Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Taiwan

It’s said that Christians now constitute around 7% of Taiwan’s population, a rather high proportion compared to Japan’s stated rate of around 1%. Though neighboring countries, their religious situations are quite different. Christianity on this island can be traced back to the early 17th century, as the Age of Discovery was nearing its end, when the Dutch and Spanish began colonizing Taiwan. It first spread mostly in southern cities such as Kaohsiung, Pingtung, and Tainan. Taiwan’s oldest standing Catholic church, located in Pingtung (Wanjin Catholic Church), was rebuilt in 1870, and even now the towering brick church seems like a foreign presence within the city.

In contrast, colonial administration had trouble making inroads to the eastern coast of Taiwan, where many indigenous people live, due to its confined and inaccessible land. This also meant that foreign cultures were slow to enter into the area. Now, though, there are many Christians among the indigenous people of Taiwan, including a number of my acquaintances who frequently attended services and Mass. When I visited China’s Loess Plateau in the past, I was shocked to see that most of its residents had crosses in their homes, and I felt a similar sense of surprise regarding the indigenous people concentrated in Taiwan’s eastern coast. I assumed that being indigenous meant having one’s own traditional faith and celebrations that belong to your people, unlike world religions. It seems, though, that the world is not that simple of a place. In reality, these indigenous people’s lives involve a coexistence of Christian and native religion and culture.

Many indigenous people, primarily the Amis and the Puyuma, live in Taitung, a county full of churches. Taiwan’s complexity is illustrated well by the existence of modern and contemporary Christian churches on its eastern coast primarily meant for indigenous people. Of these, I’d like to introduce two churches I visited one summer.

-

Bethlehem Mission Society Headquarters (Designed by Father Karl Freuler)

When freedom of religion was restricted on the Chinese mainland in 1949, many Catholic orders located there moved their headquarters to Taiwan. The priests of the Bethlehem Mission Society, a Swiss Catholic order, moved to Taitung in 1953. They have a history in contributing to the area’s modernization as they worked their way into the daily lives of its indigenous people and spread Catholicism through their charitable work (though some conflict must have arisen as well). While missionaries from other orders did come to Taitung, the Bethlehem Mission Society was notable in the way they built schools, hospitals, kindergartens, and retirement homes, along with their assistance in the indigenous people’s economic independence and their missionary work carried out while still respecting traditional ways of life. They were also the ones to create an Amis language translation of the New Testament.

The Bethlehem Mission Society built many churches in Taitung beginning in the 1950s. Some were designed by architects brought from Switzerland, while others were designed by its priests themselves. Father Karl Freuler designed the Bethlehem Mission Society Headquarters in 1966, which is configured like a reinforced concrete monastery with an inner courtyard encircled by a refectory, church, offices, exhibition rooms, and more. While it appears to be a piece of simple modern architecture, the deep shadows cast by the Chinese banyan and palm trees growing inside the courtyard and around the area give it a very Taiwanese appearance, and the entirety of the structure cannot be seen at once. Immediately after entering inside, an open loggia that believers use to access the church stretches northward toward the courtyard.

-

The courtyard and loggia of the Bethlehem Mission Society. The entrance to the church is in the rear.

Looking into the church through its wooden doors, I could see green-tinted, cream-colored light faintly entering in from the windows. The church is a long symmetrical rectangle, with powerful deep lattice beams. On the left and right (south and north), milky-white acrylic boarded fittings placed into slim blue iron sashes cleanly fill the space between pillars. These apertures are divided into top and bottom sections, with pivoting windows at the top and hinged doors at the bottom. I could imagine a comfortable breeze passing through the church whenever these were fully opened. I found it interesting that the light entering from these north and south apertures took on two completely different colors. Looking out the south window, I could see a large shadow cast by a brise-soleil made from wall pillars and horizontal panels. The deeply recessed building must have been designed this way in response to Taitung’s environment, with its intense sunlight. Once filtered through trees, eaves, and acrylic boards, this sunlight becomes something easy on the eyes that illuminates believers.

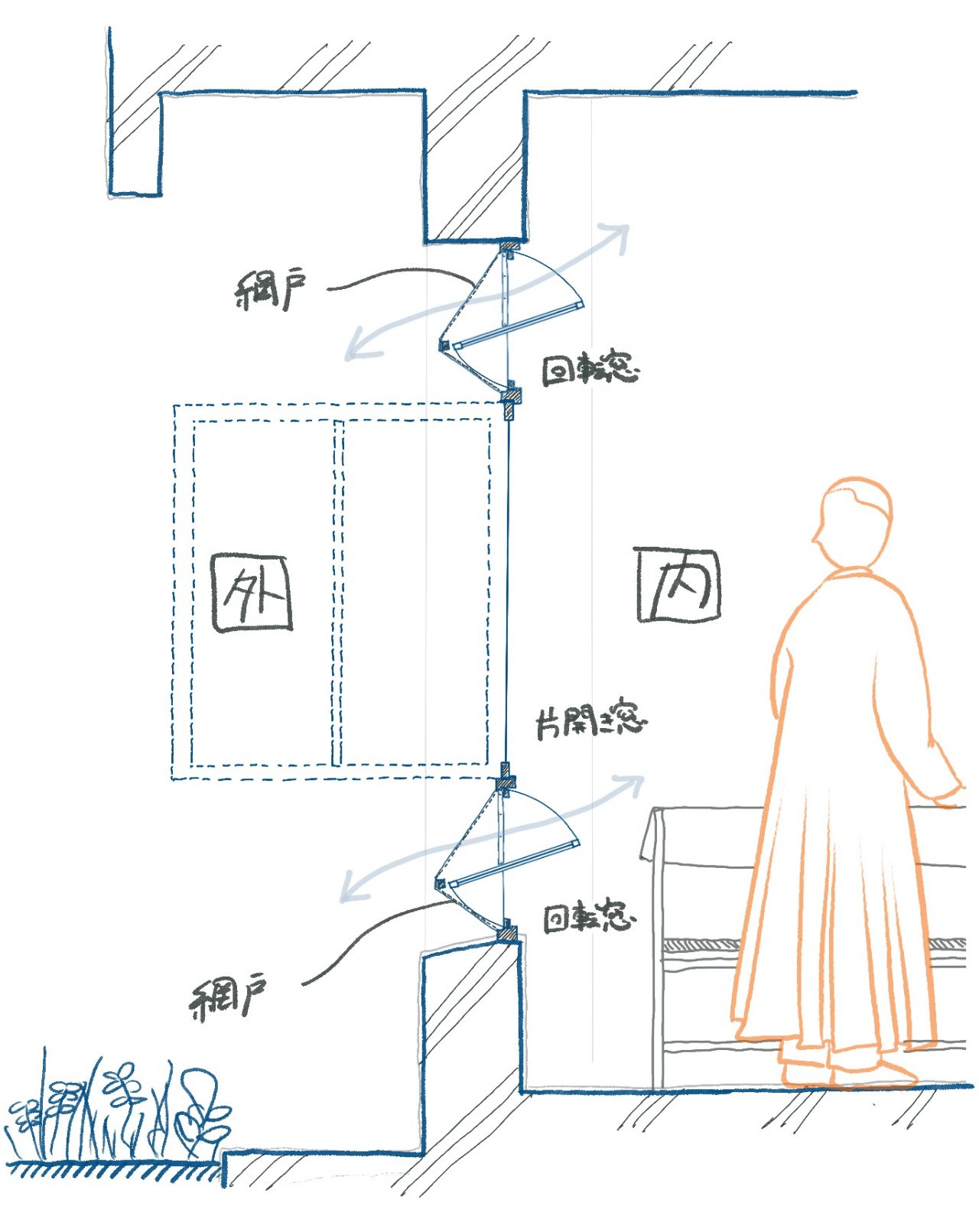

While we can find chairs, tables, shelves, prie-dieu, and more made from wood inside the church, it’s said that all of these furnishings were created by students at a woodworking school founded by the Bethlehem Mission Society. I also saw intricately handmade wooden sashes in the refectory. Its screen doors are fixed in place along the open position for its pivoted windows in order to prevent bugs from entering inside, a necessary feature for any cafeteria. While simple, it is a logical decision that provides a human touch to its otherwise proper and exact architecture. Even in a modern, post-and-beam, reinforced concrete church that is both laconic and economical, the way that its window areas bring in light and wind present a clear depiction of consideration given to the local environment. Perhaps a connection can be drawn between this thoughtfulness and the attitude taken by the Bethlehem Mission Society in its missionary work.

-

Cross section of the refectory’s pivoted windows

The St. Nicolaus Church is a defining work of the priest and architect Felder Julius, who lived in Taitung for 40 years beginning in 1965. The church’s roof is lower than the shore’s palm trees, and it sits closely nestled in its village. The church has a regular heptagonal shape with a compositional focus on its center so as to direct the most attention of all to its altar. Its interior walls are also slanted in order to point as many of its gathered indigenous people’s ears to the words of the priests. Buttresses support the heptagon in order to create a pillarless space, and clerestory windows are placed in the gaps of its light reinforced concrete roof, faintly illuminating the altar. I imagine this space that merges structure, sound, and light played a major role in the local missionary work carried out here. Even now, it is a fresh and charming small church.

Though said to once number over thirty, there are now only five or six Bethlehem Mission Society priests. Still, these now-aged men live under the subtropical sun here while respected by the people. I cannot imagine the struggles and efforts of these Swiss priests who came to the east coast of Taiwan almost by accident during a time of changing affairs in China and the world. They lived with both a religious mission while also trying to support the very lives of the people they met, and their legacy continues to live on in this place by way of a number of small churches still in use today.

The sun began to set in the village as I gazed at the church. An Amis boy wearing swimming trunks came to the church’s garbage dump, sent by his family. This little church is now just another part of the scenery in the life of the village.

-

An Amis boy who had come to the church’s garbage dump

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Cultureʼs overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 16: Red Bricks and Bullet Holes : The Kinmen Islands (Part 1)

18 Dec 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 15: The Folk Spirit Dwelling Within Decorative Window Grilles

22 Jul 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024