Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Taiwan

Democracy and freedom have now spread throughout Taiwan, a place where freedom was once heavily restricted. This is something one can feel even in their daily life. The people of Taiwan are unusually tolerant, and there is a sense that generally speaking, anyone may do anything anywhere. This freedom was thoroughly present even at Fieldoffice Architects, where I once worked. From my first day there as an intern, I was instantly drawn in by the office’s atmosphere of anyone being able to give their opinion.

They even take this approach and express it in public spaces they create in reality. How many spaces are there in the city where people can be free? In the provincial city of Yilan, Fieldoffice makes spaces that can be taken as an answer, or even a challenge to this question.

Fieldoffice has been involved in public projects both large and small in Yilan for about thirty years, and they value the creation of blankness within cities. In Yilan, such empty spaces are frequently realized in the form of canopies.

Take, for example, Diu Diu Dang Forest Park (2006), located in front of Yilan Station. Efforts were made to redevelop an important corner in front of the station that still made use of brick construction from the period of Japanese control, intending to place a building on the site and match its surroundings. A proposal was then made to keep the construction in place and reuse the space as a public café while building a fifteen-meter-high canopy covering it all, preserving this station-front space and its banyan trees for the sake of the public.

-

Diu-Diu-Dang Forest Park, where a market is opened what feels like every weekend. The single-story structure seen in the back is a building from the period of Japanese control.

The plaza is used in a variety of ways. A market is held here nearly every weekend where men and women both young and old can be found buying, selling, singing, and dancing. One is quick to forget that they are standing under a canopy for whatever reason, perhaps thanks to it being tall and transparent. The area remains open at night, and the public is free to come and go at any hour to meet, have fun, and debate. It provides a truly indispensable foundation for democracy. The towering steel frame may appear at first to be excessively designed, but this is part of a strategy to extend the lifespan of this place’s emptiness for as long as possible by creating somewhere that is “hard to destroy,” anticipating the public’s critical view toward simple proposals to destroy something that the government has already built. Looking around, you can see one open space after the next being turned into commercial buildings, leaving this space alone sitting there, vacant. Considering how frequently it is used by the people, it’s hard to imagine this emptiness disappearing any time soon. I myself would sometimes come here at night and eat douhua (a Taiwanese sweet) sold at an auntie’s store under the canopy.

I was at the office for a little less than seven years, and during that time I too had the opportunity to take part in canopy designs. In the hot spring town of Jiaoxi, located in northern Yilan County, buildings on both sides of a street in front of a Taoist temple were destroyed in order to restore an open plaza that once existed in the area. As emptiness also brings about temporal freedom, the public now determines how this restored stage for religious services placed under a canopy is used. The vast majority of Yilan Transfer Station, a bus terminal which opened last year, is located under a semi-outdoor canopy, making it a place that welcomes travelers of all sizes, whether bicycles, cars, pedestrians, or buses.

These spaces under open-air roofs were, to begin with, essential in Yilan, a place where it rains for about half of the year. They are cool spaces where the wind can blow through while keeping people dry and out of the sun’s powerful rays. The sides of the waterways in Yilan’s agricultural regions are also dotted with small canopies used by farmers to wash scallions. One can draw a throughline between these and the open-air pavilions (涼亭, liángtíng) built by the Tao people on Orchid Island, and they are a kind of archetypal image in Asian monsoon climates. It’s little wonder that the public so readily accepts canopies. Incidentally, these scallion huts are apparently not privately owned, but are maintained by farmers in the area. They’re tenacious, as even if one is destroyed in a typhoon (and they do in fact get blown away from time to time), it’s rebuilt in no time. One can even cool off under them on a hot summer day while soaking their feet in the water.

-

An older man and woman washing scallions under a simple canopy

The project that took these canopies to the largest extreme is the Luodong Cultural Working House (1999-2014) located in south Yilan’s Luodong. From the first time I visited it in 2015 to now, I have never been more shocked by contemporary architecture than I was by this canopy. This extraordinary structure is just that beyond the bounds of understanding.

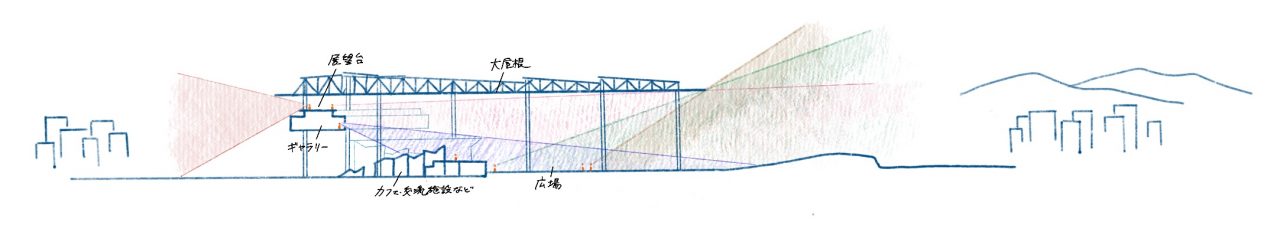

What stands out most is its size, and its height. A simple canopy 18 meters (59 feet) in height, 90 meters (295 feet) in length, and 54 meters (177 feet) in width stands here like one of the formerly mentioned scallion huts made gigantic. A stage, a space for socialization, a café and more are located in the plaza under it as a gallery floats in the air, all of their lines of motion intersecting. The grounds also contain an athletic field, a pond, and more, accepting people from any and every angle.

As always, the people freely gather here at all times of the day. Old ladies performing a strange dance, children skating, old men napping, parents playing badminton, people holding a picture book reading, youths performing street dance, Covid vaccinations being given out…you can do anything here. They say that the nearby middle school would sometimes have gym class here on rainy days. There’s a freedom in the way that all of these activities coexist with one another while establishing their own quiet boundaries. I still vividly remember the words of a Japanese architect who once came to see this place: “The Taiwanese are good at using space. The Japanese won’t start using it without getting permission first, but it’s like the Taiwanese use it first, then stop if someone gets mad.”

Being under this roof also makes me feel a kind of excitement in my heart that I don’t normally have in my daily life. I can only describe it as the sensation of the power imposed upon us by the large. The roof is too high up to create a sense of oppression, but it so clearly exists above me. Clouds may give me the closest sensation to this, yet here there’s a power coming from its distinct rectangular shape. This place is made into something special by the ground, columns, and roof as they come together to clip the surrounding scenery into unique frames. This framing created by simple straight lines is like a window opened in the city, confirming one’s own location by relativizing both the mountains and the streets.

If you walk up to the floating gallery, you’ll find that its long corridor, which makes full use of its length, creates a different kind of framing by way of the height of its windows. Sit in one of the chairs placed in the hallway and look down on the plaza from one of the windows that seems to invite you to do so, and the canopy is nowhere to be seen. It’s a way of making you momentarily forget the expanse around you so you can focus on the gallery.

Climb up to the roof of the gallery and next you’ll find that the canopy, something quite distant all this time, is now so close that it feels as if you could reach out and touch it. Yet the power of its straight lines tears through your field of vision to a nearly violent degree. It’s a strange roof, distant yet close, intimate yet wild. Look down on the plaza from here and you can see people moving about at a striking angle, like a drone watching from overhead. You’re close enough to just make out everyone’s individual expression, giving a strong feeling of how alive they are. One of the reasons this place is so loved by the people must be this opportunity it gives them to leave the surface and get a bird’s-eye view.

-

The observation deck atop the gallery. The roof feels close enough to touch.

-

Profile diagram of the Luodong Cultural Working House. The city is framed by its size and height.

-

Looking down on the plaza from the gallery roof.

This Cultural Working House actually took a total of fifteen years to complete. The canopy, gallery, and surface-level facilities are structurally independent so that it could be built in stages, regardless of the changes in government that occurred during its construction. These various places were created over a long period of time in spite of, or rather, because of the pauses in construction, giving rise to its shape today.

An unusually large roof that relativizes one’s own town and the surrounding environment. A gallery that at times makes one forget about the roof, then brings one closer to it at others. Framing that manipulates size and height to make possible the coexistence of many different activities and points of view. Today, as always, people gather and meet under the canopy, the wind carrying away what takes place there. I imagine that this city’s democracy will only continue to grow over time atop this foundation.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 16: Red Bricks and Bullet Holes : The Kinmen Islands (Part 1)

18 Dec 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 15: The Folk Spirit Dwelling Within Decorative Window Grilles

22 Jul 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024