Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Taiwan

This issue, I’d like to introduce a park that I designed myself.

Jiaoxi, Yilan’s Paomagudao Park, completed in 2021, was formerly the Mingde Training Class, built as a training school (quarters) for the Taiwanese army. It was used as a place for “military education” and “anti-communist thought training” beginning in the 1950s, when Taiwan was under martial law, but fell into disuse about twenty years ago with the 1987 lifting of martial law and the changing circumstances of the country. It then remained in the town as a relic of a dark past.

The town of Jiaoxi is in the northern portion of the Lanyang Plain, a delta that shapes Yilan County. Mountains press against its back, and the ocean is only fifteen minutes away by car. It was originally populated by aboriginal people, but it seems that many Han Chinese immigrated to it during the Qing dynasty. Hot springs were dug there under Japanese rule, and it now bustles with tourists every weekend as a spa town an hour away from Taipei by car. It was about a thirty minute drive away when I lived there, and I’d come to soak in its aged hot springs almost every week during the winter.

-

Paomagudao Park. An empty field sitting in of a town lined with buildings, a mountain at its back. (Photo: Ching-Han Hsieh)

The site of the former training center sat abandoned in the middle of Jiaoxi for a long while. The large open plot of 5.7 hectares within the dense tourist destination that only continued to add new hotels and restaurants was surrounded by a wall, made distant from everyday life.

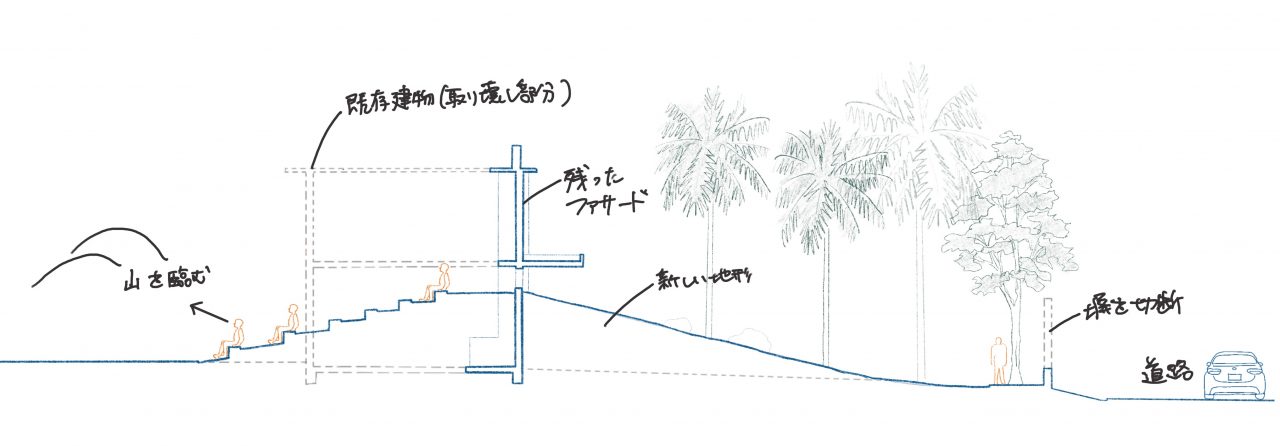

I took part in the project to make this land “just sitting there” into a park open to the public while at Fieldoffice Architects. I was involved in the process from the design competition stages to the creation of its working design, and I was partially responsible for supervising progress on-site. Work on the project could be split roughly into two methods. One involved not creating any new structures and demolishing the twenty or so commonplace concrete army buildings that still remained, or partially demolishing them (downsizing), changing it into a park space through subtractive efforts. This was done to make use of the potential of an empty lot within a dense city, as well as a way to connect the closed-off buildings dotted with windows.

Many trees that have now grown tall still remain on the site. These were planted along the various buildings when it was used as a military facility in order to hide the buildings. In the process of downsizing, many of the structures were turned into semi-enclosed gazebos of sorts, but simply removing their old sashes was enough to completely change how these trees looked. Looking out from the windows that have become simple holes, one can see just how important their glass and frames were. To further connect the buildings, openings were created using subtractive methods such as opening them up by leaving only posts and beams around footpaths, presenting even more views of the surrounding trees. By going further and removing their roofs, the formerly unseen treetops now showed their faces, creating utterly new sights. The conditions of these buildings as preexisting military facilities come into view by opening holes into them. These freely created horizontal and vertical openings capture the plot’s vegetation, blurring the lines between landscape and architecture.

In parts, not just the roof but even the midsection and above of a building is entirely removed. By intentionally making a cut mid-way into an existing window, the rhythm of the windows’ regular intervals is preserved as benches where visitors can sit. Then, to match this rhythm, holes have been opened in the floor slab where vegetation has been planted. By doing this, windows of a kind that connect the environment with interior spaces are even made in the floor.

-

The rhythm of the former windows become benches, while plants grow from holes opened in the floor. (Photo: Chun-Cheng Yeh)

The other design method took place on a somewhat larger scale. Through the insertion of rolling terrain, a sense of directionality and place was given to the formerly flat site. In general, this involved creating large areas of sloped terrain where people can sit facing the large mountains just behind the area, and this applied to the existing structures as well. The rubble from the disassembled buildings is buried under this terrain.

The mountains are close to this town, but people here had begun to stop taking notice of them because of the jumble of tall hotels and more that came with its development as a spa town. Like windows that frame the scenery, this terrain has an effect on our attitude, acting as a device to show us the scenery.

The wall along the street that long separated this site from the town was also partially severed like the other structures in order to make it more visually open. By leaving only the façade of the most conspicuous two-story building facing the road while adding to it the new terrain, the noise of the street is blocked off while creating a quiet performance space behind it. The terrain also acts as special front-row seating with the mountains just before your eyes.

All of these actions make the park into an uncanny place. Perhaps the design was not one of making ruins new and beautiful, but one that ruined it further instead in a sort of process of returning it to nature. This process turned windows into holes or spaces, opening the buildings up to the outside world. It framed countless mountain, tree, and geographical landscapes as scenery, ultimately allowing them to enter inside.

By once again understanding windows as sudden openings in closed spaces, perhaps we can say that the very act of turning this place into a park was a way of opening a window in the town. It is a blank space where the people can come to a stop in town and stand still, as if they were taking a pause to look out a window.

-

Looking out at the mountain. Its foot is framed by a span-wide opening made in the structure in front of it. (Photo: Chun-Cheng Yeh)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 16: Red Bricks and Bullet Holes : The Kinmen Islands (Part 1)

18 Dec 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 15: The Folk Spirit Dwelling Within Decorative Window Grilles

22 Jul 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024