Series Vague Focal Space at the Window

Junzo Yoshimura, Sonoda House:

Sliding Glass Door Leading to the Garden and Waist-high Window Making a Space Somewhat Core to the Design

30 Mar 2022

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Japan

A room with a vague focal space

During an exhibition of the work of YOSHIMURA Junzo (1908–1997) in 2005 (held at The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts), YOSHIMURA was featured in NHK’s art program. His various works were introduced, which centered on mountain villas in Karuizawa. The former SONODA house was featured first in the program; in this house, the fireplace attracted my interest together with YOSHIMURA’s famous saying, “A good house is the one with something of a vague focal space, or a center of spatial gravity.” The concept of “vague focal space” was emphasized as the house was introduced. Thus, the question becomes: what is a “vague focal space”? To focus on this kind of space, let me now consider a space near the window, which is a main theme in this article.

-

Exterior seen from the approach.

The house’s four windows

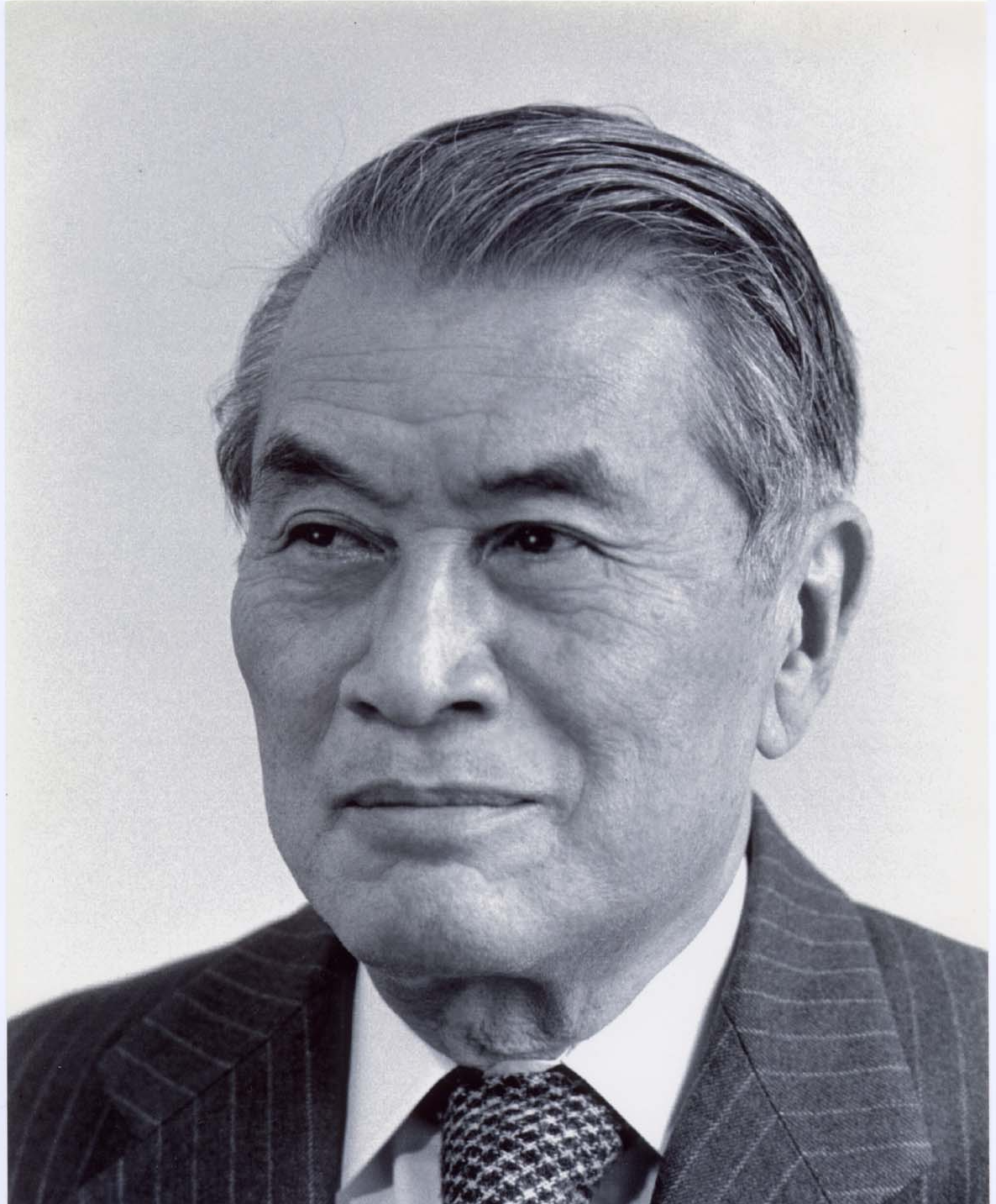

The house was designed for a world-famous pianist, SONODA Takahiro (1928–2004), and his wife Haruko, and was completed in 1955. Recently, it has attracted much attention as an example of the succession of a modernist house, for which the next owner was found after many concerts had been held.

The site is in a gentle residential area of Jiyugaoka, Tokyo. It is located along a slope and the site is surrounded by tall retaining walls, on top of which there is greenery, mainly consisting of large camphor trees. The building is barely visible between the bushes and the entrance gate is just up the slope. After opening the gate, turning right onto the slightly wide porch, and going up six steps, the architecture suddenly appears in front of you. The walls are finished with channel rustic siding in dark brown (originally oil-stained) and there is a porch entrance, which is under the deep eaves, that is reduced in height. Its scale creates a feeling of being in a small and cozy space. The façade is continuous, an effect of the deep greenery of the site. Above the eaves, one sees a gently sloping gable roof and white plaster gable walls, which are as low as the mezzanine floor.

-

Exterior seen from the garden.

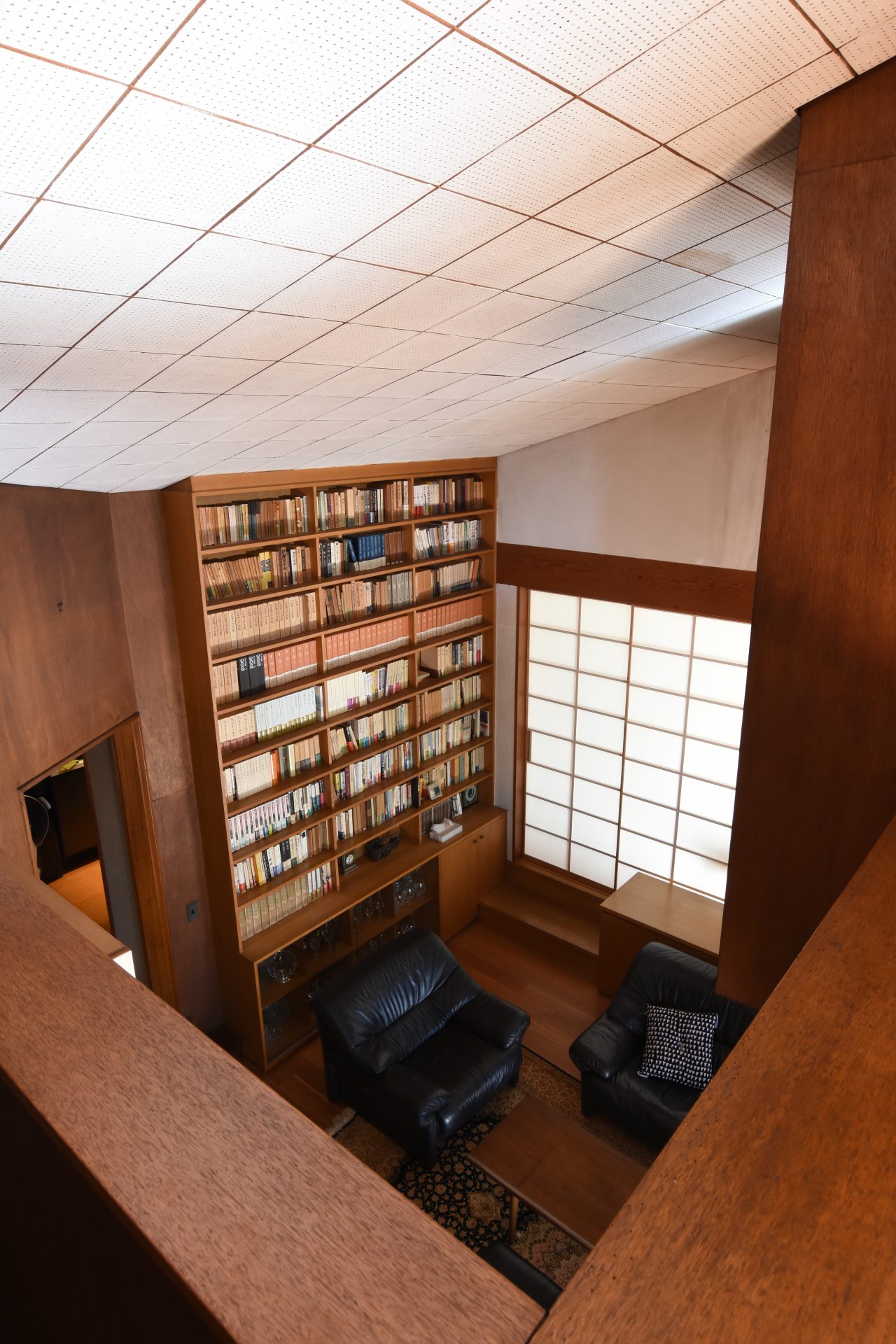

When you go through the entrance, you will see a kitchen on the left, a piano and the living room in front of you, and stairs to the right. Going up two steps takes you to a landing, where there is a bathroom door. Only nine more steps will bring you to the second floor. After passing through a corner that overlooks a music room on the first floor, there is a bedroom and a study.

The largest room in the house is the piano and living room, which constitute 43 m2 of the house’s total 73 m2. The room’s northern part has a double-height ceiling and used to have a tall vertical window (No. 1) before the house was extended and reconstructed by OGAWA Hiroshi, a disciple of YOSHIMURA. The room’s southern half has a low ceiling under the bedroom and a study upstairs. There is also a waist-high window (No. 2) to the east, a set of sliding glass doors (No. 3) to the southeast, and a waist-high corner window (No. 4) on the southwest side.

-

Piano and living room.

-

Double-height ceiling.

Vibrant planning

Two grand pianos were originally installed in the piano and living room. YOSHIMURA once said, “An architect will be full-fledged if they get a chance to design a house with a grand piano, a fireplace, and a TV.” YOSHIMURA married a violinist but, apparently, he experienced difficulty in planning the SONODA house. According to the plan, the house is so small that there is barely space around the pianos for living one’s daily life. After much effort, YOSHIMURA deemed it necessary to plan against the architectural grid. He designed the stairs to be at an angle and set the pianos diagonally against the grid. The desk and fireplace were also designed to be on the diagonal. YOSHIMURA also once said, “I think architecture should be on the grid. […] I put it on a grid. If it’s a grid itself, it’s just grid paper, but when a part of the grid is deformed, something in the architecture becomes vivid.” This is the kind of thinking that relates to windows.

-

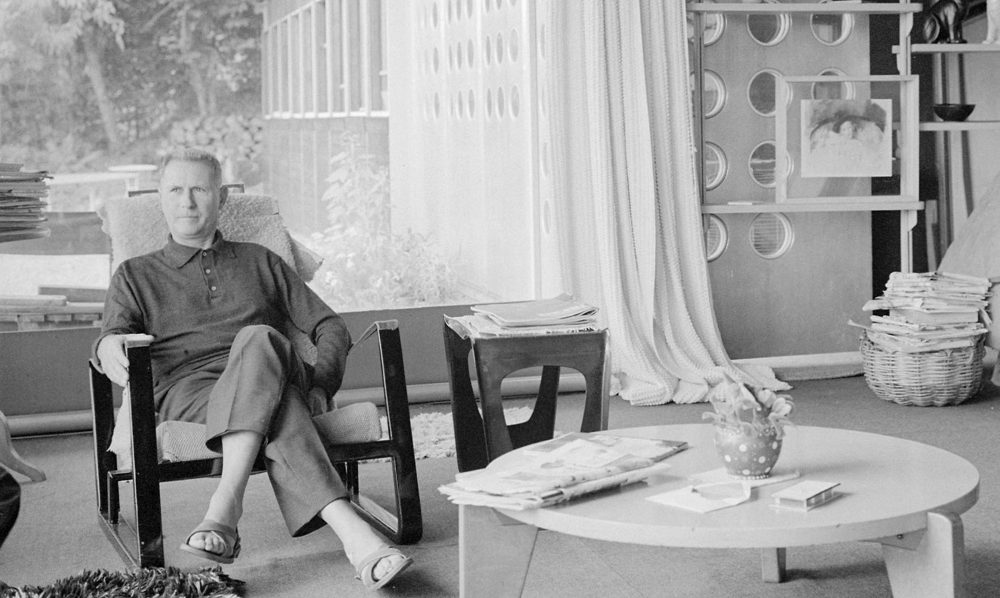

Two grand pianos and SONODA Takahiro. Courtesy of Heritage Houses Trust.

Details about the windows

Now let me explore the house’s four windows. First, there used to be a rectangular window (No. 1) behind the grand pianos. The double-height space does not correspond to the axis of the gable roof, whose ridge runs north to south. The height of the northern end is 3,480 mm and the height of the center is as high as 4,300. The windows were designed to be from the floor to the ceiling of the atrium, with an internal width of 1,060 mm. The window on the first floor slid open and shut, and the one on the second floor was fixed. Both windows were divided by girders, and both were attached to paper sliding doors that divided into three parts horizontally. This window illuminated the pianist diagonally from behind. It seems to have played a role of illuminating the musical scores. This window would have been the one closest to the performer.

Second, on the east side of the living room, there used to be a shelf for music scores, which extended against the south wall and bent diagonally onto the desk. Furthermore, this desk was provided with sunlight diagonally from the waist-high window (No. 2) on the left (the east side). The window’s lower frame was 760 mm from the floor; thus, its height just aligns with that of the desk. The window’s height was 910 mm and served as a desk light.

Third, looking next to the second window, there is a set of wooden sliding glass doors (No. 3) facing south toward the veranda. The wooden doors and paper sliding doors can be moved into the wall and the inside height is 1,970 mm. Just above the doors, there is a joist ceiling, and the space below the joist is 2,100 mm high. The joists and the diagonally placed base plate continue to the soffit area of the veranda, and there are two built-in louver lighting fixtures, one inside and one outside. The room and veranda seamlessly continue without any difference in their levels. The glass doors invite a pianist to sit at the piano, facing diagonally in relation to the room, leading to the garden.

-

Waist-high corner window and a set of sliding glass doors.

The last window is placed into the living room with a vague focal space. The space consists of a sofa, a waist-high corner window (No. 4), a fireplace, and pillars positioned outside to receive light from the southwest. The bottom of the window is set at 760 mm up from the floor, the same as the waist-high window on the east side (No. 2). However, this window’s inside height is 1,210 mm, which aligns with the adjacent glass door. The corner of the glass door on the west side meets the one on the south side. The frame of the south door is attached with a key and is wider than that of the west door. The width of the outer crosspiece of the paper sliding door is exactly the same as the depth of the crosspiece of the counterpart door. The proportion of the members is not the so-called YOSHIMURA’s proportion for neat details. (He usually designed the width of the outer crosspiece to be the same size as the other inner member, unlike the conventional proportion.)

There is a backrest under the window that doubles as storage space and the sofa can be pulled out to turn into a bed. Its color is mustard yellow and the height of the seat’s surface is as low as 360 mm. Notably, it also resembles Hans Wegener’s daybed. When you lie down and look up, you can see how the joists are hidden in the ceiling, which is finished with white plaster as wide as the depth of the sofa’s size. Viewed at a distance, this space is especially bright, and something of a 3D focal space filled with light appears here. A low table and two chairs sit in front of the sofa, and an angled fireplace rests against a bare concrete wall, facing both the sofa and chair.

A sofa built against a window

In Japan, it seems that designing the sofa to be built on the back of the window was common after FUJII Koji and other architects adopted it in 1920. As such, there should be earlier examples outside of Japan. The sofa originated from settee cushions placed on the back of a camel; sofas with armrests, similar to today’s sofas, first appeared in France in the eighteenth century. As a topic, the sofa is too broad to cover sufficiently here, so I will focus instead on the sofa’s origins in YOSHIMURA’s houses. YOSHIMURA had worked for Antonin Raymond (1888–1976) since his school days. Raymond was an architect who came to Japan with Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), who had a fondness for furnished sofas with windows in the background, to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1923). YOSHIMURA said that the Imperial Hotel inspired him to become an architect.

-

Details about the sofa.

Now, regarding the usage of sofas, I will take Fallingwater (1935) as an example. The house has three sofas in the living room on the first floor. The ceiling above the window where each sofa is located is quite low, at 2,160 mm. The windows extend fully, from the waist-high wall to the ceiling, and the ceiling is subdued and bright, nicely contrasting with the dark random stones on the floor. The ceiling above the sofa and the floor leading to the terrace are connected to the outside. Around thick stone pillars, shelves and desks are placed along the grid, making vague focal spaces separately and differently. YOSHIMURA once said to his wife Haruko, “If this house [the former SONODA house] was twice as big on all scales, it would be a wonderful house.” However, that would not have led to the designs in which a part of the plan was not set against the grid, and it would have instead created a different set of relationships between the windows and various other spaces. There is something about the house that feels like it is in Wright’s lineage, yet it is partly its narrowness that makes the house unique.

-

Fallingwater living room interior.

Focal space because of its tininess

In the piano and living room, various spaces corresponding to the windows have been created as a focal space, triggered by the partially-off-the-grid plan. This may be because the SONODA family had to live around two grand pianos in such a tiny space. However, because of the house’s narrowness, the philosophy of the relationship between the window and the focal space become apparent. YOSHIMURA’s notion is especially evoked by the corner windows on the southwest with their adjacent equipment, the fireplace as a core icon, and the three-dimensional lighted space. It is no wonder that a space composed of these elements was introduced as a representative example of a vague focal space.

One winter day, I went to see the house. Seeing the corner window with its paper sliding door, I remembered the words from an architect who had been YOSHIMURA’s disciple: “Here comes the afternoon sun to play with space.” Light comes to play by the window as a vague focal space.

YOSHIMURA Junzo (1908–1997)

YOSHIMURA was born in Tokyo in 1908. After graduating from the Department of Architecture of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Present: Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts) in 1931, he joined the Raymond Architectural Design Office and established the YOSHIMURA Junzo Design Office in 1941. He became an assistant professor in 1941, followed by becoming a professor, and then honorary professor at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. He designed office buildings and museums in addition to family and vacation homes. YOSHIMURA designed the SONODA house in collaboration with his colleague, the cellist Hiroshi Ozawa, when YOSHIMURA was an assistant professor at Tokyo School of Fine Arts.

Photo by MONMA Kaneaki