Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Zhangcun: The Needs of the Underground Part 2

05 Jan 2017

I’ve come to realize that meeting with elders is the best way to learn about their village. Walking through a loess land of beautiful green trees, I continued to develop this method I’ve worked on throughout my journeys. Suddenly I came upon an older woman putting a handkerchief on her head while resting in the shade of a tree.

Does she live in a yaodong? Either way, I tried to communicate to her that I’m interested in architecture by showing my sketches. Naturally, I could hardly communicate with her in Chinese.

It seems I managed to get my intention across after a few minutes of struggling. She took me to her nearby yaodong, indeed her place of residence. There was a small hole serving as entrance to her underground cave located some distance away from a square hole in a courtyard. Because she had a bad knee, she guided me to her dwelling while leaning on a walking cane.

-

Approach yaodong

My image of a “house” continued to change as I walked down the maze-like entrance carved out of rough ground.

Her yaodong was about 6m in depth. I suspect this is standard: every yaodong I encountered had a similar depth. Caves were constructed with three sides facing a courtyard full with tall trees. The remaining side is a bare cliff.

-

Her yaodong

Can we actually say “construction” when referring to such a dwelling? To create such a space from nothing, how many people and how much time was devoted to this project and how much soil was hauled away? Building supplies are virtually unlimited. But, precisely because of its plentitude, it may be more appropriate to say that there are no building materials.

Some surfaces of the wall remain bare, but most are reinforced with sundried brick. Loesses are quite solid but weaken when they become wet. The courtyard is also beautifully finished with adobes as well.

The old woman seems to live in this yaodong alone. There are some rooms that are no longer used. She showed me her main room.

-

The old woman and the main room of her yaodong

Two windows and a single door adorn the main entrance consisting of a pointed arch made of sun-dried bricks. Embedded in those windows is a wood lattice fringed with black burned bricks.

-

Inside her main room

Upon entering the room, which has about 7m in depth, it is extremely dark. However, there are walls to the left, right, and behind me, which makes me feel quite secure. Here, too, paper was attached to the inner walls of this room. Sitting on her bed, the old women curiously watched me as I became obsessed with measuring the room. Noticing that my measuring tape was broken, she gave me a small one.

I didn’t notice from the outside, but there is also a small hole located at the top of the arch. TV cables and other wires are run through this hole. This means that in addition to air and lighting, they get their electricity from the entrance as well. I realized just how important such contact with the outside world is for them.

-

A window lined with black burned bricks. The surrounding wall is reinforced by loess with straws.

Leaving the dwelling of this old woman and her handkerchief, I head up the dirt where there were numerous old people. They appear to have a good amount of free time. Seated in the middle of them, we spoke endlessly. Maybe because this is the countryside, their language didn’t sound like Chinese to me. Through written communication I could discern that only two out of these nine old people still live in a yaodong. The remaining seven began moving to a new home (xīn fáng zi) – a brick house on the ground –about 20 years ago. When I asked about their reasons for leaving the yaodong, they said that living in such a cave put pressure on their knees and its humidity.

-

They use yaodong as storage and "build" small new houses on the ground.

While talking to another old man still living in a yaodong, I was surprised to learn that he was 100 years old! I wondered how old the yaodong in this village were. I asked him, and his response was 2,000 years old.

I might understand if he was referring to the age of the village, but I’m not sure this yaodong could be that old…

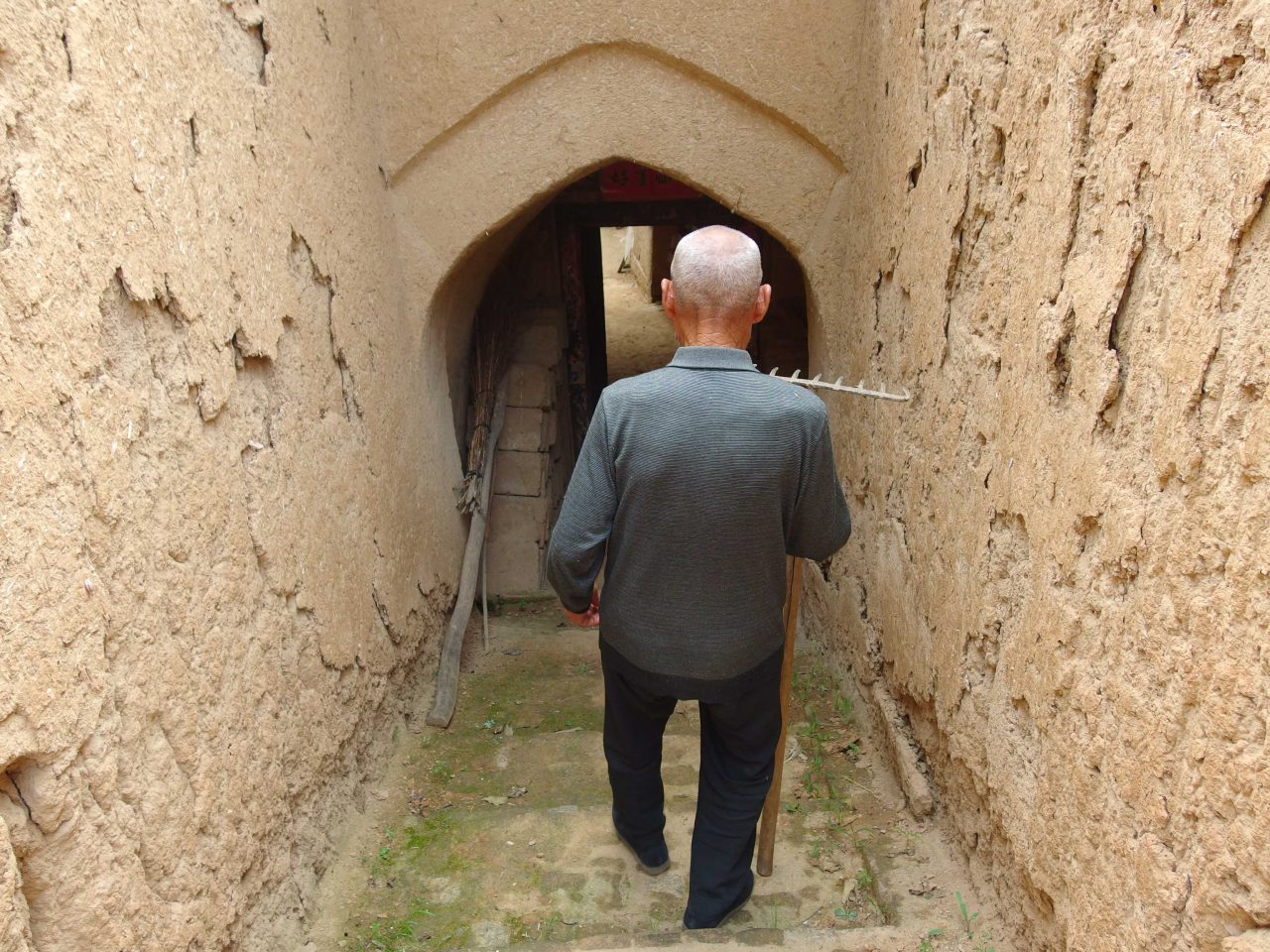

Pondering his answer, I followed the 100 year old man using his hoe as a cane.

-

Guided by a 100 year old man

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.