Series Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 1: Windows Visited by Spirits: Pingdong

14 Sep 2021

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

After his experience on a journey through villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries, Ryuki Taguma now lives in Yilan, located in northeast Taiwan, while practicing architectural design. In this series, Taguma will pursue the many faces of Taiwan as it exists today as seen through windows.

It has been five years since I started living in Taiwan.

Contemporary Taiwan is, for the most part, a country where you can live a pleasant life. While many of its toilets cannot flush paper, it is not difficult to gather all the items needed for day-to-day living. While you may have some doubts about how hygienic some of its food is, it is cheap and delicious. While its countless signs seem to be on the verge of imminent collapse, you feel safe walking around at night. You can live here in a way not too different from life in Japan so long as you aren’t high-strung, and so I have times when I nearly forget I’m in a foreign country. That said, its foreignness does show its face to me at unexpected moments.

Chinese New Year in Taiwan is one example, when strange red pieces of paper are stuck to the windows of homes. These are like talismans, and appear to be meant to prevent spirits from entering inside. The iron grills placed over windows in Taiwan, a vestige of a time of worse public safety, may be an unfamiliar sight to a Japanese person, but these red pieces of paper seem to be meant for a spiritual kind of defense. Though they are placed there year-round, the custom is to replace them all at once when the new year comes, making the red highlights around windows particularly noticeable during this time of year.

-

Red pieces of paper placed on windows

The most important time of the year in Taiwan is chūn jié, or Chinese New Year. Based on the lunar calendar, Chinese New Year’s Day falls on a different date between late January and early February each year. People reserve high speed rail tickets far in advance once the day starts approaching, as everyone returns to their hometown at the same time. As an aside, many Taiwanese people enjoy returning to their family’s home in general, not just during the New Year. They’ll do so on a moment’s notice to spend time with their family if they have free time on the weekend. One of the many things I learned after coming to Taiwan is that its people have stronger ties to their family as compared to the Japanese. Though this must be aided by the ease of returning home, given that the country is only about the size of Japan’s island of Kyushu, I have to wonder if we would return home as frequently even if Japan as a whole was the same size. I can’t help but feel the influence of Confucian thought in this.

With nothing in particular to do over the most recent Chinese New Year, I decided to spend a few days at a friend’s home in Pingdong, Taiwan’s southernmost county, and experience a Taiwanese New Year’s there. The home belonged to a Hakka family. The Hakka are one of the people of Taiwan (comprising about 20 percent of its population), and seem to be a Han Chinese subgroup who can also be found in southeast China and Southeast Asia. Though I may understand Chinese, I couldn’t make out a word of the Hakka conversations taking place at my friend’s family home. My friend’s grandparents also spoke to me in Japanese, making conversation that much more complicated. I will put the topic of Taiwan’s ethnic diversity aside for another day, though, as I would like to introduce here their custom of replacing those red pieces of paper during chūn jié.

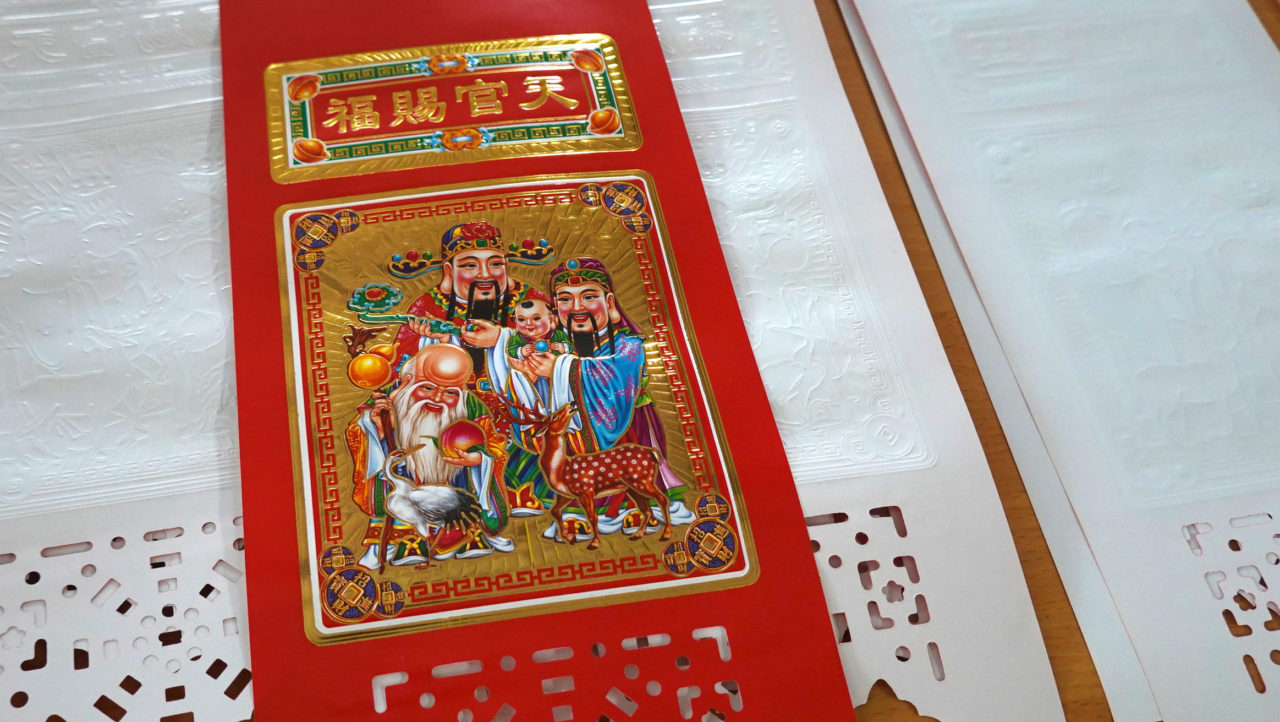

“We’re going to buy chūn lián.”

I was taken outside as I ate my breakfast. Chūn lián is the name for these red pieces of paper, and my friend and I had been appointed to assist with their replacement. Booths selling chūn lián had popped up around the temple. Auspicious words were written on the red pieces of paper of all sizes, and some were adorned with illustrations of Taoist icons such as a man with a long beard, as well as a plump baby. Everyone was buying an incredible number of them. If this many are guaranteed to sell once a year, the market for chūn lián seems quite secure going forward. Though some still do seem to be handwritten, most were printed, mass-produced items. I bought one for myself as a keepsake. On it are the auspicious characters 天官賜福, “heavenly official’s blessing,” as well as an embossed old man, baby, and more printed on a gold background, yet it only cost me about 50 yen. This low price tells you everything you need to know about the massive scale at which these are consumed.

-

People buying chūn lián.

-

Newly purchased chūn lián. It feels full of auspicious elements.

Once we returned to my friend’s house, next was the job of affixing our just-bought chūn lián. We placed them over the gates, doors, windows, and everything you could call an opening inside the house. We even ended up placing one on the electric meter, but the idea of “spirits” entering from there did strike me as a little amusing. According to my friend, the “spirit” I’ve been referring to is formally a lion-like man-eating monster known as a nián shòu. Windows take one slip, while larger openings take more, either three or five. We first removed the chūn lián affixed last year (which are already starting to fade), then used glue to place a new one on in the same location. It reminded me of the annual act of re-papering shoji doors.

-

My friend’s home. A red slip of paper is placed over everything you could call an opening, as if to seal something off.

-

An electric meter box can be seen on the left. Spirits can even come from there.

-

Five slips go on large gates.

Having placed this many chūn lián around the home, I did feel concerned that spirits may all rush in from the few openings we didn’t place them on, but my friend told me there was no need to place them on the second-floor windows that were out of reach. Was he sure about that? Taiwan’s laid-back culture can manifest itself in these ways.

Though the Japanese tradition of decorating the entrance of one’s home with pine and bamboo decorations during the New Year is somewhat similar to this, the Japanese tradition is meant to be an invitation for “good gods,” while chūn lián adopt the opposite mindset of keeping “spirits (bad gods)” out. Perhaps Japan has a stronger emphasis on keeping fortune close while Taiwan emphasizes keeping evil out. In other words, this could mean that Taiwan sees windows as a place where bad things can enter. Though windows around the world now look similar due to the spread the aluminum sash, we may be able to get a glimpse of deep-rooted feelings towards windows that still remain in Taiwan and China through these kinds of actions surrounding them. When I think this, my mind leaps to the idea that this feeling may also be related to their windows’ inset iron grills.

-

A line of red sheets of paper at a Taoist temple.

-

Fittings, iron grills, and chūn lián. Taiwan’s windows are heavily defended.

In the afternoon, we paid a New Year’s visit to a nearby Taoist temple. When I saw chūn lián affixed to every opening to the rooms where its gods were entempled, just as we’d just done at my friend’s home, I felt a sense of familiarity in spite of being at a temple in a foreign country. That said, given all the defenses, whether fittings, iron grills, or chūn lián, windows in Taiwan seem like a difficult business.

(Continued in issue 2)

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda University’s Nakatani Norihito Lab with his master’s in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window“). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Culture’s overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda University’s Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. During his time off from graduate school, he traveled around villages and folk houses in 11 Asian and Middle Eastern countries (his essays about this trip are serialized on the Window Research Institute website as “Travelling Asia through a Window”). In 2017, he began working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects in Yilan County, Taiwan. In 2018 he was accepted to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Culture’s overseas training program, and in 2019 he was accepted to the artist overseas training program promoted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. He is based in Yilan, where it rains for the majority of the year, from which he designs various public buildings such as parks, cultural facilities, parking structures, bus terminals, and more.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 14: A Window for Standing Still—Fieldoffice Architects, Paomagudao Park

22 Jan 2025

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 13: Democracy Under Canopies (Fieldoffice Architects)

18 Nov 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 12: A Small Church for the Indigenous (Taitung)

20 Jun 2024

Contemporary Taiwan through a Window

Issue 11: Joined Somewhere, Connected Throughout—Chen Chi-Kwan, Tunghai University Methodist Hall

04 Mar 2024