like a contemporary version of that, with small windows—simple Veluxes—that bring light to the bedrooms. The placement of these windows responds to the different heights of the bunkbeds, which explains why there’s no regular pattern with clear floor heights on the external façade. On the other hand, the band window was produced in collaboration with another window manufacturer who really understood what the students wanted to achieve, and was very motivated by them to look for the best profiles and connections to devise the best product. It was fantastic to see the student engagement to push for this solution.

-

New Monte Rosa Hut, Switzerland (2009) by Bearth & Deplazes with Studio Monte Rosa ETH Zurich © Juan Rodriguez

-

New Monte Rosa Hut, Switzerland (2009) by Bearth & Deplazes with Studio Monte Rosa ETH Zurich © Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

-

New Monte Rosa Hut, Switzerland (2009) by Bearth & Deplazes with Studio Monte Rosa ETH Zurich © Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

MK: That’s very beautiful.

LS: There’s one remaining question that we should engage with: What is the quintessential window for you?

MK: There’s a very beautiful village called Bise right by the seashore in Okinawa which has the most surprising windows I have ever encountered. The houses are in a very specific style: single-storey constructions, around eight by eight metres in plan, that are raised from the ground and covered by a roof that is supported by columns. The houses are surrounded by a beautiful green hedge—a windbreak of fukugi trees, three or four metres high. That’s all, nothing else is added, but there’s a particular quality of depth to the windows here—it’s as if the windows were the garden and the green hedge itself, as if nature and the house had merged into one space.

AD: It’s like the sublimation of the window.

MK: Yes, the window that becomes landscape. I’d like to make a window like that myself one day.

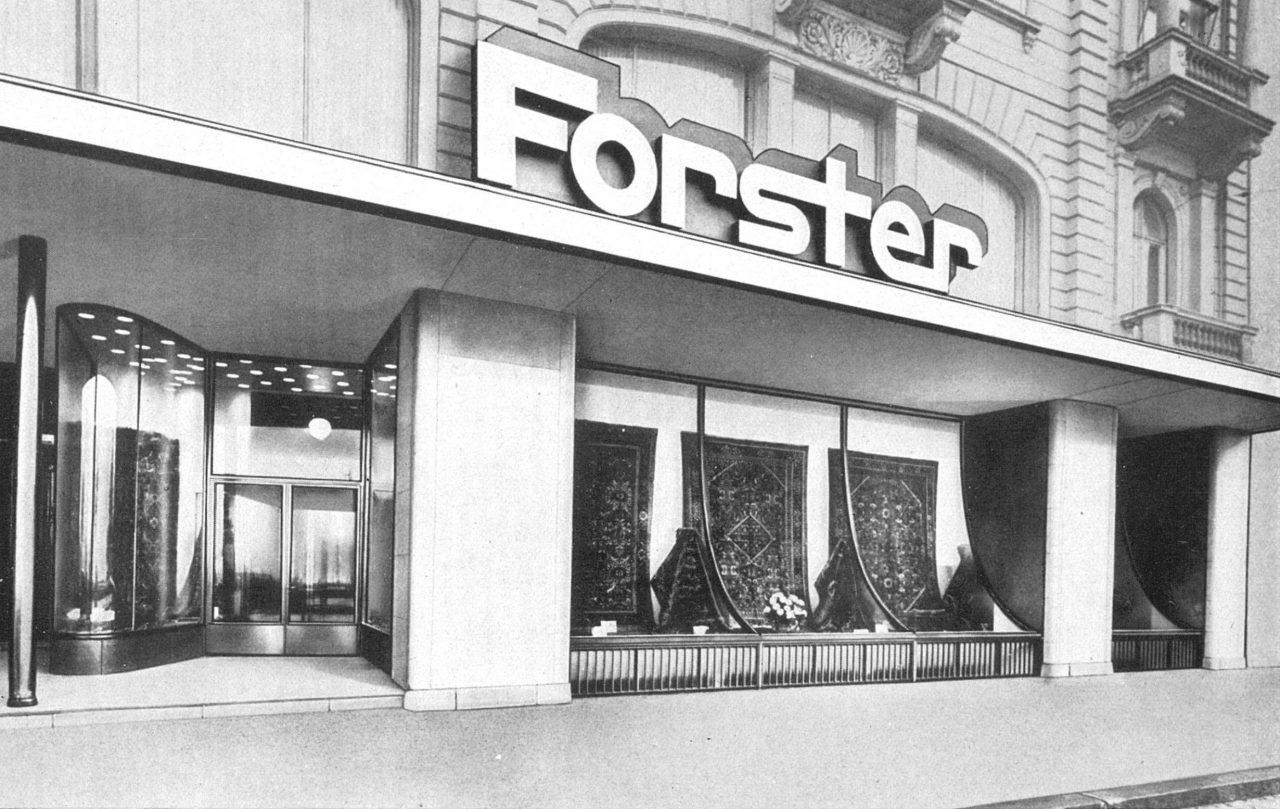

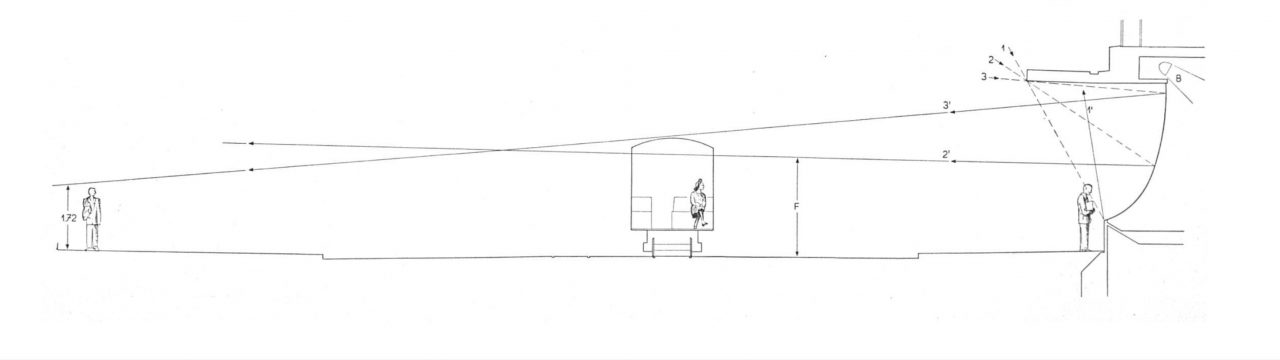

LS: I would offer an example that is in some ways the opposite, a window that was developed here in Zurich for a shop (Forster carpet store) in Bellevue in the 1920s. One of our students did some wonderful research on it. It’s a shop window designed to avoid reflections, so the glass is not flat but curved in the vertical. It’s a window that enables multiple things at the same time, beautifully illuminating several dimensions—formal and spatial—of what a window can be: it allows passers-by to see the products, but also brings light to the lower floor. As a surface it protects the interior from rain and wind, as a space it acts as a showcase. It’s about glass, about vision, about light, and about the question of airflow as well, because you need a system for the air to go out. And while the opening that Momoyo just described is about dissolving the limits, making it into a threshold, this one does the same but in a very modern way. And perhaps the advantage of the modern window—for a historian, at least—is that it allows for a very clear analysis and understanding of what the window can be.

-

Shop window in Zurich, Swizerland (source: Das Werk, Band 34 1947, Heft 12)

-

Section through the street and the shop window (source: Das Werk, Band 34 1947, Heft 12)

AD: So you mean that the window is also about space as well.

LS: Yes, for sure.

AD: And this is exactly what I’m interested in. I would say that a window could be more than just a plane, a surface. It could itself become something like a space in between inside and outside. I’m interested in thinking in this direction.

-

(From left) Andrea Deplazes, Momoyo Kaijima, Laurent Stalder at Never Stop Reading bookshop

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at Switzerland’s Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. A lecturer at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba from 2000 to 2009, an associate professor from 2009 to 2022, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), Columbia University (2017), and Yale University (2023). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city, the suburbs, and agricultural, mountain, and fishing villages through publications such as Made in Tokyo, Pet Architecture, and Commonalities. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia. In 2022, she was awarded the Wolf Prize for Architecture.

Andrea Deplazes

Andrea Deplazes was born in 1960, in Chur, Switzerland. From 1982 to 1988, he studied architecture at the ETH Zürich, where he received his diploma under the guidance of Prof. Fabio Reinhart.

In 1996, he became member of the BSA (Bund Schweizer Architekten). From 1997 to 2001, he was selected as assistant professor at D-ARCH, ETH Zürich. In 2001, he co-founded Bearth & Deplazes Architects plc., located in Chur and Zürich, with Valentin Bearth and Daniel Ladner. The following year, in 2002, he was appointed as a regular professor for architecture + construction at D-ARCH, ETH Zürich. Prof. Deplazes launched the concept phase of the New Monte Rosa Hut from 2003 to 2005 as part of the ETH-Studio Monte Rosa. He then served as Dean of faculty D-ARCH, ETH Zürich from 2005 to 2007 and continued in this role from 2008 to 2010. From 2007 to 2009, he worked on the implementation of the New Monte Rosa Hut with Bearth & Deplazes Architects plc.

Laurent Stalder

Laurent Stalder is professor of architectural theory at the ETH Zurich. The main focus of Laurent Stalder’s research and publications is the history and theory of architecture from the 19th to the 21st centuries where it intersects with the history of technology. His most recent publications are: “Architektur Ethnographie” (Arch+, 2020), Un dessin n’est pas un plan (Caryatides, 2023), On Arrows (MIT Press, 2025).

Top image: New Monte Rosa Hut, Switzerland (2009) by Bearth & Deplazes with Studio Monte Rosa ETH Zurich © Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Silke Langenberg

25 Jul 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with François Charbonnet (Made in)

25 Jan 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Christine Binswanger, Raúl Mera (Herzog & de Meuron)

24 May 2023

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Conversation with EMI Architekten

15 Dec 2022