Talk Event Report: Swiss Window Journeys

Speakers: Momoyo Kaijima, Chie Konno, Fumiko Takahama, Mio Tsuneyama

22 JUN, 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Switzerland

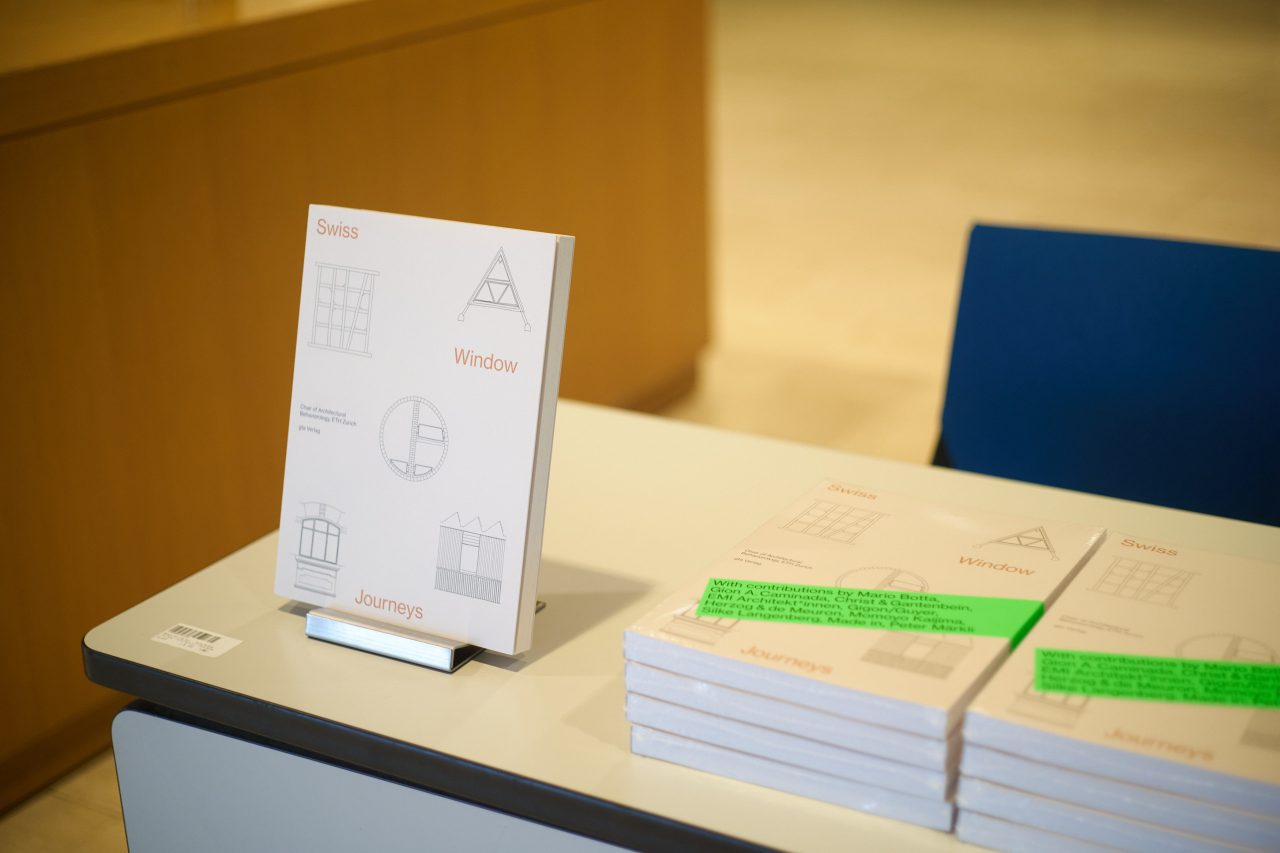

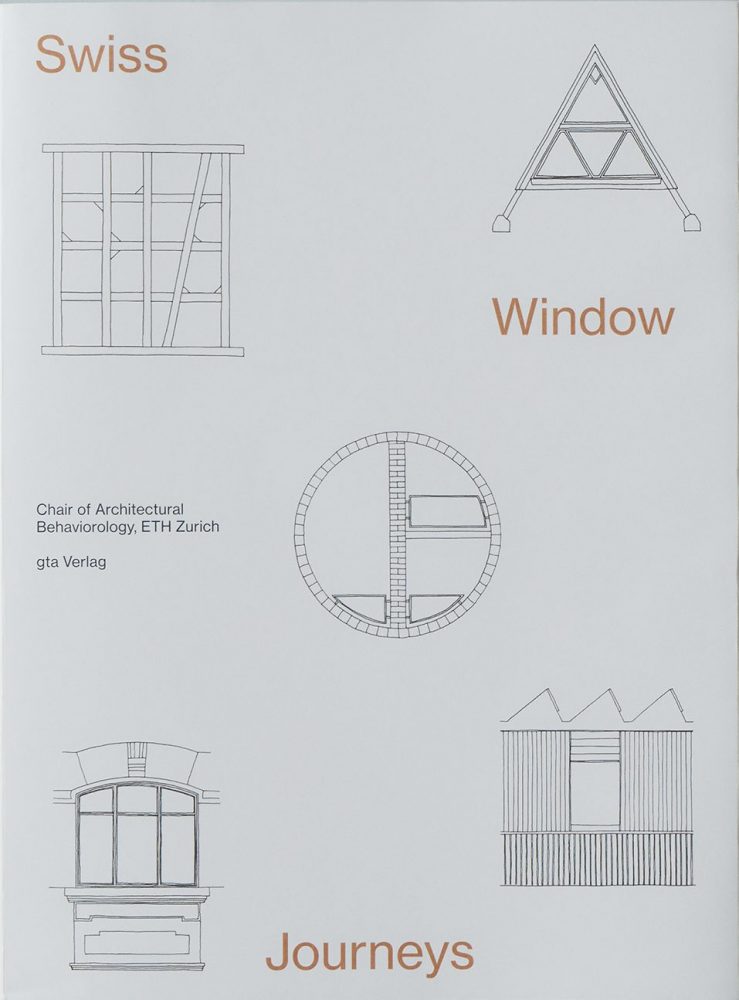

On June 22, 2024 (Saturday), the Swiss Window Journeys – Swiss Windows and Architecture talk event was held in the Architectural Hall of the Architectural Institute of Japan. The event was held to celebrate the publication of Swiss Window Journeys Architectural Field Notes, a survey of Swiss windows by Professor Momoyo Kaijima of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ), and was organized by the Window Research Institute and the Japan Swiss Architectural Association.

Swiss Window Journeys Architectural Field Notes, a collection of window drawings and commentaries collected through fieldwork, interviews with Swiss architects, and other products of six years of efforts involving Swiss windows and architecture, was specially sold at the venue. It is also worth noting that the event made daycare services available to guests.

Distance from Local Resources as Seen By Architectural Behaviorology

The event began with a lecture by Ms. Kaijima. As co-chair of Atelier Bow-Wow, she has continued to pursue the concept of “architectural behaviorology,” teaching a course on the subject at ETHZ since her arrival there in 2017.

In her talk, she spoke about coming to hold a broad perspective that goes beyond architecture around the time she was involved in supporting the reconstruction of the Oshika Peninsula in Ishinomaki following the Great East Japan Earthquake, visiting locations such as farming and fishing villages more often and taking into account local resources and industry. When she considered how to depict them in a truthful way, she felt that hand-drawn illustrations are effective in providing a deep understanding because of the way they output an embodiment of what is seen, which is to say information.

-

Momoyo Kaijima

“Modernization now causes local resources to grow more distant from oneself, while our information society causes us to exceed the resources we hold in reality. I developed an interest in how to correct this problem while asking students to think about what can be done through architecture.”

Kaijima spoke about creating a book on architectural behaviorology while considering how societies can archive and use the cultural expression and technology that is the window, as well as the resource and shared asset that is knowledge. She continues to think about how we can approach, share, and store resources, as well as our distance to them, while also keeping in mind the inescapable reality that architecture is built on solid ground.

Swiss Windows

She next discussed the difference between European and Japanese windows through examples she designed as part of Atelier Bow-Wow while giving thoughts based on her fieldwork in Switzerland. Kaijima positioned the European window, a term containing the word “wind,” as an aperture dug into a wall that is designed to cut out a piece of the scenery. In comparison, there are a variety of ways to write “window” in Japanese, including as an opening and closing between pillars, and she identified this as part of a major difference in the understanding of windows in Switzerland and Japan.

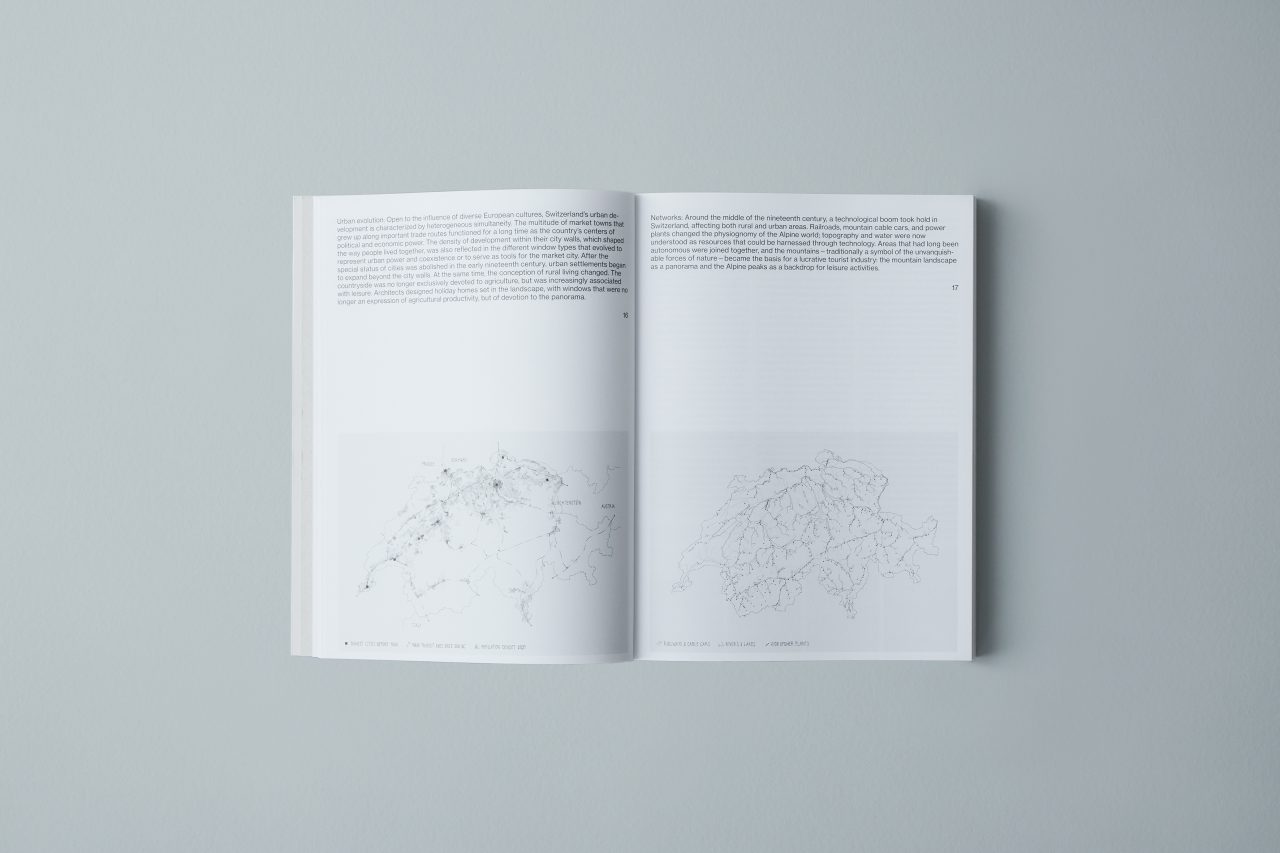

The placement of the Alps in the center of Switzerland geographically and culturally divides the country, and it is surrounded by nations including France, Germany, Austria, and Italy. It is extremely dry, and strong architecture is required in order to help its people live in its mountain climate with powerful sunlight in the summer. Trees cannot survive beyond 1,500 meters of elevation on its solid rock mountains, making it an area where lumber is not easily available, and it is also notable for its industries linked to hydroelectric plants powered by mountain drainage as well as accompanying transportation networks.

She ended by saying she hoped to speak in the following discussion on how, as a country actively addressing climate issues, Switzerland is moving away from using old windows and about the resulting concerns regarding a loss of culture.

Window Design and Locality

The second half of the event consisted of a discussion between four architects with experience living in Switzerland, with Ms. Kaijima joined by Fumiko Takahama and Mio Tsuneyama on the panel as Chie Konno moderated.

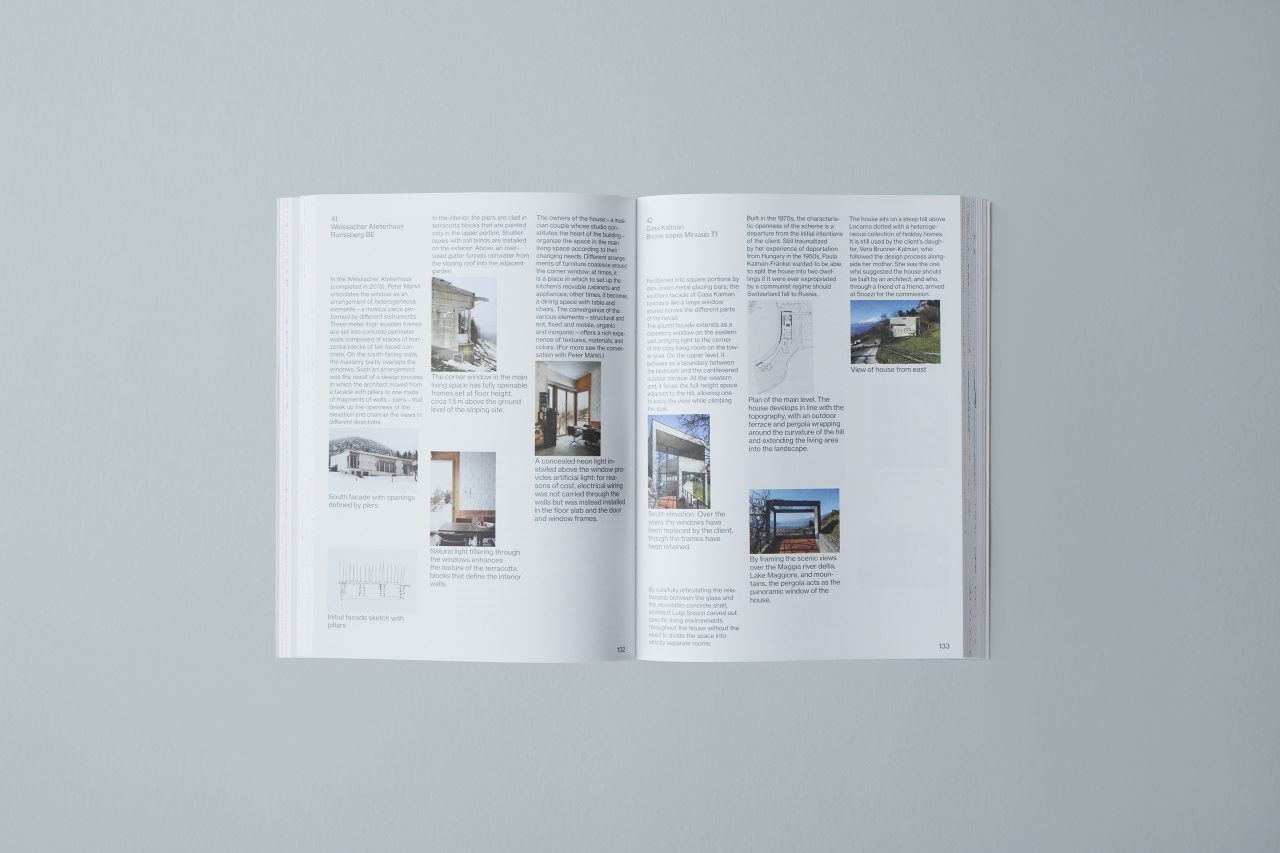

The discussion was preceded by a presentation by Ms. Takahama on her experience in Switzerland and her own designs. After internships and study in Zurich, Ms.Takahama worked at Herzog & de Meuron (H&deM) in Basel for five years before returning to Japan and set up her own design firm. She reminisced about windows in Switzerland, where double-sash windows were the standard, introducing photos of the windows in the flat she lived at in Basel.

She also introduced recent works such as the NODEA Gallery, a showroom for NODEA, a high end brand of windows and doors, that carries electric sash windows “Sky-Frame” from Switzerland’s that H&deM adopted in some projects.

-

Fumiko Takahama

Next, Ms. Tsuneyama presented insights on windows she gained during her two stays in Switzerland. She said that the country has a law that allows building owners to demand the preservation of views from their windows.

She also described her surprise at how commonplace it was when drafting facades to shade windows in order to create a sense of depth based on the placement of insulation and heat-blocking materials. She oversaw a studio at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) from 2022-2023, carrying out a case study on the typology of food and housing. Grapes for white wine are grown on the south slope of Lake Geneva, and it is dotted with urban, high-density communities. There she realized there are still unique homes with their backs to the landscape and openings on the road-facing side in order to increase sunlight and output, as well as small windows on the first floor in order to ventilate gasses produced by fermenting wine.

Ms. Tsuneyama returned from Switzerland in 2012, around the time when potsu-mado (punched windows) were in vogue and discussions were being held about how to move beyond them. She pointed out how the design of windows has changed, saying that now it seems to have become a time when facades can be created by zoning with different levels of insulation.

-

Mio Tsuneyama

Having heard the presentations so far, Ms. Konno asked about the relationship between window-making industries in Switzerland and designers, given that while Swiss windows express depth as they incorporate complex elements such as materials and mechanisms for movement, it seems difficult in Japan to create the windows one wants due to cost, artisan skill, and systems.

Ms. Kaijima responded by saying, “There are close to no prefabricated windows, and so each one has to be created. Mockups of facades are created on construction sites and examined before a larger structure is created. For example, when renovating a building, there is often a need to switch to double-paned glass (to meet current regulations), and resulting changes in window weight need to be addressed one by one. (While there are no prefabricated items), companies each have their own patented technologies and methods, and working with architects often involves the development of new windows. So while there may be risks, they also see the potential.”

Ms. Takahama pointed out differences in façade design, including windows, by saying, “After returning from Switzerland, where windows normally are custom-made, I experienced culture shock in Japan, as architects are assumed to memorize all the sizes of prefabricated windows. Window itself is considered as a part of design in Switzerland, and in big projects at H&deM there were teams only focused on facades. Also production of the windows were not restricted domestic. I heard they brought not only materials for Miu Miu Aoyama (which they built), but even artisans.”

Ms. Tsuneyama speculated, “In Switzerland, inexpensive Danish prefabricated products were often used in thin frames, but given the many renovation projects in Switzerland, perhaps standardized sizes wouldn’t be of much use.”

-

Chie Konno

This was followed by Ms. Konno stating that it seems “very difficult to clear systematic and regulatory hurdles in Japan,” to which Ms. Kaijima replied, “While the laws change quite a bit between Switzerland’s various regions, the initial challenge is explaining to local officials and residents about what will be built and learning where it is acceptable to place windows. Not receiving opposition from neighbors, including regarding setbacks, is extremely important. As for the law, wooden homes are not the leading type in Switzerland, and so fire prevention standards may be different.” She also continued, “Right now in Switzerland, advanced barns are required for livestock (due to the spread of the concept of animal welfare), leading to a glut of older barns. The presence of one of those barns can place a tract into an agricultural zone, so the hurdle to placing windows on a barn in order to make it into a house is high.”

This satisfied Ms. Konno, who said, “While the difficulty of getting permission from locals and finding a way to preserve local culture isn’t a frequent issue in Japan, it makes me think that must be a major factor in the Swiss landscape being maintained.”

The Characteristics of the City

Ms. Konno also asked the group about the relationship between typology and locality, and each of the panelists gave their thoughts based on their experiences.

“Switzerland has four different cultural areas. Towns look completely different in each of them, and there are different educational bases as well. I’m currently studying detached houses, and when you look into their designers it seems as though they’re influenced by the cultural area where they were educated.” (Kaijima)

“I thought back to Switzerland’s diversity, with both contemporary architecture and traditional architecture. I always found myself referring to nothing but contemporary architecture when I lived there, but looking at this book I found it interesting that traditional architecture such as barns, which blended in with nature and were seen in total as scenery, became foregrounded.” (Takahama)

“Lausanne has many buildings made of sandstone, and I think of it as a round town with corners that are easy to smooth out. Meanwhile, Bern is a town made of hard rock. It made me think that geological differences are linked to how a town expresses itself.” (Tsuneyama)

-

The discussion taking place

After the discussion, there was a question from the audience about design that makes use of wall thickness (window depth) resulting from thicker insulation over the last 20 years or so.

“Annette Gigon said that making thick walls means less rentable space, and so developers tend to want to use glass panes rather than build walls. There is more discussion in Switzerland as a whole now about how to use as few fossil fuels as possible, and once when I was judging for a prize, I saw for the first time a wall with no insulation, instead using a multi-layered wood panel that was about 40 centimeters thick. The issue of wall thickness may change if materials change, but there is more and more that is formed without emitting CO2. The Swiss sense that the cost of walls is more expensive than windows when the two are compared is different from Japan. They are very free when it comes to how to make windows, and there are more new ways of making walls such as simply setting walls while giving windows an organic feeling. I think this may bring about more flexible uses of windows. ” (Kaijima)

This was followed by questions by Kentaro Ishida, Board Director of the Japan Swiss Architectural Association (an organizer of this event) and Fuminori Nousaku of the Architectural Institute of Japan’s Voice of Earth Design Subcommittee (a supporter of the event) about Swiss design education as well as window design and global warming. Switzerland, which founded ETH in order to increase its national strength, now faces a need to increase its density as it approaches a population of over 10 million, and the event ended with a comment made possible by the hybrid experiences of design in Japan and education in Switzerland that this does not seem realistic without changing Swiss living spaces that provide an average of 46 square meters per person, as well as lifestyles and systems.

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at Switzerland’s Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba from 2009 to 2022, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), Columbia University (2017), and Yale University (2023). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city, the suburbs, and agricultural, mountain, and fishing villages through publications such as Made in Tokyo, Pet Architecture, and Commonalities. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia. In 2022, she was awarded the Wolf Prize for Architecture.

Chie Konno

Chie Konno was born in Kanagawa, Japan in 1981. After graduating from the Tokyo Institute of Technology with a B.E. in architecture in 2005, she attended the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich from 2005-2006 as a scholarship student. She received a Ph.D. from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in engineering in 2011. After founding KONNO in 2011, she became the head of teco in 2015. Konno was made Specially Appointed Associate Professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology in 2021. She is involved in the architectural design of houses, welfare facilities, public facilities, and more as well as urban development and art installations, working to create spaces across various structures and systems. Her major works include the Sunny Loggia House (awarded the 2012 Tokyo Society of Architects & Building Engineers Residential Architecture Gold Prize, the 2014 Architectural Institute of Japan Award for New Designer of the Year, and more), the Care Hall for Child, Elderly and Dining mixed facility for elder and child care (awarded the SD Review 2016 Kajima Prize), the Japan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2016 (awarded a Special Mention), and the Kasugadai Center Center cultural base for local coexistence (awarded the 2023 AIJ Prize and more). Her major written works include Windowscape: Window Behaviorology (2010, Film Art Inc., co-authored).

Fumiko Takahama

Fumiko Takahama was born in 1979. After graduating from Kyoto University in 2003, she began graduate school at The University of Tokyo and studied abroad at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, worked as an intern at Christian Keretz and HHF Architects before completing the Master’s program in 2007. She worked at Herzog & de Meuron from 2007 to 2012. In 2012, she established +ft+ / Fumiko Takahama Architects and was an Academic Researcher at Kobe University. From 2013 to 2015, she was a Research Associate at The University of Tokyo. In 2017, she became a Part-time Lecturer at Kogakuin University, and in 2023 she became a Part-time Lecturer at the Shibaura Institute of Technology. Her major works include Giant House in Oiso, Maebashi Brick Warehouse, and the JINS Holdings Tokyo Head Office. She is the co-author of Kaigai de kenchiku o shigoto ni suru (Gakujutsu Shuppansha).

Mio Tsuneyama

Mio Tsuneyama was born in Kanagawa in 1983. In 2005, she graduated from the Tokyo University of Science, then served as an intern at Bonhôte Zapata Architectes in Switzerland from 2005 to 2006. From 2006 to 2008, she received a scholarship from the Swiss government and completed the program at École Polytechnique Fédéral de Lausanne (EPFL) in 2008. Tsuneyama worked at HHF Architects from 2008 to 2012, then founded Studio mnm in 2012. She was an Assistant Professor at Tokyo University of Science from 2015 to 2020, and a Special Lecturer at the school from 2020 to 2021. Tsuneyama was a Visiting Professor at EPFL from 2022 to 2023, and an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia University in 2023. Her major works include Holes in the House and Fudomae House (Tokyo), Piles and Pointed Roof (Tokyo), Himi Migrant Village (Toyama), and House on Classical Elements (Akiya Smart House Building E) (Kanagawa). Major awards she has received include the 2015 Residential Architecture Prize from the Tokyo Society of Architects & Building Engineers, as well as a Special Mention at the 2016 Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibition for the Japan Pavilion. She co-authored Urban Wild Ecology (2024, TOTO Publishing) with Fuminori Nousaku.

Event Details for Swiss Window Journeys – Swiss Windows and Architecture

Date and time: June 22, 2024 (Saturday), 15:00-16:30 (doors open at 14:30)

Location: Architectural Hall of the Architectural Institute of Japan, (5-26-20 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8414, JAPAN)

Speaker: Momoyo Kaijima (Architect, Professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich)

Guests: Chie Konno (Architect), Fumiko Takahama (Architect), Mio Tsuneyama (Architect)

Hosted by: Window Research Institute, Japan-Switzerland Architectural Culture Association

Supported by: Embassy of Switzerland in Japan

Cooperation: Architectural Institute of Japan, Voice of Earth Design Subcommittee, Shinkenchiku-sha Co., Ltd.