Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Houses beyond the Places of Scenic Beauty (1)

05 Oct 2016

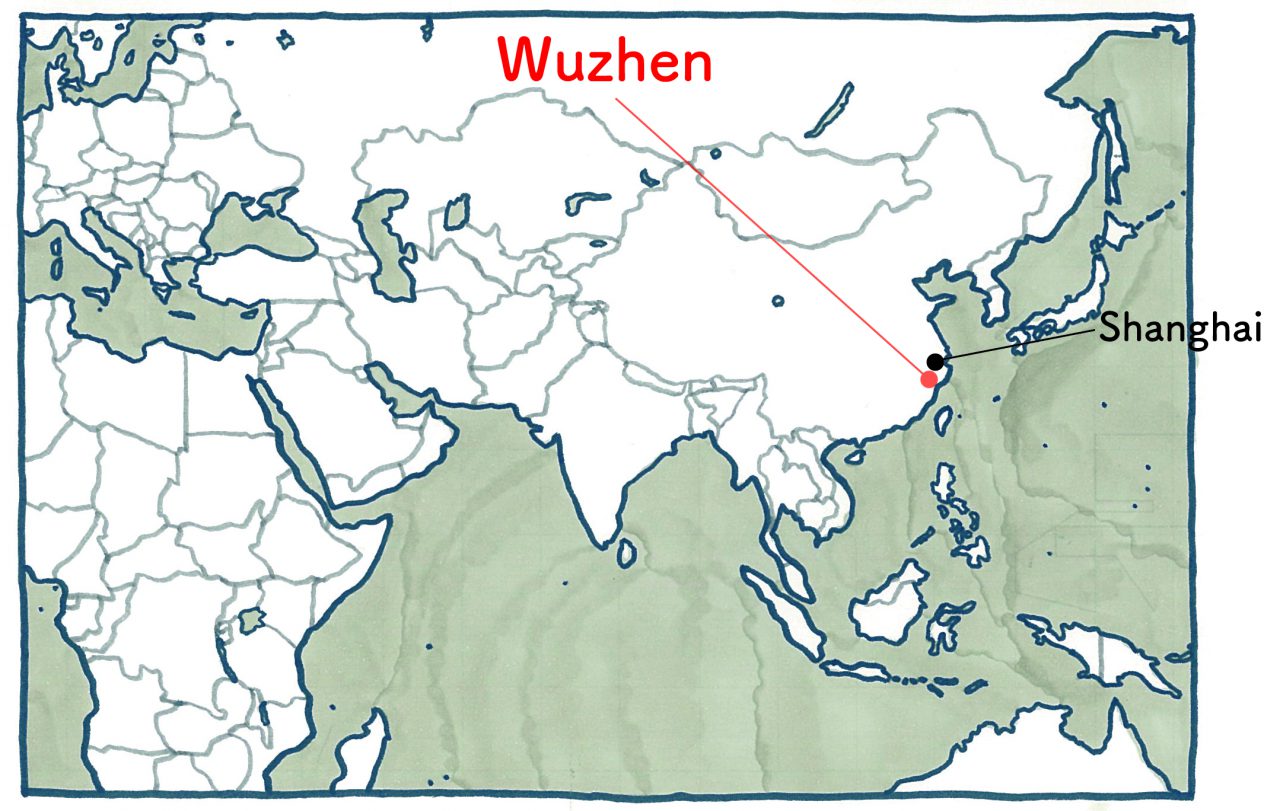

We arrive at the town of Wuzhen in northern Zhejiang after a two-hour bus ride from Shanghai. This is an area famous for its beautiful riverside district. Wuzhen is located near the Yangtze River Delta, an area known for its many contributions to ancient Chinese civilization. Given its geography there are not many hills to speak of, rivers flow in every direction, and there are still many riverside settlements. Lost in a sea of Chinese tourists, I, too, was headed to Wuzhen, the “Venice of Asia”.

With its 1,300 year history, the area of Wuzhen is divided into the cardinal directions by rivers that run in the shape of a cross. The east and west side of the city is maintained by the government and referred to as a place of scenic beauty. It is brimming with people. The place I went was located on the west side of this tourist spot, Xishan. It is said that its former inhabitants relocated to newly built houses nearby with restaurants and lodgings now occupying the deserted village. It’s difficult to judge the merits or demerits of such an approach presumably rooted in political policy. Either way, the houses did not do anything wrong.

-

The Scenery of Xishan, Wuzhen. Former inhabitants have moved away, and only their houses remain.

It’s said that these houses have been here since the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Since the Ming Dynasty extends back to the 17th century we can imagine there are some pretty old buildings still in existence. Since many buildings jut out over water and stone foundations seem to make them float, it makes senses that people would refer to this place as Venice—of course, water taxis are also coming and going. The buildings seem to be constructed in the timber framework method with gaps filled with black bricks called sen, all coming together to form the walls of the houses. The riverfront walls are all wooden, including fittings such as doors. Tourists view the river from inside these houses and envision life on the riverside. It’s hard to imagine that up until dozen years ago people lived in these houses.

Walls of stacked brick marking the border between neighboring houses are painted with white plaster. These walls are strikingly similar to the small firewalls of Japanese architecture, udatsu. Their wooden doors and windows are each adorned with different kinds of fretwork. I imagine each one has its own meaning, though we will never know about it—no one is living there.

-

Exterior walls full of windows and doors with fretwork.

-

The characteristic piling of black bricks and many-layered tiles.

The walls of stacked penetrating black bricks and the nearly excessively layered tiles were, of course, interesting from the standpoint of design, but I wanted to see how people live today. I left this scenic area. I wondered what sort of houses people live in outside of the area. There must be former inhabitants of Xishan living nearby.

Just outside of the scenic area are densely built three-story housing complexes located along a wide road. The first floor seems to consist mainly of shops while people live on the second and third floors. This seems to be the modern-day townscape of Wuzhen. The former wooden doors and windows are replaced by an aluminum sash, and identical doors and windows line the street.

-

Just outside of the scenic area are densely built three-story housing complexes.

I was able to determine that the structure of many buildings is a reinforced concrete frame with a brick wall because many were still under construction. In essence, it seems not all that different from the old riverside houses with a timber framework and black brick walls. Interestingly, the firewall is still present as mere architectural decoration.

-

New housing with reinforced concrete frames and brick walls. The firewall is used only as decoration.

Behind these buildings are a small number of trees lining the riverside; here people hang their laundry out to dry, and shops use this place as a storage area. Walking through this chaotic landscape, you will see middle-aged women playing mah-jongg in broad daylight. Knowing that just across the river was the scenic area overflowing with tourists made the scene all the more interesting. However, I couldn’t find anyone who used to live on the riverside.

-

Riverside scenery.

Aside from those three-story buildings were a lot of people living in the space beyond the scenic area. Because there are no foreigners like me walking around this district, an old man spoke to me. Nothing in his hands, this small old man in a loose white shirt eagerly spoke to me with a smile. He seemed to live around here, but having come to China just a few days ago I didn’t have any idea what he was saying. Despite the inability to communicate I thought this might be a chance to see the life of locals and followed him. I tried to communicate with him in the handful of Chinese vocabulary I learned. It was at this time I learned that showing my sketches is also an effective means of communicating with locals. I was able to convey to them that I’m a person interested in architecture. When I repeated the phrase “your house” in Chinese—which I learned from a woman I met at the place I was staying—the old man finally took me to his house.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.